Exploring the Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy in the Relationship Between Caregiver Contribution and Resilience in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

Background

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Setting and Sampling

2.3. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Instruments

2.5. Caregiver Self-Efficacy

2.6. Caregiver Contribution to Self-Care

2.7. Resilience Index

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Sample Size Estimation

2.9. Ethical Consideration

3. Results

3.1. General Description

3.2. Contribution to Self-Care and Resilience

3.3. Factors Associated with Resiliency

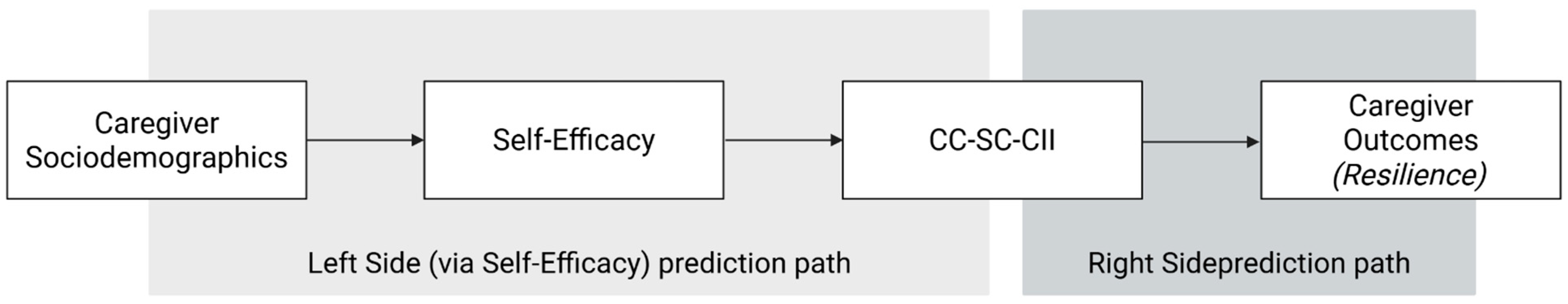

3.3.1. Model 1: Left Side

3.3.2. Model 2: Right-Side

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Clinical and Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IBD | Inflammatory Bowel Disease |

| CD | Crohn’s Disease |

| UC | Ulcerative Colitis |

| CC-SC-CII | Caregiver Contribution to Self-Care of Chronic Illness Inventory |

| CD-RISC-25 | Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale—25 items |

| CSE-CSC | Contributing to Patient Self-Care Scale |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| SE | Standard Error |

