The Relationship Between Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction, Fear of Missing Out, and University Student Depression: A Two-Year Follow-Up Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Basic Psychological Needs Scale (BPNS)

2.2.2. Fear of Missing Out Scale (FoMOs)

2.2.3. The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Common Method Bias Test

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

3.3. Longitudinal Measurement Invariance Test

3.4. Unconditional Latent Growth Model

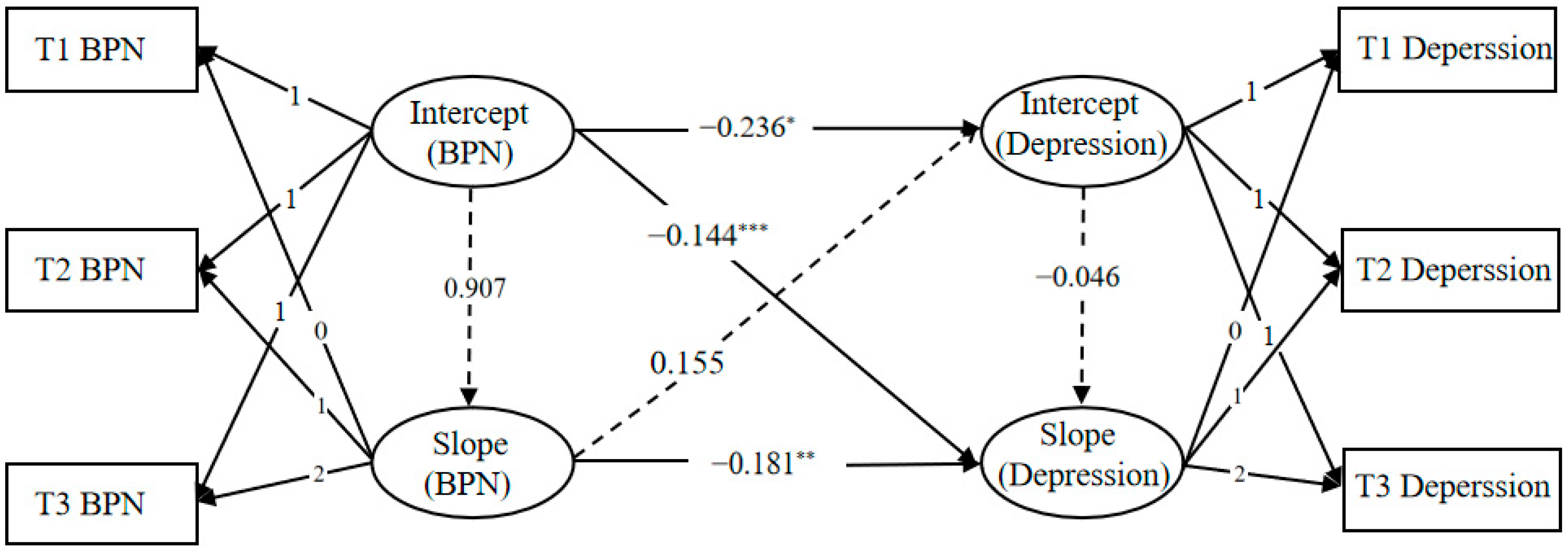

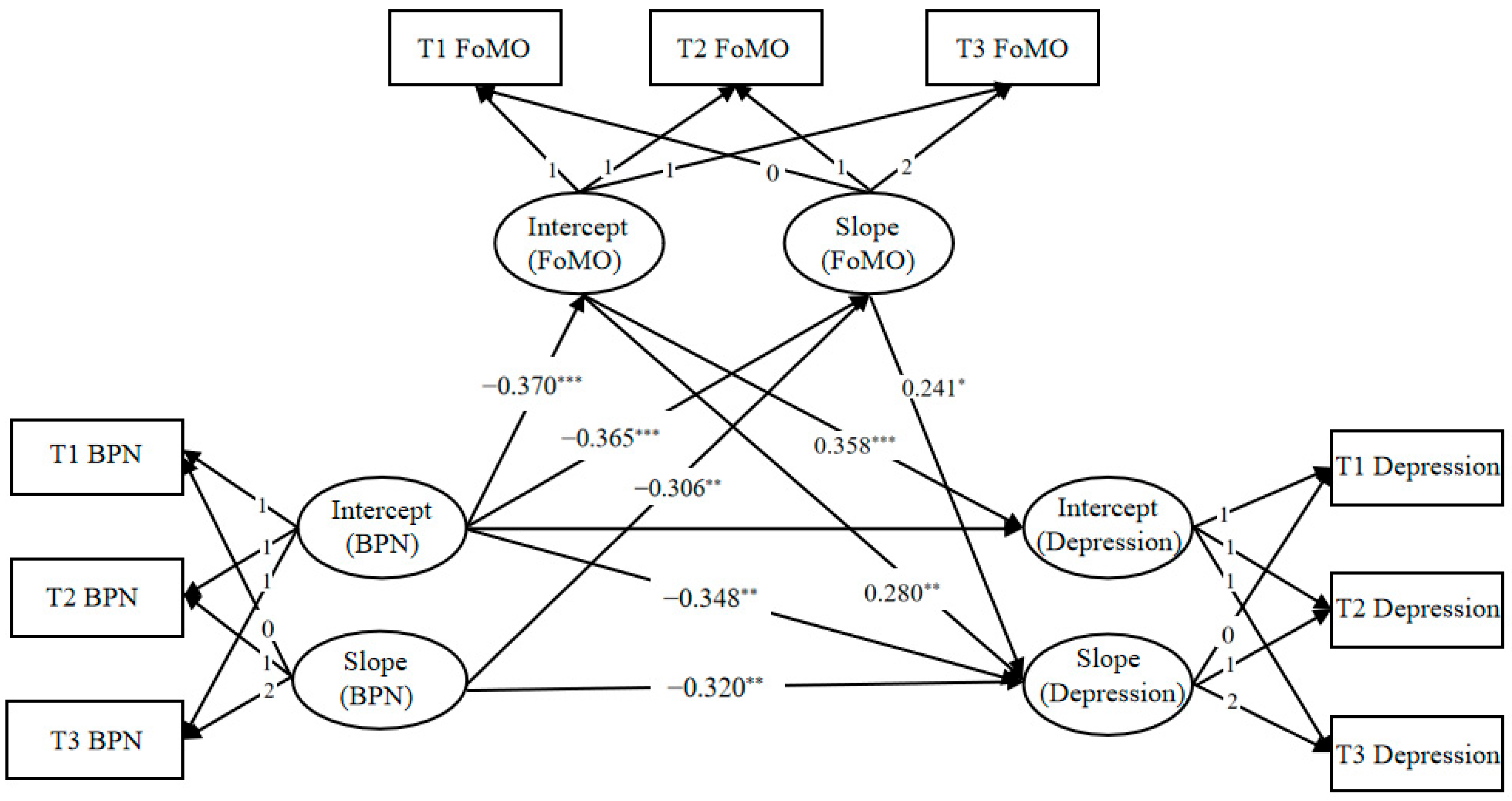

3.5. Conditional Latent Growth Model for Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction, FoMO, and Depression

3.6. The Longitudinal Mediation of FoMO

3.7. Gender Differences in Longitudinal Mediation Models

4. Discussion

4.1. Trends in University Students’ Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction, FoMO, and Depression

4.2. Direct Effects of Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction on Depression Trends

4.3. Longitudinal Mediation of FoMO

4.4. Research Implications and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BPNS | Basic psychological need satisfaction |

