Engagement by Design: Belongingness, Cultural Value Orientations, and Pathways into Emerging Technologies

Abstract

1. Introduction

Cultural Value Orientations: Beyond the Individualism–Collectivism Dichotomy

2. Technology Engagement Across Cultural Value Orientations

- Expert-sanctioned learning and hierarchical competence development: VC cultures across Asia and Asian diaspora demonstrate learning traditions characterized by what J. Li (2012) calls a “virtue orientation” towards knowledge acquisition. This approach emphasizes methodical and persistent knowledge and skill development through disciplined pathways, respect for established expertise hierarchies, and structured progression. It would be feasible to argue that VC shapes technology integration by positioning technologies within hierarchical frameworks, where both technologies and learners occupy defined roles. The emphasis on comprehensive mastery and progression creates a natural alignment with design and algorithms in technological landscape, which similarly requires hierarchical knowledge structures. Individuals from these contexts develop cognitive frameworks emphasizing structured and integrated problem-solving (R. E. Nisbett et al., 2001), facilitating the precise rule application central to technology domains like programming, algorithms, and systems design. This alignment helps explain the strong representation of individuals from VC cultures in technology fields.

- Role-based integration: As noted above, technologies are positioned within existing hierarchical role structures, with clear expectations about their functions and limitations. This also creates cognitive comfort with technologies as specialized contributors within existing social structures (Kim & Sherman, 2007). This orderly approach to defining relationships between components, thus, directly parallels programming paradigms, database design, and systems architecture, all of which depend on precisely organized hierarchical structures and clear role definitions.

- Convergent cognitive patterns: VC cultures foster distinctive thinking styles that particularly benefit certain technology domains. As R. E. Nisbett et al. (2001) argued, cognitive traditions in these cultures prioritize fluency in convergent thinking, attention to structural relationships, and systematic categorization. Incidentally, these are all features applicable to technology design, systems architecture, and structured problem-solving approaches directly relevant to technology engagement, including Computational Thinking. Unlike more divergent thinking patterns that prioritize novel connections or contextual flexibility, these convergent cognitive approaches excel in domains requiring precise rule application, logical consistency, and systematic analysis, which are all skills highly valued in many traditional technology engagement pathways. It should be emphasized here that, while the framework discusses tendencies towards convergent and/or divergent cognitive patterns, successful technology engagement typically requires a dynamic interplay of both convergent (structured, synthesizing, and rule-based) and divergent (creative, oft-spontaneous, and contextual) thinking. Therefore, the current goal is to highlight cultural emphases in engagement modes, including the flexibility to navigate between convergent and divergent thinking patterns as appropriate, and not to imply fixed cognitive limitations or exclusive capacities across groups.

- Community-validated adoption: Technology adoption tends to spread through peer-and-community endorsement, rather than hierarchical channels such as formal education, in HC. This may create resistance to technologies perceived as imposed by external authorities without community validation (Cuban, 2003). Research by Moll et al. (2005) demonstrates how emerging technology adoption in HC communities often follows network-based diffusion patterns where trusted community leaders or members serve as innovation brokers and cultural translators. These adoption patterns create powerful authentic engagement when technologies resonate with community values but can create barriers when educational institutions fail to recognize or leverage these community-based validation processes. Unlike the hierarchical adoption characteristic of VC contexts described earlier, HC communities often develop sophisticated grassroots evaluation systems that prioritize community relevance over institutional endorsement, which is a process that educational systems frequently overlook or misinterpret as resistance rather than alternative validation.

- Relationship-enhancing integration: Technologies tend to be valued in HC for their ability to strengthen community connections rather than establish specialized roles or tasks. Technology that ignores relational dimensions may therefore face resistance in HC (Collins, 2009). Research by Nasir and Hand (2008) illustrates how technology engagement in HC communities is frequently embedded within rich social contexts where the development of technological competence serves community relationships rather than existing as an independent pursuit. This orientation manifests in collaborative approaches to technology learning, where knowledge sharing becomes a form of social capital and technological expertise is valued for its contribution to collective endeavors. Unlike the role-specialization frameworks common in VC contexts, HC approaches often emphasize distributed expertise and reciprocal teaching relationships, where expertise is recognized but not hierarchically privileged in ways that might disrupt community equality.

