1. Introduction

1.1. Self-Stigma and Negative Coping Strategies

Individuals or groups who possess certain socially undesirable or disreputable traits, which lower their status in society, become stigmatized and experience a reduced self-perceived value. Stigma refers to the degrading and insulting labels society assigns to these individuals or groups (

Franks et al., 2024).

Goffman (

1963) formally introduced the concept of “stigma” in Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Stigma research mainly refers to the reactions of the general public toward stigmatized groups. Self-stigmatization is the response of stigmatized individuals or groups, directing the stigmatizing attitudes inwardly (

Patrick et al., 2005). Public stigmatization is an important source of self-stigmatization, and when individuals internalize the stigmatizing views of the public, it leads to reduced self-esteem, impaired self-efficacy, and behaviors such as withdrawal, including social avoidance (

Bharti et al., 2024). Research shows that stigmatization and perceived threats significantly predict psychological distress and behavioral vigilance (

Franks et al., 2024). Individuals who are stigmatized often experience persistent anxiety and depressive states (

Szepietowska et al., 2024) and may exhibit antisocial behaviors due to negative inducement (

Ge, 2024). Self-stigma includes cognitive, emotional, and behavioral components and may lead to negative emotions such as fear, loneliness, anxiety, and depression, thereby negatively impacting mental health (

Lipai, 2020;

S. Pan et al., 2023). This is especially true for individuals with depression-prone traits, as self-stigmatization reduces their self-esteem levels (

Lasalvia et al., 2025). Previous studies have focused on migrant populations, the LGBTQ+ community, and people with disabilities. However, research is limited on self-stigmatization in groups facing stigma during public health crises, such as individuals infected during the early COVID-19 quarantine.

From a theoretical standpoint, this study adopts a psychological perspective while explicitly acknowledging the broader epidemiological context. Although the primary mechanisms under investigation are cognitive and affective, individual-level responses to stigma are embedded within societal and public health processes. Integrating psychological insights with a population-level understanding allows us to examine coping strategies as both individual and socially consequential behaviors, thereby bridging micro- and macro-level analyses (

Link & Phelan, 2001;

Parker & Aggleton, 2003).

Coping strategies refer to cognitive and behavioral ways individuals manage difficulties and can be categorized as positive or negative. Negative coping strategies involve emotional tactics such as avoidance and denial, which individuals use to reduce discomfort from frustration or stress (

Zou et al., 2024). Individuals adopting negative coping tend to engage in self-defensive behaviors, often relying on the alleviation of negative emotions like feelings of deprivation (

L. Pan et al., 2024). Empirical studies have confirmed the impact of negative coping: for example, among high school students, negative coping predicted guilt (

Le & Jin, 2024); among medical students, negative coping correlated positively with mental health problems (

Dai et al., 2023) and mediated the relationship between psychological capital and academic burnout (

Liu et al., 2025) or workplace bullying and quiet quitting (

Galanis et al., 2024). Studies on perceived discrimination have also linked it to negative coping among immigrants in Spain (

Gabarrell-Pascuet et al., 2023) and Latino HIV-positive individuals (

Barreras et al., 2023). Taken together, self-stigmatization may influence coping choices in stressful contexts through similar mechanisms.

Therefore, this study seeks to examine cognitive and affective mechanisms through which self-stigma motivates the use of negative coping strategies, focusing on individuals infected during the early stages of quarantine.

1.2. The Mediating Role of Negative Emotions

Self-stigmatization may induce negative emotions, which in turn promote negative coping strategies. Self-stigmatization is closely related to negative emotional experiences (

Savickas & Porfeli, 2012;

Liang & Huang, 2025), and risk events like the COVID-19 pandemic can also trigger negative emotions. Research shows negative emotions predict negative coping strategies (

J. Hao et al., 2023), exacerbate rumination (

Shao et al., 2025), impair cognitive function (

Kircher, 2024), and influence social decision-making (

Xie et al., 2024).

Taken together, these findings suggest that negative emotions may serve as one pathway linking self-stigmatization to negative coping strategies. From an epistemic perspective, modeling negative emotions as mediators enables the integration of individual psychological processes with population-level outcomes. By considering how internalized stigma translates into affective responses that may influence behavioral patterns during public health crises, the study situates psychological mechanisms within an epidemiologically relevant framework (

Friedli & World Health Organization, 2009). In the present study, negative emotions are modeled as a parallel mediator, operating simultaneously with inspirational motivation rather than sequentially.