| FoMO | Fear of missing out |

References

- Alt, D. (2018). Students’ wellbeing, fear of missing out, and social media engagement for leisure in higher education learning environments. Current Psychology, 37(1), 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, D., & Boniel-Nissim, M. (2018). Links between adolescents’ deep and surface learning approaches, problematic internet use, and fear of missing out (FoMO). Internet Interventions, 13, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, R. A., Lowe, R., & Clair, A. (2011). The relationship between basic need satisfaction and emotional eating in obesity. Australian Journal of Psychology, 63(4), 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Z. G., Krieger, H., & LeRoy, A. S. (2016). Fear of missing out: Relationships with depression, mindfulness, and physical symptoms. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 2(3), 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyens, I., Frison, E., & Eggermont, S. (2016). “I don’t want to miss a thing”: Adolescents’ fear of missing out and its relationship to adolescents’ social needs, Facebook use, and Facebook related stress. Computers in Human Behavior, 64, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, A. K., & Arshad, T. (2021). The relationship between basic psychological needs and phubbing: Fear of missing out as the mediator. PsyCh Journal, 10(6), 916–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruana, E. J., Roman, M., Hernández-Sánchez, J., & Solli, P. (2015). Longitudinal studies. Journal of Thoracic Disease, 7(11), E537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casale, S., Rugai, L., & Fioravanti, G. (2018). Exploring the role of positive meta cognitions in explaining the association between the fear of missing out and social media addiction. Addictive Behaviors, 85, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling—A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(3), 464–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Zhang, Y., & Yu, G. (2022). Prevalence of mental health problems among college students in Chinese mainland from 2010 to 2020: A meta-analysis. Advances in Psychological Science, 30(5), 991–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M., & Berman, S. L. (2012). Globalization and identity development: A Chinese perspective. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2012(138), 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compare, A., Zarbo, C., Shonin, E., Van Gordon, W., & Marconi, C. (2014). Emotional regulation and depression: A potential mediator between heart and mind. Cardiovascular Psychiatry and Neurology, 1, 324374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, S., Soenens, B., Gugliandolo, M. C., Cuzzocrea, F., & Larcan, R. (2015). The mediating role of experiences of need satisfaction in associations between parental psychological control and internalizing problems: A study among italian college students. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 24(4), 1106–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). Motivation, personality, and development within embedded social contexts: An overview of self-determination theory. In The oxford handbook of human motivation (Vol. 18, pp. 85–107). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, L., Xin, X., & Xu, J. (2019). Relation of anxiety and depression symptoms to parental autonomy support and basic psychological need satisfaction in senior one students. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 33(11), 875–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, A., Yossatorn, Y., Kaur, P., & Chen, S. (2018). Online social media fatigue and psychological wellbeing—A study of compulsive use, fear of missing out, fatigue, anxiety and depression. International Journal of Information Management, 40, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, F., Li, Q., Li, X., Li, Q., & Wang, M. (2023). Impact of perceived social support on fear of missing out (FoMO): A moderated mediation model. Current Psychology, 42(1), 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhai, J. D., Levine, J. C., Dvorak, R. D., & Hall, B. J. (2016). Fear of missing out, need for touch, anxiety and depression are related to problematic smartphone use. Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhai, J. D., Yang, H., & Montag, C. (2020). Fear of missing out (FOMO): Overview, theoretical underpinnings, and literature review on relations with severity of negative affectivity and problematic technology use. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry, 43(2), 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, E. I. (2017). The 52 symptoms of major depression: Lack of content overlap among seven common depression scales. Journal of Affective Disorders, 208, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fried, E. I., & Nesse, R. M. (2015). Depression is not a consistent syndrome: An investigation of unique symptom patterns in the STAR*D study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 172, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, M. (2003). The role of autonomy support and autonomy orientation in prosocial behavior engagement. Motivation and Emotion, 27(3), 199–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y. (2014). The new trend in mediating effect research: Research design and data statistical methods. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 28(8), 584–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Burden of Disease. (2021). GBD report on where are mental disorders most common? Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. [Google Scholar]

