White-Collar Workers in the Post-Pandemic Era: A Review of Risk and Protective Factors for Mental Well-Being

Abstract

1. Introduction

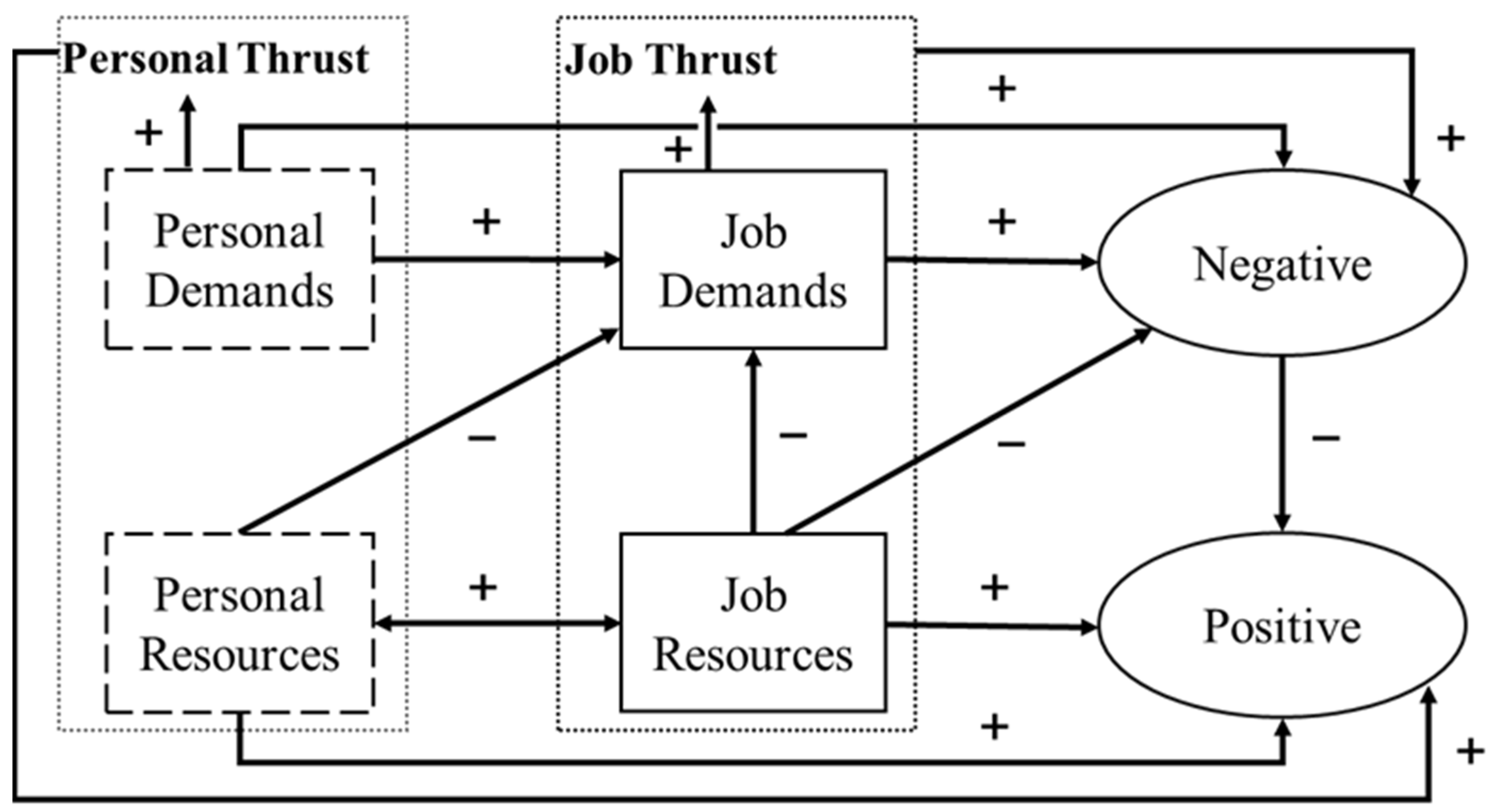

2. Job Demands-Resources Model

3. Changes in the Workplace and Their Impact on White-Collar Workers

3.1. Method

- (1)

- Importance—This review is of great significance to all stakeholders concerned with workplace stress. It may inform relevant interventions, which in turn may help improve workers’ well-being and reduce turnover.