| STROBE | Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

References

- Artom, M., Czuber-Dochan, W., Sturt, J., Proudfoot, H., Roberts, D., & Norton, C. (2019). Cognitive-behavioural therapy for the management of inflammatory bowel disease-fatigue: A feasibility randomised controlled trial. Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 5, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balbinot, P., Pellicano, R., & Testino, G. (2023). Burden of caregiving of alcohol related liver disease patients: A possible role of training and caregiver groups frequency. Proposal of a method, preliminary results. Minerva Gastroenterology, 69(4), 486–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control (pp. ix, 604). W H Freeman/Times Books/Henry Holt & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Bray, J., Fernandes, A., Nguyen, G. C., Otley, A. R., Heatherington, J., Stretton, J., Bollegala, N., & Benchimol, E. I. (2016). The challenges of living with inflammatory bowel disease: Summary of a summit on patient and healthcare provider perspectives. Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 2016(1), 9430942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, E.-M., Chen, L.-S., Li, Y.-T., & Chen, C.-T. (2023). Associations between self-management behaviors and psychological resilience in patients with COPD. Respiratory Care, 68(4), 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., Geng, J., Wang, J., Wu, Z., Fu, T., Sun, Y., Chen, X., Wang, X., & Hesketh, T. (2022). Associations between inflammatory bowel disease, social isolation, and mortality: Evidence from a longitudinal cohort study. Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology, 15, 17562848221127474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M. L., Pressler, S. J., Dunbar, S. B., Lennie, T. A., & Moser, D. K. (2010). Predictors of depressive symptoms in caregivers of patients with heart failure. The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 25(5), 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, N. M., Gong, M., & Kaciroti, N. (2014). A model of self-regulation for control of chronic disease. Health Education & Behavior: The Official Publication of the Society for Public Health Education, 41(5), 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, K. M., & Davidson, J. R. T. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18(2), 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Maria, M., Ausili, D., Lorini, S., Vellone, E., Riegel, B., & Matarese, M. (2022). Patient self-care and caregiver contribution to patient self-care of chronic conditions: What is dyadic and what it is not. Value in Health: The Journal of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research, 25(7), 1165–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maria, M., Iovino, P., Lorini, S., Ausili, D., Matarese, M., & Vellone, E. (2021). Development and psychometric testing of the caregiver self-efficacy in contributing to patient self-care scale. Value in Health: The Journal of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research, 24(10), 1407–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A., & Palazzeschi, L. (2012). Connor-davidson resilience scale: Proprietà psicometriche della versione italiana. Counseling, 5, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Dionne-Odom, J. N., Azuero, A., Taylor, R. A., Wells, R. D., Hendricks, B. A., Bechthold, A. C., Reed, R. D., Harrell, E. R., Dosse, C. K., Engler, S., McKie, P., Ejem, D., Bakitas, M. A., & Rosenberg, A. R. (2021). Resilience, preparedness, and distress among family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 29(11), 6913–6920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Onofrio, A. M., Balzoni, L. M., Ferrajoli, G. F., DI Vincenzo, F., Napolitano, D., Schiavoni, E., Kotzalidis, G. D., Simonetti, A., Mazza, M., Rosa, I., Pettorruso, M., Sani, G., Gasbarrini, A., Scaldaferri, F., & Camardese, G. (2025). Monitoring the psychopathological profile of inflammatory bowel disease patients treated with biological agents: A pilot study. Minerva Gastroenterology, 71(1), 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, N., Deng, H., Fu, T., Zhang, Z., Long, X., Wang, X., & Tian, L. (2022). Association between caregiver ability and quality of life for people with inflammatory bowel disease: The mediation effect of positive feelings of caregivers. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 988150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrarese, D., Vecchione, M., Spagnolo, G., Mirijello, A., Di Vincenzo, F., Belella, D., Camardese, G., D’Onofrio, A. M., Mora, V., Napolitano, D., Cammarota, G., Scaldaferri, F., Chieffo, D. P. R., Gasbarrini, A., Dionisi, T., & Addolorato, G. (2025). The role of resilience in mitigating depression and anxiety in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 196, 112309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorino, G., Caprioli, F. A., Onali, S., Macaluso, F. S., Bezzio, C., Armelao, F., Armuzzi, A., Baldoni, M., Bodini, G., Castiglione, F., Daperno, M., Festa, S., Furfaro, F., Gionchetti, P., Leone, S., Luglio, G., Milla, M., Mocci, G., Napolitano, D., … Fantini, M. C. (2025). Adaptation of the European Crohn’s Colitis Organisation quality of care standards to Italy: The Italian group for the study of inflammatory bowel disease consensus. Digestive and Liver Disease: Official Journal of the Italian Society of Gastroenterology and the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver, 57, 1135–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelman, A., Carlin, J. B., Stern, H. S., Dunson, D. B., Vehtari, A., & Rubin, D. B. (2013). Bayesian data analysis (3rd ed.). Chapman and Hall/CRC. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graff, L. A., Walker, J. R., & Bernstein, C. N. (2009). Depression and anxiety in inflammatory bowel disease: A review of comorbidity and management. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, 15(7), 1105–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grano, C., Lucidi, F., & Violani, C. (2017). The relationship between caregiving self-efficacy and depressive symptoms in family caregivers of patients with Alzheimer disease: A longitudinal study. International Psychogeriatrics, 29(7), 1095–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtmann, J., Koch, T., Lochner, K., & Eid, M. (2016). A comparison of ML, WLSMV, and Bayesian methods for multilevel structural equation models in small samples: A simulation study. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 51(5), 661–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, G. G., & Windsor, J. W. (2021). The four epidemiological stages in the global evolution of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature Reviews. Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 18(1), 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, K., Dibley, L., Chauhan, U., Greveson, K., Jäghult, S., Ashton, K., Buckton, S., Duncan, J., Hartmann, P., Ipenburg, N., Moortgat, L., Theeuwen, R., Verwey, M., Younge, L., Sturm, A., & Bager, P. (2018). Second N-ECCO consensus statements on the European nursing roles in caring for patients with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis. Journal of Crohn’s & Colitis, 12(7), 760–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, S. R., Graff, L. A., Wilding, H., Hewitt, C., Keefer, L., & Mikocka-Walus, A. (2018). Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analyses—Part I. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, 24(4), 742–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luszczynska, A., Scholz, U., & Schwarzer, R. (2005). The general self-efficacy scale: Multicultural validation studies. The Journal of Psychology, 139(5), 439–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGilton, K. S., Vellani, S., Yeung, L., Chishtie, J., Commisso, E., Ploeg, J., Andrew, M. K., Ayala, A. P., Gray, M., Morgan, D., Chow, A. F., Parrott, E., Stephens, D., Hale, L., Keatings, M., Walker, J., Wodchis, W. P., Dubé, V., McElhaney, J., & Puts, M. (2018). Identifying and understanding the health and social care needs of older adults with multiple chronic conditions and their caregivers: A scoping review. BMC Geriatrics, 18(1), 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, K., Glassner, A., Norman, R., James, D., Sculley, R., LealVasquez, L., Hepburn, K., Lui, J., & White, C. (2022). Caregiver self-efficacy improves following complex care training: Results from the learning skills together pilot study. Geriatric Nursing, 45, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, L., Wang, K., Yao, J., Ma, J., Chen, Y.-W., Zeng, Q., & Liu, K. (2024). Clinical characteristics and treatment of middle-aged and elderly patients with IBD in Shanghai, China. International Journal of General Medicine, 17, 6053–6064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, T. A., & Dimatteo, M. R. (2013). Importance of family/social support and impact on adherence to diabetic therapy. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Therapy, 6, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napolitano, D., Biagioli, V., Bartoli, D., Cilluffo, S., Martella, P., Monaci, A., Vellone, E., & Cocchieri, A. (2025). Validity and Reliability of the Self-Care of Chronic Illness Inventory in Patients Living With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 34(11), 4642–4653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napolitano, D., Vellone, E., Iovino, P., Scaldaferri, F., & Cocchieri, A. (2024). Self-care in patients affected by inflammatory bowel disease and caregiver contribution to self-care (IBD-SELF): A protocol for a longitudinal observational study. BMJ Open Gastroenterology, 11(1), e001510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northouse, L. L., Katapodi, M. C., Song, L., Zhang, L., & Mood, D. W. (2010). Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: Meta-analysis of randomized trials. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 60(5), 317–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacio G, C., Krikorian, A., Gómez-Romero, M. J., & Limonero, J. T. (2020). Resilience in caregivers: A systematic review. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine®, 37(8), 648–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajput, I. B., Khan, D., Mirza, R., Ahmed, N., Shah, S. U., Asad, M., Gibaud, S., & Shah, K. U. (2025). Inflammatory bowel disease: Exploring pathogenesis, epidemiology, conventional therapies, and advanced nanoparticle based drug delivery systems. BioNanoScience, 15(1), 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegel, B., Jaarsma, T., & Strömberg, A. (2012). A middle-range theory of self-care of chronic illness. ANS. Advances in Nursing Science, 35(3), 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiavoni, E., Greco, D., Scaldaferri, F., & Napolitano, D. (2025). Exploring the competencies of inflammatory bowel disease nurses in Italy: A cross-sectional survey. Annals of Gastroenterology, 38(4), 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, K. L., Stewart, B. J., Archbold, P. G., Caparro, M., Mutale, F., & Agrawal, S. (2008). Effects of caregiving demand, mutuality, and preparedness on family caregiver outcomes during cancer treatment. Oncology Nursing Forum, 35(1), 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebern, M., & Riegel, B. (2009). Contributions of supportive relationships to heart failure self-care. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 8(2), 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, R., Thakur, E., Bradford, A., & Hou, J. K. (2018). Caregiver burden in adults with inflammatory bowel disease. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology: The Official Clinical Practice Journal of the American Gastroenterological Association, 16(1), 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szanton, S. L., & Gill, J. M. (2010). Facilitating resilience using a society-to-cells framework: A theory of nursing essentials applied to research and practice. ANS. Advances in Nursing Science, 33(4), 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szanton, S. L., Han, H.-R., Campbell, J., Reynolds, N., Dennison-Himmelfarb, C. R., Perrin, N., & Davidson, P. M. (2020). Shifting paradigms to build resilience among patients and families experiencing multiple chronic conditions. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(19–20), 3591–3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S. E., & Stanton, A. L. (2007). Coping resources, coping processes, and mental health. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 377–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Textor, J., Hardt, J., & Knüppel, S. (2011). DAGitty: A graphical tool for analyzing causal diagrams. Epidemiology, 22(5), 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellone, E., Barbaranelli, C., Pucciarelli, G., Zeffiro, V., Alvaro, R., & Riegel, B. (2020a). Validity and reliability of the caregiver contribution to self-care of heart failure index version 2. The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 35(3), 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellone, E., Biagioli, V., Durante, A., Buck, H. G., Iovino, P., Tomietto, M., Colaceci, S., Alvaro, R., & Petruzzo, A. (2020b). The influence of caregiver preparedness on caregiver contributions to self-care in heart failure and the mediating role of caregiver confidence. The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 35(3), 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vellone, E., Riegel, B., & Alvaro, R. (2019). A situation-specific theory of caregiver contributions to heart failure self-care. The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 34(2), 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitaliano, P. P., Zhang, J., & Scanlan, J. M. (2003). Is caregiving hazardous to one’s physical health? A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 129(6), 946–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Elm, E., Altman, D. G., Egger, M., Pocock, S. J., Gøtzsche, P. C., Vandenbroucke, J. P., & STROBE Initiative. (2014). The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. International Journal of Surgery, 12(12), 1495–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, L., Wang, S., Wang, Y., Zhu, L., Wang, T., Yu, X., Dong, J., & Guan, Y. (2024). Factors promoting and hindering resilience in youth with inflammatory bowel disease: A descriptive qualitative study. Nursing Open, 11(4), e2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, M., Hossein-Javaheri, N., Hoxha, T., Mallouk, C., & Tandon, P. (2024). Work productivity impairment in persons with inflammatory bowel diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis, 18(9), 1486–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D. S.-F., De Maria, M., Barbaranelli, C., Vellone, E., Matarese, M., Ausili, D., Rejane, R.-S. E., Osokpo, O. H., & Riegel, B. (2021). Cross-cultural applicability of the self-care self-efficacy scale in a multi-national study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 77(2), 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y., Wang, H., Song, X., Tan, W., Liu, Y., Liu, H., Hu, C., & Guo, H. (2025). Exploring the multidimensional impact of caregiver burden in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Frontiers in Public Health, 13, 1528778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zand, A., Kim, B. J., van Deen, W. K., Stokes, Z., Platt, A., O’Hara, S., Khong, H., & Hommes, D. W. (2020). The effects of inflammatory bowel disease on caregivers: Significant burden and loss of productivity. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1), 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | CD (n = 131, 48.4%) | UC (n = 144, 51.6%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age Me [IQR] | 50 [40.5–59] | 53.5 [44–60] |