- Gronemann, F. H., Jorgensen, M. B., Nordentoft, M., Andersen, P. K., & Osler, M. (2021). Treatment-resistant depression and risk of all-cause mortality and suicidality in Danish patients with major depression. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 135, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M., & Sharma, A. (2021). Fear of missing out: A brief overview of origin, theoretical underpinnings and relationship with mental health. World Journal of Clinical Cases, 9(19), 4881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamama, L., & Hamama-Raz, Y. (2021). Meaning in life, self-control, positive and negative affect: Exploring gender differences among adolescents. Youth & Society, 53, 699–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrman, H., Patel, V., Kieling, C., Berk, M., Buchweitz, C., Cuijpers, P., Furukawa, T. A., Kessler, R. C., Kohrt, B. A., Maj, M., & Wolpert, M. (2022). Time for united action on depression: A Lancet-World Psychiatric Association Commission. The Lancet, 399(10328), 957–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J. P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, N. H., Holding, A. C., Verner-Filion, J., Sheldon, K. M., & Koestner, R. (2019). The path from intrinsic aspirations to subjective well-being is mediated by changes in basic psychological need satisfaction and autonomous motivation: A large prospective test. Motivation and Emotion, 43(2), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., Zhang, L., Li, N., & Dai, Y. (2024). Relationships among loneliness, childhood emotional trauma. Basic psychological needs and positive coping in college students. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 38(12), 1086–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S. A. S., Pauzi, N. W. M., Dahlan, A., & Vetrayan, J. (2022). Fear of missing out (FoMO) and its relation with depression and anxiety among university students. Environment-Behaviour Proceedings Journal, 7(20), 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, T. L., Lowry, P. B., Wallace, L., & Warkentin, M. (2017). The effect of belongingness on obsessive-compulsive disorder in the use of online social networks. Journal of Management Information Systems, 34(2), 560–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanović, V., Tomašević, A., Šakan, D., Lazić, M., Gavrilov-Jerković, V., Zotović-Kostić, M., & Obradović, V. (2024). The role of basic psychological needs in the relationships between identity orientations and adolescent mental health: A protocol for a longitudinal study. PLoS ONE, 19(1), e0296507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C., Altavilla, D., Ronconi, A., & Aceto, P. (2016). Fear of missing out (FOMO) is associated with activation of the right middle temporal gyrus during inclusion social cue. Computers in Human Behavior, 61, 516–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q., Wang, J., Zhao, S., & Jia, Y. (2019). Validity and reliability of the Chinese version of the Fear of Missing Out scale in college students. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 33(4), 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Y., Li, J., Hu, X., Chen, Y., & Li, D. (2025). The influence of helicopter parenting on the mobile phone dependency among college students: Longitudinal mediating effect of basic psychological needs. Psychological Development and Education, 41(3), 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., Lin, L., Lü, Y., Wei, C., Zhou, Y., & Chen, X. (2013). Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the basic psychological needs Scale. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 27(10), 791–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M., Rao, Y., Deng, Z., & Wu, B. (2024). The relationship between fear of missing out and depression among college students: The mediating effect of nomophobia and social media fatigue, and the moderating effect of mindfulness. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 32(2), 361–365+370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Shen, L., Wu, X., Zhen, R., & Zhou, X. (2024). Basic psychological need satisfaction and depression in adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: The mediating roles of feelings of safety and rumination. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 55(1), 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, D. (2015). Individual development from an interactional perspective (psychology revivals): A longitudinal study. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martela, F., & Ryan, R. M. (2016). The benefits of benevolence: Basic psychological needs, beneficence, and the enhancement of well-being. Journal of Personality, 84(6), 750–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meynadier, J., Malouff, J. M., Schutte, N. S., Loi, N. M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2025). Relationships between social media addiction, social media use metacognitions, depression, anxiety, fear of missing out, loneliness, and mindfulness. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, J. D., & Hamaker, E. L. (2021). Three extensions of the random intercept cross-lagged panel model. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 28(4), 638–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2012). Emotion regulation and psychopathology: The role of gender. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 8(1), 161–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olbert, C. M., Gala, G. J., & Tupler, L. A. (2014). Quantifying heterogeneity attributable to polythetic diagnostic criteria: Theoretical framework and empirical application. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 123, 452–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsolini, L., Latini, R., Pompili, M., Serafini, G., Volpe, U., Vellante, F., & De Berardis, D. (2020). Understanding the complex of suicide in depression: From research to clinics. Psychiatry Investigation, 17(3), 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H. J., & Park, Y. B. (2024). Negative upward comparison and relative deprivation: Sequential mediators between social networking service usage and loneliness. Current Psychology, 43(10), 9141–9151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, E. L., & Brier, S. (2001). Friendsickness in the transition to college: Precollege predictors and college adjustment correlates. Journal of Counseling & Development, 79(1), 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, L., Zhang, G., He, K., Mo, X., & Guo, L. (2024). Longitudinal impact of self-compassion on emotional issues among college students:A dual-role model of basic psychological needs satisfaction. Chine Journal of Health Psychology, 32(1), 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proverbio, A. M., Adorni, R., Zani, A., & Trestianu, L. (2009). Sex differences in the brain response to affective scenes with or without humans. Neuropsychologia, 47(12), 2374–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Przybylski, A. K., Murayama, K., DeHaan, C. R., & Gladwell, V. (2013). Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1841–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W., & Ye, Y. (2024). The influence of maladaptive cognition of internet use on depression among college students: The chain mediating role of online risky behavior and cyber victimization. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 32(4), 831–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed-Fitzke, K., & Lucier-Greer, M. (2021). Basic psychological need satisfaction and frustration: Profiles among emerging adult college students and links to well-being. Contemporary Family Therapy, 43(1), 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reer, F., Tang, W. Y., & Quandt, T. (2019). Psychosocial well-being and social media engagement: The mediating roles of social comparison orientation and fear of missing out. New Media & Society, 21(7), 1486–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J., & Lee, W. (2019). A neuroscientific perspective on basic psychological needs. Journal of Personality, 87(1), 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2008). Self-determination theory and the role of basic psychological needs in personality and the organization of behavior. In O. P. John, R. W. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (3rd ed., pp. 654–678). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, K., Zhao, M., Zhang, Z., Song, X., Chen, Z., Li, H., Bai, M., & Jiao, S. (2024). Psychological screening and crisis intervention research among university students. Psychological Exploration, 44(5), 464–473. [Google Scholar]

