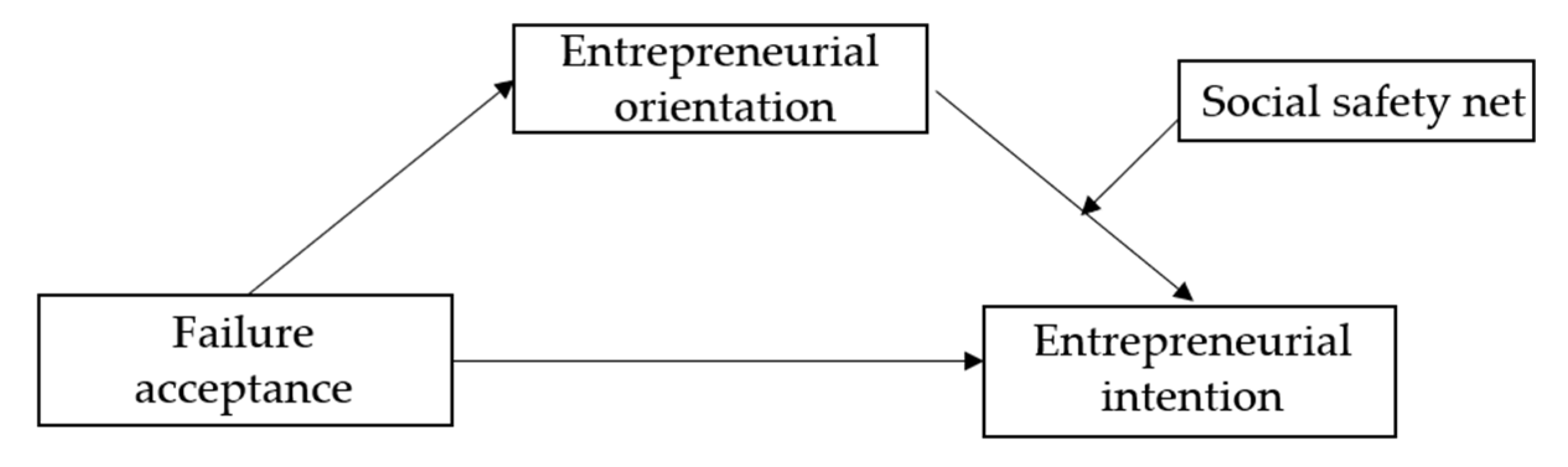

1. Introduction

The startup ecosystem in South Korea (Korea hereafter) stands at a significant turning point regarding the perception of failure. In the past, the dominant view was that failure was simply a negative outcome. However, recently, there is a rising movement to break away from this perspective and reinterpret failure as an essential process for growth and innovation. This change signifies a fundamental paradigm shift in startup culture, which has injected new vitality into the Korean startup ecosystem. Notably, evolution of the concept of failure acceptance is remarkable. That is, failure acceptance has transcended mere tolerance for failure and has adopted a more proactive and constructive meaning (

Hsu et al., 2017). Specifically, failure acceptance involves recognizing failures encountered during the entrepreneurial process as valuable learning experiences that facilitate personal and organizational growth (

Artinger & Powell, 2016). Individuals with high failure acceptance view failures as sources of new ideas, gaining unique insights from unsuccessful projects or concepts that they can leverage to develop more innovative solutions (

Larson, 2000). In this context, the role of entrepreneurial orientation is becoming more prominent. In South Korea’s startup environment, entrepreneurial orientation (EO) plays a crucial role in positively influencing the formation of entrepreneurial intention (EI) through failure acceptance. EO enhances individuals’ resilience and adaptability, empowering them to recover quickly from setbacks and seek new alternatives in the face of adversity (

Corner et al., 2017).