1.3. The Mediating Role of Inspirational Motivation

External support factors, such as inspirational motivation from organizational or community leaders, may buffer the negative effects of self-stigmatization. Inspirational motivation refers to behaviors that enhance intrinsic motivation by clarifying common goals and future prospects (

Joshi et al., 2009). Research indicates inspirational motivation improves mental health (

Ward, 2024), organizational commitment (

Rauf, 2024), and positive expectations during crises (

de Sousa, 2023), while reducing negative outcomes such as turnover intentions (

Clark, 2025). Given that self-stigmatization is associated with lower treatment-seeking, higher discontinuation, and worse symptoms (

Lee et al., 2016), inspirational motivation may serve as an independent pathway mitigating the impact of self-stigmatization on negative coping.

This conceptualization highlights the interplay between individual psychological processes and socio-structural supports, reflecting a multi-level epistemic approach that integrates psychological theory with applied public health interventions. It emphasizes how leadership and community-level motivational strategies can buffer the negative consequences of self-stigma during epidemiological crises.

1.4. Overview and Hypotheses

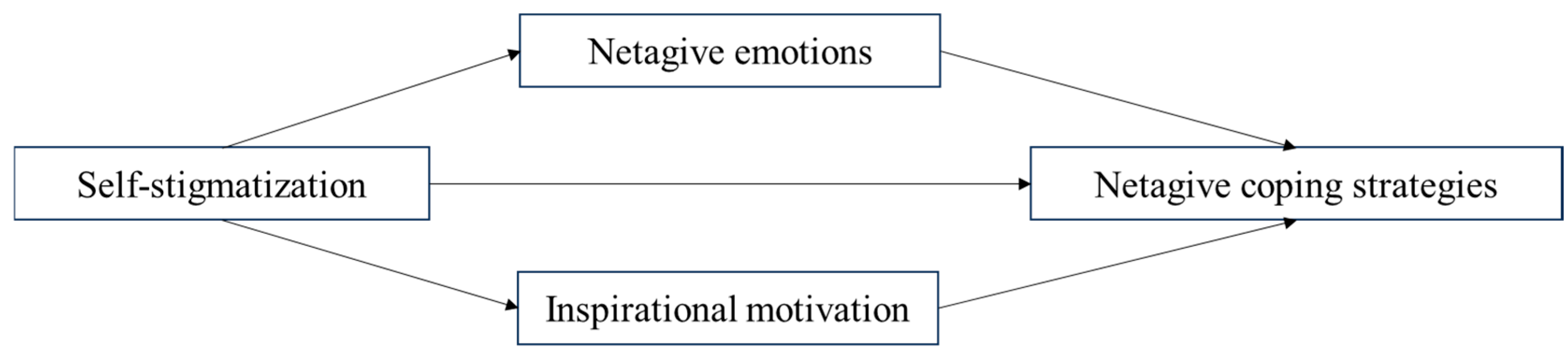

In this study, we investigate how self-stigmatization among individuals in quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic predicts negative coping strategies, with two potential mediators: negative emotions and inspirational motivation. Although sequential mediation can be considered in some contexts, the present study adopts a parallel mediation model, in which negative emotions and inspirational motivation are treated as simultaneous mediators with two independent indirect pathways. This approach is appropriate because (1) theoretical and empirical evidence suggests that negative emotions and inspirational motivation operate independently rather than in a fixed causal sequence (

Savickas & Porfeli, 2012;

Joshi et al., 2009;

Ward, 2024), and (2) parallel mediation allows clearer estimation of the unique indirect effects of each mediator while controlling for the other, avoiding over-interpretation of causal order that is not supported by data.

The mediators are estimated using Hayes’ PROCESS macro (version 3.3) with Model 4, which implements a nonparametric Bootstrap procedure (5000 resamples) to compute bias-corrected confidence intervals for each indirect effect. This method is widely recommended for testing mediation because it does not assume normality of the indirect effect distribution and provides robust estimation of effect sizes (

Hayes, 2013;

Preacher & Hayes, 2004).

Based on the literature, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1: During the outbreak of the pandemic, self-stigmatization among individuals in quarantine areas significantly predicts their negative coping strategies.

H2: Negative emotions mediate the relationship between self-stigmatization and negative coping strategies among individuals in quarantine areas.

H3: Inspirational motivation mediates the relationship between self-stigmatization and negative coping strategies among individuals in quarantine areas.

