Improving Confidence and Self-Esteem Among Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Children: A Social Emotional Learning Intervention in Rural China

Abstract

1. Introduction

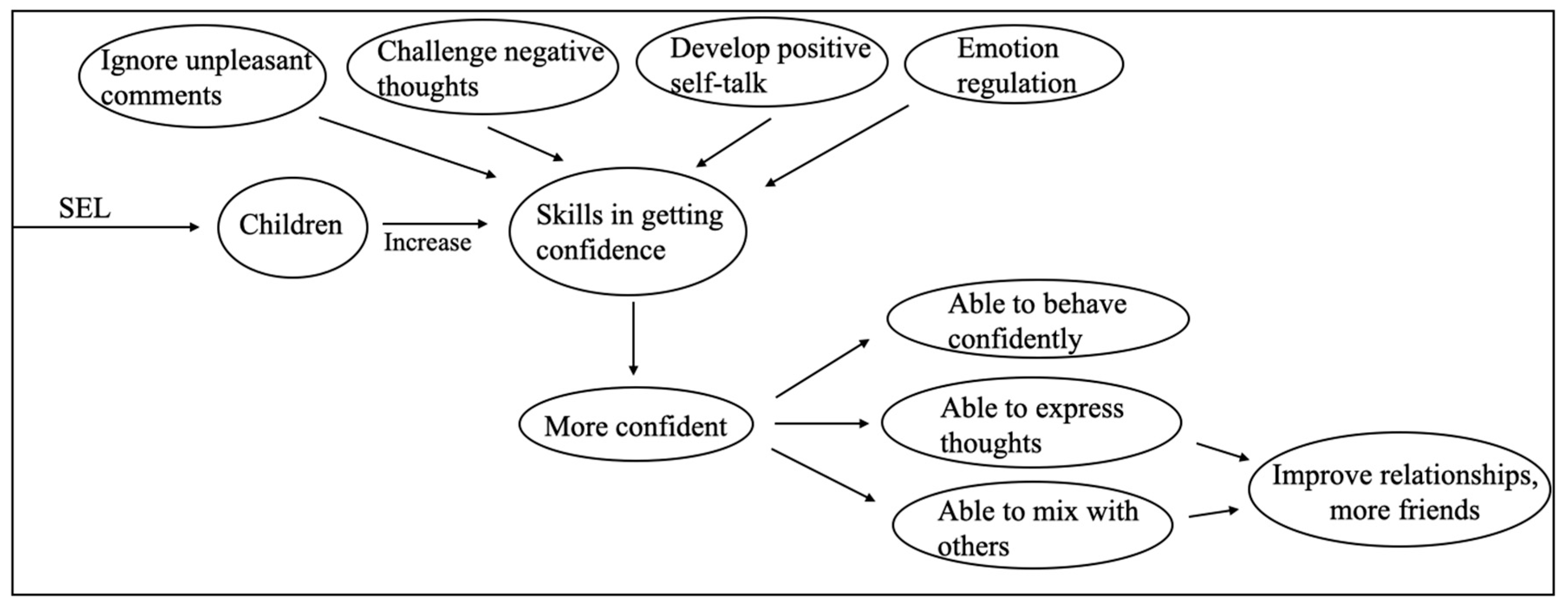

1.1. SEL-Based Interventions to Enhance Confidence and Self-Esteem

1.2. Cognitive Behavioral Approach in SEL-Based Interventions

1.3. SEL in Mainland China

1.4. The Strong Emphasis on Academic Achievement in China

1.5. The Necessity and Main Aims of the Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Intervention Implementation

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection and Measurements

2.4. Ethics

2.5. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and Background Information

3.2. The Scores of Self-Esteem and Self-Efficacy at Three Assessments

3.3. Intervention Effects on Self-Esteem and Self-Efficacy

3.4. Qualitative Interviews

4. Discussion

5. Implications for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SEL | Social and emotional learning |

| UNICEF | United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund |

| RSES | Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale |

| GSES | General self-efficacy scale |

| LMM | Linear mixed models |

References

- Ackerman, C. E. (2023). What is self-confidence? Available online: https://positivepsychology.com/self-confidence/ (accessed on 9 July 2018).