- Social equity emphasis: Research suggests that modern technologies are evaluated based on their contribution to advancing community welfare and addressing inequities in HC, as follows. Learners may disengage from technologies perceived as perpetuating rather than rectifying social inequalities (Scott et al., 2013). Further, Barton and Tan (2010) demonstrate how HC-oriented communities evaluate technological innovations through their potential to enhance community sovereignty and address historical inequities. This evaluative lens fundamentally shapes engagement with STEM fields, as learners assess whether technological pathways offer meaningful opportunities to address community challenges or merely reproduce existing power structures. Unlike the competence-focused evaluation criteria common in VC contexts, HC communities often apply what Eglash et al. (2013) point out as culturally relative criteria that emphasize how technologies might preserve cultural heritage while creating new opportunities for community advancement.

3. Implications for Addressing Technology Achievement Gaps

4. Discussion and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barton, A. C., & Tan, E. (2010). We be burnin’! Agency, identity, and science learning. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 19(2), 187–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, D. T., Gale, A., Quinn, C. R., Mueller-Williams, A. C., Jones, K. V., Williams, E., & Lateef, H. A. (2024). Do we belong? Examining the associations between adolescents’ perceptions of school belonging, teacher discrimination, peer prejudice and suicide. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 11(3), 1454–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calaza, K. C., Erthal, F. C. S., Pereira, M. G., Macario, K. C. D., Daflon, V. T., David, I. P. A., Castro, H. C., Vargas, M. D., Martins, L. B., Stariolo, J. B., Volchan, E., & de Oliveira, L. (2021). Facing racism and sexism in science by fighting against social implicit bias: A latina and black woman’s perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 671481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, P., Auchstetter, A., Lin, S., & Savage, C. (2022). CompuPower investing in innovation evaluation: Final report. American Institutes for Research. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, P. H. (2009). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cuban, L. (2003). Oversold and underused: Computers in the classroom. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Darling-Hammond, L. (2010). The flat world and education: How America’s commitment to equity will determine our future. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dixson, A. D., & Rousseau Anderson, C. (2018). Where are we? Critical race theory in education 20 years later. Peabody Journal of Education, 93(1), 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eglash, R., Gilbert, J. E., Taylor, V., Geier, S. R., Clark, K., & Scott, K. A. (2013). Culturally responsive computing in urban, after-school contexts: Two approaches. Urban Education, 48(5), 629–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, R., Kennedy, B., & Funk, C. (2021). STEM jobs see uneven progress in increasing gender, racial and ethnic diversity. Pew Research. [Google Scholar]