- (2)

- Aims of the review—The primary objective is to synthesize existing evidence on risk factors and protective factors, identifying temporal changes in white-collar workplaces in the context of COVID-19.

- (3)

- Literature search—The Web of Science database was used as the main data source.

- (4)

- (5)

- Evidence—Research design and purpose are included.

- (6)

- Relevant endpoint data—Key findings are included.

3.2. Findings from Pre-COVID-19 Studies

| Author | Design | Purpose | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bhalla et al. (1991) | Cross-sectional study | To examine various stressors at work and outside work. | Among work stressors, conflict, ambiguity, and insufficiency were most closely tied to vocational outcomes. |

| Bilgel et al. (2006) | Cross-sectional study | To determine the prevalence of reported workplace bullying among a group of white-collar workers, to assess its impact on health, and to evaluate the effectiveness of workplace support for bullied employees. | White-collar workers who experienced workplace bullying reported higher levels of anxiety, depression, and overall lower mental well-being. |

| Bourbonnais et al. (1996) | Cross-sectional study | To assess if workers under high job strain, defined as high psychological demands and low decision latitude, experience more psychological distress than those not under high job strain. | Workers facing high job strain, characterized by high demands and low control, suffer more psychological distress than those with lower job strain. |

| Hagihara et al. (1998) | Cross-sectional study | To evaluate the relative importance of work and non-work factors in deciding the subject’s job satisfaction level. | The results suggest improving job satisfaction is more effectively achieved through company policies, such as clear communication, professional development, fair compensation, and a supportive work environment, rather than individual efforts. |

| Hagihara et al. (2000) | Cross-sectional study | To assess after-work drinking interactions with coworkers and work stressor variables among white-collar workers. | The findings suggest that after-work drinking with coworkers alleviated job dissatisfaction, but only for those with lower levels of work stress. |

| Hansen et al. (2010) | Longitudinal study | To investigate the link between physical activity and perceived job demand, job control, stress, energy, and cortisol levels (morning and evening) in saliva among white-collar workers. | Physically active employees perceive less stress and more energy. Vigorous physical activity influenced the relationship between stress, energy, and salivary cortisol. |

| Hino et al. (2019) | Longitudinal study | To examine the impact of changes in overtime hours on depressive symptoms among white-collar workers. | Reducing overtime hours may protect mental health. |

| Kageyama et al. (2001) | Cross-sectional study | To identify the factors influencing sleep debt on weekdays among Japanese white-collar workers. | Sleep debt on weekdays in Japanese white-collar workers was positively associated with age, overtime, and self-rated workload. |

| Lindfors et al. (2006) | Cross-sectional study | To study the relationship between total workload (paid and unpaid) and psychological well-being and symptoms in full-time employed women and men. | Among full-time white-collar workers, gender differences were significant. Increased unpaid work hours decreased self-acceptance and environmental mastery in women, while paid work increased personal growth but decreased life goals. Men reported more personal growth in paid work. |

| Lundberg et al. (1994) | Cross-sectional study | To assess various aspects of paid and unpaid forms of productive activity among white-collar workers. | Women report more stress and work conflict than men, especially those aged 35–39 with children. Men enjoy more workplace autonomy. Higher management experiences less conflict and more control. |

| Moisan et al. (1999) | Cross-sectional study | To assess the link between high psychological demand, low decision latitude at work, and the use of psychotropic drugs among white-collar workers. | Job strain may determine psychotropic drug use among white-collar workers, but workplace social support does not seem to affect this link. |