- Ahlen, J., Lenhard, F., & Ghaderi, A. (2019). Long-term outcome of a cluster-randomized universal prevention trial targeting anxiety and depression in school children. Behavior Therapy, 50(1), 200–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsandaux, J., Galéra, C., & Salamon, R. (2021). The association of self-esteem and psychosocial outcomes in young adults: A 10-year prospective study. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 26(2), 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W H Freeman/Times Books/Henry Holt & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, P., Lock, S., & Farrell, L. (2005). Developmental differences in universal preventive intervention for child anxiety. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 10(4), 539–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, P., & Turner, C. (2001). Prevention of anxiety symptoms in primary school children: Preliminary results from a universal school-based trial. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 40(4), 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, J. S., & Beck, A. T. (2011). Cognitive behavior therapy, second edition: Basics and beyond. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chui, W. H., & Wong, M. Y. H. (2017). Avoiding disappointment or fulfilling expectation: A study of gender, academic achievement, and family functioning among Hong Kong adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(1), 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, A. M., Bunting, B., & Barry, M. M. (2014). Evaluating the implementation of a school-based emotional well-being programme: A cluster randomized controlled trial of Zippy’s Friends for children in disadvantaged primary schools. Health Education Research, 29(5), 786–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, A. M., Sixsmith, J., & Barry, M. M. (2015). Evaluating the implementation of an emotional wellbeing programme for primary school children using participatory approaches. Health Education Journal, 74(5), 578–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, M., & Ross, M. (1984). Getting what you want by revising what you had. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47(4), 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jonge-Heesen, K. W. J., Rasing, S. P. A., Vermulst, A., Scholte, R., van Ettekoven, K. M., Engels, R., & Creemers, D. H. M. (2020). Randomized control trial testing the effectiveness of implemented depression prevention in high-risk adolescents. BMC Medicine, 18(1), 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinos, S., & Palmer, S. (2015). Self-esteem within cognitive behavioural coaching: A theoretical framework to integrate theory with practice. Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research & Practice, 8(2), 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, S., Fujiwara, T., Isumi, A., & Ochi, M. (2019). Pathway of the association between child poverty and low self-esteem: Results from a population-based study of adolescents in Japan. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domitrovich, C. E., Durlak, J. A., Staley, K. C., & Weissberg, R. P. (2017). Social-emotional competence: An essential factor for promoting positive adjustment and reducing risk in school children. Child Development, 88(2), 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epel, N., Zohar, A. A., Artom, A., Novak, A. M., & Lev-Ari, S. (2021). The effect of cognitive behavioral group therapy on children’s self-esteem. Children, 8(11), 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L., Zhang, Z., Yang, Y., & Curtis McMillen, J. (2024). Acceptability and preliminary impact of a school-based SEL program for rural children in China: A quasi-experimental study. Children and Youth Services Review, 160, 107579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanton, S., Mellalieu, S. D., & Hall, R. (2004). Self-confidence and anxiety interpretation: A qualitative investigation. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 5(4), 477–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, M.-S., Chung, H.-I. C., & Lee, Y.-J. (2005). The effect of cognitive–behavioral group therapy on the self-esteem, depression, and self-efficacy of runaway adolescents in a shelter in South Korea. Applied Nursing Research, 18(3), 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C., Zhu, Y., Luo, Y., Tan, C.-S., Mastrotheodoros, S., Costa, P., Chen, L., Guo, L., Ma, H., & Meng, R. (2023). Validation of the Chinese version of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: Evidence from a three-wave longitudinal study. BMC Psychology, 11(1), 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouvava, S., Antonopoulou, K., Zioga, S., & Karali, C. (2011). The influence of musical games and role-play activities upon primary school children’s self-concept and peer relationships. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 29, 1660–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuosmanen, T., Clarke, A. M., & Barry, M. M. (2019). Promoting adolescents’ mental health and wellbeing: Evidence synthesis. Journal of Public Mental Health, 18(1), 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laible, D. J., Carlo, G., & Roesch, S. C. (2004). Pathways to self-esteem in late adolescence: The role of parent and peer attachment, empathy, and social behaviours. Journal of Adolescence, 27(6), 703–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J., & Hesketh, T. (2023). A social emotional learning intervention to reduce psychosocial difficulties among rural children in central China. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 16, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry-Webster, H. M., Barrett, P. M., & Lock, S. (2003). A universal prevention trial of anxiety symptomology during childhood: Results at 1-year follow-up. Behaviour Change, 20(1), 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, S. L., Parker, P. D., Ciarrochi, J., & Heaven, P. C. L. (2014). Is self-esteem a cause or consequence of social support? A 4-year longitudinal study. Child Development, 85(3), 1275–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C. F., Kochel, K. P., Wheeler, L. A., Updegraff, K. A., Fabes, R. A., Martin, C. L., & Hanish, L. D. (2017). The efficacy of a relationship building intervention in 5th grade. Journal of School Psychology, 61, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2022). Households’ Income and Consumption Expenditure in 2021. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/english/PressRelease/202201/t20220118_1826649.html (accessed on 18 January 2022).

