Uncovering the Relationship Between Buoyancy and Academic Achievement in Language Learning: The Multiple Mediating Roles of Burnout and Engagement

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. English Learning Buoyancy

2.2. English Learning Burnout

2.3. English Learning Engagement

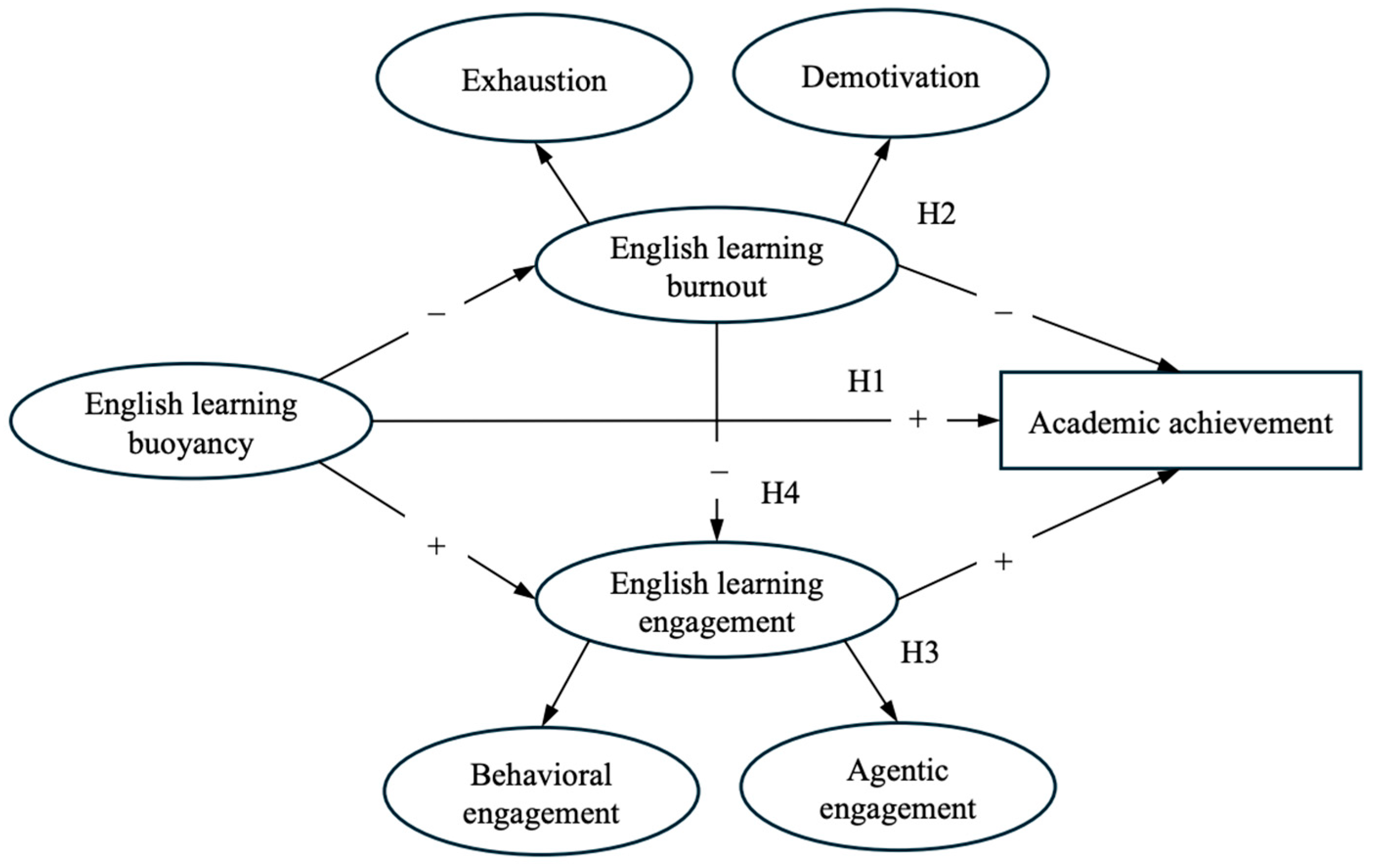

2.4. The Conceptual Model

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

3.2. Instruments

3.2.1. English Learning Buoyancy Scale

3.2.2. English Learning Burnout Scale

3.2.3. English Learning Engagement Scale

3.2.4. English Academic Achievement

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive and Correlation Analyses

