Differences in Experiencing Well-Being in Youth Choir Singers Regarding (In)Formal Participation

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. School-Based (Formal) Participation

1.2. Extracurricular (Informal) Choir Participation

1.3. Formal and Informal Choir Participation

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure

2.2. Participants

2.3. Questionnaire Structure

2.3.1. Instruments

WHO-5 Well-Being Index

Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS)

Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF)

Social Provision Scale (SPS-10)

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS)

Choral Activity Perceived Benefits Scale (CAPBES)

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Validity and Reliability

2.4.2. Factor Refinement

3. Results

3.1. Rehearsal Frequencies

3.2. Well-Being

3.2.1. General Well-Being and Life Satisfaction

3.2.2. Emotional Well-Being

General Life Context

Choir Context

3.3. Social Support

3.4. Mental Health

3.5. Perceived Benefits from Choral Singing

3.6. Factors Within Choir Contributing to Well-Being

3.7. Summary of Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BPNs | Basic psychological needs |

| CAPBES | Choral Activity Perceived Benefits Scale |

| CFA | Confirmatory factor analysis |

| CFI | Comparative fit index |

| EFA | Exploratory factor analysis |

| MHC-SF | Mental Health Continuum Short Form |

| NAS | Negative Affect Schedule |

| PANAS | Positive and Negative Affect Schedule |

| PAS | Positive Affect Schedule |

| RMSEA | Root mean square error of approximation |

| SEM | Structural equation modeling |

| SDT | Self-determination theory |

| SPS | Social Provision Scale |

| SWLS | Satisfaction with Life Scale |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis index |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Acquah, E. O. (2016). Choral singing and well-being: Findings from a survey of the mixed-chorus experience from music students of the University of Education Winneba, Ghana. Legon Journal of the Humanities, 27(2), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J. J. (2013). Adolescence and emerging adulthood: A cultural approach (5th ed.). Pearson Education New Zealand. ISBN 978-1-292-05171-0. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, M., & Vermeulen, D. (2019). Drop everything and sing the music: Choristers’ perceptions of the value of participating in a multicultural South African University Choir. Muziki, 16, 31–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bech, P. (2004). Measuring the dimension of psychological general well-being by the WHO-5. Quality of Life Newsletter, 32, 15–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen, & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Caron, J. (2013). A validation of the social provisions scale: The SPS-10 items. Santé Mentale au Québec, 38(1), 297–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clift, S., Hancox, G., Morrison, I., Hess, B., Kreutz, G., & Stewart, D. (2010). Choral singing and psychological well-being: Quantitative and qualitative findings from English choirs in a cross-national survey. Journal of Applied Arts and Health, 1(1), 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutrona, C. E., & Russell, D. W. (1987). Social provisions scale [Database record]. APA PsycTests. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damsgaard, J. B., & Brinkmann, S. (2022). Me and us: Cultivating presence and mental health through choir singing. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 36(4), 1134–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiksund, Ø. J. (2022). Rethinking motivation in choir participation: Proposing a contextual model of motivation. In R. V. Strøm, Ø. J. Eiksund, & A. H. Balsnes (Eds.), Samsang gjennom livsløpet (pp. 229–255). Cappelen Damm Akademisk. [Google Scholar]

