Using Network Analysis to Identify Central Facets of Androgynous Development Between Sexes in Chinese Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Gender-Typed Traits

2.2.2. Sex

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

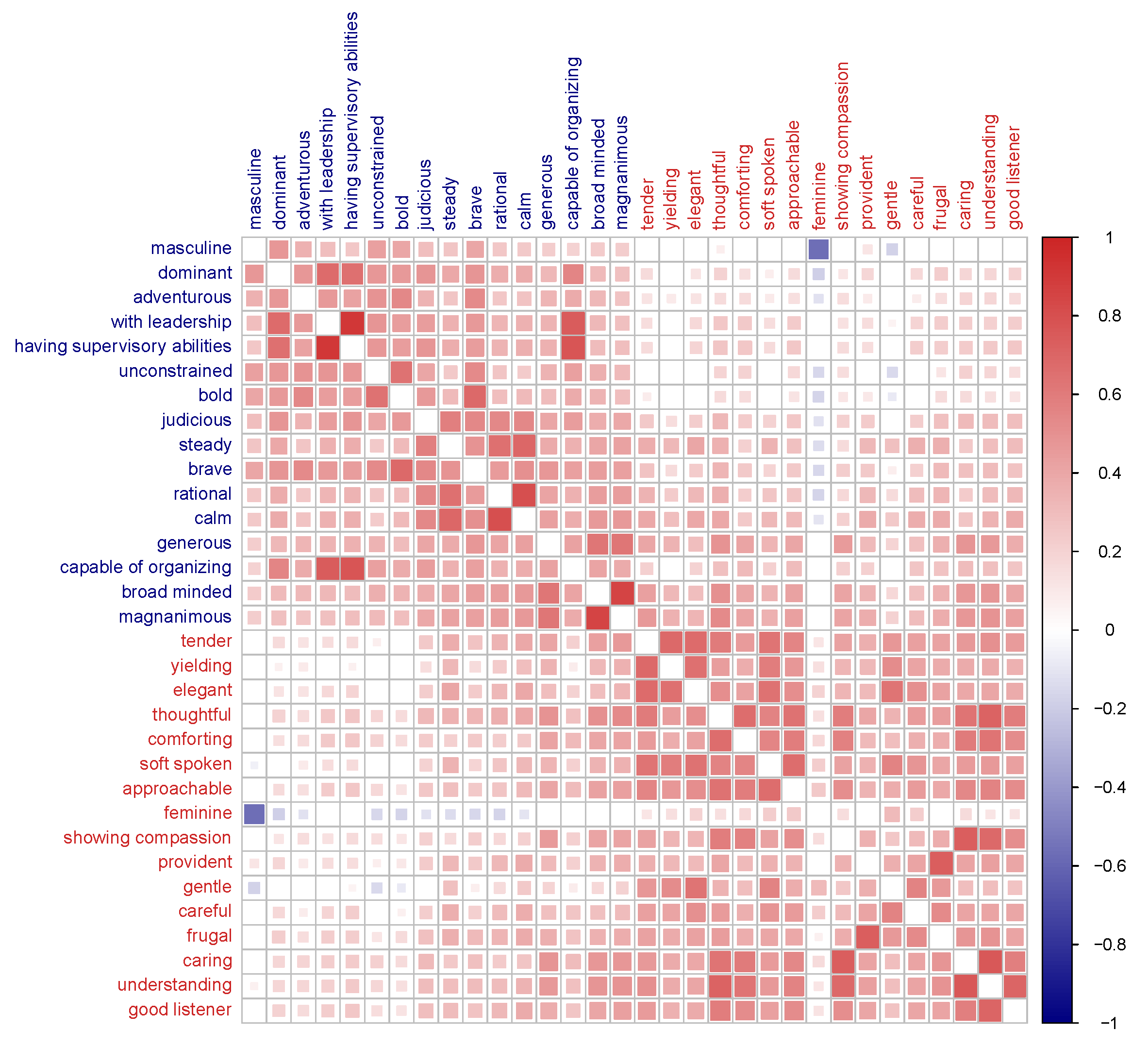