- Godwin, A., Perkins, H., DeAngelo, L., McChesney, E., Kaufman-Ortiz, K., Dorve-Lewis, G., & Conrique, B. (2024). Belonging in engineering for black, Latinx, and indigenous students: Promising results from an educational intervention in an introductory programming course. IEEE Transactions on Education, 67(1), 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, C., Rattan, A., & Dweck, C. S. (2012). Why do women opt out? Sense of belonging and women’s representation in mathematics. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(4), 700–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalan, M., & Brady, S. T. (2020). College students’ sense of belonging: A national perspective. Educational Researcher, 49(2), 134–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouvea, J. S. (2021). Antiracism and the problems with “achievement gaps” in STEM education. Life Sciences Education, 20(1), fe2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton-Marcell, J., Bryson, T., Larson, J., Childers, T., Pasero, S., Watkins, C., Reed, T., Flucas-Payton, D., & Papka, M. E. (2023). Leveraging national laboratories to increase Black representation in STEM: Recommendations within the Department of Energy. International Journal of STEM Education, 10(1), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, M. (2023). The underrepresentation of women in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) leadership positions. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, B. (2023). Poverty highest for black, Asian Chicagoans; lower for white, Hispanic residents, Poverty highest for Black, Asian Chicagoans; lower for white, Hispanic residents. Illinois Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture and organizations. International Studies of Management & Organization, 10(4), 15–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornik, S., & Tupchiy, A. (2006). Culture’s impact on technology mediated learning: The role of horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism. Journal of Global Information Management, 14(4), 31–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsin, A., & Xie, Y. (2014). Explaining Asian Americans’ academic advantage over whites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences—PNAS, 111(23), 8416–8421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M. Y. (2015). The good immigrants: How the yellow peril became the model minority, pilot project. eBook available to selected US libraries only. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, M., Kho, C., Main, A., & Zawadzki, M. J. (2021). Horizontal collectivism moderates the relationship between in-the-moment social connections and well-being among Latino/a college students. The Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 23(5), 1001–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. S., & Sherman, D. K. (2007). “Express yourself”: Culture and the effect of self-expression on choice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komarraju, M., & Cokley, K. O. (2008). Horizontal and vertical dimensions of individualism-collectivism: A comparison of African Americans and European Americans. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 14(4), 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladson-Billings, G., & TateIv, W. F. (1995). Toward a critical race theory of education. Teachers College Record, 97(1), 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, C. M., Shah, N., & Falkner, K. (2019). Equity and diversity. In S. A. Fincher, & A. V. Robins (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of computing education research (pp. 481–510). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G., Tian, Z., & Hong, H. (2023). Language education of Asian migrant students in North America. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. (2012). Cultural foundations of learning: East and West (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J., Xue, E., Zhou, W., Guo, S., & Zheng, Y. (2025). Students’ subjective well-being, school bullying, and belonging during the COVID-19 pandemic: Comparison between PISA 2018 and PISA 2022. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 12(1), 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, X., Chen, Y., Zhao, S., & Zheng, D. (2025). What do we know: Positive impact of hip-hop pedagogy on student’s learning effects. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 6, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, M., Gonzalez-Barrera, A., & Patten, E. (2013). Closing the digital divide: Latinos and technology adoption. Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/race-and-ethnicity/2013/03/07/closing-the-digital-divide-latinos-and-technology-adoption/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Mallinson, C. (2024). Linguistic variation and linguistic inclusion in the US educational context. Annual Review of Linguistics, 10, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll, L., Amanti, C., Neff, D., González, N., Moll, L. C., González, N., & Amanti, C. (2005). Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms (1st ed., pp. 71–87). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, C., Travaglino, G. A., & Uskul, A. K. (2018). Social value orientation and endorsement of horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism: An exploratory study comparing individuals from North America and South Korea. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasir, N. S., & Hand, V. (2008). From the court to the classroom: Opportunities for engagement, learning, and identity in basketball and classroom mathematics. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 17(2), 143–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbett, R. (2004). The geography of thought: How Asians and westerners think differently…and why. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nisbett, R. E., Peng, K., Choi, I., & Norenzayan, A. (2001). Culture and systems of thought: Holistic versus analytic cognition. Psychological Review, 108(2), 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, M. (2004). Treatment of Japanese-American internment during World War II in U.S. history textbooks. International Journal of Social Education, 19(1), 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, K. A., White, M. A., Clark, K., & Scott, K. A. (2013). COMPUGIRLS’ standpoint: Culturally responsive computing and its effect on girls of color. Urban Education, 48(5), 657–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servant-Miklos, V. F. C. (2019). Fifty years on: A retrospective on the world’s first problem-based learning programme at McMaster university medical school. Health Professions Education, 5(1), 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P., Kumi-Yeboah, A., Chang, R., Lee, J., & Frazier, P. (2019). Rethinking “(under) performance” for black English speakers. Journal of Black Studies, 50(6), 528–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, V. (2018). Asian Americans are falling through the cracks in data representation and social services. Urban Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Triandis, H. C., & Gelfand, M. J. (1998). Converging measurement of horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(1), 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, J. H., & Kemmelmeier, M. (2013). Ethnicity and contemporary American culture: A meta-analytic investigation of horizontal–vertical individualism–collectivism. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44(2), 195–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, R. (2023). Being Asian American women scientists and engineers in the United States: Intersection of ethnicity and gender. The American Behavioral Scientist, 67(9), 1139–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez-Ibáñez, C. G., & Greenberg, J. B. (1992). Formation and transformation of funds of knowledge among U.S.-Mexican households. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 23(4), 313–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, G. M., & Cohen, G. L. (2007). A question of belonging: Race, social fit, and achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(1), 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, S. C., Samuel, C., Cho, A., Lombana-Bermudez, A., Shaw, V., Vickery, J. R., & Weinzimmer, L. (2018). The digital edge how Black and Latino youth navigate digital inequality. New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Whitacre, P., Laurencin, C. T., Malcom, S., Pinn, V., & Hammonds, E. (2023a). Reality-based observations from those on the pathway. In Psychological factors that contribute to the dearth of Black students in science, engineering, and medicine: Proceedings of a workshop (pp. 57–62). National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Whitacre, P., Laurencin, C. T., Pinn, V., Hammonds, E., & Malcom, S. (2023b). Introduction. In Psychological factors that contribute to the dearth of Black students in science, engineering, and medicine: Proceedings of a workshop (pp. 1–6). National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, S., Zhang, Y., Lu, Y., & Shadiev, R. (2024). Sense of belonging, academic self-efficacy and hardiness: Their impacts on student engagement in distance learning courses. British Journal of Educational Technology, 55(4), 1703–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M., Coloma, R. S., Sun, W., & Kwon, J. (2024). Dissecting Anti-Asian racism through a historical and transnational AsianCrit lens. Sociological Inquiry, 94(2), 330–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L. X., & Cheryan, S. (2017). Two axes of subordination: A new model of racial position. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 112(5), 696–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimensions | Vertical Collectivism (VC) | Horizontal Collectivism (HC) |