Korea’s entrepreneurial landscape has achieved quantitative growth; however, there remains room for improvement in terms of qualitative growth and sustainability. According to data from the Ministry of SMEs and Startups (where SME refers to small and medium-sized enterprises; this ministry is a government agency of South Korea established in 2017), technology startups increased by 4.7% in 2020 compared to the previous year; however, they accounted for only 23.3% of all startups. This shows that there is a lack of practical implementation of entrepreneurial spirit in Korean society. In this context, social safety nets are becoming increasingly important. When the culture and institutional environment recognize failure as a learning opportunity and support new challenges, psychological barriers to starting a business are lowered, leading to a surge in innovative startup activities. This perspective’s effectiveness is clearly demonstrated in global leading startup ecosystems. Most companies in Silicon Valley have an average of three failure experiences, and the culture of “fail fast, fail often” has become widely accepted (

Engel, 2015). Similarly, despite the high failure rate, the culture in Israel tolerates failure and encourages re-entrepreneurship, functioning as a social safety net. Institutional support also plays a crucial role. Silicon Valley’s “Pay it Forward” system and the Israeli government’s policies supporting entrepreneurs with failure experiences help lower the psychological barriers to their business and strengthen the process through which EO translates into actual startup activities (

Ester, 2017;

Chosun, 2019).

In this context, the entrepreneurial event model proposed by

Shapero and Sokol (

1982) provides a theoretical framework for explaining the process of forming EI. This model emphasizes three key elements: perceived desirability, perceived feasibility, and the propensity to act, which serve as useful constructs for understanding the roles of failure acceptance, EO, and social safety nets in this study. First, perceived desirability refers to the perception of the attractiveness of startup; in societies with high failure acceptance, starting a business may be perceived as a more desirable choice and may be viewed as a more desirable choice. Additionally, perceived feasibility reflects the belief in one’s ability to succeed in starting a business, and individuals with strong EO traits are likely to have higher perceived feasibility. Finally, propensity to act signifies the inclination to seize opportunities and take action. A social safety net that allows recovery from failure can further enhance an individual’s propensity to act, facilitating the transition to entrepreneurial behavior. Thus, elements of the entrepreneurial event model define the relationships among the key variables in this study and provide a theoretical basis for presenting the research model.

Meanwhile, research related to entrepreneurship offers valuable insights into EI and its influencing factors from various perspectives.

Liu et al. (

2011) indicated that individuals with EI may not necessarily translate those intentions into actual startups due to personal characteristics and the surrounding environment, emphasizing the need for research on the gap between intention and action.

Barba-Sánchez et al. (

2022) highlighted the importance of contextual factors by exploring external environmental influences on the formation of EI. Additionally,

He et al. (

2020) expanded the understanding of the role of failure by analyzing how past failure experiences impact subsequent EI.

While previous studies have made significant contributions to understanding EI and its influencing factors, there remain several important research gaps that this study aims to address. Most studies have focused on significant elements such as EI and behavior, the external environment, and experiences with failure. However, they largely overlooked the complex interaction between individual entrepreneurial characteristics and social context. While they acknowledged the importance of contextual factors, they did not thoroughly investigate how specific social structures and support mechanisms could influence the relationship between personal characteristics (such as acceptance of failure) and EI. To overcome these limitations, this study proposes a comprehensive approach to examining the factors affecting individuals’ EI in Korean society. Specifically, it investigates the effect of failure acceptance on EI while simultaneously exploring the mediating effect of EO and the moderating effect of social safety nets in this process. This approach extends previous studies by operationalizing the three core elements of the entrepreneurial event model into the specific variables of failure acceptance, EO, and social safety nets, and it comprehensively considers the relational influences among them. This aspect of the study offers a more nuanced understanding of the EI formation process by investigating how broader societal support structures can influence the relationship between individual traits and EI.

The research results are expected to provide a more in-depth understanding of the startup ecosystem in Korean society, suggest customized startup support policy directions that can be applied flexibly to individuals and situations, and ultimately contribute to startup activation and economic innovation.

4. Research Methods

4.1. Data Analysis

This study’s sample consisted of individuals aged 20 years and above who are employed in Korea. The research was conducted through an online survey over a two-month period from July to September 2023. A total of 286 questionnaires were collected, and 282 surveys were used for the final analysis after excluding four that had many missing values or insincere responses.