- Fancourt, D., Finn, S., Warran, K., & Wiseman, T. (2022). Group singing in bereavement: Effects on mental health, self-efficacy, self-esteem and well-being. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care, 12(4), 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fancourt, D., Warran, K., Finn, S., & Wiseman, T. (2019). Psychosocial singing interventions for the mental health and well-being of family carers of patients with cancer: Results from a longitudinal controlled study. BMJ Open, 9(8), e026995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Herranz, N., Ferreras-Mencia, S., Arribas-Marín, J. M., & Corraliza, J. A. (2021). Choral singing and personal well-being: A choral activity perceived benefits scale (CAPBES). Psychology of Music, 50(3), 895–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glew, S. G., Simonds, L. M., & Williams, E. I. (2020). The effects of group singing on the well-being and psychosocial outcomes of children and young people: A systematic integrative review. Arts & Health, 13(3), 240–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, A., & Russo, F. A. (2021). Changes in mood, oxytocin and cortisol following group and individual singing: A pilot study. Psychology of Music, 50(4), 1340–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, G. (2018). A qualitative study on the contribution of the choir to social-cultural and psychological achievements of amateur chorists. International Education Studies, 11(8), 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hylton, J. B. (1981). Dimensionality in High School Student Participants’ Perceptions of the Meaning of Choral Singing Experience. Journal of Research in Music Education, 29(4), 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jozić, M., & Butković, A. (2023). Singing and well-being indicators. Psychological Topics, 32(1), 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan-Morera, B., NadalGarcía, I., López-Casanova, B., & Estella-Escobar, L. (2024). Exploratory study on the impact on emotional health derived from participation in an inclusive choir. Healthcare, 12, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyes, C. L. M. (2009). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. In B. F. Gentile, & B. O. Miller (Eds.), Foundations of psychological thought: A history of psychology (pp. 601–617). Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Koulouriotou, E., & Papakitsos, E. (2023). Studying the effects of choir participation on pupils of a greek secondary school. Global Academic Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 5(6), 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamers, S. M., Westerhof, G. J., Bohlmeijer, E. T., ten Klooster, P. M., & Keyes, C. L. (2011). Evaluating the psychometric properties of the mental health continuum-short form (MHC-SF). Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(1), 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S., O’Neill, D., & Moss, H. (2022). Promoting well-being among people with early-stage dementia and their family carers through community-based group singing: A phenomenological study. Arts & Health, 14(1), 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnemann, A., Schnersch, A., & Nater, U. M. (2017). Testing the beneficial effects of singing in a choir on mood and stress in a longitudinal study: The role of social contacts. Musicae Scientiae, 21(2), 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livesey, L., Morrison, I., Clift, S., & Camic, P. (2012). Benefits of choral singing for social and mental well-being: Qualitative findings from a cross-national survey of choir members. Journal of Public Mental Health, 11(1), 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonsdale, A. J., & Day, E. R. (2020). Are the psychological benefits of choral singing unique to choirs? A comparison of six activity groups. Psychology of Music, 49(5), 1179–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, H., Lynch, J., & O’Donoghue, J. (2018). Exploring the perceived health benefits of singing in a choir: An international cross-sectional mixed-methods study. Perspectives in Public Health, 138(3), 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orpana, H., Vachon, J., Dykxhoorn, J., & Jayaraman, G. (2017). Measuring positive mental health in Canada: Construct validation of the mental health continuum-short form. Mesurer la santé mentale positive au Canada: Validation des concepts du Continuum de santé mentale—Questionnaire abrégé. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada: Research, Policy and Practice, 37(4), 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, E. C. (2014). The process of social identity development in adolescent high school choral singers: A grounded theory. Journal of Research in Music Education, 62(1), 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, M. (2023, May 21–22). The importance of choral singing for children’s mental well-being. 25th Pedagogical Forum of Performing Arts: Music and Meaning (pp. 89–101), Belgrade, Serbia. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sischka, P. E., Albert, I., & Kornadt, A. E. (2024). Validation of the 10-item social provision scale (SPS-10): Evaluating factor structure, reliability, measurement invariance, and nomological network across 38 countries. Assessment, 32(7), 1027–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanović, D., & Milošević, I. (2019). (Lack) of pupils’ motivation for choral singing in elementary schools in Niš. Teaching, Learning and Teacher Education, 3(2), 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Jamovi Project. (2022). Jamovi. (Version 2.3) [Computer Software]. Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Topp, C. W., Østergaard, S. D., Søndergaard, S., & Bech, P. (2015). The WHO-5 well-being index: A systematic review of the literature. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 84(3), 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viola, E., Martorana, M., Airoldi, C., Caristia, S., Ceriotti, D., De Vito, M., Tucci, R., Meini, C., Guiot, G., & Faggiano, F. (2024). Dedalo vola project: The effect of choral singing on physiological and psychosocial measures. An Italian pilot study. Acta Psychologica, 244, 104204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. (2024). Mental health of children and young people service guidance. WHO. ISBN 978-92-4-010037-4. [Google Scholar]

| Choir Settings | Study and Year | Sample | Well-Being Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formal | Acquah (2016) | University (emerging adults) |

|

| Stojanović and Milošević (2019) | School (adolescents) | ||

| Koulouriotou and Papakitsos (2023) | |||

| Informal | Barrett and Vermeulen (2019) | University (emerging adults) |

|

| Linnemann et al. (2017) | |||

| Petrović (2023) | Extracurricular (adolescents) | ||

| Formal and informal | Glew et al. (2020) | School/extracurricular (adolescents) |

|

| Parker (2014) |

| Characteristics | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 50 | 18.2% |

