Dyadic Coping and Communication as Predictors of 10-Year Relationship Satisfaction Subgroup Trajectories in Stable Romantic Couples

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Changes in Relationship Satisfaction

1.2. Predictors of Changes in Relationship Satisfaction

1.3. Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Transparency and Openness

2.2. Participants and Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.4. Data Analyses

3. Results

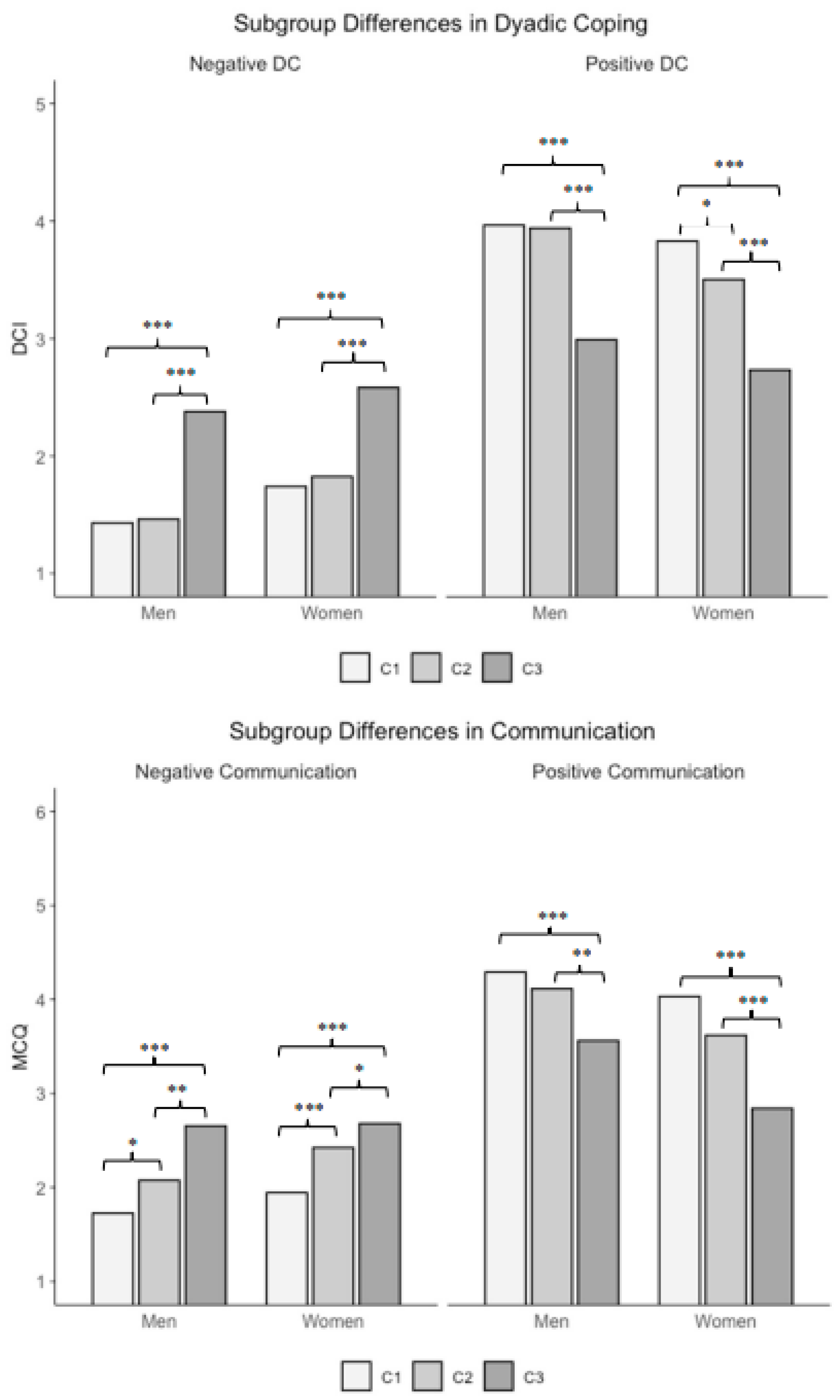

3.1. Positive and Negative Dyadic Coping

3.2. Positive and Negative Communication

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COM | Communication |

| DC | Dyadic Coping |

| DCI | Dyadic Coping Inventory |

| MCQ | Marital Communication Questionnaire |

References

- Algoe, S. B. (2019). Positive interpersonal processes. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 28(2), 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, E. S., Rhoades, G. K., Markman, H. J., & Stanley, S. C. (2015). PREP for strong bonds: A review of outcomes from a randomized clinical trial. Contemporary Family Therapy, 37(3), 232–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, P. R. (2000). The consequences of divorce for adults and children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(4), 1269–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J. R., Van Ryzin, M. J., & Doherty, W. J. (2010). Developmental trajectories of marital happiness in continuously married individuals: A group-based modeling approach. Journal of Family Psychology, 24(5), 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Be, D., Whisman, M. A., & Uebelacker, L. A. (2013). Prospective associations between marital adjustment and life satisfaction: Marital adjustment and life satisfaction. Personal Relationships, 20(4), 728–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, S. R. H., Katz, J., Kim, S., & Brody, G. H. (2003). Prospective effects of marital satisfaction on depressive symptoms in established marriages: A dyadic model. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 20(3), 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenman, G. (2008). Dyadisches coping inventar. Verlag Hans Huber, Hogrefe AG. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann, G. (1995). A systemic-transactional conceptualization of stress and coping in couples. Swiss Journal of Psychology/Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Psychologie/Revue Suisse de Psychologie, 54(1), 34–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann, G. (1997). Dyadic coping: A systemic-transactional view of stress and coping among couples: Theory and empirical findings. European Review of Applied Psychology, 47(2), 137–141. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann, G. (2000). Stress und Coping bei Paaren [Stress and coping in couples]. Hogrefe. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann, G. (2005). Dyadic coping and its significance for marital functioning. In T. A. Revenson, K. Kayser, & G. Bodenmann (Eds.), Couples coping with stress: Emerging perspectives on dyadic coping (1st ed. Aufl., S. 33–49). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann, G. (2008). Dyadic coping and the significance of this concept for prevention and therapy. Zeitschrift für Gesundheitspsychologie, 16(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenmann, G., Bradbury, T. N., & Pihet, S. (2009). Relative contributions of treatment-related changes in communication skills and dyadic coping skills to the longitudinal course of marriage in the framework of marital distress prevention. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 50(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenmann, G., Pihet, S., & Kayser, K. (2006). The relationship between dyadic coping and marital quality: A 2-year longitudinal study. Journal of Family Psychology, 20(3), 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenmann, G., & Shantinath, S. D. (2004). The Couples Coping Enhancement Training (CCET): A new approach to prevention of marital distress based upon stress and coping. Family Relations, 53(5), 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolck, A., Croon, M., & Hagenaars, J. (2004). Estimating latent structure models with categorical variables: One-step versus three-step estimators. Political Analysis, 12(1), 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. (1980). Attachment and loss. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bühler, J. L., Krauss, S., & Orth, U. (2021). Development of relationship satisfaction across the life span: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 147(10), 1012–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Don, B. P., & Mickelson, K. D. (2014). Relationship satisfaction trajectories across the transition to parenthood among low-risk parents: Relationship satisfaction trajectories. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76(3), 677–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doss, B. D., Simpson, L. E., & Christensen, A. (2004). Why do couples seek marital therapy? Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 35(6), 608–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, D., Derks, D., & Bakker, A. B. (2018). Daily spillover from family to work: A test of the work–home resources model. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(2), 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falconier, M. K., Jackson, J. B., Hilpert, P., & Bodenmann, G. (2015). Dyadic coping and relationship satisfaction: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 42, 28–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottman, J. M. (1994). What predicts divorce? Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, D. N., & Booth, A. (2005). Unhappily ever after: Effects of long-term, low-quality marriages on well-being. Social Forces, 84(1), 451–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(3), 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huston, T. L., Caughlin, J. P., Houts, R. M., Smith, S. E., & George, L. J. (2001). The connubial crucible: Newlywed years as predictors of marital delight, distress, and divorce. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(2), 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huston, T. L., & Houts, R. M. (1998). The psychological infrastructure of courtship and marriage: The role of personality and compatibility in romantic relationships. In T. N. Bradbury (Ed.), The developmental course of marital dysfunction (pp. 114–151). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joel, S., Eastwick, P. W., Allison, C. J., Arriaga, X. B., Baker, Z. G., Bar-Kalifa, E., Bergeron, S., Birnbaum, G. E., Brock, R. L., Brumbaugh, C. C., Carmichael, C. L., Chen, S., Clarke, J., Cobb, R. J., Coolsen, M. K., Davis, J., de Jong, D. C., Debrot, A., DeHaas, E. C., … Wolf, S. (2020). Machine learning uncovers the most robust self-report predictors of relationship quality across 43 longitudinal couples studies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(32), 19061–19071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, D. R., Amoloza, T. O., & Booth, A. (1992). Stability and developmental change in marital quality: A three-wave panel analysis. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 54(3), 582–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. D., Lavner, J. A., Mund, M., Zemp, M., Stanley, S. M., Neyer, F. J., Impett, E. A., Rhoades, G. K., Bodenmann, G., Weidmann, R., Bühler, J. L., Burriss, R. P., Wünsche, J., & Grob, A. (2022). Within-couple associations between communication and relationship satisfaction over time. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 48(4), 534–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joiner, R. J., Bradbury, T. N., Lavner, J. A., Meltzer, A. L., McNulty, J. K., Neff, L. A., & Karney, B. R. (2024). Are changes in marital satisfaction sustained and steady, or sporadic and dramatic? American Psychologist, 79(2), 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanter, J. B., Lannin, D. G., Rauer, A. J., & Yazedjian, A. (2023). Relational concerns and change in relationship satisfaction in a relationship education program. Family Process, 62(2), 576–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanter, J. B., Lavner, J. A., Lannin, D. G., Hilgard, J., & Monk, J. K. (2021). Does couple communication predict later relationship quality and dissolution? A meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family, 84(2), 533–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanter, J. B., & Proulx, C. M. (2021). Understanding the early years of socioeconomically disadvantaged couples’ marriages. Family Process, 60(3), 806–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karney, B. R., & Bradbury, T. N. (1995). The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: A review of theory, methods, and research. Psychological Bulletin, 118(1), 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karney, B. R., & Bradbury, T. N. (1997). Neuroticism, marital interaction, and the trajectory of marital satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72(5), 1075–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karney, B. R., & Bradbury, T. N. (2020). Research on marital satisfaction and stability in the 2010s: Challenging conventional wisdom. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 100–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurdek, L. A. (1998). The nature and predictors of the trajectory of change in marital quality over the first 4 years of marriage for first-married husbands and wives. Journal of Family Psychology, 12(4), 494–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurdek, L. A. (1999). The nature and predictors of the trajectory of change in marital quality for husbands and wives over the first 10 years of marriage. Developmental Psychology, 35(5), 1283–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavner, J. A., & Bradbury, T. N. (2010). Patterns of change in marital satisfaction over the newlywed years. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(5), 1171–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, R. J. A. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83(404), 1198–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNulty, J. K., Meltzer, A. L., Neff, L. A., & Karney, B. R. (2021). How both partners’ individual differences, stress, and behavior predict change in relationship satisfaction: Extending the VSA model. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(27), e2101402118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNulty, J. K., & Overall, N. C. (2025). Conflict in couple relationships. In N. C. Overall, J. A. Simpson, & J. A. Lavner (Eds.), Research handbook on couple and family relationships (pp. 202–217). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- McNulty, J. K., & Russell, V. M. (2010). When “negative” behaviors are positive: A contextual analysis of the long-term effects of problem-solving behaviors on changes in relationship satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(4), 587–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2017). Mplus user’s guide. Eighth Edition. Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Nagin, D. S. (1999). Analyzing developmental trajectories: A semiparametric, group-based approach. Psychological Methods, 4(2), 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagin, D. S. (2005). Group-based modeling of development. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbeck, F., Hilpert, P., & Bodenmann, G. (2012). The association between positive and negative interaction behavior with relationship satisfaction and the intention to separate in married couples. Journal of Family Research, 24(1), 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proulx, C. M., Ermer, A. E., & Kanter, J. B. (2017). Group-based trajectory modeling of marital quality: A critical review. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 9(3), 307–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proulx, C. M., Helms, H. M., & Buehler, C. (2007). Marital quality and personal well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(3), 576–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, A. K., & Bodenmann, G. (2009). The role of stress on close relationships and marital satisfaction. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(2), 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, A. K., Donato, S., Neff, L. A., Totenhagen, C. J., Bodenmann, G., & Falconier, M. (2022). A scoping review on couples’ stress and coping literature: Recognizing the need for inclusivity. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 40(3), 812–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2023). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statis-tical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Righetti, F., Faure, R., Zoppolat, G., Meltzer, A., & McNulty, J. (2022). Factors that contribute to the maintenance or decline of relationship satisfaction. Nature Reviews Psychology, 1(3), 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, T. F., Slatcher, R. B., Trombello, J. M., & McGinn, M. M. (2014). Marital quality and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 140(1), 140–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogge, R. D., Cobb, R. J., Lawrence, E., Johnson, M. D., & Bradbury, T. N. (2013). Is skills training necessary for the primary prevention of marital distress and dissolution? A 3-year experimental study of three interventions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(6), 949–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, M., Landolt, S. A., Nussbeck, F. W., Weitkamp, K., & Bodenmann, G. (2025). Positive outcomes of long-term relationship satisfaction trajectories in stable romantic couples: A 10-year longitudinal study. International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology, 10(1), 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffieux, M., Nussbeck, F. W., & Bodenmann, G. (2014). Long-term prediction of relationship satisfaction and stability by stress, coping, communication, and well-being. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 55(6), 485–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, P. P., Nussbeck, F. W., Leuchtmann, L., & Bodenmann, G. (2020). Stress, dyadic coping, and relationship satisfaction: A longitudinal study disentangling timely stable from yearly fluctuations. PLoS ONE, 15(4), e0231133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowan-Basheer, W. (2020). The effect of gender on negative emotional experiences accompanying Muslims’ and Jews’ use of verbal aggression in heterosexual intimate-partner relationships. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 29(3), 332–347. [Google Scholar]

