Do Boys and Girls Evaluate Sexual Harassment Differently? The Role of Negative Emotions and Moral Disengagement

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Sexual Harassment Perception Among Adolescents

1.2. The Italian Context: Some Data

1.3. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

- The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory for Adolescent—Short Version (ISA; De Lemus et al., 2010). A subset of six items was selected based on item wording and their theoretical coverage of the three dimensions of Hostile Sexism. In particular, three items measured Hostile Sexism toward women (e.g., “Boys should exert control over who their girlfriends interact with”; α = 0.70) and 3 items measured Benevolent Sexism toward women (e.g., “Girls should be cherished and protected by boys”). Due to the low reliability, the Benevolent Sexism subscale was not used in the following analysis. The items were rated on a 6-point Likert-type scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (0) to “strongly agree” (5).

- The eight-item version of the Moral Disengagement in Sexual Harassment Scale (MDiSH; Page & Pina, 2018). Each item, one per moral disengagement mechanism, was adapted to the school context (e.g., “In a study place with a relaxed atmosphere, men cannot be blamed for “trying it on” with attractive girls when they get the chance”; α = 0.80). These items were rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree).

- The Sexual Harassment Definitions Questionnaire (SHDO; Foulis & McCabe, 1997). It consists of 10 scenarios of potential sexual harassment, including 5 same-gender harassers and 5 opposite-gender scenarios. For each scenario, participants were asked to indicate whether they considered it to be a case of sexual harassment (yes = 1; no = 0). Higher scores (range: 0–10) indicate a greater ability to recognize and label cases as sexual harassment.

- The Emotional Reactions to Harassment Scenarios (from Foulis & McCabe, 1997). For each of the 10 scenarios included in the SHDO (Foulis & McCabe, 1997), participants were also asked: “If you were [name of the protagonist], would you feel: flattered, annoyed, worried, appreciated, not bothered?”. Participants could select each of these five emotional reactions per scenario. Responses were coded dichotomously (1 = emotion selected; 0 = not selected). Although this emotional reaction question was included in the original SHDO questionnaire, the original article did not report any analyses of these responses.

- The Attitudes Toward Sexually Harassing Behavior (TSHI; Lott et al., 1982; α = 0.73) was used to assess respondents’ general attitudes toward SH. It contains 10 items (e.g., “It is only natural for a man to make sexual advances to a woman he finds attractive”) and measures on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Two items were reversed so low values indicate high tolerance for SH.

2.3. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. T-Tests and Correlations