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual parallel mediation model tested in this study, with self-stigmatization as the independent variable, negative coping strategies as the dependent variable, and negative emotions and inspirational motivation as simultaneous mediators.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The participants in this survey consisted of 147 individuals living in high-incidence epidemic areas (including both isolated and non-isolated zones) and those within infectious disease hospitals. Participants were residents of mainland China, recruited from multiple provinces and municipalities, including Hubei, Zhejiang, Xinjiang, Shanghai, Shandong, Guangdong, Jiangxi, Shaanxi, Jiangsu, Hebei, Beijing, Henan, Gansu, and Anhui. Among the participants, 70 were male, accounting for 47.6% of the sample, and 77 were female, accounting for 52.4%. The participants were categorized into age groups: 31 individuals were under 20 years old, accounting for 21.1% of the sample; 26 were aged 20–29, accounting for 17.7%; 41 were aged 30–39, accounting for 27.9%; 29 were aged 40–49, accounting for 19.7%; 15 were aged 50–59, accounting for 10.2%; and 5 were over 60 years old, accounting for 3.4%. In terms of education, 5 participants had middle school or lower education, accounting for 3.4%; 18 had a high school level of education (including vocational and technical schools), accounting for 12.2%; 17 had a college diploma, accounting for 11.6%; 55 had a bachelor’s degree, accounting for 35.4%; and 52 held a master’s degree or higher, also accounting for 35.4%.

For comparing variables between individuals in the quarantine area and those in non-quarantine areas, 145 samples were randomly selected from the non-quarantine zone. Of these, 55 were male, accounting for 37.9%, and 90 were female, accounting for 62.1%. The participants were divided into age groups: 27 were under 20 years old, accounting for 18.6%; 44 were aged 20–29, accounting for 30.3%; 34 were aged 30–39, accounting for 23.4%; 26 were aged 40–49, accounting for 17.9%; 13 were aged 50–59, accounting for 9%; and 1 was over 60 years old, accounting for 0.7%. In terms of education, 15 participants had middle school or lower education, accounting for 10.3%; 29 had a high school level of education (including vocational and technical schools), accounting for 20%; 33 had a college diploma, accounting for 22.8%; 55 had a bachelor’s degree, accounting for 37.9%; and 13 held a master’s degree or higher, accounting for 9%. The non-quarantine zone participants were randomly selected from a pool of 1071 individuals for comparative analysis with those in quarantine zones.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Stigmatization Scale

The Stigmatization Scale was adapted from the Devaluation–Discrimination Scale (PDDS) developed by

Link et al. (

1989) to measure public stigmatization in the context of COVID-19. The scale consists of 12 items and uses a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“Strongly disagree”) to 5 (“Strongly agree”), with higher scores indicating greater perceived public stigmatization. A sample item is: “Most people don’t mind making close friends with those who have had COVID-19.” Items that are positively worded (i.e., agreement reflects lower stigmatization) were reverse-scored prior to analysis. Composite scores were calculated by summing all 12 items, yielding possible total scores ranging from 12 to 60. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for the 12 items in this study was 0.93.

2.2.2. Negative Emotions Scale

The Negative Emotions Scale (DASS-21) (

Moussa et al., 2001) consists of 21 items, including three dimensions: depression, anxiety, and stress, with seven items for each dimension. A four-point Likert scale is used, ranging from 1 (“Does not apply”) to 4 (“Always applies”), with higher scores indicating more severe negative emotions. One sample item is: “I found it hard to wind down.” Composite scores were calculated by summing all 21 items, yielding possible scores ranging from 21 to 84. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for the 21 items in this study was 0.97.

2.2.3. Negative Coping Strategies Scale

The Negative Coping Strategies Scale is based on the negative behavior subscale of the Coping Strategies Scale developed by

Shi et al. (

2003). The scale consists of three items and uses a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“Never”) to 5 (“Always”), with higher scores indicating more negative coping strategies. One sample item is: “Tried to see the positive side of the situation (positive); let my feelings out somehow (negative).” Composite scores were calculated by summing the three items, yielding possible scores ranging from 3 to 15. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for the three items in this study was 0.72.

2.2.4. Inspirational Motivation Subscale

The Inspirational Motivation Subscale is based on the vision motivation dimension of the Transformational Leadership Scale developed by

Li and Shi (

2005). The scale consists of six items, using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“Strongly Disagree”) to 5 (“Strongly Agree”), with higher scores indicating higher levels of inspirational motivation. One sample item is: “Paints a desirable future for everyone.” Composite scores were calculated by summing all six items, yielding possible scores ranging from 6 to 30. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for the six items in this study was 0.97.

2.3. Procedure

The survey was conducted nationwide through an online method. The questionnaire was designed and distributed via the Wen-Juan-Xing platform and disseminated to participants through social media platforms such as WeChat. In addition to open recruitment via social media, we coordinated with local community/neighborhood leaders and quarantine-area coordinators to notify residents about the study and facilitate participation. The instructions emphasized the confidentiality and authenticity of the responses. All participants provided informed consent prior to data collection. For individuals who did not regularly use social media or had difficulty completing the questionnaire online, trained personnel (e.g., community staff or designated survey assistants) provided guidance and assistance to complete the survey on-site or by phone, while still ensuring that informed consent procedures were followed. The research procedures complied with the ethical standards of the institution and the Declaration of Helsinki.