- Orth, U., & Robins, R. W. (2022). Is high self-esteem beneficial? Revisiting a classic question. American Psychologist, 77(1), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L., & Ye, J. (2017). “Children of great development”: Difficulties in the education and development of rural left-behind children. Chinese Education and Society, 50(4), 336–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romppel, M., Herrmann-Lingen, C., Wachter, R., Edelmann, F., Düngen, H. D., Pieske, B., & Grande, G. (2013). A short form of the General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE-6): Development, psychometric properties and validity in an intercultural non-clinical sample and a sample of patients at risk for heart failure. Psycho-Social Medicine, 10, Doc01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Journal of Religion and Health. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R., & Jerusalem, M. (1995). Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale. In J. Weinman, S. Wright, & M. Johnston (Eds.), Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio. Causal and control beliefs (Vol. 35, p. 82-003). NFER-NELSON. [Google Scholar]

- Sheffield, J. K., Spence, S. H., Rapee, R. M., Kowalenko, N., Wignall, A., Davis, A., & McLoone, J. (2006). Evaluation of universal, indicated, and combined cognitive-behavioral approaches to the prevention of depression among adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(1), 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverthorn, N., DuBois, D. L., Lewis, K. M., Reed, A., Bavarian, N., Day, J., Ji, P., Acock, A. C., Vuchinich, S., & Flay, B. R. (2017). Effects of a school-based social-emotional and character development program on self-esteem levels and processes: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. SAGE Open, 7(3), 215824401771323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sklad, M., Diekstra, R., Ritter, M. D., Ben, J., & Gravesteijn, C. (2012). Effectiveness of school-based universal social, emotional, and behavioral programs: Do they enhance students’ development in the area of skill, behavior, and adjustment? Psychology in the Schools, 49(9), 892–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skryabina, E., Morris, J., Byrne, D., Harkin, N., Rook, S., & Stallard, P. (2016). Child, teacher and parent perceptions of the FRIENDS classroom-based universal anxiety prevention programme: A qualitative study. School Mental Health, 8(4), 486–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowislo, J. F., & Orth, U. (2013). Does Low Self-esteem predict depression and anxiety? A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 139(1), 213–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiger, A. E., Allemand, M., Robins, R. W., & Fend, H. A. (2014). Low and decreasing self-esteem during adolescence predict adult depression two decades later. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106(2), 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, D., & Sun, J. (2007). Resilience and depression in children: Mental health promotion in primary schools in China. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 9(4), 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, T. L., & Montgomery, P. (2007). Can cognitive-behavioral therapy increase self-esteem among depressed adolescents? A systematic review. Children and Youth Services Review, 29(7), 823–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzesniewski, K. H., Donnellan, M. B., Moffitt, T. E., Robins, R. W., Poulton, R., & Caspi, A. (2006). Low self-esteem during adolescence predicts poor health, criminal behavior, and limited economic prospects during adulthood. Developmental Psychology, 42(2), 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2002). Self-esteem and socioeconomic status: A meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 6(1), 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. (2020). A series of resources for the MoE-UNICEF social and emotional learning project. Available online: https://www.unicef.cn/documents/sel-resources (accessed on 16 January 2021).