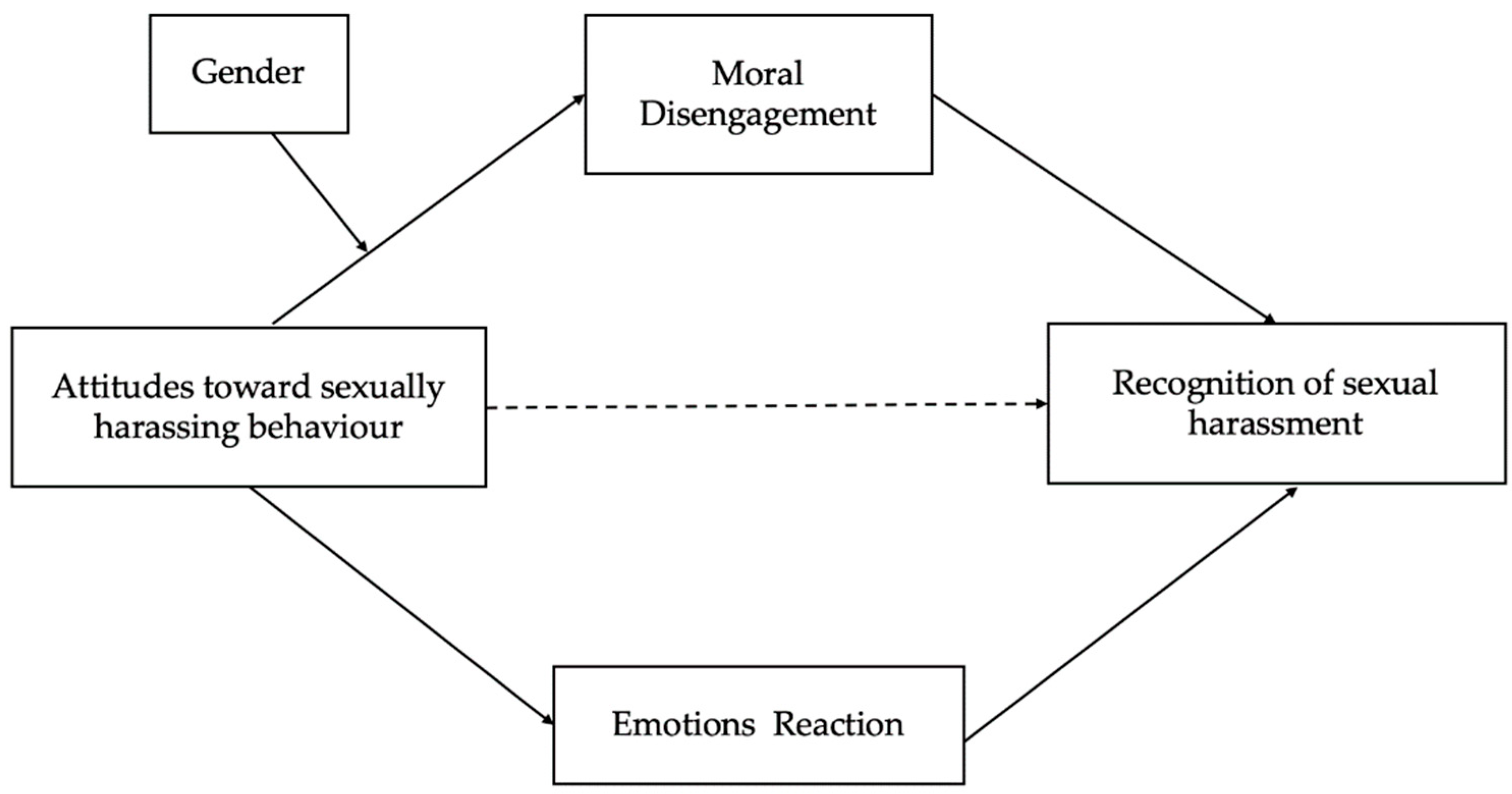

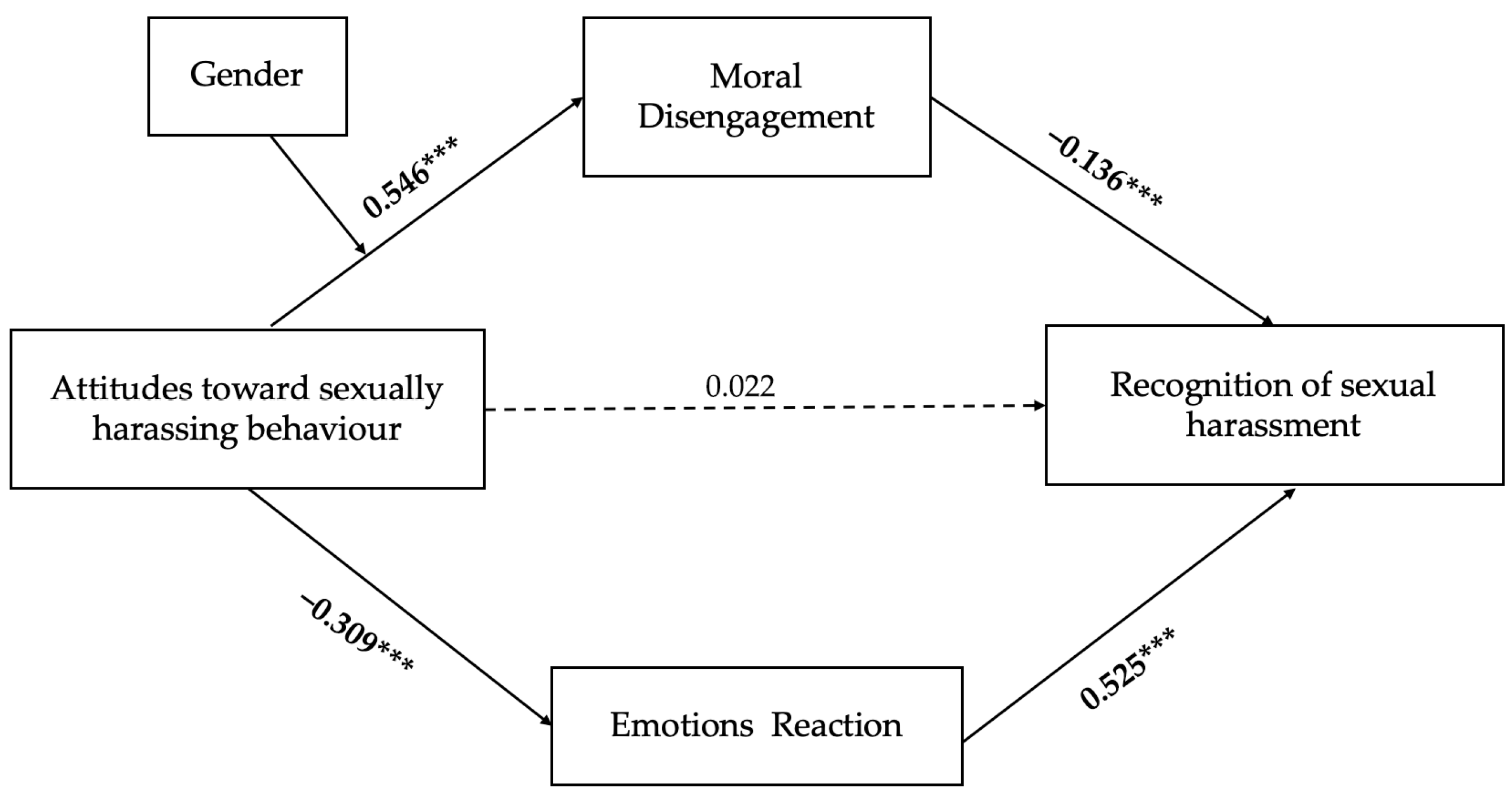

3.2. Mediation Model

3.3. Moderated Mediation Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Some data: the online exchange of intimate videos or photos occurs often in 14% of cases and rarely in 14%; sharing one’s intimate photos without consent occurs often in 6% of cases and rarely in 5% of cases. In essence, 54% of young people, with no difference between males and females, agree that “Those who send intimate photos always accept the risks they run, including that the photos may be shared with others”. |