| Female | 223 | 81.4% |

| Other | 1 | 0.4% |

| Age group | ||

| 15–19 | 198 | 72.3% |

| 20–24 | 76 | 27.7% |

| Country | ||

| Serbia | 95 | 34.7% |

| Slovenia | 179 | 65.3% |

| Choir settings | ||

| School | 197 | 71.9% |

| Extracurricular | 77 | 28.1% |

| Choir type | ||

| Mixed | 147 | 53.6% |

| Female | 108 | 39.4% |

| Male | 19 | 6.9% |

| Youth Age Group | Choir Type | N | % of Total | % Within the Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescents (15–19) | School | 157 | 57.3% | 79.7% |

| Extracurricular | 41 | 15% | 20.8% | |

| Emerging adults (20–24) | School | 40 | 14.6% | 52.6% |

| Extracurricular | 36 | 13.1% | 46.8% |

| Scale | Cronbach’s α | CFI | TLI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WHO-5 (whole scale) | 0.816 | 0.942 | 0.885 | 0.144 |

| SWLS (whole scale) | 0.798 | 0.954 | 0.908 | 0.125 |

| PAS in life (factor refinement) | 0.678 | 0.839 | 0.773 | 0.088 |

| NAS in life (factor refinement) | 0.782 | 0.772 | 0.680 | 0.132 |

| PAS in choir (factor refinement) | 0.876 | 0.959 | 0.946 | 0.069 |

| NAS in choir (one item excluded) | 0.847 | 0.910 | 0.842 | 0.122 |

| CAPBES (factor refinement) | 0.926 | 0.922 | 0.909 | 0.072 |

| MHC-SF (factor refinement) | 0.908 | 0.865 | 0.841 | 0.106 |

| SPS-10 (factor refinement) | 0.901 | 0.932 | 0.907 | 0.101 |

| Rehearsals per Week | Choir Settings | n | % Within Group | Total % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | School | 197 | 46 (23.3%) | 101 (37.1%) |

| Extracurricular | 77 | 55 (71.4%) | ||

| 1–2 | School | 197 | 5 (2.6%) | 8 (2.9%) |

| Extracurricular | 77 | 3 (3.9%) | ||

| 2 | School | 197 | 109 (55.3%) | 122 (44.9%) |

| Extracurricular | 77 | 13 (16.9%) | ||

| 2–3 | School | 197 | 6 (3%) | 8 (2.9%) |

| Extracurricular | 77 | 2 (2.6%) | ||

| 3 | School | 197 | 27 (13.7%) | 29 (10.7%) |

| Extracurricular | 77 | 2 (2.6%) | ||

| 3–4 | School | 197 | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.4%) |

| Extracurricular | 77 | 1 (1.3%) | ||

| 4 | School | 197 | 3 (1.5%) | 3 (1.1%) |

| Extracurricular | 77 | 0 (0.0%) |

| Instruments | Factors | Group | N | M | SD | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWLS | One factor | School | 197 | 4.55 | 1.094 | 0.0780 |