- Stadelmann, C. (2022). From two to three—Families in the transition to parenthood [Doctoral thesis, University of Zurich]. [Google Scholar]

- Su, T., Ledermann, T., & Fincham, F. (2023). Does covenant marriage predict latent trajectory groups of newlywed couples? Personal Relationships, 30(1), 278–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmons, A. C., Arbel, R., & Margolin, G. (2017). Daily patterns of stress and conflict in couples: Associations with marital aggression and family-of-origin aggression. Journal of Family Psychology, 31(1), 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trail, T. E., & Karney, B. R. (2012). What’s (not) wrong with low-income marriages. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, H. C., Altman, N., Hsueh, J., & Bradbury, T. N. (2016). Effects of relationship education on couple communication and satisfaction: A randomized controlled trial with low-income couples. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(2), 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, R. G., Moore, Q., Clarkwest, A., & Killewald, A. (2014). The long-term effects of building strong families: A program for unmarried parents. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76(2), 446–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodin, E. M. (2011). A two-dimensional approach to relationship conflict: Meta-analytic findings. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(3), 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Subgroups | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Parameter | C1: High Relatively Stable n = 194 (65%) | C2: High Declining n = 56 (19%) | C3: Low Increasing n = 50 (17%) |

| Intercept women | 5.463 *** (0.125 ***) | 5.170 *** (0.414 ***) | 4.378 *** (0.551 ***) |

| Slope women | −0.022 *** | −0.144 *** | 0.032 * |

| Intercept men | 5.475 *** (0.114 ***) | 5.232 *** (0.261 ***) | 4.304 *** (0.382 **) |

| Slope men | −0.013 | −0.121 *** | 0.044 ** |

| Women | Men | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M (SD) | M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 1. | Rel Sat T1 | 5.20 (0.67) | 5.20 (0.69) | 0.56 | 0.49 | 0.55 | −0.48 | 0.47 | −0.47 |

| 2. | Rel Sat T10 | 4.90 (0.91) | 5.10 (0.74) | 0.47 | 0.59 | 0.34 | −0.27 | 0.32 | −0.33 |

| 3. | Pos DC T1 | 3.59 (0.78) | 3.80 (0.66) | 0.54 | 0.23 | 0.31 | −0.58 | 0.66 | −0.46 |

| 4. | Neg DC T1 | 1.90 (0.77) | 1.59 (0.60) | −0.51 | −0.34 | −0.48 | 0.36 | −0.47 | 0.53 |

| 5. | Pos COM T1 | 3.75 (0.94) | 4.16 (0.84) | 0.37 | 0.33 | 0.52 | −0.38 | 0.21 | −0.50 |

| 6. | Neg COM T1 | 2.15 (0.65) | 1.91 (0.61) | −0.51 | −0.27 | −0.45 | 0.54 | −0.45 | 0.51 |

| Positive DC | Positive DC Δ | Negative DC | Negative DC Δ | Positive COM | Positive COM Δ | Negative COM | Negative COM Δ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women M (SE) | ||||||||

| C1 | 3.829 (0.057) | −0.041 (0.085) p = 1.00 | 1.739 (0.059) | −0.105 (0.073) p = 0.52 | 3.995 (0.072) | −0.835 (0.160) p < 0.001 | 1.929 (0.047) | 0.037 (0.088) p = 1.00 |

| C2 | 3.503 (0.123) | −0.769 (0.156) p < 0.001 | 1.824 (0.120) | 0.596 (0.146) p < 0.001 | 3.706 (0.152) | −0.684 (0.284) p = 0.10 | 2.378 (0.107) | 0.298 (0.225) p = 0.56 |

