The Impact of Agreeableness Trait on Volunteer Service Motivation and Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Study of Chinese College Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Agreeableness Traits and Volunteer Service Behavior

2.2. The Mediating Role of Volunteer Service Motivation

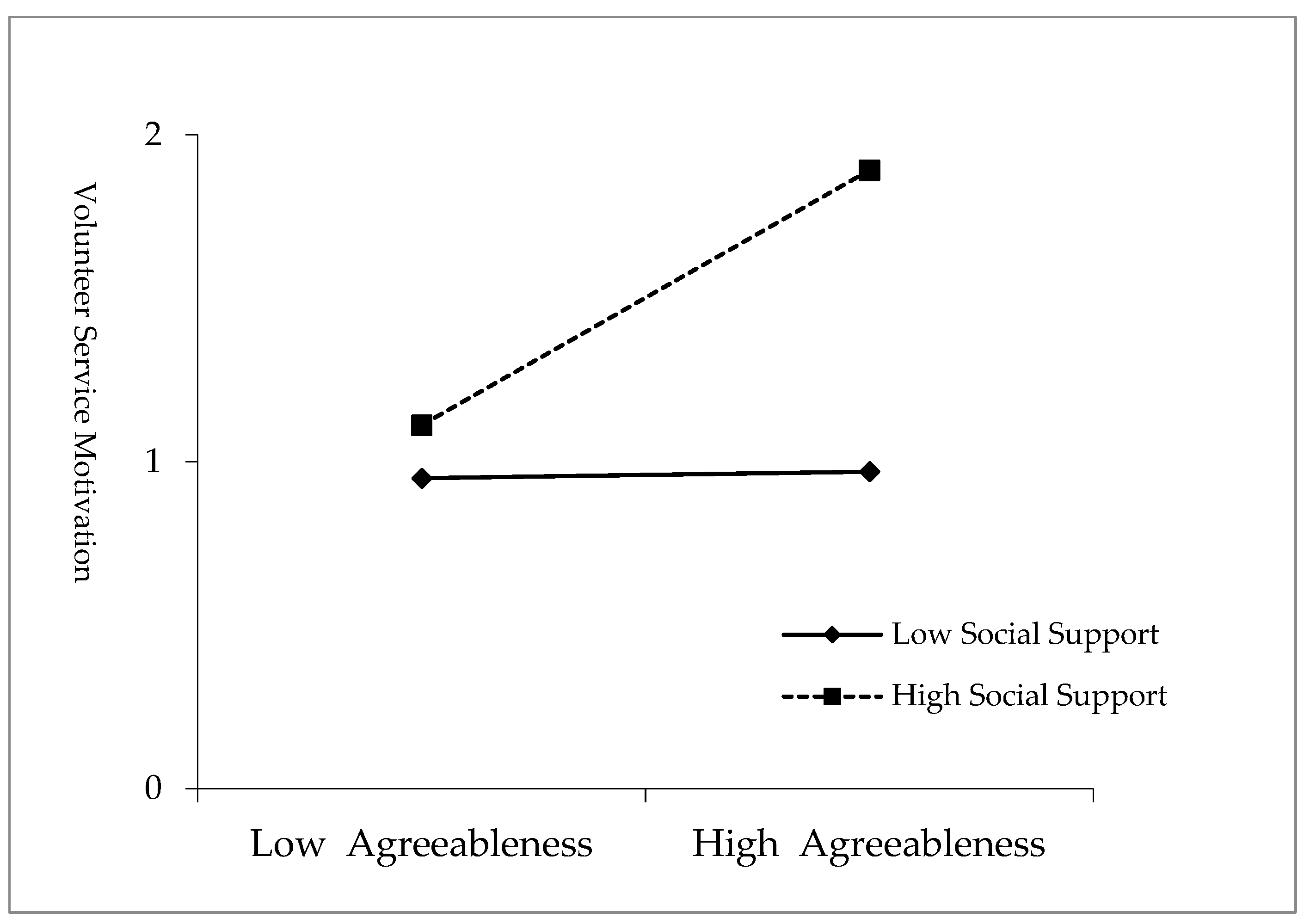

2.3. The Moderating Role of Social Support

3. Methods

3.1. Procedure and Participants

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Agreeableness Traits

3.2.2. Volunteer Service Motivation

3.2.3. Volunteer Service Behavior

3.2.4. Social Support

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analyses

4.2. Common Method Bias Analysis

4.3. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

4.4. Hypotheses and Model Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Recommendations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abuiyada, R. (2018). Students’ attitudes towards voluntary services: A study of Dhofar University. Journal of Sociology and Social Work, 6(1), 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, K. (2019). Predisposed to volunteer? Personality traits and different forms of volunteering. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 48(6), 1119–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguila, J. P., & Salvador, N. T. (2025). Sociological imagination and volunteerism of teacher education students at one state university in Batangas. Community and Social Development Journal, 26(1), 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L. S., West, S. G., & Reno, R. R. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar, H. (2019). Predicting participation in volunteering based on personality characteristics. Journal of Educational, Health and Community Psychology, 8(2), 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J. C., & Moore, L. F. (1978). The motivation to volunteer. Journal of Vvoluntary Aaction Rresearch, 7(3–4), 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, H., & Ross, S. D. (2009). Volunteer motivation and satisfaction. Journal of Vvenue and Event Management, 1(1), 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cady, S. H., Brodke, M., Kim, J. H., & Shoup, Z. D. (2018). Volunteer motivation: A field study examining why some do more, while others do less. Journal of Community Psychology, 46(3), 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canty-Mitchell, J., & Zimet, G. D. (2000). Psychometric properties of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support in urban adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology, 28(3), 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B., Hassan, N. C., & Omar, M. K. (2024). The impact of social support on burnout among lecturers: A systematic literature review. Behavioral Sciences, 14(8), 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlo, G., Okun, M. A., Knight, G. P., & de Guzman, M. R. T. (2005). The interplay of traits and motives on volunteering: Agreeableness, extraversion and prosocial value motivation. Personality and Iindividual Ddifferences, 38(6), 1293–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C., Jiang, J., Ji, S., & Hai, Y. (2022). Resilience and self-esteem mediated associations between childhood emotional maltreatment and aggression in Chinese college students. Behavioral Sciences, 12(10), 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. M., Kim, H. S., Mojaverian, T., & Morling, B. (2012). Culture and social support provision: Who gives what and why. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(1), 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Li, D., & Li, Y. (2023). Does volunteer service foster education for a sustainable future?—Empirical evidence from Chinese university students. Sustainability, 15(14), 11259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q. P., Wu, J. J., & Ruan, W. Q. (2021). What fascinates you? Structural dimension and element analysis of sensory impressions of tourist destinations created by animated works. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 26(9), 1038–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H., Lim, J., & Chiu, W. (2024). The effects of volunteer management and personality on quality of life and intention to donate in the context of compulsory volunteering: An environmental psychology approach. Sage Open, 14(2), 21582440241249887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y., Han, J., & Kim, H. (2023). Exploring key service-learning experiences that promote students’ learning in higher education. Asia Pacific Education Review, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clary, E. G., Snyder, M., Ridge, R. D., Copeland, J., Stukas, A. A., Haugen, J., & Miene, P. (1998). Understanding and assessing the motivations of volunteers: A functional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(6), 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Conway, J. M., & Lance, C. E. (2010). What reviewers should expect from authors regarding common method bias in organizational research. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(3), 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P. T., Jr., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Four ways five factors are basic. Personality and Individual Differences, 13(6), 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, J., Homberg, F., & Secchi, D. (2017). The public service-motivated volunteer devoting time or effort: A review and research agenda. Voluntary Sector Review, 8(3), 299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruce, T. M., & Moore, J. V. (2007). First-year students’ plans to volunteer: An examination of the predictors of community service participation. Journal of College Student Development, 48(6), 655–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, J. B., & McCrum-Gardner, E. (2007). Power, effect and sample size using GPower: Practical issues for researchers and members of research ethics committees. Evidence-Based Midwifery, 5(4), 132–137. Available online: https://sid.ir/paper/621760/en (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- De León, M. C. D., & Fuertes, F. C. (2007). Prediction of longevity of volunteer service: A basic alternative proposal. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 10(1), 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionigi, A., Casu, G., & Gremigni, P. (2020). Associations of self-efficacy, optimism, and empathy with psychological health in healthcare volunteers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 6001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harp, E. R., Scherer, L. L., & Allen, J. A. (2017). Volunteer engagement and retention: Their relationship to community service self-efficacy. Nonprofit and Vvoluntary Ssector Qquarterly, 46(2), 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattie, J. (2008). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F., & Preacher, K. J. (2010). Quantifying and testing indirect effects in simple mediation models when the constituent paths are nonlinear. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 45(4), 627–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J., Zhang, T., Wang, H., Chen, Z., & Liu, L. (2023). Intention patterns predicting college students’ volunteer service participation. Heliyon, 9(11), e21897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J. (2024). Youth volunteer services for red culture: Mechanisms and pathways to strengthen the sense of community for the Chinese nation. Academic Journal of Business & Management, 6(12), 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L., Wu, H., Zhang, Y., Zhang, F., Liao, L., Wu, X., Xu, J., Yao, Y., Wang, S., & Liu, Y. (2025). Motivations and strategies of voluntary service for urban home-based older adults provided by volunteers with nursing background: A qualitative study. BMC Nursing, 24(1), 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W., & Tang, J. (2024). The event attachment formation process of mega-event volunteers. Current Issues in Tourism, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. (2020). Harman’s single factor test in PLS-SEM: Checking for common method bias. Data Analysis Perspectives Journal, 2(2), 1–6. Available online: https://scriptwarp.com/dapj/2021_DAPJ_2_2/Kock_2021_DAPJ_2_2_HarmansCMBTest.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Kramer, M. W., Austin, J. T., & Hansen, G. J. (2021). Toward a model of the influence of motivation and communication on volunteering: Expanding self-determination theory. Management Communication Quarterly, 35(4), 572–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. J. (2012). Behavioral implications of public service motivation: Volunteering by public and nonprofit employees. The American Review of Public Administration, 42(1), 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. J., & Won, D. (2011). Attributes influencing college students’ participation in volunteering: A conjoint analysis. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 8(2), 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leisink, P. L., Knies, E., & van Loon, N. (2021). Does public service motivation matter? A study of participation in various volunteering domains. International Public Management Journal, 24(6), 865–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D., Ahmad, N. A., & Roslan, S. (2025). Perceived social support from parents, teachers, and friends as predictors of test anxiety in Chinese final-year high school students: The mediating role of academic buoyancy. Behavioral Sciences, 15(4), 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z., Ying, C., & Chen, J. (2024). The impact of volunteer service on moral education performance and mental health of college students. PLoS ONE, 19(4), e0294586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacNeela, P. (2008). The give and take of volunteering: Motives, benefits, and personal connections among Irish volunteers. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 19(2), 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, H. W., Coulter, R., & Fancourt, D. (2022). Relationships between volunteering, neighbourhood deprivation and mental wellbeing across four British birth cohorts: Evidence from 10 years of the UK household longitudinal study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maki, A., & Snyder, M. (2017). Investigating similarities and differences between volunteer behaviors: Development of a volunteer interest typology. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 46(1), 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manteli, M., & Galanakis, M. (2022). The new foundation of organizational psychology. Trait activation theory in the workplace: Literature review. Journal of Psychology Research, 12(1), 939–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, H. M., & Jones, S. R. (2004). Community service in the transition: Shifts and continuities in participation from high school to college. The Journal of Higher Education, 75(3), 307–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Q., Huang, J., & Yin, H. (2025). Emotions matter: Understanding the relationship between drivers of volunteering and participation. Journal of Social Service Research, 51(3), 678–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, C. W., & Allen, J. P. (1996). The effects of volunteering on the young volunteer. Journal of Primary Prevention, 17(2), 231–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, E., Warta, S., & Erichsen, K. (2014). College students’ volunteering: Factors related to current volunteering, volunteer settings, and motives for volunteering. College Student Journal, 48(3), 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Y., Park, A., & Suh, K. H. (2024). Psychological predictors of attitude toward integrated arts education among Chinese college students majoring in the arts. Behavioral Sciences, 14(10), 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiman, N., Fauzi, M. A., Norizan, N., Abdul Rashid, A., Tan, C. N. L., Wider, W., Ravesangar, K., & Selvam, G. (2024). Exploring personality traits in the knowledge-sharing behavior: The role of agreeableness and conscientiousness among Malaysian tertiary academics. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 16(5), 1884–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, J. C., Komarraju, M., Carter, M. Z., & Karau, S. J. (2017). Angel on one shoulder: Can perceived organizational support moderate the relationship between the Dark Triad traits and counterproductive work behavior? Personality and Individual Differences, 110, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, J. L., Brudney, J. L., Coursey, D., & Littlepage, L. (2008). What drives morally committed citizens? A study of the antecedents of public service motivation. Public Administration Review, 68(3), 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, J. R., & Aguinis, H. (2013). The too-much-of-a-good-thing effect in management. Journal of Management, 