| Extracurricular | 77 | 4.49 | 0.969 | 0.1105 | ||

| WHO-5 | One factor | School | 197 | 2.69 | 0.886 | 0.0631 |

| Extracurricular | 77 | 2.90 | 0.847 | 0.0965 | ||

| PAS in life | Energy | School | 197 | 3.17 | 0.797 | 0.0568 |

| Extracurricular | 77 | 3.16 | 0.859 | 0.0979 | ||

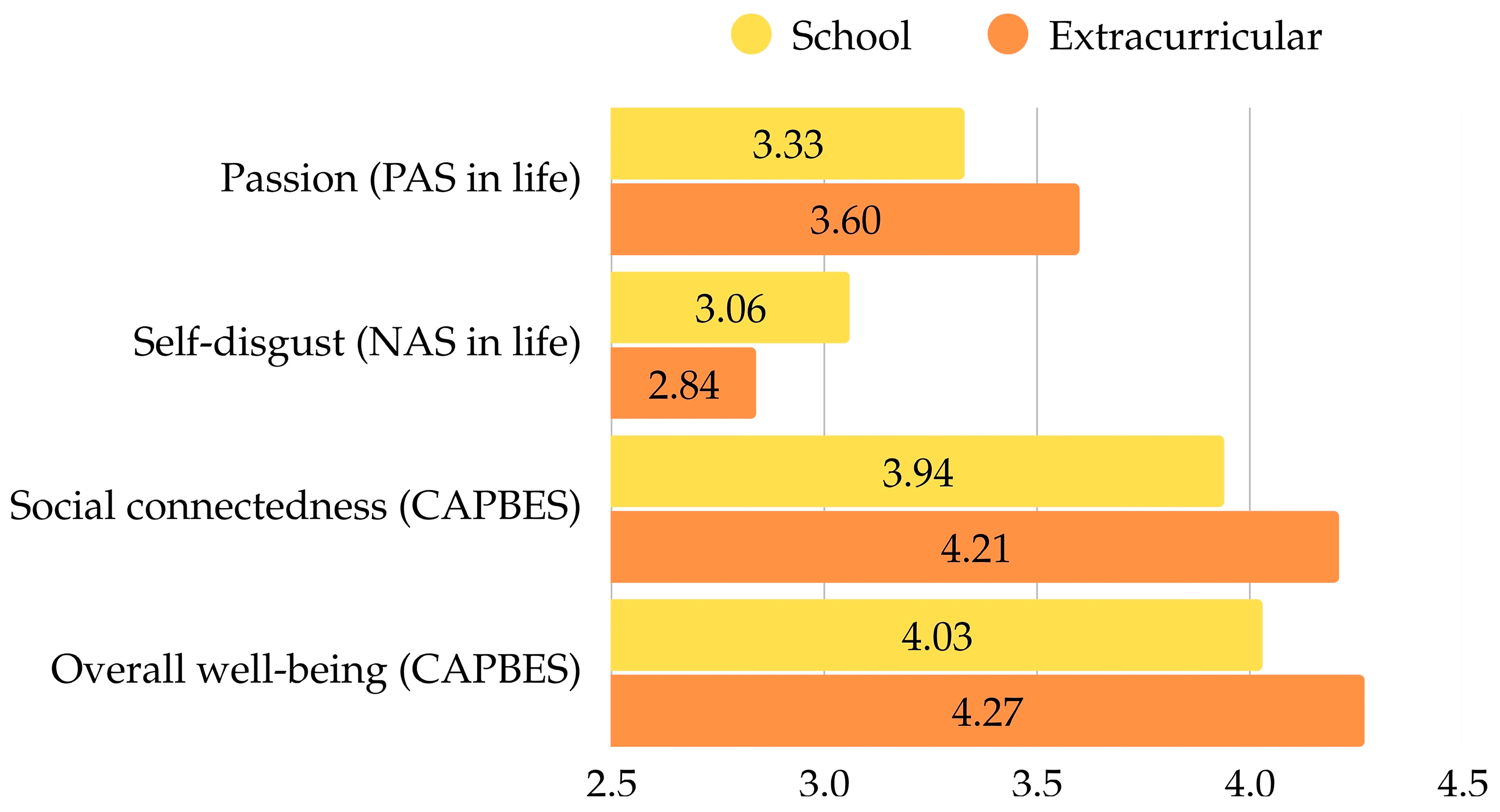

| Passion | School | 197 | 3.33 | 0.888 | 0.0633 | |

| Extracurricular | 77 | 3.60 | 0.855 | 0.0974 | ||

| Engagement | School | 197 | 3.61 | 0.574 | 0.0409 | |

| Extracurricular | 77 | 3.63 | 0.649 | 0.0740 | ||

| NAS in life | Hostility | School | 197 | 2.50 | 0.820 | 0.0584 |

| Extracurricular | 77 | 2.34 | 0.845 | 0.0963 | ||

| Self-disgust | School | 197 | 3.06 | 0.727 | 0.0518 | |

| Extracurricular | 77 | 2.84 | 0.702 | 0.0800 | ||

| Fear | School | 197 | 3.14 | 0.819 | 0.0583 | |

| Extracurricular | 77 | 2.98 | 0.722 | 0.0823 | ||

| PAS in choir | Excitement | School | 197 | 3.76 | 0.784 | 0.0558 |

| Extracurricular | 77 | 3.88 | 0.729 | 0.0831 | ||

| Motivation | School | 197 | 3.89 | 0.766 | 0.0546 | |

| Extracurricular | 77 | 3.98 | 0.627 | 0.0714 | ||

| NAS in choir | Agitation | School | 197 | 1.57 | 0.577 | 0.0411 |

| Extracurricular | 77 | 1.48 | 0.515 | 0.0586 | ||

| Tension | School | 197 | 1.94 | 0.741 | 0.0528 | |

| Extracurricular | 77 | 1.77 | 0.649 | 0.0740 | ||

| CAPBES | Ability | School | 197 | 4.18 | 0.804 | 0.0573 |

| Extracurricular | 77 | 4.25 | 0.729 | 0.0831 | ||

| Optimism | School | 197 | 3.27 | 0.941 | 0.0670 | |

| Extracurricular | 77 | 3.40 | 0.946 | 0.1078 | ||

| Social connectedness | School | 197 | 3.94 | 0.885 | 0.0631 | |

| Extracurricular | 77 | 4.21 | 0.728 | 0.0830 | ||

| Overall wellbeing | School | 197 | 4.03 | 0.912 | 0.0650 | |

| Extracurricular | 77 | 4.27 | 0.657 | 0.0748 | ||

| Accomplishment | School | 197 | 4.43 | 0.739 | 0.0526 | |

| Extracurricular | 77 | 4.50 | 0.641 | 0.0730 | ||

| MHC-SF | One factor | School | 197 | 2.98 | 0.887 | 0.0632 |

| Extracurricular | 77 | 2.93 | 0.934 | 0.1065 | ||

| SPS-10 | Social support | School | 197 | 3.58 | 0.517 | 0.0368 |

| Extracurricular | 77 | 3.61 | 0.458 | 0.0522 | ||

| Social connections | School | 197 | 3.48 | 0.468 | 0.0334 | |

| Extracurricular | 77 | 3.51 | 0.446 | 0.0508 |

| Instruments | Factors | t | Df | p | M Difference | SE Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWLS | One factor | 0.488 | 156 | 0.626 | 0.0660 | 0.1352 |

| WHO-5 | One factor | −1.815 | 145 | 0.072 | −0.2094 | 0.1153 |

| PAS in life | Energy | 0.148 | 130 | 0.883 | 0.0167 | 0.1132 |

| Passion | −2.310 * | 144 | 0.022 | −0.2684 | 0.1162 | |

| Engagement | −0.231 | 125 | 0.817 | −0.0196 | 0.0846 | |