- Veríssimo, L., Castro, I., Costa, M., Dias, P., & Miranda, F. (2022). Socioemotional skills program with a group of socioeconomically disadvantaged young adolescents: Impacts on self-concept and emotional and behavioral problems. Children, 9(5), 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C., Hatzigianni, M., Shahaeian, A., Murray, E., & Harrison, L. J. (2016). The combined effects of teacher-child and peer relationships on children’s social-emotional adjustment. Journal of School Psychology, 59, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissberg, R. P., Durlak, J. A., Domitrovich, C. E., & Gullotta, T. P. (2015). Social and emotional learning: Past, present, and future. In R. P. Weissberg, J. A. Durlak, C. E. Domitrovich, & T. P. Gullotta (Eds.), Handbook of social and emotional learning: Research and practice (pp. 3–19). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, J. E., & Kao, C.-P. (2019). Aspects of socio-emotional learning in Taiwan’s pre-schools: An exploratory study of teachers’ perspectives. International Journal of Child Care and Education Policy, 13(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y., Li, S., & Chen, Y. (2025). Measuring child poverty in rural China: Evidence from households with left-behind and non-left-behind children. China Economic Review, 90, 102354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., Zheng, Z., Pan, C., & Zhou, L. (2021). Self-esteem and academic engagement among adolescents: A moderated mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 690828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total (555) | Control (325) | Intervention (230) | χ2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 1.15 | 0.28 | |||

| Male | 272 (49) | 166 (51.1) | 106 (46.1) | ||

| Female | 283 (51) | 159 (48.9) | 124 (53.9) | ||

| Grade | 10.98 | 0.03 | |||

| 2nd | 103 (18.6) | 65 (20) | 38 (16.5) | ||

| 3rd | 116 (20.9) | 64 (19.7) | 52 (22.6) | ||

| 4th | 143 (25.8) | 78 (24) | 65 (28.3) | ||

| 5th | 109 (19.6) | 57 (17.5) | 52 (22.6) | ||

| 6th | 84 (15.1) | 61 (18.8) | 23 (10) | ||

| Live with | 8.63 | 0.01 | |||

| Both parents | 326 (58.7) | 201 (67.9) | 125 (55.8) | ||

| One parent | 117 (21.1) | 60 (20.3) | 57 (25.4) | ||

| Neither parent | 77 (13.9) | 35 (11.8) | 42 (18.8) | ||

| Father migrant worker | 7.49 | 0.02 | |||

| Yes | 318 (57.3) | 182 (56.7) | 136 (59.4) | ||

| No | 151 (27.2) | 100 (31.2) | 51 (22.3) | ||

| Do not know | 81 (14.6) | 39 (12.1) | 42 (18.3) | ||

| Mother migrant worker | 4.83 | 0.09 | |||

| Yes | 180 (32.4) | 104 (32.5) | 76 (33.2) | ||

| No | 308 (55.5) | 188 (58.8) | 120 (52.4) | ||

| Don’t know | 61 (11) | 28 (8.8) | 33 (14.4) | ||

| Family economic status | 0.002 | 0.96 | |||

| Above average | 178 (32.1) | 104 (32) | 74 (32.2) | ||

| Average or below | 284 (51.2) | 164 (50.5) | 120 (52.2) | ||

| Academic performance | 4.82 | 0.09 | |||

| Top 30% | 216 (38.9) | 130 (40.1) | 86 (38.4) | ||

| Middle 50% | 211 (38) | 114 (35.2) | 97 (43.3) | ||

| Bottom 20% | 121 (21.8) | 80 (24.7) | 41 (18.3) | ||

| Treatment Group | ||||||||

| Control | Intervention | |||||||

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | t | d | p | ||

| Self-esteem | Assessment 1 | 320 | 12.28 (2.61) | 229 | 12.14 (2.8) | 0.58 | 0.05 | 0.56 |

| Assessment 2 | 313 | 12.63 (2.73) | 224 | 12.96 (2.86) | −1.31 | −0.11 | 0.19 | |

| Assessment 3 | 325 | 12.4 (2.93) | 230 | 12 (2.84) | 1.58 | 0.14 | 0.11 | |

| Self-efficacy | Assessment 1 | 322 | 8.9 (2.27) | 225 | 9.1 (2.34) | −0.75 | −0.07 | 0.46 |