3.1. Descriptive Statistics, Correlations, and Sex Differences

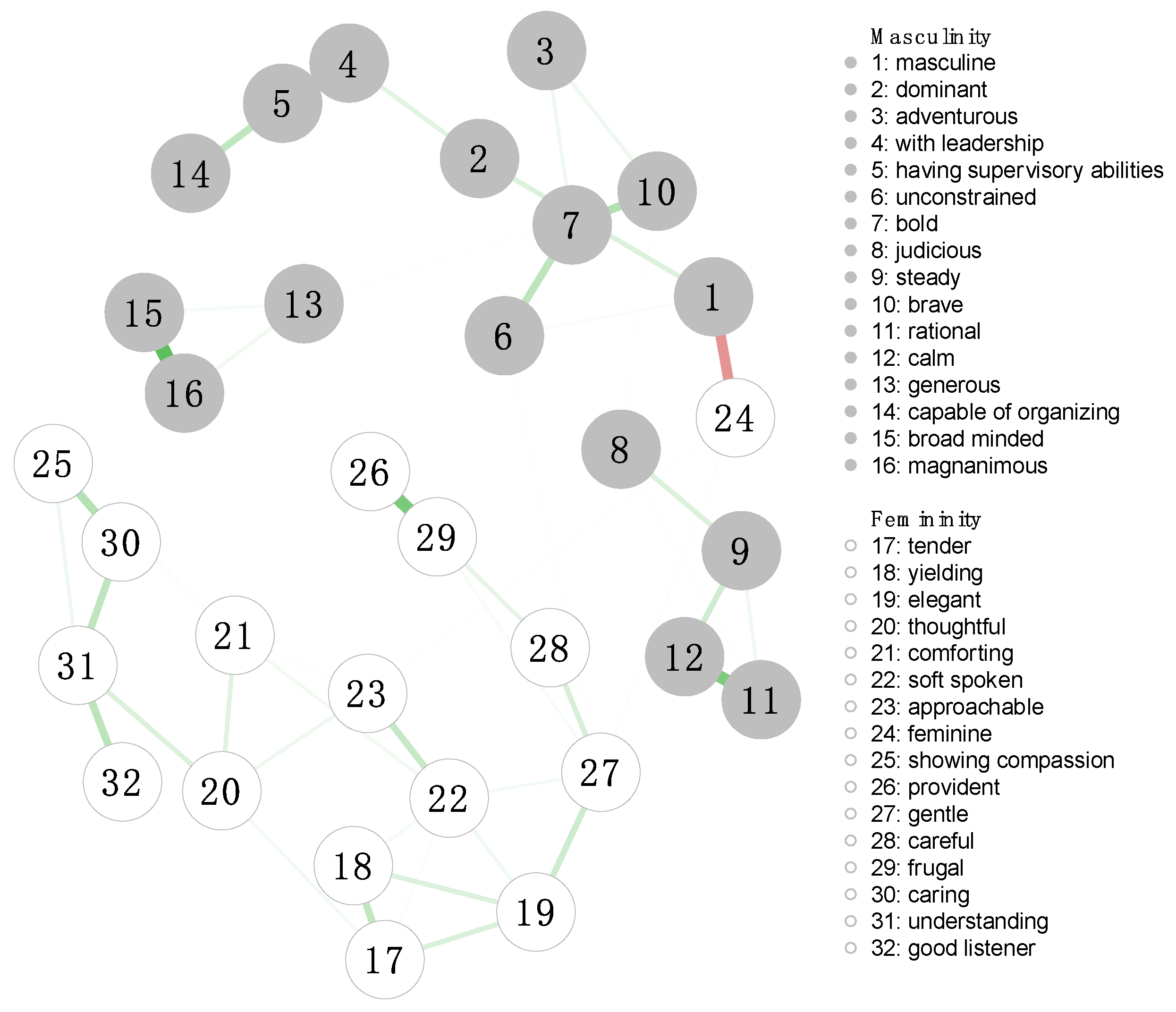

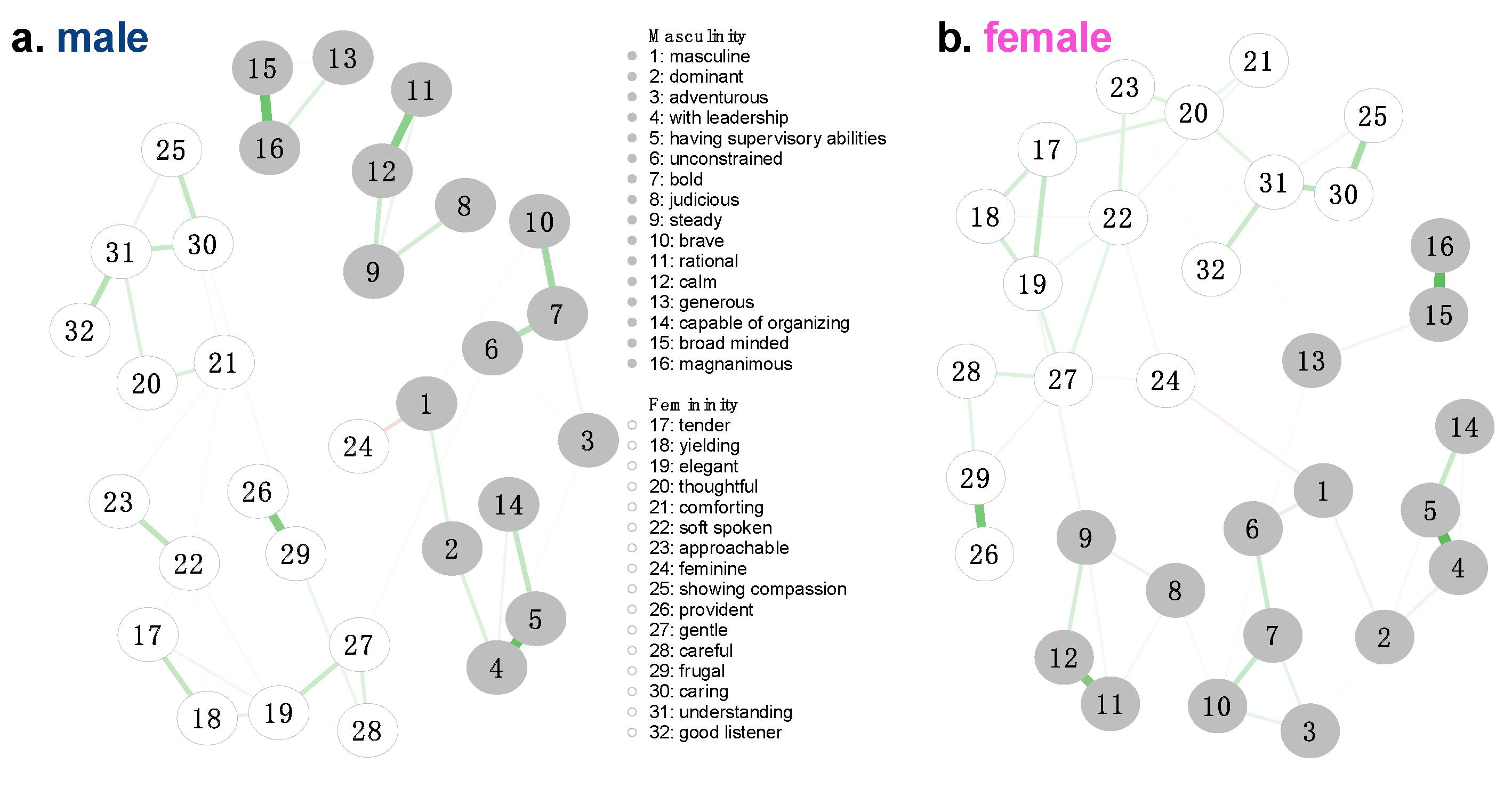

3.2. Network Structure

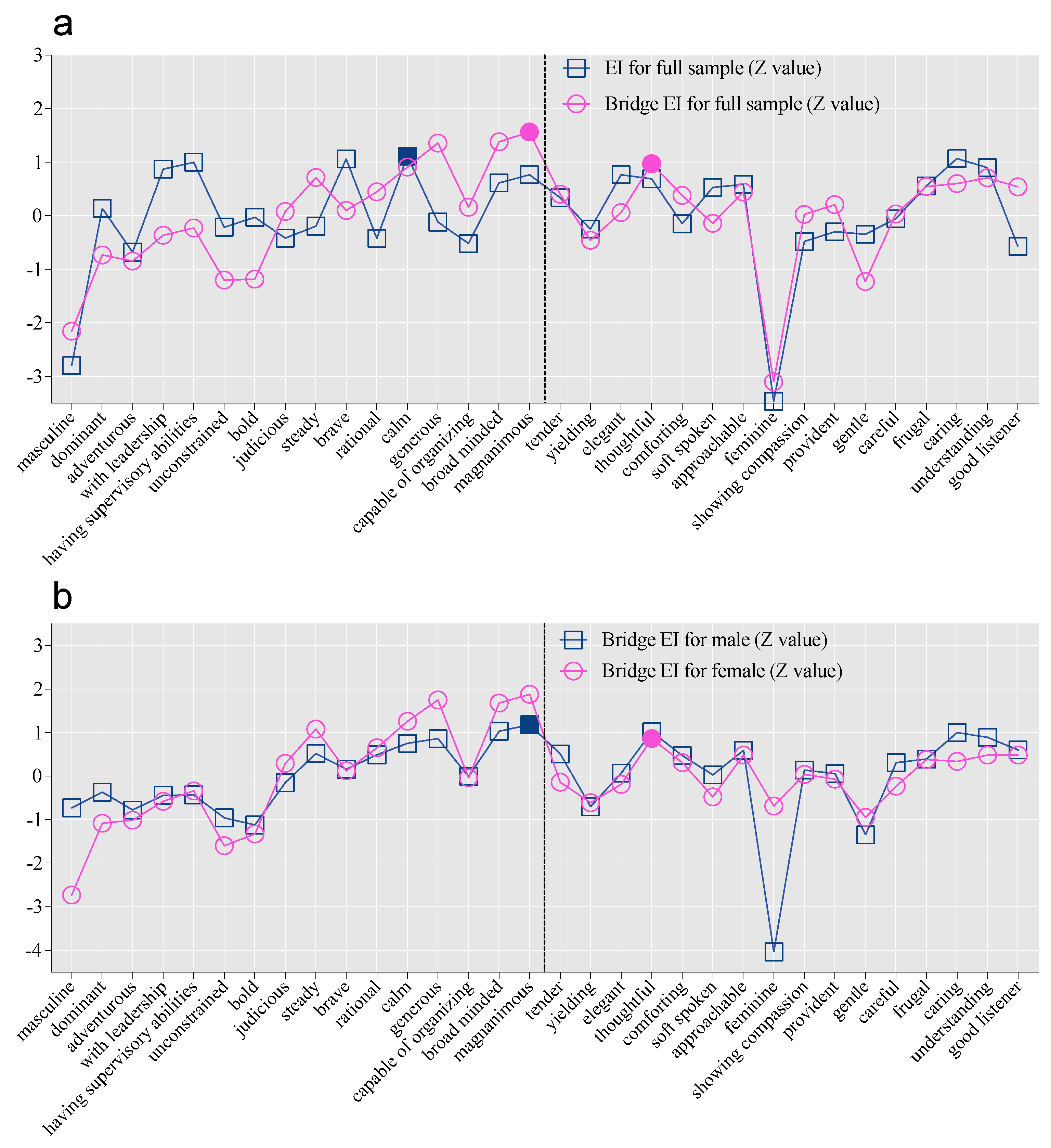

3.3. EI and Bridge EI Metrics

3.4. Network Accuracy and Stability

3.5. Network Comparison

4. Discussion

4.1. Central Role of “Magnanimous” in Male Androgynous Development

4.2. Central Role of “Thoughtful” in Female Androgynous Development

4.3. Flexible Gender Development: Cultural Perspectives

4.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

4.5. Practice Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | See https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/magnanimous (accessed on 17 June 2025). |

| 2 | See https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/thoughtful (accessed on 17 June 2025). |