| Renault Moraes et al. (1993) | Cross-sectional study | To study occupational stress in a medium-sized government organization. | Younger employees and women experienced the highest levels of occupational stress. |

| Morissette and Dedobbeleer (1997) | Cross-sectional study | To hypothesize the contribution of specific professional factors to women’s long-term use of prescribed psychotropic drugs. | Results suggest that a high-stress work environment leads to increased prescribed drug consumption. |

| Nakamura et al. (2011) | Cross-sectional study | To clarify the factors that lead to depression. | There are close relationships between depression in white-collar workers and their characteristics, feelings of self-esteem, and psychological stress experienced outside rather than inside the workplace. |

| Sandmark and Renstig (2010) | Qualitative study | To understand impaired work ability, leading ultimately to long-term sick leave. | Work and private life factors were crucial in the informants’ deteriorating health and long-term sick leave. Job mismatches, company profitability issues, and poor leadership led to stress-related symptoms and decreased work capacity. |

| Tokuyama et al. (2003) | Longitudinal study | To identify risk factors for depression among workers. | Major depression in white-collar workers is associated with job stress, insufficient social support, extended work hours, and poor work–life balance. |

| Tsai (2012) | Cross-sectional study | To explore health-related quality of life and work-related stress and their risk factors. | Perceived work-related stress and depression indirectly influence health-related quality of life by mediating the link between job demands and health outcomes. |

3.3. Findings from Post-COVID-19 Studies

| Author | Design | Purpose | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Al Riyami et al. (2024) | Cross-sectional study | To understand how the emotions of employees are affected by work-from-home measures. | The protective effect of mindfulness on reducing workplace ostracism is stronger with moderate to high organizational support but not when support is low. |

| Barath and Schmidt (2022) | Cross-sectional study | To discuss the changes employers will apply regarding the work environment and office layout. | The findings suggest that an increasingly mobile workforce and expanding new work styles may not necessarily result in an office exodus. Still, they will undoubtedly lead to more flexible and reduced office utilization. |

| Çemberci et al. (2022) | Cross-sectional study | To examine how marital status, job experience, and having children affect work engagement in white-collar workers with flexible hours. | There is a significant positive relationship between job experience and work engagement. Additionally, job satisfaction, organizational support, and work–life balance significantly influence work engagement. |

| Chafi et al. (2022) | Qualitative study | To identify needs, challenges, and sustainability potential in remote and hybrid work. | Individuals gain flexibility but struggle with boundaries. Groups benefit from digital tools but face reduced cohesion. Leaders can innovate but must ensure resource equity. |

| Costin et al. (2023) | Systematic literature review | To analyze evidence on how remote employees without consistent organizational support during COVID-19 faced increased job demands, strain, low satisfaction, and burnout. | Severe psychological symptoms and stress were linked to poor organizational communication and rising workload. |

| Henke et al. (2022) | Qualitative study | To identify factors influencing success in remote work. | Regular mindfulness practice among employees significantly reduces workplace stress and improves overall job satisfaction and productivity. |

| Jamal et al. (2024) | Longitudinal study | To explore the adverse employee outcomes of working from home. | Employees experienced increased job demands during COVID-19. |

| Kohn et al. (2025) | Mixed study | To learn about employees’ digital resilience from enforced remote work transitions. | Digital resilience in employees hinges on organizational support, technical resources, and their ability to utilize communication technologies effectively. |

| Kumar et al. (2023) | Cross-sectional study | To study factors affecting the amount of work done at home. | Longer work-from-home exposure, greater work experience, and support roles increased the likelihood of maintaining or increasing home work. |

| Lathabhavan and Griffiths (2024) | Cross-sectional study | To investigate the role of technology, manager support, and peer support on self-efficacy and job outcomes of employees while working from home. | The study demonstrated the importance of social persuasion (including technology) while working from home in enhancing employees’ self-efficacy and job outcomes. |