| Assessment 2 | 324 | 9.28 (2.18) | 229 | 9.11 (2.19) | 0.87 | 0.08 | 0.39 | |

| Assessment 3 | 325 | 8.9 (2.35) | 230 | 8.82 (2.15) | 0.65 | 0.06 | 0.52 | |

| Family Economic Status | ||||||||

| Above Average | Average or Below | |||||||

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | t | d | p | ||

| Self-esteem | Assessment 1 | 177 | 13.08 (2.53) | 281 | 12.04 (2.55) | 4.28 | 0.41 | <0.001 |

| Assessment 2 | 174 | 13.36 (2.6) | 274 | 12.59 (2.82) | 2.95 | 0.29 | 0.003 | |

| Assessment 3 | 178 | 12.87 (2.67) | 284 | 12.06 (2.81) | 3.13 | 0.30 | 0.002 | |

| Self-efficacy | Assessment 1 | 177 | 9.49 (2.27) | 279 | 8.71 (2.28) | 3.54 | 0.34 | <0.001 |

| Assessment 2 | 178 | 9.65 (2.19) | 283 | 9.1 (2.12) | 2.68 | 0.26 | 0.008 | |

| Assessment 3 | 178 | 9.39 (2.07) | 284 | 8.79 (2.21) | 2.96 | 0.28 | 0.003 | |

| Model on Self-Esteem | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effect | |||||

| Coefficient (B) | 95%CI | SE | t | p | |

| Intervention | −0.16 | [−0.63, 0.32] | 0.24 | −0.65 | 0.52 |

| Assessment 2 | 0.24 | [−0.08, 0.57] | 0.17 | 1.45 | 0.15 |

| Assessment 3 | 0.02 | [−0.31, 0.34] | 0.16 | 0.1 | 0.92 |

| Intervention × Assessment 2 | 0.57 | [0.07, 1.07] | 0.25 | 2.24 | 0.025 |

| Intervention × Assessment 3 | −0.18 | [−0.67, 0.31] | 0.25 | −0.72 | 0.47 |

| Random effect | |||||

| Variance | S.D. | ||||

| Participant (Intercept) | 3.39 | 1.84 | |||

| Residual | 4.1 | 2.03 | |||

| Model fit | |||||

| R2 | Marginal | Conditional | |||

| 0.04 | 0.48 | ||||

| Model on self-efficacy | |||||

| Fixed effect | |||||

| Coefficient (B) | 95%CI | SE | t | p | |

| Intervention | 0.18 | [−0.21, 0.57] | 0.2 | 0.9 | 0.37 |

| Assessment 2 | 0.38 | [0.08, 0.67] | 0.15 | 2.52 | 0.01 |

| Assessment 3 | 0.03 | [−0.26, 0.32] | 0.15 | 0.22 | 0.83 |

| Intervention × Assessment 2 | −0.32 | [−0.77, 0.13] | 0.23 | −1.41 | 0.16 |

| Intervention × Assessment 3 | −0.28 | [−0.73, 0.17] | 0.23 | −1.21 | 0.23 |

| Random effect | |||||

| Variance | S.D. | ||||

| Participant (Intercept) | 1.58 | 1.26 | |||

| Residual | 3.4 | 1.83 | |||

| Model fit | |||||

| R2 | Marginal | Conditional | |||

| 0.02 | 0.33 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, J.; Zhu, L.; Hesketh, T. Improving Confidence and Self-Esteem Among Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Children: A Social Emotional Learning Intervention in Rural China. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1352. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101352

Li J, Zhu L, Hesketh T. Improving Confidence and Self-Esteem Among Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Children: A Social Emotional Learning Intervention in Rural China. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1352. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101352

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Jiameng, Lin Zhu, and Therese Hesketh. 2025. "Improving Confidence and Self-Esteem Among Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Children: A Social Emotional Learning Intervention in Rural China" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 10: 1352. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101352

APA StyleLi, J., Zhu, L., & Hesketh, T. (2025). Improving Confidence and Self-Esteem Among Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Children: A Social Emotional Learning Intervention in Rural China. Behavioral Sciences, 15(10), 1352. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101352