References

- Bem, S. L. (1981). Gender schema theory: A cognitive account of sex typing. Psychological Review, 88(4), 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bem, S. L. (1984). Androgyny and gender schema theory: A conceptual and empirical integration. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 32, 179–226. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Berggren, M., & Bergh, R. (2025). Simpson’s gender-equality paradox. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 122(23), e2422247122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borsboom, D., & Cramer, A. O. J. (2013). Network analysis: An integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9, 91–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosson, J. K., Vandello, J. A., & Buckner, C. E. (2018). The psychology of sex and gender. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Cahill, B., & Adams, E. (1997). An exploratory study of early childhood teachers’ attitudes toward gender roles. Sex Roles, 36(7), 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F., Zhao, X., Qian, X., Wang, W., Zhou, Y., & Xu, J. (2025). Relationships among sleep quality, anxiety, and depression among Chinese nurses: A network analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 389, 119587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A. H., Woo, W., & Diekman, A. B. (2012). Social role theory of sex differences and similarities: A current appraisal. In The developmental social psychology of gender (pp. 123–174). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Epskamp, S., Borsboom, D., & Fried, E. I. (2018). Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behavior Research Methods, 50(1), 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S., Cramer, A. O. J., Waldorp, L. J., Schmittmann, V. D., & Borsboom, D. (2012). qgraph: Network visualizations of relationships in psychometric data. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(4), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinman, S. (1981). Why is cross-sex-role behavior more approved for girls than for boys? A status characteristic approach. Sex Roles, 7(3), 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J. H., Hastie, T., & Tibshirani, R. (2010). Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. Journal of Statistical Software, 33(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fruchterman, T. M. J., & Reingold, E. M. (1991). Graph drawing by force-directed placement. Software: Practice and Experience, 21(11), 1129–1164. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, P., & Steiger, R. L. (2022). Sexual orientation as gendered to the everyday perceiver. Sex Roles, 87(3), 117–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, N., Badura, K. L., Newman, D. A., & Speach, M. E. P. (2021). Gender, “masculinity,” and “femininity”: A meta-analytic review of gender differences in agency and communion. Psychological Bulletin, 147(10), 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, J. S., Bigler, R. S., Joel, D., Tate, C. C., & van Anders, S. M. (2019). The future of sex and gender in psychology: Five challenges to the gender binary. American Psychologist, 74(2), 171–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, P. J., Ma, R., & McNally, R. J. (2021). Bridge centrality: A network approach to understanding comorbidity. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 56(2), 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, S., & Anderson, J. R. (2024). The relationship between masculinity and men’s COVID-19 safety precautions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychology of Men & Masculinities, 25(3), 240–251. [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel, M. S. (2000). The gendered society. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Korlat, S., Holzer, J., Schultes, M. T., Buerger, S., Schober, B., Spiel, C., & Kollmayer, M. (2022). Benefits of psychological androgyny in adolescence: The role of gender role self-concept in school-related well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 856758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krahe, B. (2018). Gendered self-concept and the aggressive expression of driving anger: Positive femininity buffers negative masculinity. Sex Roles, 79(1–2), 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G., Cheng, Y., Barnhart, W. R., Song, J., Lu, T., & He, J. (2023). A network analysis of disordered eating symptoms, big-five personality traits, and psychological distress in Chinese adults. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 56(10), 1842–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J., Zou, L., Lin, W., Becker, B., Yeung, A., Cuijpers, P., & Li, H. (2021). Does gender role explain a high risk of depression? A meta-analytic review of 40 years of evidence. Journal of Affective Disorders, 294, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.-Z., Huang, H.-X., Jia, F.-Q., Gong, Q., Huang, Q., & Li, X. (2011). A new sex-role inventory (CSRI-50) indicates changes of sex role among Chinese college students. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 43, 639–649. Available online: https://journal.psych.ac.cn/acps/EN/abstract/abstract623.shtml (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Liu, W., Li, Z., Ding, C., Wang, X., & Chen, H. (2024). A holistic view of gender traits and personality traits predict human health. Personality and Individual Differences, 222, 112601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J. H., & Van Wijk, C. H. (2021). The endorsement of traditional masculine ideology by South African Navy men: A research report. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 29(1), 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullarkey, M. C., Marchetti, I., & Beevers, C. G. (2019). Using network analysis to identify central symptoms of adolescent depression. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 48(4), 656–668. [Google Scholar]