|---|---|---|

| Key Belongingness Pathway | Recognition vis-a-vis hierarchical structures through demonstrated expertise and structured achievements | Community integration through peer support, collective contribution, and mutual validation |

| Group Structure | Structured hierarchies with established roles that provide clear pathways to recognition | Flattened authority structures with distributed responsibilities that emphasize equality |

| Decision-making Process | Deference to established authority and expert figures validates belonging through expert acknowledgment | Consensus-building through community dialogue creates belonging through inclusive participation |

| Knowledge Transmission | Structured pathways following hierarchy of expertise create belonging through progressive mastery | Informal and lateral networks create belonging through reciprocal learning relationships |

| Individual–Group Relationship | Personal goals align with group goals within hierarchical framework, with belonging earned through role fulfilment | Personal goals align with group welfare, with belonging achieved through community contribution |

| Achievement Recognition | Formal recognition within established hierarchies validates technological competence and belonging | Community acknowledgment of contributions to collective welfare affirms belonging and value |

| Experiences That Promote Belonging | Expert validation, skill mastery acknowledgment, hierarchical advancement, structured milestone recognition | Community acceptance, peer affirmation, collective impact recognition, mutual support validation |

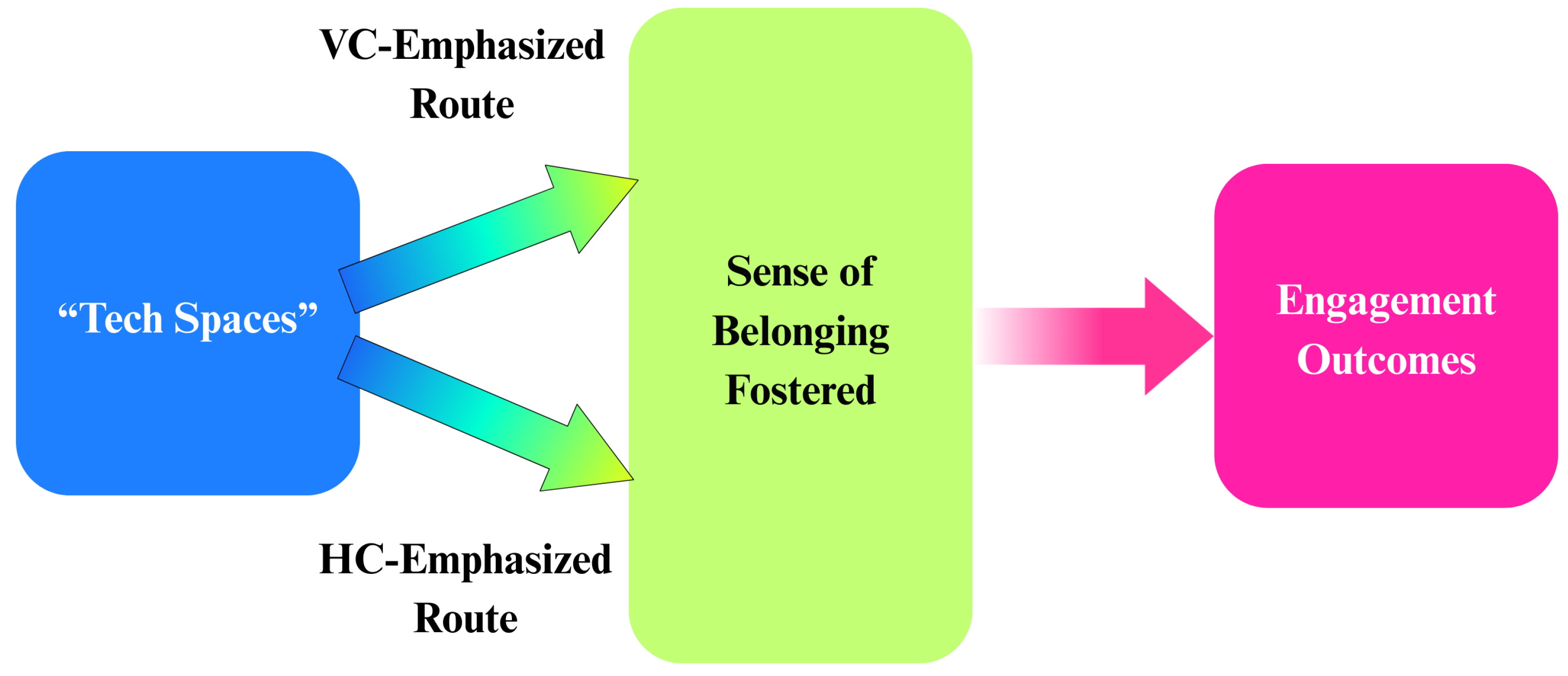

| Dimensions | Vertical Collectivism (VC)-Emphasized | Horizontal Collectivism (HC)-Emphasized |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Belongingness Strategy | Achieve belonging through expert validation of technological competence within established hierarchies | Achieve belonging through technology’s ability to foster community connections and advance collective welfare |

| Technology Positioning for Belongingness | Role- or task-based integration within existing hierarchical structures that include both humans and technology | Relationship-enhancing tools valued for their ability to build community bonds and solidarity |

| Learning Pathway to Belongingness | Expert-sanctioned, structured mastery progression that leads to expert recognition and hierarchical advancement | Community-validated adoption through peer networks that emphasizes shared experience and mutual learning |

| Cognitive Approach Supporting Belongingness | Convergent thinking emphasizing structural relationships and systematic categorization that aligns with the demands of the task at hand | Contextual thinking emphasizing social applications and community benefits that resonates with peer values |

| Evaluation Criteria for Belongingness | Technological proficiency and competence development measured against established standards | Social equity impact and community contribution measured through collective benefit and peer validation |

| Belongingness Validation Process | Expert-sanctioned learning through established hierarchies leading to formal recognition | Community-validated adoption through peer networks leading to collective endorsement |

| Observable Belongingness Outcomes | Systematic skill development, hierarchical role achievement, and expert acknowledgment | Enhanced community connections, collaborative innovations, collective problem-solving contributions |

| Design Element | To Foster Primarily VC-Emphasized Belongingness | To Foster Primarily HC-Emphasized Belongingness |