References

- Arrojo, S., Martín-Fernández, M., Conchell, R., Lila, M., & Gracia, E. (2024). Validation of the adolescent dating violence victim-blaming attitudes scale. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 39(23–24), 5007–5032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, A., Vives-Cases, C., Davó-Blanes, C., Rodríguez-Blázquez, C., Forjaz, M. J., Bowes, N., DeClaire, K., Jaskulska, S., Pyżalski, J., Neves, S., Queirós, S., Gotca, I., Mocanu, V., Corradi, C., & Sanz-Barbero, B. (2021). Sexism and its associated factors among adolescents in Europe: Lights4Violence baseline results. Aggressive Behavior, 47(3), 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3(3), 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basile, K. C., Clayton, H. B., DeGue, S., Gilford, J. W., Vagi, K. J., Suarez, N. A., Zwald, M. L., & Lowry, R. (2020). Interpersonal violence victimization among high school students-youth risk behavior survey, United States, 2019. MMWR Supplements, 69(1), 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolduc, M.-L., Martin-Storey, A., & Paquette, G. (2022). Correlates of sexual harassment victimization among adolescents: A scoping review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 58, 101607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clear, E. R., Coker, A. L., Cook-Craig, P. G., Bush, H. M., Garcia, L. S., Williams, C. M., Lewis, A. M., & Fisher, B. S. (2014). Sexual harassment victimization and perpetration among high school students. Violence Against Women, 20(10), 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coop. (2025). La scuola degli affetti. Indagine sull’educazione alle relazioni. The School of Affections. Survey on Relationship Education. Available online: https://italiani.coop/uneducazione-alle-relazioni-necessaria/ (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Cuadrado-Gordillo, I., & Martín-Mora-Parra, G. (2022). Influence of cross-cultural factors about sexism, perception of severity, victimization, and gender violence in adolescent dating relationships. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 10356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lemus, S., Moya, M., & Glick, P. (2010). When contact correlates with prejudice: Adolescents’ romantic relationship experience predicts greater benevolent sexism in boys and hostile sexism in girls. Sex Roles, 63(3–4), 214–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DelGreco, M., Ebesu Hubbard, A. S., & Denes, A. (2021). Communicating by catcalling: Power dynamics and communicative motivations in street harassment. Violence Against Women, 27(9), 1402–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EIGE, European Institute for Gender Equality. (2024). Gender equality index. Available online: www.eige.europa.eu/gender-equality-index/2024/IT (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Eurobarometer. (2024). Gender stereotypes. European Union. ISBN 978-92-68-18800-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euronews. (2022). “The topic is still taboo”: Italy’s lack of sexual education in school. Available online: https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2022/07/12/the-topic-is-still-taboo-italys-lack-of-sexual-education-in-school (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Fagot, B. I., Rodgers, C. S., & Leinbach, M. D. (2012). Theories of gender socialization. In The developmental social psychology of gender (pp. 65–89). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Fuertes, A. A., Fernández-Rouco, N., Lázaro-Visa, S., & Gómez-Pérez, E. (2020). Myths about sexual aggression, sexual assertiveness and sexual violence in adolescent romantic relationships. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(23), 8744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, L. F., Gelfand, M. J., & Drasgow, F. (1995). Measuring sexual harassment: Theoretical and psychometric advances. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 17(4), 425–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fondazione Libellula. (2024). Senza confine—Le relazioni e la violenza tra adolescenti. Survey TEEN 2024. Available online: https://www.unistrapg.it/sites/default/files/docs/inclusione/docs/241106-survey-teen-2024-1.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Foulis, D., & McCabe, M. P. (1997). Sexual harassment: Factors affecting attitudes and perceptions. Sex Roles, 37(9–10), 773–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FRA, EIGE, Eurostat. (2024). EU gender-based violence survey—Key results. Experiences of women in the EU-27. Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Gini, G., Pozzoli, T., & Hymel, S. (2014). Moral disengagement among children and youth: A meta-analytic review of links to aggressive behavior. Aggressive Behavior, 40(1), 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1996). The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(3), 491–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2019). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, C., & Kearl, H. (2011). Crossing the line: Sexual harassment at school. American Association of University Women. [Google Scholar]