| C3 | 2.732 (0.137) | 0.381 (0.196) p = 0.23 | 2.582 (0.130) | −0.662 (0.173) p < 0.001 | 2.827 (0.144) | −0.245 (0.298) p = 1.00 | 2.755 (0.118) | −0.583 (0.219) p = 0.06 |

| Equality | C1 vs. C2 p = 0.22 | C1 vs. C2 p < 0.001 | C1 vs. C2 p = 1.00 | C1 vs. C2 p < 0.001 | C1 vs. C2 p = 0.72 | C1 vs. C2 p = 1.00 | C1 vs. C2 p < 0.001 | C1 vs. C2 p = 1.00 |

| tests | C1 vs. C3 p < 0.001 | C1 vs. C3 p = 0.46 | C1 vs. C3 p < 0.001 | C1 vs. C3 p = 0.06 | C1 vs. C3 p < 0.001 | C1 vs. C3 p = 0.68 | C1 vs. C3 p < 0.001 | C1 vs. C3 p = 0.13 |

| C2 vs. C3 p < 0.001 | C2 vs. C3 p < 0.001 | C2 vs. C3 p < 0.001 | C2 vs. C3 p < 0.001 | C2 vs. C3 p < 0.001 | C2 vs. C3 p = 1.00 | C2 vs. C3 p = 0.21 | C2 vs. C3 p = 0.07 | |

| Men M (SE) | ||||||||

| C1 | 3.965 (0.048) | 0.038 (0.077) p = 0.21 | 1.429 (0.042) | 0.034 (0.055) p = 1.0 | 4.330 (0.067) | −0.920 (0.180) p < 0.001 | 1.698 (0.039) | 0.210 (0.079) p = 0.06 |

| C2 | 3.940 (0.083) | −0.481 (0.124) p < 0.001 | 1.461 (0.079) | 0.385 (0.141) p = 0.05 | 4.101 (0.136) | −0.642 (0.326) p = 0.23 | 1.979 (0.101) | 0.471 (0.203) p = 0.12 |

| C3 | 2.990 (0.136) | −0.117 (0.152) p = 1.00 | 2.378 (0.114) | −0.417 (0.147) p = 0.05 | 3.562 (0.121) | −0.793 (0.309) p = 0.07 | 2.683 (0.141) | −0.463 (0.224) p = 0.21 |

| Equality | C1 vs. C2 p = 1.00 | C1 vs. C2 p = 0.001 | C1 vs. C2 p = 1.00 | C1 vs. C2 p = 0.26 | C1 vs. C2 p = 0.95 | C1 vs. C2 p = 1.00 | C1 vs. C2 p = 0.14 | C1 vs. C2 p = 1.00 |

| tests | C1 vs. C3 p < 0.001 | C1 vs. C3 p = 1.00 | C1 vs. C3 p < 0.001 | C1 vs. C3 p = 0.07 | C1 vs. C3 p < 0.001 | C1 vs. C3 p = 1.00 | C1 vs. C3 p < 0.001 | C1 vs. C3 p = 0.08 |

| C2 vs. C3 p < 0.001 | C2 vs. C3 p = 0.54 | C2 vs. C3 p < 0.001 | C2 vs. C3 p < 0.001 | C2 vs. C3 p = 0.05 | C2 vs. C3 p = 1.00 | C2 vs. C3 p < 0.001 | C2 vs. C3 p = 0.04 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roth, M.; Nussbeck, F.W.; Landolt, S.A.; Senn, M.; Bradbury, T.N.; Weitkamp, K.; Bodenmann, G. Dyadic Coping and Communication as Predictors of 10-Year Relationship Satisfaction Subgroup Trajectories in Stable Romantic Couples. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1361. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101361

Roth M, Nussbeck FW, Landolt SA, Senn M, Bradbury TN, Weitkamp K, Bodenmann G. Dyadic Coping and Communication as Predictors of 10-Year Relationship Satisfaction Subgroup Trajectories in Stable Romantic Couples. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1361. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101361

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoth, Michelle, Fridtjof W. Nussbeck, Selina A. Landolt, Mirjam Senn, Thomas N. Bradbury, Katharina Weitkamp, and Guy Bodenmann. 2025. "Dyadic Coping and Communication as Predictors of 10-Year Relationship Satisfaction Subgroup Trajectories in Stable Romantic Couples" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 10: 1361. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101361

APA StyleRoth, M., Nussbeck, F. W., Landolt, S. A., Senn, M., Bradbury, T. N., Weitkamp, K., & Bodenmann, G. (2025). Dyadic Coping and Communication as Predictors of 10-Year Relationship Satisfaction Subgroup Trajectories in Stable Romantic Couples. Behavioral Sciences, 15(10), 1361. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101361