| Gender n (%) | ||

| Female | 76 (58%) | 84 (58.3%) |

| Male | 55 (42%) | 60 (41.7%) |

| Care Load n (%) | ||

| Mild | 54 (41.2%) | 49 (34%) |

| Moderate | 60 (45.8%) | 76 (52.8%) |

| Severe | 17 (13%) | 18 (12.5%) |

| Educational Level n (%) | ||

| Bachelors | 29 (22.1%) | 44 (30.6%) |

| High School | 66 (50.4%) | 68 (47.2%) |

| Middle School | 33 (25.2%) | 28 (19.4%) |

| Primary School | 3 (2.3%) | 4 (2.8%) |

| Work Status n (%) | ||

| Homemaker | 15 (11.5%) | 14 (9.7%) |

| Retired | 21 (16%) | 25 (17.4%) |

| Student | 6 (4.6%) | 2 (1.4%) |

| Unemployed | 6 (4.6%) | 2 (1.4%) |

| Worker | 83 (63.4%) | 101 (70.1%) |

| Relationship n (%) | ||

| Partner/Spouse | 63 (48.1%) | 84 (58.3%) |

| Family (Parent/Sibling) | 26 (19.8%) | 24 (16.7%) |

| Other Family | 12 (9.2%) | 14 (9.7%) |

| Friend | 18 (13.7%) | 11 (7.6%) |

| No relationship specified | 12 (9.2%) | 11 (7.6%) |

| Patients Time from diagnosis (y) M(SD) | 11.2 (9.96) | 11.5 (8.74) |

| Patients Disease Activity n (%) | ||

| Remission | 98 (74.8%) | 51 (35.4%) |

| Mild | 14 (10.7%) | 24 (16.7%) |

| Moderate | 12 (9.2%) | 34 (23.6%) |

| Severe | 7 (5.3%) | 35 (24.3%) |

| Time in Charge n (%) | ||

| <1 Year | 29 (22.1%) | 35 (24.3%) |

| 1–3 Year | 21 (16%) | 29 (20.1%) |

| 3–5 Years | 18 (13.7%) | 22 (15.3%) |

| >5 Years | 63 (48.1%) | 58 (40.3%) |

| Resilience Domains | Entire Sample (n = 275) | CD (n = 131) | UC (n = 144) | p-Value § |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spiritual Influences | 8 [6–10] | 8 [6–10] | 8 [6–10] | 0.214 |