- Stead, H., & Bibby, P. A. (2017). Personality, fear of missing out and problematic internet use and their relationship to subjective well-being. Computers in Human Behavior, 76, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M., & Ryan, R. M. (2013). On psychological growth and vulnerability: Basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration as a unifying principle. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 23(3), 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M., Ryan, R. M., & Soenens, B. (2020). Basic psychological need theory: Advancements, critical themes, and future directions. Motivation and Emotion, 44(1), 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S., Qin, G., Tu, S., Li, S., Yirimuwen, & Lin, S. (2024). Psychological maltreatment in childhood affects fear of missing out in adulthood: The mediating path of basic psychological needs and the moderating influence of conscientiousness. Current Psychology, 43(7), 5987–5998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G., & Chen, Y. N. K. (2010). Collectivism, relations, and Chinese communication. Chinese Journal of Communication, 3(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegmann, E., Oberst, U., Stodt, B., & Brand, M. (2017). Online-specific fear of missing out and Internet-use expectancies contribute to symptoms of Internet-communication disorder. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 5, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M., Mallinckrodt, B., Arterberry, B. J., Liu, S., & Wang, K. T. (2021). Latent profile analysis of interpersonal problems: Attachment, basic psychological need frustration, and psychological outcomes. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 68(4), 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, A. H., Gbedemah, M., Martinez, A. M., Nash, D., Galea, S., & Goodwin, R. D. (2018). Trends in depression prevalence in the USA from 2005 to 2015: Widening disparities in vulnerable groups. Psychological Medicine, 48(8), 1308–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z. (2017). Causal inference and analysis in empirical studies. Journal of Psychological Science, 40(1), 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2018). WHO report on surveillance of antibiotic consumption: 2016–2018 early implementation. WHO. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, X., & Zheng, X. (2022). The effect of parental phubbing on depression in Chinese junior high school students: The mediating roles of basic psychological need satisfaction satisfaction and self-esteem. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 868354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z., Peng, H., & Xin, S. (2024). A longitudinal study on depression and anxiety among Chinese adolescents in the late phase of the COVID-19 pandemic: The trajectories, antecedents, and outcomes. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 56(4), 482–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L., & Bai, S. (2025). The relationship between anxiety, depression and social comparison in an era of digital media. Advances in Psychological Science, 33(1), 92–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H., & Long, L. (2004). Statistical remedies for common method biases. Advances in Psychological Science, 12(6), 942–950. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L., Wang, H., Geng, J., & Lei, L. (2024). Cyberbullying victimization and depression among college students: The moderating roles of psychological capital and peer support. Journal of Psychological Science, 47(4), 981–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| T1BPNS | T2BPNS | T3BPNS | T1FoMO | T2FoMO | T3FoMO | T1Depression | T2Depression | T3Depression | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1BPNS | 1 | ||||||||

| T2BPNS | 0.243 *** | 1 | |||||||

| T3BPNS | 0.221 *** | 0.394 *** | 1 | ||||||

| T1FoMO | −0.129 *** | −0.089 *** | −0.090 * | 1 | |||||

| T2FoMO | −0.171 *** | −0.172 *** | −0.138 *** | 0.308 *** | 1 | ||||

| T3FoMO | −0.200 *** | −0.227 *** | −0.265 *** | 0.296 *** | 0.478 *** | 1 | |||

| T1Depression | −0.154 *** | −0.096 ** | −0.167 *** | 0.178 *** | 0.096 ** | 0.129 *** | 1 | ||

| T2Depression | −0.250 *** | −0.270 *** | −0.249 *** | 0.256 *** | 0.326 *** | 0.378 *** | 0.338 *** | 1 | |

| T3Depression | −0.297 *** | −0.349 *** | −0.355 *** | 0.307 *** | 0.359 *** | 0.449 *** | 0.299 *** | 0.669 *** | 1 |

| gender | 0.016 | −0.020 | −0.037 | 0.033 | 0.011 | 0.034 | 0.027 | 0.019 | 0.028 |