SPSS 21.0 software was used for reliability analysis, descriptive statistics, independent samples t-tests, and correlation analysis, while Hayes’ PROCESS macro (version 3.3) was employed to conduct the mediation effect testing. This macro applies a nonparametric Bootstrap resampling procedure (5000 iterations) to estimate the confidence intervals of indirect effects, which provides a robust test of mediation without relying on the normality assumption (

Hayes, 2013;

Preacher & Hayes, 2004). Harman’s single-factor test was conducted for data analysis, which revealed that there were six factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 before rotation. The variance explained by the first factor was 37.54%, which is below the 40% threshold. This suggests that the sample does not exhibit significant common method bias (

Zhou & Long, 2004).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis of Variables

Correlation analysis was conducted on the total scores of the four variables: self-stigmatization, negative emotions, negative coping strategies, and transformational leadership’s inspirational motivation. The results indicated that self-stigmatization was significantly positively correlated with negative emotions and negative coping strategies, and significantly negatively correlated with inspirational motivation. Negative emotions were significantly positively correlated with negative coping strategies but were not significantly correlated with inspirational motivation. Negative coping strategies were significantly negatively correlated with inspirational motivation (see

Table 1 for details).

3.2. Comparison of Differences in Variables Between Individuals in Quarantine Areas and Non-Quarantine Areas

A comparison of the categorical differences in the four variables revealed that individuals in quarantine areas had significantly higher levels of negative emotions compared to those in non-quarantine areas. Additionally, the inspirational motivation scores of individuals in quarantine areas were significantly lower than those of individuals in non-quarantine areas. No significant differences were found for the other two variables (

Table 2). The Bar Chart of

t-test Results is shown in

Figure 2.

3.3. Differences in Gender, Age, and Educational Attainment Among Participants in the Quarantine Area

Analyses of demographic variation revealed differential patterns across the four focal dimensions. Independent-samples t-tests indicated no significant gender differences between male (N = 70) and female (N = 77) participants on perceived stigma (t(145) = 0.60, p > 0.05, d = 0.10), negative affect (t(133.96) = −0.99, p > 0.05, d = −0.16), approach motivation (t(145) = −0.24, p > 0.05, d = −0.04), or avoidance motivation (t(134.71) = −1.86, p > 0.05, d = −0.31). One-way ANOVA across age groups showed a significant effect only for negative affect (F(5,141) = 2.565, p = 0.03); perceived stigma (p = 0.421), approach motivation (p = 0.662), and avoidance motivation (p = 0.096) did not differ significantly by age. With respect to educational attainment, ANOVA results revealed significant group differences for negative affect (F = 2.943, p = 0.023) and approach motivation (F = 5.044, p = 0.001), whereas perceived stigma (p = 0.346) and avoidance motivation (p = 0.093) showed no significant variation across education levels. Overall, demographic effects were most pronounced for negative affect and approach motivation, while perceived stigma and avoidance motivation remained largely invariant across the examined demographic strata.

3.4. The Relationship Between Self-Stigmatization and Negative Coping Strategies: Mediation Effect Testing

Controlling for gender, age, and educational attainment, we tested whether negative emotions mediate the relationship between self-stigmatization and negative coping strategies. Self-stigmatization significantly and positively predicted negative coping strategies (

β = 0.41,

t = 5.36,

p < 0.001) and also significantly and positively predicted negative emotions (

β = 0.44,

t = 5.87,

p < 0.001). In turn, negative emotions significantly and positively predicted negative coping strategies (

β = 0.37,

t = 4.63,

p < 0.001) (see

Table 3).

Bootstrapped mediation analysis with 5000 resamples indicated a significant indirect effect of self-stigmatization on negative coping strategies via negative emotions (indirect effect = 0.163; 95% CI [0.056, 0.305]), as the confidence interval does not include zero; this indirect effect accounted for 39.78% of the total effect. At the same time, the direct effect of self-stigmatization on negative coping strategies remained significant (direct effect = 0.247; 95% BootCI [0.089, 0.406]), indicating that negative emotions partially mediate the relationship between self-stigmatization and negative coping strategies (see

Table 4).