| Levacher et al. (2023) | Longitudinal study | To investigate longitudinal changes in mental well-being during the first lockdown of the COVID-19 pandemic. | Personality traits significantly impact mental well-being. Key traits such as extraversion, conscientiousness, and emotional stability were particularly important in determining overall mental health outcomes. |

| Plester and Lloyd (2023) | Qualitative study | To explore how workplace fun and psychological safety impact a positive work environment. | Hybrid work can lead to greater interpersonal ambiguity due to the lack of embodied cues in virtual interactions. This absence of non-verbal communication, such as body language and facial expressions, can result in misunderstandings and reduced team cohesion. |

| Radu et al. (2023) | Cross-sectional study | To understand remote work’s impact on employee perception, psychological safety, and job performance is crucial for organizations. | When psychological safety is high, the positive relationship between employee sentiment around remote work and work performance is stronger. |

| Rodriguez-Lopez and Rubio-Valdehita (2021) | Cross-sectional study | To assess how sociodemographic variables, pandemic concern, and personality predict burnout. | Personality significantly affects workers’ pandemic-related job concerns and burnout development. |

| Uzkurt et al. (2025) | Cross-sectional study | To explore the effect of government support on employees’ job performance and motivation perceptions. | Government support positively impacts employees’ motivation and job performance. |

| Venkatesh et al. (2021) | Quasi-experimental study | To test the moderating effect of situational strength. | COVID-19-induced changes in situational strength may increase burnout, dissatisfaction, and turnover risk among conscientious employees if not managed well. |

| L. Y. Wang and Xie (2023) | Cross-sectional study | To explore how flexible work arrangements impact employee innovation performance. | Flexible work arrangements increase role ambiguity and reduce innovation but also boost psychological empowerment and enhance it. |

| Y. Z. Wang and Yu (2023) | Cross-sectional study | To identify spousal support factors affecting female knowledge workers’ work-from-home outcomes and willingness. | The findings could explain how a husband’s support can improve his wife’s well-being when working from home. |

| R. Wang et al. (2022) | Longitudinal study | To understand the impact of factors on work-from-home behavior. | Remote work significantly enhances job satisfaction and productivity, especially when employees receive adequate organizational support and resources. |

| Author | Design | Purpose | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fan and Moen (2023) | Longitudinal study | To comprehend the structured dynamics of subjective well-being linked with changing workplaces. | Cluster analysis revealed four distinct patterns of well-being based on burnout, work–life conflict, and satisfaction with job and life. |

| Gibson et al. (2023) | Qualitative study | To investigate the effects of returning to office work on employee productivity, mental health, and overall job satisfaction following the COVID-19 pandemic. | Returning to office work improved employee productivity but had mixed effects on mental health and job satisfaction, highlighting the need for flexible work options. |

| Han et al. (2024) | Quantitative study | To determine appropriate candidates for telework and to specify which types of workers are best suited for various levels of telework, establish scientifically sound and reasonable hybrid work ratios and procedures, and assess their suitability. | Regular remote work increases employee autonomy and job satisfaction but can also lead to feelings of isolation and decreased team cohesion. |

| Harkiolakis and Komodromos (2023) | Integrative literature review | To explore the impact of hybrid work models on employee engagement and organizational performance, focusing on identifying best practices for implementation. | Knowledge workers thrive in hybrid environments when given empathy, autonomy, flexibility, social interaction opportunities, and professional advancement by organizations. |

| Krajcik et al. (2023) | Cross-sectional study | To ascertain the preferences of employees from culturally diverse backgrounds regarding their work location and schedule following the conclusion of the pandemic. | The suggested hybrid work model appears to be the most fitting solution according to employees’ preferences. |

| Liang et al. (2023) | Cross-sectional study | To examine the link between employees’ expected company-allowed telecommuting levels and their preferred frequency post-pandemic. | A discrepancy was found between the telecommuting frequency companies are expected to allow and the frequency preferred by employees. |