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the research subjects.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 27.0 and Macro 4.1 software, and the specific analysis methods are as follows. First, frequency analysis was conducted to identify the research participants’ demographic characteristics. Next, an exploratory factor analysis was performed to evaluate the validity of the measurement tools, and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated to examine the reliability of the measurement items. Descriptive statistical analysis and Pearson’s correlation analysis were conducted to confirm the levels of major variables and analyze the correlations between the variables. Additionally, confirmatory factor analysis was performed to verify convergent and discriminant validity, and factor loadings, average variance extracted (AVE), and concept reliability were calculated. For the mediation effect test, 2000 bootstrapping iterations were used, and multiple regression analysis was applied for the moderation effect test. All statistical significance was judged at a significance level of 0.05.

4.2. Questionnaire Composition

Table 2 presents the questionnaire composition for this study. To measure failure acceptance, this study followed the methods of

Lang and Fries (

2006) and

Boyd and Gumpert (

1983) to measure the fear of failure, which was reverse-scored. To measure the EO, we adopted the three dimensions of innovation, risk-taking, and proactiveness suggested by

Miller (

1983), and modified and used the scale of

Covin and Slevin (

1988), which is currently the most widely used in entrepreneurship research. In addition, the items used by

Lee (

2016) and

An and Chung (

2021) were used to measure awareness of the social safety net, and the measurement tool developed and used by

Crant (

1996) was used to measure EI.

4.3. Validity and Reliability of the Measurement Tool

An exploratory factor analysis was performed to evaluate the factor structure and validity of the measurement tool. Principal component analysis was applied as a factor extraction method, and varimax, a type of orthogonal rotation, was used as a factor rotation method. If the factor loading of an item was 0.4 or higher, it was judged to belong to the corresponding factor (

Ford et al., 1986), and the reliability of the variables derived through factor analysis was evaluated by the items’ internal fit coefficient. A coefficient being 0.6 or higher was interpreted as acceptably reliable (

Nunnally, 1978).

The exploratory factor analysis indicated that item six of EO did not meet the minimum factor loading criteria; thus, this item was removed, and the exploratory factor analysis was conducted again.

Table 3 presents the final analysis results. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure, which determines the adequacy of the sample size, was 0.800, which is higher than the minimum standard of 0.6; moreover, Bartlett’s test of sphericity, which determines whether the matrix is a unit matrix, was significant with the 0.05 significance level. This confirmed that the collected data were suitable for the exploratory factor analysis.

Six factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.0 were extracted, and each factor’s explanatory power was as follows: failure acceptance, 12.34%; innovativeness, 15.30%; risk-taking propensity, 8.82%; proactiveness, 10.87%; perception of social safety net, 14.57%; and EI, 14.85%. All items showed factor loadings greater than 0.4, and the internal consistency coefficients (Cronbach’s alpha) were 0.77 for failure acceptance, 0.81 for innovativeness, 0.74 for risk-taking propensity, 0.73 for proactiveness, 0.89 for perception of social safety net, and 0.89 for EI, confirming good validity and reliability of the measurement tool.

4.4. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

Table 4 presents the results of the descriptive statistics and correlations of the main variables in this study. To verify the general tendencies of the main variables and the assumption of normality, we calculated the mean and standard deviation, as well as checked the skewness and kurtosis values. The variables’ means were as follows: failure acceptance, 2.84; EO, 3.52; innovativeness, 3.60; risk taking, 3.60; proactiveness, 2.98; social safety net, 2.62; and EI, 3.17. The range of skewness for the variables was from −0.57 to 0.16, and the range of kurtosis was from −0.62 to 1.04. As the skewness was less than 3 and kurtosis less than 7, we confirmed that all variables satisfied the assumption of normal distribution (

Kline, 2023).

Furthermore, Pearson’s correlation analysis examined the relationships between the main variables, showing that failure acceptance had positive correlations with EO (r = 0.23, p < 0.001), innovativeness (r = 0.12, p < 0.05), risk taking (r = 0.22, p < 0.001), proactiveness (r = 0.23, p < 0.001), and social safety net (r = 0.13, p < 0.05). Moreover, EO showed a positive correlation with EI (r = 0.59, p < 0.001). However, the relationships between failure acceptance and EI, between EO and perception of social safety net, and between social safety net and EI were not significant. Additionally, we confirmed that there was no multicollinearity issue, as the variance inflation factor values for failure acceptance, EO, and social safety net were all below 10.