Controlling for gender, age, and educational attainment, we examined whether approach motivation mediates the relationship between self-stigmatization and negative coping strategies. Self-stigmatization significantly and positively predicted negative coping strategies (

β = 0.41,

t = 5.36,

p < 0.001), and it was a significant negative predictor of approach motivation (

β = −0.22,

t = −2.74,

p < 0.01). The path from approach motivation to negative coping strategies did not reach statistical significance (

β = −0.15,

t = −1.95,

p > 0.05). See

Table 5 for path coefficients.

Bootstrapped mediation analysis (5000 resamples) yielded a small but statistically significant indirect effect through approach motivation (indirect effect = 0.034; 95% CI [0.002, 0.090]), indicating a reliable mediation despite the non-significant direct path; this indirect effect accounted for 7.32% of the total effect. Concurrently, the direct effect of self-stigmatization on negative coping strategies remained significant (direct effect = 0.377; 95% CI [0.223, 0.531]) and represented 92.68% of the total effect. These findings indicate that approach motivation partially mediates the association between self-stigmatization and negative coping strategies, although the mediating contribution is modest. See

Table 6.

4. Discussion

First, individuals located in Quarantine Areas exhibited markedly different psychological profiles compared with those outside such zones. Independent-samples t-tests demonstrated that residents of Quarantine Areas reported significantly greater negative affect and significantly lower inspirational (approach) motivation. These findings are consistent with evidence that the COVID-19 pandemic engendered widespread psychological strain globally (

Torales et al., 2020;

Torous et al., 2020). Quarantine Areas, as geographically and socially delineated high-risk contexts, not only heighten objective threats to health but also concentrate negative information and social scrutiny, thereby intensifying negative emotional responses. Concurrently, the sustained demands of pandemic management appear to deplete psychological resources and diminish future-oriented optimism (i.e., inspirational motivation). Together, these patterns underscore the pronounced mental-health burden borne by residents of Quarantine Areas and the need for timely, targeted psychological support.

Second, self-stigmatization exerted a robust direct effect on negative coping strategies among residents of Quarantine Areas. In this study, self-stigmatization denotes the internalization of socially transmitted devaluation and discriminatory attitudes associated with COVID-19-related stereotypes, producing experiences of exclusion and adverse psychological consequences. As members of territorially marked high-risk groups, residents of Quarantine Areas are vulnerable to external stigmatizing processes that facilitate internalization. Our results show that self-stigmatization directly increases reliance on maladaptive coping (e.g., avoidance, self-blame), in line with prior empirical work on health-related stigma (

Mayrhuber et al., 2017). The stigmatization sequence—labeling, differential treatment, rejection, and societal exclusion—often culminates in individuals adopting negative self-views, reduced self-esteem, and diminished self-efficacy, which in turn promote passive acceptance and maladaptive responses to stress (

Thompson et al., 2013). This mechanism provides a parsimonious account of the direct pathway from internalized stigma to negative coping strategies.

Third, mediation analyses indicate that negative emotions and inspirational motivation operate as parallel mediators linking self-stigmatization to negative coping strategies, but they differ substantially in effect magnitude. Specifically, the pathway via exacerbated negative emotions accounted for the bulk of the indirect effect (≈39.25%), whereas the pathway via weakened inspirational motivation accounted for a comparatively modest share (≈7.83%). The dominant role of negative emotions is consistent with stigma internalization models and modified labeling theory, which posit that external demeaning evaluations become incorporated into the self-concept and precipitate pervasive negative affect (

Overstreet & Quinn, 2016). Internalized stigma undermines self-worth and fosters an attentional bias toward threat and loss-related information, thereby amplifying anxiety, depressive symptoms, and other forms of negative affect (

S. Hao & Zhang, 2025). Sustained negative affect also disrupts prospective cognition and goal-directed planning (

Guo et al., 2025), which reduces adaptive problem-solving and increases the likelihood of resorting to negative coping strategies when confronted with stressors.

Although the mediating contribution of inspirational motivation was smaller, it is theoretically meaningful. In our framework, inspirational motivation indexes an individual’s intrinsic, future-oriented drive and sense of purposeful expectation. Self-stigmatization undermines self-esteem and perceived competence, thereby eroding hope, agency, and goal pursuit. When individuals’ intrinsic motivational resources are weakened, they experience reduced perceived control and diminished expectation of successful outcomes, which lowers proactive coping and increases proneness to avoidance or resignation. This interpretation accords with psychological empowerment theory, which links perceived control and motivational resources to reduced passive coping (

Zhang & Bartol, 2010). Thus, while negative affect constitutes the principal psychological conduit through which self-stigmatization translates into maladaptive coping, loss of inspirational motivation represents an additional, though modest, pathway that further compromises individuals’ capacity to engage adaptively with stressors.