- Karami, A., Spinel, M. Y., White, C. N., Ford, K., & Swan, S. (2021). A systematic literature review of sexual harassment studies with text mining. Sustainability, 13(12), 6589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leaper, C., & Gutierrez, B. C. (2024). Sexism and gender-based discrimination. In Encyclopedia of adolescence (pp. 543–561). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipson, J. (2001). Hostile hallways: Bullying, teasing, and sexual harassment in school. AAUW Educational Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Lott, B., Reilly, M. E., & Howard, D. R. (1982). Sexual assault and harassment: A campus community case study. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 8(2), 296–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMaster, L. E., Connolly, J., Pepler, D. J., & Craig, W. M. (2002). Peer to peer sexual harassment in early adolescence: A developmental perspective. Development and Psychopathology, 14(1), 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obermann, M. (2011). Moral disengagement in self-reported and peer-nominated school bullying. Aggressive Behavior, 37(2), 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OnuItalia. (2023). Educazione sessuale scolastica: UNESCO pubblica rapporto, Italia tra le ultimate nazioni in Europa. Available online: https://onuitalia.com/2023/02/21/educazione-sessuale/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Page, T. E., & Pina, A. (2018). Moral disengagement and self-reported harassment proclivity in men: The mediating effects of moral judgment and emotions. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 24(2), 157–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peled-Laskov, R., Ein-Tal, I., & Cojocaru, L. (2020). How does it feel? Factors predicting emotions and perceptions towards sexual harassment. International Journal of Criminology and Sociology, 9, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramiro-Sánchez, T., Ramiro, M. T., Bermúdez, M. P., & Buela-Casal, G. (2018). Sexism in adolescent relationships: A systematic review. Psychosocial Intervention, 27, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, H. L., Foshee, V. A., Niolon, P. H., Reidy, D. E., & Hall, J. E. (2016). Gender role attitudes and male adolescent dating violence perpetration: Normative beliefs as moderators. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(2), 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, B. L., & Trigg, K. Y. (2004). Tolerance of sexual harassment: An examination of gender differences, ambivalent sexism, social dominance, and gender roles. Sex Roles, 50(7/8), 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakellari, E., Berglund, M., Santala, E., Bacatum, C. M. J., Sousa, J. E. X. F., Aarnio, H., Kubiliutė, L., Prapas, C., & Lagiou, A. (2022). The perceptions of sexual harassment among adolescents of four European countries. Children, 9(10), 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Save the Children. (2024). Violenza onlife: Indagine nazionale su percezione e vissuti della violenza online tra adolescenti. Available online: https://www.savethechildren.it/cosa-facciamo/pubblicazioni/violenza-onlife-indagine-ipsos-e-save-children (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Save the Children & IPSOS. (2024). Le ragazze stanno bene? Indagine sulla violenza di genere onlife in adolescenza. Available online: https://www.savethechildren.it/cosa-facciamo/pubblicazioni/le-ragazze-stanno-bene (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Sánchez-Jiménez, V., & Muñoz-Fernández, N. (2021). When are sexist attitudes risk factors for dating aggression? The role of moral disengagement in Spanish adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stonard, K. E., Bowen, E., Lawrence, T. R., & Price, S. A. (2014). The relevance of technology to the nature, prevalence and impact of adolescent dating violence and abuse: A research synthesis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 19(4), 390–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulla, F., Agueli, B., Lavanga, A., Logrieco, M. G. M., Fantinelli, S., & Esposito, C. (2025). Analysis of the development of gender stereotypes and sexist attitudes within a group of Italian high school students and teachers: A grounded theory investigation. Behavioral Sciences, 15(2), 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeting, H., Blake, C., Riddell, J., Barrett, S., & Mitchell, K. R. (2022). Sexual harassment in secondary school: Prevalence and ambiguities. A mixed methods study in Scottish schools. PLoS ONE, 17(2), e0262248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swim, J. K., & Cohen, L. L. (1997). Overt, covert, and subtle sexism: A comparison between the attitudes toward women and modern sexism scales. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(1), 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewska, P., & Schuster, I. (2021). Prevalence of teen dating violence in Europe: A systematic review of studies since 2010. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2021(178), 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Gea, E., Ortega-Ruiz, R., & Sánchez, V. (2016). Peer sexual harassment in adolescence: Dimensions of the sexual harassment survey in boys and girls. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 16(1), 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venäläinen, S. (2025). Omnipresence, victim-shaming and non-action: Young people’s views on sexual harassment in the #Metoo era. Violence Against Women. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wincentak, K., Connolly, J., & Card, N. (2017). Teen dating violence: A meta-analytic review of prevalence rates. Psychology of Violence, 7(2), 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, L., Baumler, E., Mytelka, C., Knutson, C., & Temple, J. R. (2025). Sexual harassment: Prevalence, predictors, and associated outcomes in late adolescence. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.29 | 1.09 | |||||