| Personal Competence | 15 [13–18.5] | 16 [14–19] | 15 [13–18] | 0.110 |

| Acceptance of Change | 15 [13–18] | 16 [13–18] | 15 [13–17.2] | 0.143 |

| Trust in one’s intuition | 21 [18–24] | 21 [18–24] | 21 [17–24] | 0.162 |

| Life Control | 15 [12–18] | 15 [13–18] | 15 [12–17] | 0.138 |

| Resiliency (Total Score) | 74 [65–84] | 76 [65.5–85] | 72 [64–83] | 0.083 |

| Pathway | CC-SC-CII Maintenance | CC-SC-CII Monitoring | CC-SC-CII Management |

|---|---|---|---|

| Β [IC95%] | Β [IC95%] | Β [IC95%] | |

| Indirect Effects (via Self-Efficacy) | |||

| Disease Activity → CSE-CSC → CC-SC-CII | 0.002 [−0.155, 0.351] | 0.009 [−0.596, 1.184] | 0.010 [−0.479, 0.941] |

| Educational Level → CSE-CSC → CC-SC-CII | −0.001 [−0.769, 0.668] | −0.003 [−2.611, 2.477] | −0.004 [−2.104, 1.952] |

| Occupational Status → CSE-CSC → CC-SC-CII | 0.003 [−0.446, 0.932] | 0.012 [−1.656, 3.286] | 0.013 [−1.190, 2.822] |

| Direct Effects | |||

| CSE-CSC → CC-SC-CII | 0.069 [−0.069, 0.264] | 0.266 [0.277, 0.712] | 0.299 [0.244, 0.571] |

| Disease Activity → CC-SC-CII | 0.034 [−1.134, 2.206] | 0.034 [−1.134, 2.206] | 0.034 [−1.134, 2.206] |

| Educational Level → CC-SC-CII | −0.013 [−5.175, 4.344] | −0.013 [−5.175, 4.344] | −0.013 [−5.175, 4.344] |

| Occupational Status → CC-SC-CII | 0.044 [−3.056, 6.288] | 0.044 [−3.056, 6.288] | 0.044 [−3.056, 6.288] |

| Predictors | Personal Competence β [IC95%] | Trust β [IC95%] | Life Control β [IC95%] | Change Acceptance β [IC95%] | Spiritual Influence β [IC95%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC-SC-CII Maintenance | 0.138 [0.001, 0.037] | 0.063 [−0.011, 0.033] | 0.106 [−0.003, 0.030] | 0.037 [−0.010, 0.020] | 0.011 [−0.013, 0.015] |

| CC-SC-CII Monitoring | −0.029 [−0.019, 0.013] | 0.029 [−0.017, 0.024] | −0.043 [−0.019, 0.010] | 0.015 [−0.013, 0.016] | 0.069 [−0.007, 0.019] |

| CC-SC-CII Management | 0.117 [−0.001, 0.037] | 0.170 [0.008, 0.061] | 0.161 [0.004, 0.044] | 0.221 [0.014, 0.049] | 0.176 [0.006, 0.035] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bozzetti, M.; Marcomini, I.; Lo Cascio, A.; Magurano, M.R.; Ribaudi, E.; Petralito, M.; Milani, I.; Amato, S.; Orgiana, N.; Parello, S.; et al. Exploring the Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy in the Relationship Between Caregiver Contribution and Resilience in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1381. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101381

Bozzetti M, Marcomini I, Lo Cascio A, Magurano MR, Ribaudi E, Petralito M, Milani I, Amato S, Orgiana N, Parello S, et al. Exploring the Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy in the Relationship Between Caregiver Contribution and Resilience in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1381. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101381

Chicago/Turabian StyleBozzetti, Mattia, Ilaria Marcomini, Alessio Lo Cascio, Maria Rosaria Magurano, Eleonora Ribaudi, Monica Petralito, Ilaria Milani, Simone Amato, Nicoletta Orgiana, Simone Parello, and et al. 2025. "Exploring the Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy in the Relationship Between Caregiver Contribution and Resilience in Inflammatory Bowel Disease" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 10: 1381. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101381

APA StyleBozzetti, M., Marcomini, I., Lo Cascio, A., Magurano, M. R., Ribaudi, E., Petralito, M., Milani, I., Amato, S., Orgiana, N., Parello, S., Puca, P., Scaldaferri, F., Mazza, M., Marano, G., & Napolitano, D. (2025). Exploring the Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy in the Relationship Between Caregiver Contribution and Resilience in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Behavioral Sciences, 15(10), 1381. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101381