| Massar et al. (2023) | Longitudinal study | To study the impact of working from home on sleep and activity patterns during the later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic transition to normalcy. | Sleep and physical activity changes during the pandemic persisted into later stages, suggesting long-term effects. Efforts are needed to maximize benefits and reduce drawbacks. |

| Pandita et al. (2024) | Qualitative study | To investigate the aspects of return-to-office stress and how organizations can assist employees in managing it. | Hybrid work models significantly enhance work–life balance and job satisfaction but require robust digital infrastructure and clear communication strategies for optimal effectiveness. |

| Qamar et al. (2023) | Mixed study | To examine how high-performance work systems enhance happiness through the sequential pathways of career aspiration and thriving at work. | The study findings reveal a positive relationship between high-performance work systems and career aspiration. |

| Borrelli et al. (2023) | Cross-sectional study | To study the outcomes of anxiety and depression traits in workers under stress-related work. | High demands negatively impacted mental health, while strong management, support, and positive relationships were associated with improved mental health outcomes. |

| Wallberg et al. (2023) | Qualitative study | To examine the long-term effects of remote work on employee collaboration, innovation, and organizational culture in various industries. | Pandemic-induced changes in working conditions caused difficulties for young employees and managers when flexibility was insufficient. |

4. Occupational Health Psychology in the Post-Pandemic World

4.1. Stress

4.2. Depression

4.3. Burnout

4.4. Thriving

4.5. Work Engagement

4.6. Workaholism

4.7. Motivation

4.8. Workplace Civility

4.9. Resilience

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al Riyami, S., Razzak, M. R., & Al-Busaidi, A. S. (2024). Mindfulness and workplace ostracism in the post-pandemic work from home arrangement: Moderating the effect of perceived organizational support. Evidence-Based HRM, 12(2), 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyagari, R., Grover, V., & Purvis, R. (2011). Technostress: Technological antecedents and implications. Mis Quarterly, 35(4), 831–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baethge, C., Goldbeck-Wood, S., & Mertens, S. (2019). SANRA—A scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Research Integrity and Peer Review, 4(1), 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barath, M., & Schmidt, D. A. (2022). Offices after the COVID-19 pandemic and changes in perception of flexible office space. Sustainability, 14(18), 11158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalla, S., Jones, B., & Flynn, D. M. (1991). Role stress among canadian white-collar workers. Work and Stress, 5(4), 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgel, N., Aytac, S., & Bayram, N. (2006). Bullying in Turkish white-collar workers. Occupational Medicine, 56(4), 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Borrelli, I., Rossi, M. F., Santoro, P. E., Gualano, M. R., Tannorella, B. C., Perrotta, A., & Moscato, U. (2023). Occupational exposure to work-related stress, a proposal of a pilot study to detect psychological distress in collar-workers. Annali Di Igiene Medicina Preventiva E Di Comunita, 35(5), 521–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourbonnais, R., Brisson, C., Moisan, J., & Vezina, M. (1996). Job strain and psychological distress in white-collar workers. Scandinavian Journal of Work Environment & Health, 22(2), 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chafi, M. B., Hultberg, A., & Yams, N. B. (2022). Post-pandemic office work: Perceived challenges and opportunities for a sustainable work environment. Sustainability, 14(1), 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M. A., Michel, J. S., Zhdanova, L., Pui, S. Y., & Baltes, B. B. (2016). All work and no play? A meta-analytic examination of the correlates and outcomes of workaholism. Journal of Management, 42(7), 1836–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costin, A., Roman, A. F., & Balica, R. S. (2023). Remote work burnout, professional job stress, and employee emotional exhaustion during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1193854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çemberci, M., Civelek, M. E., Ertemel, A. V., & Cömert, P. N. (2022). The relationship of work engagement with job experience, marital status and having children among flexible workers after the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE, 17(11), e0276784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The Job Demands-Resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A., & Gori, A. (2016). Assessing workplace relational civility (WRC) with a new multidimensional “mirror” measure. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W., & Moen, P. (2023). Ongoing remote work, returning to working at work, or in between during COVID-19: What promotes subjective well-being? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 64(1), 152–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, C. B., Gilson, L. L., Griffith, T. L., & O’Neill, T. A. (2023). Should employees be required to return to the office? Organizational Dynamics, 52(2), 100981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagihara, A., Tarumi, K., Babazono, A., Nobutomo, K., & Morimoto, K. (1998). Work versus non-work predictors of job satisfaction among Japanese white-collar workers. Journal of Occupational Health, 40(4), 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagihara, A., Tarumi, K., & Nobutomo, K. (2000). Work stressors, drinking with colleagues after work, and job satisfaction among white-collar workers in Japan. Substance Use & Misuse, 35(5), 737–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Z., Zhao, Y. H., & Chen, M. J. (2024). Research on the suitability of telework in the context of COVID-19. International Journal of Manpower, 45(4), 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, Å. M., Blangsted, A. K., Hansen, E. A., Søgaard, K., & Sjøgaard, G. (2010). Physical activity, job demand–control, perceived stress–energy, and salivary cortisol in white-collar workers. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 83(2), 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harkiolakis, T., & Komodromos, M. (2023). Supporting knowledge workers’ health and well-being in the post-lockdown era. Administrative Sciences, 13(2), 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henke, J. B., Jones, S. K., & O’Neill, T. A. (2022). Skills and abilities to thrive in remote work: What have we learned. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 893895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hino, A., Inoue, A., Mafune, K., & Hiro, H. (2019). The effect of changes in overtime work hours on depressive symptoms among Japanese white-collar workers: A 2-year follow-up study. Journal of Occupational Health, 61(4), 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, M. T., Anwar, I., Khan, N. A., & Ahmad, G. (2024). How do teleworkers escape burnout? A moderated-mediation model of the job demands and turnover intention. International Journal of Manpower, 45(1), 169–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T. A., & Ilies, R. (2002). Relationship of personality to performance motivation: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 797–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kageyama, T., Nishikido, N., Kobayashi, T., & Kawagoe, H. (2001). Estimated sleep debt and work stress in Japanese white-collar workers. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 55(3), 217–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T. (2014). Insomnia symptoms, depressive symptoms, and suicide ideation in Japanese white-collar employees. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 21(3), 506–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleine, A. K., Rudolph, C. W., & Zacher, H. (2019). Thriving at work: A meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(9–10), 973–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, V., Frank, M., & Holten, R. (2025). Lessons on employees’ digital resilience from COVID-19-induced transitions to remote work—A mixed methods study. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 38(1), 176–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajcik, M., Schmidt, D. A., & Barath, M. (2023). Hybrid work model: An approach to work-life flexibility in a changing environment. Administrative Sciences, 13(6), 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N., Alok, S., & Banerjee, S. (2023). Personal attributes and job resources as determinants of amount of work done under work-from-home: Empirical study of Indian white-collar employees. International Journal of Manpower, 44(1), 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laflamme, N., Brisson, C., Moisan, J., Milot, A., Masse, B., & Vezina, M. (1998). Job strain and ambulatory blood pressure among female white-collar workers. Scandinavian Journal of Work Environment & Health, 24(5), 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lathabhavan, R., & Griffiths, M. D. (2024). Antecedents and job outcomes from a self-efficacy perspective while working from home among professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Manpower, 45(2), 217–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levacher, J., Spinath, F. M., Becker, N., & Hahn, E. (2023). How did the beginnings of the global COVID-19 pandemic affect mental well-being? PLoS ONE, 18(1), e0279753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, J., Miwa, T., & Morikawa, T. (2023). Preferences and expectations of Japanese employees toward telecommuting frequency in the post-pandemic era. Sustainability, 15(16), 12611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindfors, P., Berntsson, L., & Lundberg, U. (2006). Total workload as related to psychological well-being and symptoms in full-time employed female and male white-collar workers. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 13(2), 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundberg, U., Mardberg, B., & Frankenhaeuser, M. (1994). The total workload of male and female white-collar workers as related to age, occupational level, and number of children. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 35(4), 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marathe, G. M., Balasubramanian, G., & Chalil, G. (2019). Conceptualising the psychological work states—Extending the JD-R model. Management Research News, 42(10), 1187–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massar, S. A. A., Ong, J. L., Lau, T., Ng, B. L., Chan, L. F., Koek, D., Cheong, K. R., & Chee, M. W. L. (2023). Working-from-home persistently influences sleep and physical activity 2 years after the COVID-19 pandemic onset: A longitudinal sleep tracker and electronic diary-based study. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1145893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, L. H. W., O’Driscoll, M. P., Marsh, N. V., & Brady, E. C. (2001). Understanding workaholism: Data synthesis, theoretical critique, and future design strategies. International Journal of Stress Management, 8(2), 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisan, J., Bourbonnais, R., Brisson, C., Gaudet, M., Vézina, M., Vinet, A., & Grégoire, J. P. (1999). Job strain and psychotropic drug use among white-collar workers. Work and Stress, 13(4), 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morissette, P., & Dedobbeleer, N. (1997). Is work a risk factor in the prescribed psychotropic drug consumption of female white-collar workers and professionals? Women & Health, 25(4), 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K., Seto, H., Okino, S., Ono, K., Ogasawara, M., Shibamoto, Y., Agata, T., & Nakayama, K. (2011). Psychological stress factors related to depression in white-collar workers: Within or outside the workplace. International Medical Journal, 18(2), 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, A., Eva, N., Bindl, U. K., & Stoverink, A. C. (2022). Organizational and vocational behavior in times of crisis: A review of empirical work undertaken during the COVID-19 pandemic and introduction to the special issue. Applied Psychology-An International Review-Psychologie Appliquee-Revue Internationale, 71(3), 743–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okros, N., & Virga, D. (2023). Impact of workplace safety on well-being: The mediating role of thriving at work. Personnel Review, 52(7), 1861–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxford University Press. (n.d.). White-collar, n. & adj. In Oxford English dictionary. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandita, D., Gupta, D., & Vapiwala, F. (2024). Rewinding back into the old normal: Why is return-to-office stressing employees out? Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pflügner, K., Maier, C., & Weitzel, T. (2021). The direct and indirect influence of mindfulness on techno-stressors and job burnout: A quantitative study of white-collar workers. Computers in Human Behavior, 115, 106566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plester, B. A., & Lloyd, R. (2023). Happiness is “being yourself”: Psychological safety and fun in hybrid work. Administrative Sciences, 13(10), 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamar, F., Soomro, S. A., & Kundi, Y. M. (2023). Linking high-performance work systems and happiness at work: Role of career aspiration and thriving. Career Development International, 28(5), 536–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radu, C., Deaconu, A., Kis, I. A., Jansen, A., & Misu, S. I. (2023). New ways to perform: Employees’ perspective on remote work and psychological security in the post-pandemic era. Sustainability, 15(7), 5952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renault Moraes, L. F. D., Swan, J. A., & Cooper, C. L. (1993). A study of occupational stress among government white-collar workers in Brazil using the occupational stress indicator. Stress Medicine, 9(2), 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Lopez, A. M., & Rubio-Valdehita, S. (2021). COVID-19 concerns and personality of commerce workers: Its influence on burnout. Sustainability, 13(22), 12908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandmark, H., & Renstig, M. (2010). Understanding long-term sick leave in female white-collar workers with burnout and stress-related diagnoses: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health, 10(1), 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B. (2017). Applying the Job Demands-Resources model: A ‘how to’ guide to measuring and tackling work engagement and burnout. Organizational Dynamics, 46(2), 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Taris, T. W. (2014). A critical review of the Job Demands-Resources model: Implications for improving work and health. In G. F. Bauer, & O. Hämmig (Eds.), Bridging occupational, organizational and public health: A transdisciplinary approach (pp. 43–68). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokuyama, M., Nakao, K., Seto, M., Watanabe, A., & Takeda, M. (2003). Predictors of first-onset major depressive episodes among white-collar workers. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 57(5), 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S. Y. (2012). A study of the health-related quality of life and work-related stress of white-collar migrant workers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 9(10), 3740–3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzkurt, C., Ceyhan, S., Ekmekcioglu, E. B., & Akpinar, M. T. (2025). Government support, employee motivation and job performance in the COVID-19 times: Evidence from Turkish SMEs during the short work period. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 20(2), 537–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., Ganster, D. C., Schuetz, S. W., & Sykes, T. A. (2021). Risks and rewards of conscientiousness during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(5), 643–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallberg, M., Ljungberg, H. T., Brämberg, E. B., Nybergh, L., Jensen, I., & Olsson, C. (2023). Hindering and enabling factors for young employees with common mental disorder to remain at or return to work affected by the COVID-19 pandemic—A qualitative interview study with young employees and managers. PLoS ONE, 18(6), e0286819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L. Y., & Xie, T. Y. (2023). Double-edged sword effect of flexible work arrangements on employee innovation performance: From the demands-resources-individual effects perspective. Sustainability, 15(13), 10159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R., Ye, Z. N., Lu, M. J., & Hsu, S. C. (2022). Understanding post-pandemic work-from-home behaviours and community level energy reduction via agent-based modelling. Applied Energy, 322, 119433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Z., & Yu, R. F. (2023). The influence of spousal support on the outcomes and willingness of work from home for female knowledge workers. Ergonomics, 67(7), 941–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willeke, K., Janson, P., Zink, K., Stupp, C., Kittel-Schneider, S., Berghoefer, A., Ewert, T., King, R., Heuschmann, P. U., Zapf, A., Wildner, M., & Keil, T. (2021). Occurrence of mental illness and mental health risks among the self-employed: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stress | Psychological responses to workplace demands beyond coping capacity |