| 2.24 | 0.65 | 0.45 ** | ||||

| 2.44 | 1.11 | 0.62 ** | 0.55 ** | |||

| 4.72 | 1.68 | −0.36 ** | −0.31 ** | −0.42 ** | ||

| 0.95 | 1.10 | 0.37 ** | 0.39 ** | 0.44 ** | −0.29 ** | |

| 4.55 | 2.48 | −0.25 ** | −0.21 ** | −0.34 ** | 0.58 ** | −0.31 ** |

| Mean Scores (SD) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girls | Boys | t | p | Cohen’s D | |

| Hostile Sexism | 0.83 (0.80) | 1.88 (1.13) | 10.49 | <0.001 | 0.96 |

| Moral Disengagement | 1.91 (0.76) | 3.12 (1.12) | 12.47 | <0.001 | 0.93 |

| TSHI | 2.10 (0. 64) | 2.50 (0.60) | 6.18 | <0.001 | 0.62 |

| SHDO | 5.10 (2.43) | 3.90 (2.40) | −4.78 | <0.001 | 2.42 |

| Positive Emotion Reactions | 0.61 (0.92) | 1.36 (1.17) | 7.08 | <0.001 | 1.04 |

| Negative Emotion Reactions | 5.18 (1.60) | 4.16 (1.62) | −6.13 | <0.001 | 1.61 |

| β | B | SE | LLCI | ULCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSHI → SHDO | 0.022 | 0.086 | 0.201 | −0.309 | 0.480 |

| TSHI → Negative Emotion | −0.309 *** | −0.800 *** | 0.159 | −1.113 | −0.487 |

| TSHI → MD | 0.546 *** | 0.929 *** | 0.111 | 0.712 | 1.146 |

| Negative Emotion → SHDO | 0.525 *** | 0.775 *** | 0.065 | 0.648 | 0.902 |

| MD → SHDO | −0.136 ** | −0.306 ** | 0.123 | 0.013 | −0.547 |

| Indirect effects | |||||

| TSHI → MD → SHDO | −0.074 | −0.284 | 0.111 | −0.131 | −0.015 |

| TSHI → Negative Emotion → SHDO | −0.162 | −0.620 | 0.032 | −0.226 | −0.103 |

| Coefficient | SE | LLCI | ULCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome: Moral Disengagement | ||||

| TSHI | 1.595 *** | 0.271 | 1.061 | 2.129 |

| Gender | 0.351 | 0.372 | −0.381 | 1.084 |

| TSHI × Gender | −0.551 ** | 0.171 | −0.888 | −0.214 |

| Outcome: SHDO | Conditional indirect effects | |||

| EFFECT | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | |

| Male | −0.758 | 0.174 | −1.108 | −0.430 |

| Female | −0.358 | 0.088 | −0.546 | −0.204 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bosaia, L.; Garbi, G.; Berlin, E.; Lasagna, C.; Macrì, L.; Paradiso, M.N.; De Piccoli, N. Do Boys and Girls Evaluate Sexual Harassment Differently? The Role of Negative Emotions and Moral Disengagement. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1306. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101306

Bosaia L, Garbi G, Berlin E, Lasagna C, Macrì L, Paradiso MN, De Piccoli N. Do Boys and Girls Evaluate Sexual Harassment Differently? The Role of Negative Emotions and Moral Disengagement. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1306. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101306

Chicago/Turabian StyleBosaia, Laura, Gemma Garbi, Elisa Berlin, Camilla Lasagna, Loredana Macrì, Maria Noemi Paradiso, and Norma De Piccoli. 2025. "Do Boys and Girls Evaluate Sexual Harassment Differently? The Role of Negative Emotions and Moral Disengagement" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 10: 1306. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101306

APA StyleBosaia, L., Garbi, G., Berlin, E., Lasagna, C., Macrì, L., Paradiso, M. N., & De Piccoli, N. (2025). Do Boys and Girls Evaluate Sexual Harassment Differently? The Role of Negative Emotions and Moral Disengagement. Behavioral Sciences, 15(10), 1306. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101306