- Olavarría, J. A. (2023). Reflections on orders of gender, cultural mandates and masculinities in Latin America. Men and Masculinities, 26(5), 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opsahl, T., Agneessens, F., & Skvoretz, J. (2010). Node centrality in weighted networks: Generalizing degree and shortest paths. Social Networks, 32(3), 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, T., & Lajunen, T. (2005). Why are there sex differences in risky driving? The relationship between sex and gender-role on aggressive driving, traffic offences, and accident involvement among young Turkish drivers. Aggressive Behavior, 31(6), 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinaugh, D. J., Millner, A. J., & McNally, R. J. (2016). Identifying highly influential nodes in the complicated grief network. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125(6), 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safraou, I., Errajaa, K., & Razgallah, M. (2025). The direct and indirect effect of gender role orientation on entrepreneurial intention. Current Psychology, 44(11), 11103–11125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandnabba, N. K., & Ahlberg, C. (1999). Parents’ attitudes and expectations about children’s cross-gender behavior. Sex Roles, 40(3), 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirin, S. R., McCreary, D. R., & Mahalik, J. R. (2004). Differential reactions to men and women’s gender role transgressions: Perceptions of social status, sexual orientation, and value dissimilarity. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 12(2), 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, O. D., McHale, S. M., Wood, D., & Telfer, N. A. (2019). Gender-Typed Personality Qualities and African American Youth’s School Functioning. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(4), 680–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, J. T., Helmreich, R. L., & Stapp, J. (1974). The personal attributes questionnaire: A measure of sex role stereotypes and masculinity-femininity. University of Texas. [Google Scholar]

- van Borkulo, C., Boschloo, L., Borsboom, D., Penninx, B. W. J. H., Waldorp, L. J., & Schoevers, R. A. (2015). Association of symptom network structure with the course of depression. JAMA Psychiatry, 72(12), 1219–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vescio, T. K., Schermerhorn, N. E., Gallegos, J. M., & Laubach, M. L. (2021). The affective consequences of threats to masculinity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 97, 104195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y. J., Ho, M.-H. R., Wang, S.-Y., & Miller, I. S. K. (2017). Meta-analyses of the relationship between conformity to masculine norms and mental health-related outcomes. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(1), 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, J., Shi, J., Liu, S., Endendijk, J. J., & Wu, X. (2024). The relative importance of paternal versus maternal involvement for chinese adolescents’ gender-typed traits. Sex Roles, 90(12), 1866–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Males | Females | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traits and Facets | Skewness | Kurtosis | M | SD | M | SD | p |

| Total score of masculinity | −0.20 | 0.73 | 5.07 | 0.97 | 4.59 | 0.02 | 0.000 |

| masculine | −0.49 | −0.73 | 5.49 | 1.33 | 3.44 | 1.70 | 0.000 |

| dominant | −0.41 | −0.17 | 4.83 | 1.45 | 4.23 | 1.47 | 0.000 |

| adventurous | −0.28 | −0.70 | 4.75 | 1.67 | 4.27 | 1.66 | 0.000 |

| with leadership | −0.18 | −0.42 | 4.37 | 1.57 | 4.24 | 1.47 | 0.130 |

| having supervisory abilities | −0.22 | −0.42 | 4.36 | 1.58 | 4.29 | 1.47 | 0.447 |