Collectively, these findings refine our understanding of how internalized stigma operates in high-risk, quarantine contexts: self-stigmatization directly fosters maladaptive coping and also acts indirectly—predominantly by heightening negative affect and, to a lesser extent, by diminishing inspirational motivation. The differential effect sizes suggest that interventions aimed at ameliorating negative affect (for example, emotion-regulation training and targeted cognitive-behavioral approaches) are likely to yield the largest reductions in maladaptive coping, whereas strategies that bolster goal-directed motivation and psychological empowerment may provide complementary benefits.

5. Practical Implications

The following practical implications are grounded in data collected during the COVID-19 pandemic and therefore are most directly applicable to similar large-scale public-health emergencies or periods of elevated social stress; their generalization to routine, non-pandemic contexts should be tested in future research.

Framed through a social epidemiology lens, these findings highlight the necessity of integrating self-stigma into public health surveillance as a measurable social determinant: routine stigma assessments should be combined with epidemiological data to identify communities at elevated psychosocial risk, enabling targeted allocation of mental health resources and rapid deployment of support services where stigma—and its emotional sequelae—is most concentrated. In pandemic or outbreak settings, such targeted surveillance can help prioritize scarce mental-health personnel and digital support tools to areas experiencing acute stigma-related distress.

Large-scale, community-engaged anti-stigma campaigns are essential to disrupt quarantine-related stereotypes and foster social cohesion: partnering with local leaders and civil society organizations to co-create culturally tailored messages via mass media and social media channels can reduce “othering” of quarantined populations and attenuate the social isolation that exacerbates negative coping behaviors. We note that the effectiveness and uptake of such campaigns may vary outside of outbreak conditions; therefore, implementation in non-pandemic contexts should be accompanied by rigorous evaluation.

Emotional health monitoring must be embedded within quarantine protocols through validated brief scales administered via telehealth or digital check-in platforms: aggregating these data at the population level allows for real-time detection of distress clusters and triggers mobile mental health teams or digital mood support modules, ensuring timely intervention to prevent escalation of maladaptive coping. Pilot testing of these monitoring systems in routine community health settings is recommended before broad non-emergency rollout.

Finally, inspirational motivation interventions—delivered en masse via SMS, community Wi-Fi portals, or peer support testimonials—should be scaled and systematically evaluated for uptake and effectiveness across neighborhoods, while pandemic preparedness plans and funding frameworks explicitly recognize self-stigma and its downstream effects as key social determinants of health, allocating proportional resources to stigma-reduction programs in areas exhibiting the greatest need. We recommend that future studies empirically evaluate whether these intervention strategies retain effectiveness in non-pandemic environments and across diverse cultural and socioeconomic contexts.

6. Limitations and Future Research

This study also has some limitations that should be addressed in future research. On one hand, since this study solely relied on self-reported questionnaires, and all three variables in this research pertain to negative psychological behaviors, there is a possibility of social desirability bias in the responses, which may lead to false data. Current statistical methods are not yet effective in identifying and isolating such biases. Therefore, future research could incorporate behavioral experiments or case interviews to reduce the impact of these biases on the study’s conclusions.

On the other hand, the participants in this study were individuals from quarantine areas, such as those in infectious disease hospitals or high-risk epidemic zones, and the sample size is not large. As a result, it is not sufficient to reveal demographic characteristics effectively. Future studies could consider using longitudinal research designs to explore the temporal effects of self-stigmatization on negative coping strategies among individuals in quarantine areas and the underlying mechanisms. Although we tried to include participants with limited social-media use via community staff and trained assistants, recruitment was mainly online and may over-represent people with better digital access or stronger community ties. This potential selection bias limits generalizability. Future studies should use mixed-mode or probability-based sampling, record social-media use as a covariate, apply weighting to correct sampling imbalances, and replicate findings in offline or non-pandemic settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.W. and K.S.; methodology, Y.W.; software, Y.W.; validation, Y.W., K.S. and S.X.; formal analysis, K.S.; investigation, Y.W.; resources, Y.W.; data curation, Y.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.W.; writing—review and editing, K.S. and S.X.; visualization, Y.W.; supervision, K.S.; project administration, S.X.; funding acquisition, K.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Research on Public Risk Perception, Behavioral Patterns, and Countermeasures in Major Public Health Emergencies grant number 21XXJC04ZD. The APC was funded by Laboratory of Ecological Civilization and Environmental Management of Wenzhou University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the or Ethics Committee of the College of Teacher Education, Wenzhou University, Wenzhou, Zhejiang, China (Approval No. HE2020-0120, effective date: 20 January 2020; expiry date: 18 January 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Wenzhou University for its administrative and technical support. Special thanks also go to all participants in-volved in this study for their time and valuable input. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-4 model) only for translation purposes. The authors have thoroughly reviewed and edited all AI-assisted content and take full responsibility for the accuracy and integrity of the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Barreras, J. L., Bogart, L. M., MacCarthy, S., Klein, D. J., & Pantalone, D. W. (2023). Discrimination and adherence in a cross-sectional study of Latino sexual minority men with HIV: Coping with discrimination as a mediator and coping self-efficacy as a moderator. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 46(6), 1057–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bharti, P., Verma, S. K., & Bajpai, A. (2024). Coping with stigma: Development and initial validation of scale in Indian context. Psychological Studies, 70, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S. L. (2025). Breaking turnover cycles: Integrating transformational leadership and self-awareness into permanency case management [Doctoral dissertation, Regent University]. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, P., Yi, G., Qian, D., Wu, Z., Fu, M., & Peng, H. (2023). Social support mediates the relationship between coping styles and the mental health of medical students. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 16, 1299–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Sousa, L. J. M. (2023). Formulating expectations in times of crisis: The role of inspirational leadership [Master’s thesis, IS-CTE—Instituto Universitario de Lisboa]. [Google Scholar]