| NAS in life | Hostility | 1.464 | 135 | 0.145 | 0.1649 | 0.1126 |

| Self-disgust | 2.292 * | 143 | 0.023 | 0.2184 | 0.0953 | |

| Fear | 1.635 | 156 | 0.104 | 0.1649 | 0.1009 | |

| PAS in choir | Excitement | −1.174 | 148 | 0.242 | −0.1175 | 0.1001 |

| Motivation | −1.051 | 168 | 0.295 | −0.0945 | 0.0899 | |

| NAS in choir | Agitation | 1.239 | 155 | 0.217 | 0.0888 | 0.0716 |

| Tension | 1.772 | 157 | 0.078 | 0.1610 | 0.0909 | |

| CAPBES | Ability | −0.711 | 152 | 0.478 | −0.0718 | 0.1010 |

| Optimism | −0.991 | 138 | 0.323 | −0.1258 | 0.1269 | |

| Social connectedness | −2.579 * | 167 | 0.011 | −0.2687 | 0.1042 | |

| Overall well-being | −2.419 * | 192 | 0.016 | −0.2397 | 0.0991 | |

| Accomplishment | −0.840 | 159 | 0.402 | −0.0756 | 0.0900 | |

| MHC-SF | One factor | 0.442 | 133 | 0.659 | 0.0548 | 0.1238 |

| SPS-10 | Social support | −0.516 | 156 | 0.606 | −0.0330 | 0.0639 |

| Social connections | −0.526 | 145 | 0.599 | −0.0320 | 0.0608 |

| Factors | Choir Settings | M | SD | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 Socializing with other choir members | School | 3.87 | 0.938 | −2.732 * | 0.007 |

| Extracurricular | 4.17 | 0.768 | |||

| F2 Achieving personal singing potential | School | 3.85 | 0.939 | −0.141 | 0.888 |

| Extracurricular | 3.87 | 0.908 | |||

| F3 Participating in contests | School | 3.25 | 1.16 | 1.400 | 0.164 |

| Extracurricular | 3.01 | 1.32 | |||

| F4 Performing concerts | School | 3.96 | 0.992 | 0.754 | 0.452 |

| Extracurricular | 3.86 | 1.08 | |||

| F5 Choir repertoire | School | 3.64 | 1.01 | −2.238 * | 0.027 |

| Extracurricular | 3.91 | 0.846 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Blagojević, J.; Habe, K.; Bajec, B. Differences in Experiencing Well-Being in Youth Choir Singers Regarding (In)Formal Participation. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1337. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101337

Blagojević J, Habe K, Bajec B. Differences in Experiencing Well-Being in Youth Choir Singers Regarding (In)Formal Participation. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1337. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101337

Chicago/Turabian StyleBlagojević, Jovana, Katarina Habe, and Boštjan Bajec. 2025. "Differences in Experiencing Well-Being in Youth Choir Singers Regarding (In)Formal Participation" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 10: 1337. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101337

APA StyleBlagojević, J., Habe, K., & Bajec, B. (2025). Differences in Experiencing Well-Being in Youth Choir Singers Regarding (In)Formal Participation. Behavioral Sciences, 15(10), 1337. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101337