39(2), 313–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathakrishnan, B., Bikar Singh, S. S., & Yahaya, A. (2022). Perceived social support, coping strategies and psychological distress among university students during the COVID-19 pandemic: An exploration study for social sustainability in Sabah, Malaysia. Sustainability, 14(6), 3250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reizer, A., Harel, T., & Ben-Shalom, U. (2023). Helping others results in helping yourself: How well-being is shaped by agreeableness and perceived team cohesion. Behavioral Sciences, 13(2), 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smillie, L. D., Pickering, A. D., & Jackson, C. J. (2006). The new reinforcement sensitivity theory: Implications for personality measurement. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(4), 320–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snyder, M., Clary, E. G., & Stukas, A. A. (1999). The functional approach to volunteerism. In Why we evaluate (pp. 377–406). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stavrova, O., Evans, A. M., & van Beest, I. (2023). The effects of partner extraversion and agreeableness on trust. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 49(7), 1028–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stunkel, L., & Grady, C. (2011). More than the money: A review of the literature examining healthy volunteer motivations. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 32(3), 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W., Qi, Q., & Yuan, S. (2022). A moderated mediation model of academic supervisor developmental feedback and postgraduate student creativity: Evidence from China. Behavioral Sciences, 12(12), 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W., & Zhang, Y. (2023). More positive, more innovative: A moderated-mediation model of supervisor positive feedback and subordinate innovative behavior. Current Psychology, 42(33), 29682–29694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, A. N., & Hilmert, C. (2018). Social support as a comfort or an encouragement: A systematic review on the contrasting effects of social support on cardiovascular reactivity. British Journal of Health Psychology, 23(4), 1040–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tett, R. P., & Burnett, D. D. (2003). A personality trait-based interactionist model of job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(3), 500–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tett, R. P., Toich, M. J., & Ozkum, S. B. (2021). Trait activation theory: A review of the literature and applications to five lines of personality dynamics research. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 8(1), 199–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trombini, C., Jiang, W., & Kinias, Z. (2025). Receiving social support motivates long-term prosocial behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 197(4), 689–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmot, M. P., & Ones, D. S. (2022). Agreeableness and its consequences: A quantitative review of meta-analytic findings. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 26(3), 242–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windon, S., Robotham, D., & Echols, A. (2024). Importance of organizational volunteer retention and communication with volunteers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Community Development, 55(2), 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wondimu, H., & Admas, G. (2024). The motivation and engagement of student volunteers in volunteerism at the University of Gondar. Discover Global Society, 2(1), 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J., Yue, S., & Xiao, Z. (2024). How does perceived calling influence sustained volunteering intention? The role of volunteering norm and COVID-19 pandemic strength. SAGE Open, 14(2), 21582440241255948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X., Cai, X., He, J., & Peng, X. (2025). Promoting volunteer tourist service performance in protected area: The impacts of self-efficacy. Tourism Recreation Research, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | RMSEA | NFI | GFI | CFI | TLI | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four-factor model | 158.98 | 98 | 1.622 | 0.039 | 0.941 | 0.953 | 0.976 | 0.971 | 0.058 |