|---|---|---|

| Target Belongingness Experience | Experience authentic belonging through expert recognition of their technological competence and structured achievement within clear hierarchies | Experience authentic belonging through peer validation of their contributions to community-centered technological solutions |

| Instructional Structure for Belongingness | Progression with achievement milestones that provide clear pathways to expert recognition | Community-embedded projects addressing local issues that create opportunities for peer validation and collective impact |

| Expert Relations Supporting Belongingness | Clear expert–learner roles that validate learning through expert leadership and validation | Collaborative learning communities with distributed expertise that affirm belonging through peer recognition |

| Assessment Approaches for Belongingness | Competency-based evaluations aligned with industry standards that provide expert validation of technological mastery | Portfolio assessments showcasing community contributions that enable peer evaluation and collective validation |

| Motivational Framework for Belongingness | Recognition within established hierarchies through knowledge and skill achievement that fulfills their roles | Contribution to community wellbeing and social equity that demonstrates value through collective impact |

| Family/Community Integration for Belongingness | Parent education about educational pathways that validates family or community investment in achievement | Active family and community participation as co-designers that affirms cultural values in learning process |

| Technology Selection for Belongingness | Tools emphasizing systematic skill development that align with expert expectations and structured competence building | Technologies supporting communication, collaboration, and community problem- solving that enhance relational connections |

| Belongingness Success Indicators | Expert validation received, skill milestones achieved, hierarchical progression demonstrated, structured recognition obtained, etc. | Community acceptance gained, peer affirmation received, community impact achieved, mutual support relationships established, etc. |

| Level of Intervention | To Promote Vertical Collectivist (VC)- Aligned Belongingness | To Promote Horizontal Collectivist (HC)- Aligned Belongingness |

|---|---|---|

| Educational Policy | Hierarchical pathways with clear skill mastery milestones and recognition that enable expert validation and structured belonging | Community-based technology initiatives and flexible credentialing that affirm collective ownership and peer validation |

| Curriculum Design | Sequential skill development with explicit connections to established knowledge and skill hierarchies that foster belongingness through expert recognition and incremental mastery | Project-based learning addressing community challenges with direct community impact that foster belongingness through collective contributions |

| Teaching Methods | Expert-guided instruction that validates belong through incremental knowledge/skill mastery and authority acknowledgment | Collaborative learning communities with distributed expertise and peer mentoring that affirm belonging through mutual recognition |

| Assessment Approaches | Competency-based evaluations aligned with standards that provide expert validation and belonging confirmation | Portfolio assessments showcasing community contributions and collaborative achievements that enable peer validation and collective belong |

| Family Engagement | Family education about educational pathways and career trajectories that validates family investment in hierarchical achievement and belonging in technology | Active family participation as co-designers and contributors to learning experiences that affirms cultural values and community belonging |

| Technology Selection | Tools emphasizing systematic skill development and technological proficiency that align with expert expectations and structured belonging pathways | Technologies supporting communication, collaboration, and community problem-solving that enhance relational connections and collective belonging |

| Structural Support | Mentoring from experts that provide pathways to validation and hierarchical belonging | Community technology centers with local or institutional leadership and intergenerational programming that foster peer validation and collective belonging |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Akiba, D.; Perrone, M.; Almendral, C.; Garte, R. Engagement by Design: Belongingness, Cultural Value Orientations, and Pathways into Emerging Technologies. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1358. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101358

Akiba D, Perrone M, Almendral C, Garte R. Engagement by Design: Belongingness, Cultural Value Orientations, and Pathways into Emerging Technologies. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1358. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101358

Chicago/Turabian StyleAkiba, Daisuke, Michael Perrone, Caterina Almendral, and Rebecca Garte. 2025. "Engagement by Design: Belongingness, Cultural Value Orientations, and Pathways into Emerging Technologies" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 10: 1358. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101358

APA StyleAkiba, D., Perrone, M., Almendral, C., & Garte, R. (2025). Engagement by Design: Belongingness, Cultural Value Orientations, and Pathways into Emerging Technologies. Behavioral Sciences, 15(10), 1358. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101358