| M | 4.750 | 4.427 | 4.093 | 3.014 | 3.191 | 3.354 | 1.803 | 1.991 | 2.166 |

| SD | 0.425 | 0.445 | 0.514 | 0.277 | 0.295 | 0.369 | 0.160 | 0.141 | 0.177 |

| Model | χ2 | df | CFI | RMSEA(90% CI) | SRMR | Model Comparison | ∆CFI | ΔRMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction | ||||||||

| M1:Configural Invariance | 575.925 | 456 | 0.960 | 0.019 (0.014, 0.023) | 0.050 | |||

| M2: Metric Invariance | 619.333 | 492 | 0.958 | 0.019 (0.014, 0.023) | 0.054 | M2-M1 | −0.002 | 0.000 |

| M3: Scalar Invariance | 661.156 | 528 | 0.956 | 0.018 (0.013, 0.023) | 0.055 | M3-M2 | −0.002 | −0.001 |

| FoMO | ||||||||

| M1: Configural Invariance | 70.278 | 60 | 0.996 | 0.015 (0.000, 0.028) | 0.019 | |||

| M2: Metric Invariance | 80.818 | 74 | 0.998 | 0.011 (0.000, 0.024) | 0.034 | M2-M1 | 0.002 | −0.004 |

| M3: Scalar Invariance | 93.215 | 88 | 0.998 | 0.009 (0.000, 0.022) | 0.036 | M3-M2 | 0.000 | −0.002 |

| Depression | ||||||||

| M1: Configural Invariance | 582.461 | 510 | 0.976 | 0.014 (0.007, 0.019) | 0.029 | |||

| M2: Metric Invariance | 603.114 | 548 | 0.982 | 0.012 (0.000, 0.017) | 0.032 | M2-M1 | 0.006 | −0.002 |

| M3: Scalar Invariance | 644.874 | 586 | 0.981 | 0.012 (0.002, 0.017) | 0.035 | M3-M2 | −0.001 | 0.000 |

| Model | χ2 | df | RMSEA | CFI | TLI | Mean (Variance) | r | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | Slope | |||||||

| BPNS | 0.093 | 1 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.015 | 90.281 *** | −6.239 *** | 0.829 |

| FoMO | 0.448 | 1 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.006 | 24.132 *** | 1.36 *** | 0.324 |

| Depression | 2.252 | 1 | 0.041 | 0.998 | 0.993 | 36.142 *** | 3.602 *** | 0.348 |

| Direct Paths | β [95% CI] | SE | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| BPNS intercept → FOMO intercept | −0.370 [−0.517, −0.220] | 0.090 | <0.001 |

| BPNS intercept → FOMO slope | −0.365 [−0.517, −0.168] | 0.106 | 0.001 |

| BPNS slope → FOMO slope | −0.337 [−0.500, −0.143] | 0.110 | 0.002 |

| BPNS intercept → Depression intercept | −0.306 [−0.466, −0.143] | 0.098 | 0.002 |

| BPNS intercept → Depression slope | −0.348 [−0.519, −0.163] | 0.112 | 0.002 |

| BPNS slope → Depression slope | −0.320 [−0.514, −0.135] | 0.118 | 0.007 |

| FOMO intercept → Depression intercept | 0.358 [0.183, 0.513] | 0.100 | <0.001 |

| FOMO intercept → Depression slope | 0.280 [0.109, 0.450] | 0.104 | 0.007 |

| FOMO slope → Depression slope | 0.241 [0.034, 0.413] | 0.116 | 0.039 |

| Indirect Paths | β [95% CI] | p |

|---|---|---|

| BPNS intercept → FOMO intercept → Depression intercept | −0.132 [−0.231, −0.070] | 0.007 |

| BPNS intercept → FOMO intercept → Depression slope | −0.104 [−0.206, −0.042] | 0.036 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, X.; Ren, Z.; Xin, T. The Relationship Between Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction, Fear of Missing Out, and University Student Depression: A Two-Year Follow-Up Study. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1379. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101379

Zhao X, Ren Z, Xin T. The Relationship Between Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction, Fear of Missing Out, and University Student Depression: A Two-Year Follow-Up Study. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1379. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101379

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Xintong, Zixian Ren, and Tao Xin. 2025. "The Relationship Between Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction, Fear of Missing Out, and University Student Depression: A Two-Year Follow-Up Study" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 10: 1379. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101379

APA StyleZhao, X., Ren, Z., & Xin, T. (2025). The Relationship Between Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction, Fear of Missing Out, and University Student Depression: A Two-Year Follow-Up Study. Behavioral Sciences, 15(10), 1379. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101379