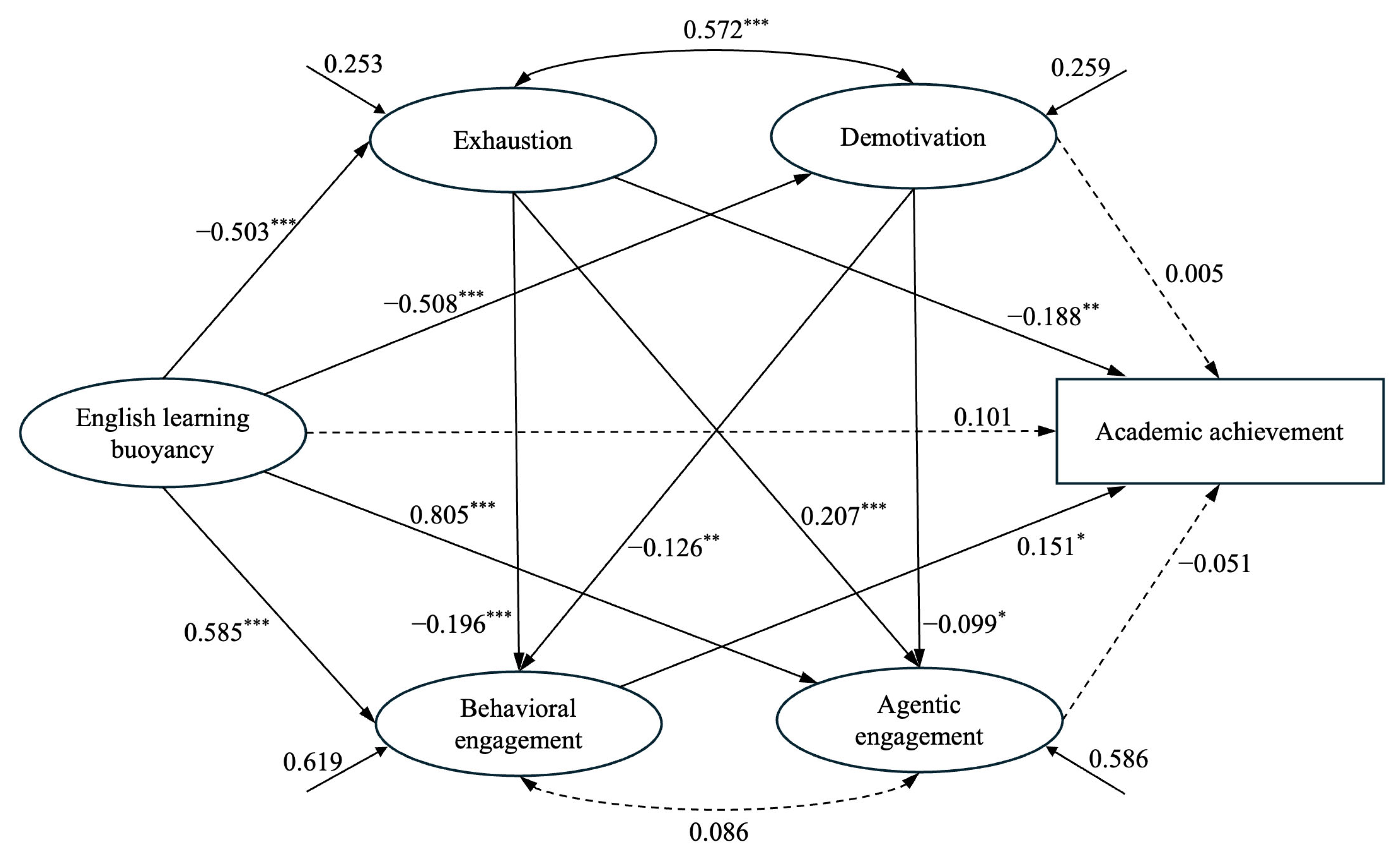

4.2. Structural Equation Modeling

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bai, B., & Wang, J. (2020). The role of growth mindset, self-efficacy and intrinsic value in self-regulated learning and English language learning achievements. Language Teaching Research, 27(1), 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, B., Zang, X., & Guo, W. (2025). Hong Kong students’ motivational beliefs and emotions in collaborative learning in ESL classrooms: Influences of actual and self-perceived English proficiency. Social Psychology of Education, 28, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bempechat, J., & Shernoff, D. J. (2012). Parental influences on achievement motivation and student engagement. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 315–342). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berweger, B., Born, S., & Dietrich, J. (2022). Expectancy–value appraisals and achievement emotions in an online learning environment: Within- and between-person relationships. Learning and Instruction, 77, 101546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnette, J., O’Boyle, E., VanEpps, E., Pollack, J., & Finkel, E. (2013). Mindsets matter: A meta-analytic review of implicit theories and self-regulation. Psychological Bulletin, 139(3), 655–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherniss, C. (1985). Stress, burnout, and the special services provider. Special Services in the Schools, 2(1), 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christenson, S. L., Reschly, A. L., & Wylie, C. (2012). Handbook of research on student engagement. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Derakhshan, A., & Fathi, J. (2023). Grit and foreign language enjoyment as predictors of EFL learners’ online engagement: The mediating role of online learning self-efficacy. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 33(4), 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakhshan, A., & Fathi, J. (2025). From boredom to buoyancy: Examining the impact of perceived teacher support on EFL learners’ resilience and achievement through a serial mediation model. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakhshan, A., & Noughabi, M. A. (2024). A self-determination perspective on the relationships between EFL learners’ foreign language peace of mind, foreign language enjoyment, psychological capital, and academic engagement. Learning and Motivation, 87, 102025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewaele, J., Chen, X., Padilla, A., & Lake, J. (2019). The flowering of positive psychology in foreign language teaching and acquisition research. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diert-Boté, I., & Moncada-Comas, B. (2024). Out of the comfort zone, into the learning zone: An exploration of students’ academic buoyancy through the 5-Cs in English-medium instruction. System, 124, 103385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörnyei, Z. (2019). Towards a better understanding of the L2 learning experience, the Cinderella of the L2 motivational self system. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 9(1), 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörnyei, Z., MacIntyre, P. D., & Henry, A. (2014). Motivational dynamics in language learning. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C. S. (2017). From needs to goals and representations: Foundations for a unified theory of motivation, personality, and development. Psychological Review, 124(6), 689–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J. S., & Wang, M. T. (2012). Part II commentary: So what? The influence of expectancy–value theory on practice and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 37(1), 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2020). From expectancy-value theory to situated expectancy-value theory: A developmental, social cognitive, and sociocultural perspective on motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 60, 101830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles (Parsons), J., Adler, T. F., Futterman, R., Goff, S. B., Kaczala, C. M., Meece, J. L., & Midgley, C. (1983). Expectancies, values, and academic behaviors. In J. T. Spence (Ed.), Achievement and achievement motives: Psychological and sociological approaches (pp. 75–146). Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Erakman, N., & Mede, E. (2018). Student burnout at English preparatory programs: A case study. International Journal of Educational Researchers, 9(3), 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, N., Yang, C., Kong, F., & Zhang, Y. (2024). Low-to mid-level high school first-year EFL learners’ growth language mindset, grit, burnout, and engagement: Using serial mediation models to explore their relationships. System, 125, 103397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farber, B. A. (1991). Crisis in education: Stress and burnout in the American teacher. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, E., & Hong, G. (2022). Engagement mediates the relationship between emotion and achievement of Chinese EFL learners. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 895594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 359(1449), 1367–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L. (2023). Social support in class and learning burnout among Chinese EFL learners in higher education: Are academic buoyancy and class level important? Current Psychology, 43, 5789–5803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L., & Qiu, Y. (2024). Contributions of psychological capital to the learning engagement of Chinese undergraduates in blended learning during the prolonged COVID-19 pandemic: The mediating role of learning burnout and the moderating role of academic buoyancy. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 39(2), 837–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladstone, J. R., Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2022). Situated expectancy-value theory, dimensions of engagement, and academic outcomes. In A. L. Reschly, & S. L. Christenson (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 57–76). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y., Xu, J., & Chen, C. (2022). Measurement of engagement in the foreign language classroom and its effect on language achievement: The case of Chinese college EFL students. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 61(3), 1225–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate data analysis (8th ed.). Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S., & Eerdemutu, L. (2025). Buoyancy and achievement in Japanese language learning: The serial mediation of emotions and engagement. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 34, 1483–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y. (2017). Mediating and being mediated: Learner beliefs and learner engagement with written corrective feedback. System, 69, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hirvonen, R., Putwain, D. W., Määttä, S., Ahonen, T., & Kiuru, N. (2020). The role of academic buoyancy and emotions in students’ learning-related expectations and behaviours in primary school. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(4), 948–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseinpour Kharrazi, F., & Ghanizadeh, A. (2023). The interplay among EFL learners’ academic procrastination, learning approach, burnout, and language achievement. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 33(5), 1213–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2009). The factorial validity of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey in China. Psychological Reports, 105(2), 394–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahedizadeh, S., Ghonsooly, B., & Ghanizadeh, A. (2019). Academic buoyancy in higher education. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 11(2), 162–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennett, H. K., Harris, S. L., & Mesibov, G. B. (2003). Commitment to philosophy, teacher efficacy, and burnout among teachers of children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 33(6), 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y., Tian, L., & Lou, N. M. (2024). From growth mindset to positive outcomes in L2 learning: Examining the mediating roles of autonomous motivation and engagement. System, 127, 103519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y., Dewaele, J., & MacIntyre, P. D. (2021). Reducing anxiety in the foreign language classroom: A positive psychology approach. System, 101, 102604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M. N., & Fallah, N. (2021). Academic burnout, shame, intrinsic motivation and teacher affective support among Iranian EFL learners: A structural equation modeling approach. Current Psychology, 40, 2026–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, R., Wang, Y., Derakhshan, A., & Muhanna, M. A. (2025). Do achievement emotions underlie L2 engagement? A mixed-methods multinational study on the role of achievement emotions in multilingual English learners’ behavioral, cognitive, and emotional engagement. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lakkavaara, A., Upadyaya, K., Tang, X., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2024). The role of stress mindset and academic buoyancy in school burnout in middle adolescence. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 21(6), 847–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen-Freeman, D., & Cameron, L. (2008). Complex systems and applied linguistics. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C., Zhang, L. J., & Jiang, G. (2021). Conceptualisation and measurement of foreign language learning burnout among Chinese EFL students. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 45(4), 906–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Duan, S., & Liu, H. (2023). Unveiling the predictive effect of students’ perceived EFL teacher support on academic achievement: The mediating role of academic buoyancy. Sustainability, 15(13), 10205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C., Wang, P., & Tai, S. J. D. (2016). An analysis of student engagement patterns in language learning facilitated by Web 2.0 technologies. ReCALL, 28(2), 104–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G. L., Zhao, X., & Yang, B. (2024). Unpacking the predictive effects of motivation, enjoyment, and self-efficacy on informal digital learning of LOTE: Evidence from French and German learners in China. System, 126, 103504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. (2024). Demystifying the relationship between parental investment in learners’ English learning and learners’ L2 motivational self system in the Chinese context: A Bourdieusian capital perspective. International Journal of Educational Development, 104, 102973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., & Cai, Y. (2025). Unveiling the relationship between students’ perceived support by significant others and academic achievement in English learning: The mediating roles of buoyancy and burnout. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., Elahi Shirvan, M., & Taherian, T. (2025a). Revisiting the relationship between global and specific levels of foreign language boredom and language engagement: A moderated mediation model of academic buoyancy and emotional engagement. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 15(1), 13–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., Jin, L., Han, X., & Wang, H. (2024a). Unraveling the relationship between English learning burnout and academic achievement: The mediating role of English learning resilience. Behavioral Sciences, 14, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., Li, T., Zheng, H., Li, Y., & Fan, J. (2025b). Exploring the relationship between students’ language learning curiosity and academic achievement: The mediating role of foreign language anxiety. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., Li, X., & Wang, X. (2025c). Students’ mindsets, burnout, anxiety and classroom engagement in language learning: A latent profile analysis. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., & Zhong, Y. (2022). English learning burnout: Scale validation in the Chinese context. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1054356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H., Zhu, Z., & Chen, B. (2024b). Unraveling the mediating role of buoyancy in the relationship between anxiety and EFL students’ learning engagement. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 132(1), 195–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y., Wu, D., & Wang, F. (2018). EFL students’ burnout in English learning: A case study of Chinese middle school students. Asian Social Science, 14(4), 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIntyre, P., & Gregersen, T. (2012). Emotions that facilitate language learning: The positive-broadening power of the imagination. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 2(2), 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, D., & Liu, Y. (2025). Bounce back to move forward: Self-efficacy, academic buoyancy, and emotional well-being of high-proficiency adult multilinguals in language classrooms. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A. J., & Marsh, H. W. (2008). Academic buoyancy: Towards an understanding of students’ everyday academic resilience. Journal of School Psychology, 46(1), 53–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, A. J., & Marsh, H. W. (2009). Academic resilience and academic buoyancy: Multidimensional and hierarchical conceptual framing of causes, correlates and cognate constructs. Oxford Review of Education, 35(3), 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C. (1998). A multidimensional theory of burnout. In C. L. Cooper (Ed.), Theories of organizational stress (pp. 68–85). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Occupational Behavior, 2, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2016). Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry, 15(2), 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, S. (2019). Language learner engagement: Setting the scene. In X. Gao (Ed.), Second handbook of English language teaching (pp. 643–660). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad Hosseini, H., Derakhshesh, A., Fathi, J., & Mehraein, S. (2024). Examining the relationships between mindfulness, grit, academic buoyancy and boredom among EFL learners. Social Psychology of Education, 27, 1357–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxford, R. L. (2016). Toward a psychology of well-being for language learners: The “EMPATHICS” vision. In P. D. MacIntyre, T. Gregersen, & S. Mercer (Eds.), Positive psychology in SLA (pp. 10–87). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Pekrun, R. (2000). A social-cognitive, control-value theory of achievement emotions. In J. Heckhausen (Ed.), Motivational psychology of human development: Developing motivation and motivating development (pp. 143–163). Elsevier Science. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R. (2006). The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educational Psychology Review, 18(4), 315–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R. (2024). Control-value theory: From achievement emotion to a general theory of human emotions. Educational Psychology Review, 36(3), 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R., Frenzel, A., Goetz, T., & Perry, R. (2007). The control-value theory of achievement emotions: An integrative approach to emotions in education. In P. A. Schutz, & R. Pekrun (Eds.), Emotion in education (pp. 13–36). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pekrun, R., & Perry, R. P. (2014). Control-value theory of achievement emotions. In R. Pekrun, & L. Linnenbrink-Garcia (Eds.), International handbook of emotions in education (pp. 130–151). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Philp, J., & Duchesne, S. (2016). Exploring engagement in tasks in the language classroom. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 36, 50–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putwain, D. W., Pekrun, R., Nicholson, L. J., Symes, W., Becker, S., & Marsh, H. W. (2018). Control–value appraisals, enjoyment, and boredom in mathematics: A longitudinal latent interaction analysis. American Educational Research Journal, 55(6), 1339–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putwain, D. W., & Wood, P. (2023). Riding the bumps in mathematics learning: Relations between academic buoyancy, engagement, and achievement. Learning and Instruction, 83, 101691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putwain, D. W., Wood, P., & Pekrun, R. (2022). Achievement emotions and academic achievement: Reciprocal relations and the moderating influence of academic buoyancy. Journal of Educational Psychology, 114(1), 108–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J. (2012). A self-determination theory perspective on student engagement. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 149–172). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J., & Tseng, C.-M. (2011). Agency as a fourth aspect of students’ engagement during learning activities. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(4), 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reschly, A. L., & Christenson, S. L. (2022). Jingle-jangle revisited: History and further evolution of the student engagement construct. In A. L. Reschly, & S. L. Christenson (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 3–24). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, H., McKinley, J., & Baffoe-Djan, J. (2020). Data collection research methods in applied linguistics. Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, J., Ainley, M., & Frydenberg, E. (2005). Schooling issues digest: Student motivation and engagement. Australian Government, Department of Education, Science and Training.