- Franks, A. S., Nguyen, R., Xiao, Y. J., & Abbott, D. M. (2024). Psychological distress and behavioral vigilance in response to minority stress and threat among members of the Asian American and Pacific Islander community during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 14, 488–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedli, L., & World Health Organization. (2009). Mental health, resilience and inequalities. WHO Regional Office for Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Gabarrell-Pascuet, A., Lloret-Pineda, A., Franch-Roca, M., Mellor-Marsa, B., Alos-Belenguer, M. D. C., He, Y., El Hafi-Elmokhtari, R., Villalobos, F., Bayes-Marin, I., Aparicio Pareja, L., Álvarez Bobo, O., Espinal Cabezas, M., Osorio, Y., Haro, J. M., & Cristóbal-Narvaez, P. (2023). Impact of perceived discrimination and coping strategies on well-being and mental health in newly arrived migrants in Spain. PLoS ONE, 18(12), e0294295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanis, P., Moisoglou, I., Katsiroumpa, A., Malliarou, M., Vraka, I., Gallos, P., Kalogeropoulou, M., & Papathanasiou, I. V. (2024). Impact of workplace bullying on quiet quitting in nurses: The mediating effect of coping strategies. Healthcare, 12(7), 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X. Y. (2024). The term “abnormal psychology” cues mental illness stigma: A study in China. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology, 18, 18344909241264771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. American Journal of Sociology, 45, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y., Gan, J., & Li, Y. (2025). Effect of negative emotion on prospective memory and its different components. The Journal of General Psychology, 152(1), 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J., Lu, W., Gong, W., & Chen, X. (2023). Inspired in adversity: How inspiration mediates the effects of emotions on coping strategies. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 16, 5185–5196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, S., & Zhang, X. (2025). Do varying levels of self-esteem influence the mental health status of Chinese medical staff? A latent and mediation analysis focused on depression and anxiety. Current Psychology, 44(3), 1738–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, A., Lazarova, M. B., & Liao, H. (2009). Getting everyone on board: The role of inspirational leadership in geographically dispersed teams. Organization Science, 20(1), 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kircher, J. A. (2024). Emotion and cognition across age: Insights from studies on affect, repetitive thinking, stress and inflammation [Doctoral dissertation, University of California Irvine]. [Google Scholar]