| Three-factor model | 456.29 | 101 | 4.518 | 0.093 | 0.831 | 0.845 | 0.862 | 0.836 | 0.093 |

| Two-factor model | 611.94 | 103 | 5.941 | 0.110 | 0.773 | 0.804 | 0.802 | 0.770 | 0.110 |

| Single-factor model | 1356.91 | 104 | 13.047 | 0.172 | 0.497 | 0.637 | 0.524 | 0.439 | 0.199 |

| Variables | Means | SD | Agreeableness | Social Support | Service Motivation | Service Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreeableness | 2.51 | 0.884 | 1 | |||

| Social Support | 2.62 | 0.906 | 0.464 ** | 1 | ||

| Service Motivation | 2.41 | 0.848 | 0.383 ** | 0.419 ** | 1 | |

| Service Behavior | 3.21 | 1.088 | 0.163 ** | 0.279 ** | 0.277 ** | 1 |

| Variables | Volunteer Service Motivation | Volunteer Service Behavior | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

| Gender | 0.128 ** | 0.045 | 0.069 | 0.068 | 0.037 | 0.025 |

| Grade | −0.048 | −0.100 * | −0.081 | 0.105 * | 0.086 | 0.113 * |

| Agreeableness | 0.387 *** | 0.200 *** | 0.143 ** | 0.042 | ||

| Volunteer Service Motivation | 0.263 *** | |||||

| Social Support | 0.270 *** | |||||

| Agreeableness × Social Support | 0.190 *** | |||||

| R2 | 0.019 | 0.159 | 0.267 | 0.016 | 0.035 | 0.093 |

| ΔR2 | 0.140 | 0.108 | 0.019 | 0.058 | ||

| F | 3.884 * | 25.442 *** | 29.300 *** | 3.227 * | 4.871 ** | 10.343 *** |

| Dependent Variable | Moderating Indirect Effect | Moderating Mediating Effect | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderator | Index | SE | 95% | Index | SE | 95% | |||

| LLCI | ULCI | LLCI | ULCI | ||||||

| Volunteer Service Behavior | Low Social Support | 0.0177 | 0.0220 | −0.0243 | 0.0633 | 0.0518 | 0.0236 | 0.0121 | 0.1035 |

| High Social Support | 0.1116 | 0.0361 | 0.0502 | 0.1926 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, C.; Su, W. The Impact of Agreeableness Trait on Volunteer Service Motivation and Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Study of Chinese College Students. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1308. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101308

Chen C, Su W. The Impact of Agreeableness Trait on Volunteer Service Motivation and Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Study of Chinese College Students. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1308. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101308

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Chen, and Weilin Su. 2025. "The Impact of Agreeableness Trait on Volunteer Service Motivation and Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Study of Chinese College Students" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 10: 1308. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101308

APA StyleChen, C., & Su, W. (2025). The Impact of Agreeableness Trait on Volunteer Service Motivation and Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Study of Chinese College Students. Behavioral Sciences, 15(10), 1308. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101308