| Depression | Negative effects of work stress, persistent moodiness |

| Burnout | Chronic syndrome from prolonged stress: exhaustion + distancing + reduced efficacy |

| Thriving | Maintaining a positive combination of learning and energy despite the pressures of the situation |

| Work Engagement | Positive work state with vigor, dedication, and absorption |

| Workaholism | Compulsive work addiction |

| Motivation | Internal drive directing work behavior |

| Workplace Civility | A work environment characterized by respect and courtesy |

| Resilience | Ability to adapt to and recover from adversity |

| Constructs | Shifts From Pre- to Post-COVID | JD-R Model Alignment |

|---|---|---|

| Stress | Physical → Digital stressors |

|

| Depression | Traditional → Instable mode |

|

| Burnout | Contextual shift from office → virtual exhaustion |

|

| Thriving | Formal → informal development pathways |

|

| Work Engagement | Fixed → flexible workplace/time |

|

| Workaholism | Observable → invisible overwork |

|

| Motivation | Organizational → personal value |

|

| Workplace Civility | Embodied → mediated interactions |

|

| Resilience | Static trait → dynamic skill set |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Meng, J.; Suárez, L.; Yip, C.C.E.; Marsh, N.V. White-Collar Workers in the Post-Pandemic Era: A Review of Risk and Protective Factors for Mental Well-Being. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1313. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101313

Meng J, Suárez L, Yip CCE, Marsh NV. White-Collar Workers in the Post-Pandemic Era: A Review of Risk and Protective Factors for Mental Well-Being. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1313. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101313

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeng, Junyi, Lidia Suárez, Chad C. E. Yip, and Nigel V. Marsh. 2025. "White-Collar Workers in the Post-Pandemic Era: A Review of Risk and Protective Factors for Mental Well-Being" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 10: 1313. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101313

APA StyleMeng, J., Suárez, L., Yip, C. C. E., & Marsh, N. V. (2025). White-Collar Workers in the Post-Pandemic Era: A Review of Risk and Protective Factors for Mental Well-Being. Behavioral Sciences, 15(10), 1313. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101313