- Sadoughi, M., & Hejazi, S. (2023). Teacher support, growth language mindset, and academic engagement: The mediating role of L2 grit. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 77, 101251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadoughi, M., Hejazi, S. Y., & Lou, N. M. (2023). How do growth mindsets contribute to academic engagement in L2 classes? The mediating and moderating roles of the L2 motivational self system. Social Psychology of Education, 26, 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmela-Aro, K., & Upadyaya, K. (2020). School engagement and school burnout profiles during high school–the role of socio-emotional skills. The European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 17(6), 943–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W., Martínez, I., Pinto, A., Salanova, M., & Bakker, A. (2002). Burnout and engagement in university students. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 33(5), 464–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirom, A., & Melamed, S. (2006). A comparison of the construct validity of two burnout measures in two groups of professionals. International Journal of Stress Management, 13(2), 176–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, E. A. (2019). Engagement and motivation during childhood. In S. Hupp, & J. Jewell (Eds.), Encyclopedia of child and adolescent development (pp. 1–14). Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, E. A., Kinderman, T. A., & Furrer, C. J. (2009). A motivational perspective on engagement and disaffection: Conceptualization and assessment of children’s behavioral and emotional participation in academic activities in the classroom. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 69, 493–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, A., & Dewaele, J. M. (2023). The relationships between young FL learners’ classroom emotions (anxiety, boredom, & enjoyment), engagement, and FL proficiency. Applied Linguistics Review, 15(5), 2015–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ushioda, E. (2008). Motivation and good language learners. In C. Griffiths (Ed.), Lessons from good language learners (pp. 19–34). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinter, K. (2021). Examining academic burnout: Profiles and coping patterns among Estonian middle school students. Educational Studies, 47(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. C., Haertal, G. D., & Walberg, H. J. (1994). Educational resilience in inner cities. In M. C. Wang, & E. W. Gordon (Eds.), Educational resilience in inner-city America: Challenges and prospects (pp. 45–72). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X., & Hui, L. (2024). Buoyancy and engagement in online English learning: The mediating roles and complex interactions of anxiety, enjoyment, and boredom. System, 125, 103418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., & Guan, H. (2020). Exploring demotivation factors of Chinese learners of English as a foreign language based on positive psychology. Revista Argentina de Clinica Psicologica, 297(1), 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., & Liu, H. (2022). The mediating roles of buoyancy and boredom in the relationship between autonomous motivation and engagement among Chinese senior high school EFL learners. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 992279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Wu, H., & Wang, Y. (2024). Engagement and willingness to communicate in the L2 classroom: Identifying the latent profiles and their relationships with achievement emotions. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 46, 2175–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H., Wang, Y., & Wang, Y. (2024a). How burnout, resilience, and engagement interplay among EFL learners? A mixed-methods investigation in the Chinese senior high school context. Porta Linguarum Revista Interuniversitaria de Didáctica de las Lenguas Extranjeras, IX, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H., Zeng, Y., & Fan, Z. (2024b). Unveiling Chinese senior high school EFL students’ burnout and engagement: Profiles and antecedents. Acta Psychologica, 243, 104153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H. (2024). The role of positive learning emotions in sustaining cognitive motivation for multilingual development. System, 123, 103323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., & Liang, S. (2025). Classroom social climate and student engagement in English as a Foreign language learning: The mediating roles of academic buoyancy and academic emotions. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 34, 1123–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeager, D. S., Hanselman, P., Walton, G. M., Murray, J. S., Crosnoe, R., Muller, C., Tipton, E., Schneider, B., Hulleman, C. S., Hinojosa, C. P., Paunesku, D., Romero, C., Flint, K., Roberts, A., Trott, J., Iachan, R., Buontempo, J., Yang, S. M., Carvalho, C. M., … Dweck, C. S. (2019). A national experiment reveals where a growth mindset improves achievement. Nature, 573(7774), 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H. (2018). What motivates Chinese undergraduates to engage in learning? Insights from a psychological approach to student engagement research. Higher Education, 76, 827–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S., Hiver, P., & Al-Hoorie, A. (2018). Academic buoyancy: Exploring learners’ everyday resilience in the language classroom. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 40(4), 805–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalts, R., Green, N., Tackett, S., & Lubin, R. (2021). The association between medical students’ motivation with learning environment, perceived academic rank, and burnout. International Journal of Medical Education, 12, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T., Zhang, R., & Peng, P. (2024). The relationship between trait emotional intelligence and English language performance among Chinese EFL university students: The mediating roles of boredom and burnout. Acta Psychologica, 248, 104353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X., Liu, G. L., Eerdemutu, L., & Shirvan, M. E. (2025). Do shyness and emotions matter in shaping classroom engagement? A study of multilingual learners of Chinese in Thailand. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X., Sun, P. P., & Gong, M. (2023). The merit of grit and emotions in L2 Chinese online language achievement: A case of Arabian students. International Journal of Multilingualism, 21(3), 1653–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X., & Wang, D. (2024). Unpacking the antecedents of boredom and its impact on university learners’ engagement in languages other than English: A qualitative study in the distance online learning context. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 35(3), 1121–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M., & Wang, X. (2024). The influence of enjoyment, boredom, and burnout on EFL achievement: Based on latent moderated structural equation modeling. PLoS ONE, 19(9), e0310281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | M | SD | ELBuo | ELBur | Ex | De | ELE | BE | AE | AA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELBuo | 3.43 | 0.83 | — | |||||||