- Lasalvia, A., Bonetto, C., van Bortel, T., Cristofalo, D., Brouwers, E., Lanfredi, M., van Weeghel, J., Chang, C.-C., Chee, K.-Y., Harangozó, J., van Audenhove, C., Ola, B., Jorge-Monteiro, F., James, B., Ouali, U., Germanavičius, A., Abdulmalik, J., Ucok, A., Oshodi, Y., & Thornicroft, G. (2025). The impact of self-stigma on empowerment in major depressive disorder: The mediating role of self-esteem and the moderating effects of socioeconomic and cultural context in an international multi-site study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 390, 119802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.-T., & Jin, R. (2024). Vortex of regret: How positive and negative coping strategies correlate with feelings of guilt. Acta Psychologica, 247, 104320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A. A., Farrell, N. R., McKibbin, C. L., & Deacon, B. J. (2016). Comparing treatment relevant etiological explanations for depression and social anxiety: Effects on self-stigmatizing attitudes. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 35(7), 571–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z., & Huang, Y. T. (2025). Perceived stigma, internalized stigma, and mental health of young Chinese men who have sex with men living with HIV/AIDS: Intersection and the importance of “undetectable = untransmittable” status. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. [preprint]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C. P., & Shi, K. (2005). The structure and measurement of transformational leadership. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 37(6), 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, B. G., Cullen, F. T., Struening, E., Shrout, P. E., & Dohrenwend, B. P. (1989). A modified labeling theory approach to mental disorders: An empirical assessment. American Sociological Review, 54(3), 400–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipai, T. P. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic: Depression, anxiety, stigma and impact on mental health. Problems of Social Hygiene, Public Health and History of Medicine, 28(5), 922–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F., Xu, F., Zhang, Y., Zou, J., Ma, Y., & Meng, R. (2025). Psychological capital and learning burnout in college students: The mediating role of coping styles. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 53(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayrhuber, E. A. S., Niederkrotenthaler, T., & Kutalek, R. (2017). “We are survivors and not a virus:” Content analysis of media reporting on Ebola survivors in Liberia. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 11(8), e0005845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moussa, M. T., Lovibond, P. F., & Laube, R. (2001). Psychometric properties of a Chinese version of the 21-item Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS21). Transcultural Mental Health Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Overstreet, N. M., & Quinn, D. M. (2016). The intimate partner violence stigmatization model and barriers to help seeking. In J. C. Chrisler, & D. R. McCreary (Eds.), Social psychological perspectives on stigma (pp. 109–122). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, L., Ren, W., & Fang, R. (2024). Incivility: How tourists cope with relative deprivation. Tourism Management Perspectives, 51, 101246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S., Wang, L., Zheng, L., Luo, J., Mao, J., Qiao, W., Zhu, B., & Wang, W. (2023). Effects of stigma, anxiety and depression, and uncertainty in illness on quality of life in patients with prostate cancer: A cross-sectional analysis. BMC Psychology, 11(1), 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, R., & Aggleton, P. (2003). HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: A conceptual framework and implications for action. Social Science & Medicine, 57(1), 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, W. C., Amy, K., & Lissa, K. (2005). The stigma of mental illness: Explanatory models and methods for change. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 11(3), 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36(4), 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauf, B. (2024). Transformational leadership and its impact on affective organizational commitment [Master’s thesis, Azusa Pacific University]. [Google Scholar]

- Savickas, M. L., & Porfeli, E. J. (2012). Career adapt-abilities scale: Construction, reliability, and measurement equivalence across 13 countries. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(3), 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X., Dong, Z., Zhang, S., Qiao, Y., Zhang, H., & Guo, H. (2025). The relationship between negative emotions and adjustment disorder in young adults: The mediating role of rumination and insomnia. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 16, 1474108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, K., Hongxia, F., Jianming, J., Wendong, L., Zhaoli, S., Jing, G., Xuefeng, C., Jiafang, L., & Weipeng, H. (2003). The risk perceptions of SARS and socio-psychological behaviors of urban people in China. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 35(4), 546–554. [Google Scholar]

- Szepietowska, M., Stefaniak, A. A., Krajewski, P. K., & Matusiak, L. (2024). Females may have less severe acne, but they suffer more: A prospective cross-sectional study on psychosocial consequences in 104 consecutive Polish acne patients. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(1), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, L. H., Khan, S., du Plessis, E., Lazarus, L., Reza-Paul, S., Hafeez Ur Rahman, S., Pasha, A., & Lorway, R. (2013). Beyond internalised stigma: Daily moralities and subjectivity among self-identified kothis in Karnataka, South India. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 15(10), 1237–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torales, J., O’Higgins, M., Castaldelli-Maia, J. M., & Ventriglio, A. (2020). The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 66(4), 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torous, J., Myrick, K. J., Rauseo-Ricupero, N., & Firth, J. (2020). Digital mental health and COVID-19: Using technology today to accelerate the curve on access and quality tomorrow. JMIR Mental Health, 7(3), e18848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, V. R. (2024). Supervisor transformational leadership characteristics as contributors to nursing personnel psychological well-being. Grand Canyon University. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Q., Wu, H., & Zhang, R. (2024). Using online negative emotions to predict risk-coping behaviors in the relocation of Beijing municipal government. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 28337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X., & Bartol, K. M. (2010). Linking empowering leadership and employee creativity: The influence of psychological empowerment, intrinsic motivation, and creative process engagement. Academy of Management Journal, 53(1), 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H., & Long, L. R. (2004). Statistical tests and control methods of common method bias. Advances in Psychological Science, 12(6), 942–950. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, M., Liu, B., Ji, J., Ren, L., Wang, X., & Li, F. (2024). The relationship between negative coping styles, psychological resilience, and positive coping styles in military personnel: A cross-lagged analysis. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 17, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).