| unconstrained | −0.42 | −0.38 | 4.88 | 1.48 | 4.51 | 1.56 | 0.000 |

| bold | −0.30 | −0.52 | 4.81 | 1.52 | 4.32 | 1.52 | 0.000 |

| judicious | −0.72 | 0.90 | 5.37 | 1.22 | 5.00 | 1.24 | 0.000 |

| steady | −0.37 | −0.17 | 5.14 | 1.36 | 4.55 | 1.36 | 0.000 |

| brave | −0.43 | −0.08 | 5.19 | 1.37 | 4.63 | 1.37 | 0.000 |

| rational | −0.61 | 0.07 | 5.56 | 1.23 | 4.92 | 1.38 | 0.000 |

| calm | −0.58 | 0.22 | 5.39 | 1.25 | 4.83 | 1.39 | 0.000 |

| generous | −0.63 | 0.51 | 5.38 | 1.26 | 5.15 | 1.27 | 0.001 |

| capable of organizing | −0.35 | −0.22 | 4.62 | 1.54 | 4.62 | 1.38 | 0.957 |

| broad minded | −0.75 | 0.65 | 5.50 | 1.25 | 5.20 | 1.30 | 0.000 |

| magnanimous | −0.75 | 0.56 | 5.50 | 1.27 | 5.21 | 1.32 | 0.000 |

| Total score of femininity | −0.38 | 0.69 | 4.73 | 0.98 | 5.04 | 1.00 | 0.000 |

| tender | −0.56 | −0.11 | 5.07 | 1.51 | 4.87 | 1.51 | 0.020 |

| yielding | −0.27 | −0.61 | 4.50 | 1.65 | 4.36 | 1.69 | 0.146 |

| elegant | −0.21 | −0.48 | 4.47 | 1.59 | 4.51 | 1.49 | 0.630 |

| thoughtful | −0.81 | 0.77 | 5.34 | 1.36 | 5.48 | 1.22 | 0.050 |

| comforting | −0.74 | 0.03 | 5.04 | 1.58 | 5.31 | 1.46 | 0.002 |

| soft spoken | −0.29 | −0.37 | 4.54 | 1.55 | 4.66 | 1.52 | 0.172 |

| approachable | −0.55 | 0.08 | 4.82 | 1.46 | 5.19 | 1.38 | 0.000 |

| feminine | 0.35 | −1.22 | 1.81 | 1.32 | 4.63 | 1.53 | 0.000 |

| showing compassion | −1.11 | 1.37 | 5.47 | 1.42 | 5.79 | 1.18 | 0.000 |

| provident | −0.59 | 0.14 | 5.14 | 1.41 | 4.96 | 1.40 | 0.026 |

| gentle | −0.07 | −0.69 | 3.83 | 1.70 | 4.32 | 1.59 | 0.000 |

| careful | −0.21 | −0.57 | 4.31 | 1.57 | 4.57 | 1.57 | 0.003 |

| frugal | −0.47 | −0.01 | 4.90 | 1.43 | 4.81 | 1.42 | 0.279 |

| caring | −0.92 | 1.07 | 5.41 | 1.31 | 5.73 | 1.19 | 0.000 |

| understanding | −1.00 | 1.48 | 5.54 | 1.26 | 5.70 | 1.14 | 0.024 |

| good listener | −1.07 | 1.34 | 5.56 | 1.32 | 5.75 | 1.21 | 0.008 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, X.; Liu, W. Using Network Analysis to Identify Central Facets of Androgynous Development Between Sexes in Chinese Adolescents. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1375. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101375

Liu X, Liu W. Using Network Analysis to Identify Central Facets of Androgynous Development Between Sexes in Chinese Adolescents. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1375. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101375

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Xisha, and Weijun Liu. 2025. "Using Network Analysis to Identify Central Facets of Androgynous Development Between Sexes in Chinese Adolescents" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 10: 1375. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101375

APA StyleLiu, X., & Liu, W. (2025). Using Network Analysis to Identify Central Facets of Androgynous Development Between Sexes in Chinese Adolescents. Behavioral Sciences, 15(10), 1375. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101375