| ELBur | 2.30 | 0.77 | −0.522 ** | — | ||||||

| Ex | 2.14 | 0.84 | −0.490 ** | 0.903 ** | — | |||||

| De | 2.46 | 0.86 | −0.457 ** | 0.909 ** | 0.643 ** | — | ||||

| ELE | 3.48 | 0.72 | 0.816 ** | −0.482 ** | −0.419 ** | −0.454 ** | — | |||

| BE | 3.88 | 0.66 | 0.714 ** | −0.587 ** | −0.545 ** | −0.518 ** | 0.828 ** | — | ||

| AE | 3.09 | 0.96 | 0.726 ** | −0.315 ** | −0.249 ** | −0.321 ** | 0.922 ** | 0.547 ** | — | |

| AA | — | — | 0.255 ** | −0.291 ** | −0.306 ** | −0.223 ** | 0.243 ** | 0.292 ** | 0.161 ** | — |

| Path | β | Boot SE | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Direct effects | |||||

| Buoyancy→Ex | −0.503 | 0.045 | −0.607 | −0.426 | <0.001 |

| Buoyancy→De | −0.508 | 0.050 | −0.689 | −0.487 | <0.001 |

| Buoyancy→BE | 0.585 | 0.040 | 0.396 | 0.554 | <0.001 |

| Buoyancy→AE | 0.805 | 0.047 | 0.807 | 0.991 | <0.001 |

| Buoyancy→AA | 0.101 | 0.111 | −0.096 | 0.339 | 0.255 |

| Ex→BE | −0.196 | 0.042 | −0.238 | −0.070 | <0.001 |

| Ex→AE | 0.207 | 0.052 | 0.127 | 0.333 | <0.001 |

| Ex→AA | −0.188 | 0.084 | −0.384 | −0.049 | <0.01 |

| De→BE | −0.126 | 0.031 | −0.149 | −0.029 | <0.01 |

| De→AE | −0.099 | 0.051 | −0.201 | −0.001 | <0.05 |

| De→AA | 0.005 | 0.064 | −0.115 | 0.136 | 0.940 |

| BE→AA | 0.151 | 0.111 | 0.011 | 0.448 | <0.05 |

| AE→AA | −0.051 | 0.068 | −0.187 | 0.080 | 0.462 |

| Indirect Effects | |||||

| Buoyancy→Ex→AA | 0.095 | 0.044 | 0.026 | 0.201 | <0.05 |

| Buoyancy→De→AA | −0.003 | 0.038 | −0.082 | 0.069 | 0.897 |

| Buoyancy→BE→AA | 0.088 | 0.054 | 0.007 | 0.219 | <0.05 |

| Buoyancy→AE→AA | −0.041 | 0.062 | −0.170 | 0.072 | 0.427 |

| Buoyancy→Ex→BE→AA | 0.015 | 0.010 | 0.003 | 0.042 | <0.05 |

| Buoyancy→Ex→AE→AA | 0.005 | 0.009 | −0.008 | 0.026 | 0.363 |

| Buoyancy→De→BE→AA | 0.010 | 0.008 | 0.001 | 0.034 | <0.05 |

| Buoyancy→De→AE→AA | −0.003 | 0.005 | −0.018 | 0.003 | 0.270 |

| Total Effects | |||||

| English learning buoyancy→AA | 0.267 | 0.058 | 0.208 | 0.435 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cai, Y.; Liu, H. Uncovering the Relationship Between Buoyancy and Academic Achievement in Language Learning: The Multiple Mediating Roles of Burnout and Engagement. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1304. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101304

Cai Y, Liu H. Uncovering the Relationship Between Buoyancy and Academic Achievement in Language Learning: The Multiple Mediating Roles of Burnout and Engagement. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1304. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101304

Chicago/Turabian StyleCai, Yicheng, and Honggang Liu. 2025. "Uncovering the Relationship Between Buoyancy and Academic Achievement in Language Learning: The Multiple Mediating Roles of Burnout and Engagement" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 10: 1304. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101304

APA StyleCai, Y., & Liu, H. (2025). Uncovering the Relationship Between Buoyancy and Academic Achievement in Language Learning: The Multiple Mediating Roles of Burnout and Engagement. Behavioral Sciences, 15(10), 1304. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101304