4.5. Measurement Model Testing

To verify the measurement model’s convergent and discriminant validity, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis. To assess the model’s fit, we examined the chi-square test statistic, incremental fit index (IFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), comparative fit index (CFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). The minimum criteria for acceptable model fit are IFI, TLI, and CFI values above 0.9 and RMSEA below 0.10 (

Bentler, 1990;

Browne & Cudeck, 1992). The model fit indices were IFI = 0.965, TLI = 0.951, CFI = 0.964, and RMSEA = 0.065, indicating an acceptable model fit.

Table 5 presents the standardized regression coefficients, AVE, and construct reliability (CR). Convergent validity is considered satisfactory when the standardized regression coefficients and AVE are above 0.5 and CR is above 0.7 (

Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). In this study, the standardized regression coefficients ranged from 0.61 to 0.92, AVE from 0.52 to 0.73, and CR from 0.77 to 0.89, confirming that convergent validity was established.

Discriminant validity is verified using the HTMT (heterotrait/monotrait ratio of correlations) method. In HTMT, the correlation between two different latent variables is evaluated. For this purpose, the correlations between items or sub-factors belonging to each latent variable are calculated, and the relationship between the two latent variables is measured through the ratio of these correlations. In this method, discriminant validity is considered satisfactory if the HTMT between latent variables is less than 0.85 (

Henseler et al., 2015). As shown in

Table 6, the HTMT among all latent variables is less than 0.85, confirming that discriminant validity is proven.

4.6. Hypothesis Testing

4.6.1. Verification of the Mediating Effect of Entrepreneurial Orientation

To test the mediating effect of EO on the relationship between failure acceptance and EI, we conducted an analysis using Macro Model 4 (

Hayes, 2015). Gender, age, education level, employment contract type, and tenure were set as control variables.

Table 7 presents the results of the analysis.

In the direct effects, gender (B = 0.23, confidence interval [CI] = 0.07~0.38), education level (B = 0.41, CI = 0.20~0.62), employment contract type (B = 0.28, CI = 0.06~0.51), and failure acceptance (B = 0.20, CI = 0.11~0.30) showed positive effects on EO. Specifically, men compared to women, those with a bachelor’s degree or higher compared to those without, full-time employees compared to contract workers, and those with higher compared to lower failure acceptance showed higher levels of EO. Therefore, Hypothesis 1, which posited that failure acceptance would have a positive effect on EO, was supported.

Additionally, gender (B = 0.36, CI = 0.14~0.58), education level (B = 0.44, CI = 0.14~0.75), tenure (B = 0.27, CI = 0.06~0.48), and EO (B = 0.93, CI = 0.77~1.10) showed positive effects on EI, while failure acceptance did not have a significant effect. This indicates that men compared to women, those with a bachelor’s degree or higher compared to those without, those with five or more years of tenure compared to those with less, and those with higher EO showed higher EI. Consequently, Hypothesis 3, which stated that EO would have a positive effect on EI, was supported, while Hypothesis 2, which proposed that failure acceptance would have a positive effect on EI, was rejected.

Regarding the indirect effects, the indirect path from failure acceptance to EI through EO was found to be significant (B = 0.19, CI = 0.09~0.29). This indicates a full mediation effect, where failure acceptance does not influence EI directly but only indirectly through EO. Therefore, Hypothesis 4, which posited that EO would mediate the relationship between failure acceptance and EI, was supported.

4.6.2. Verification of the Moderating Effect of the Social Safety Net

To test the moderating effect of the social safety net on the relationship between EO and EI, we conducted an analysis using Macro Model 1 (

Hayes, 2015). Gender, age, education level, employment contract type, and tenure were set as control variables. To avoid multicollinearity issues, the independent variable and moderator variable were mean-centered.

Table 8 presents the results.

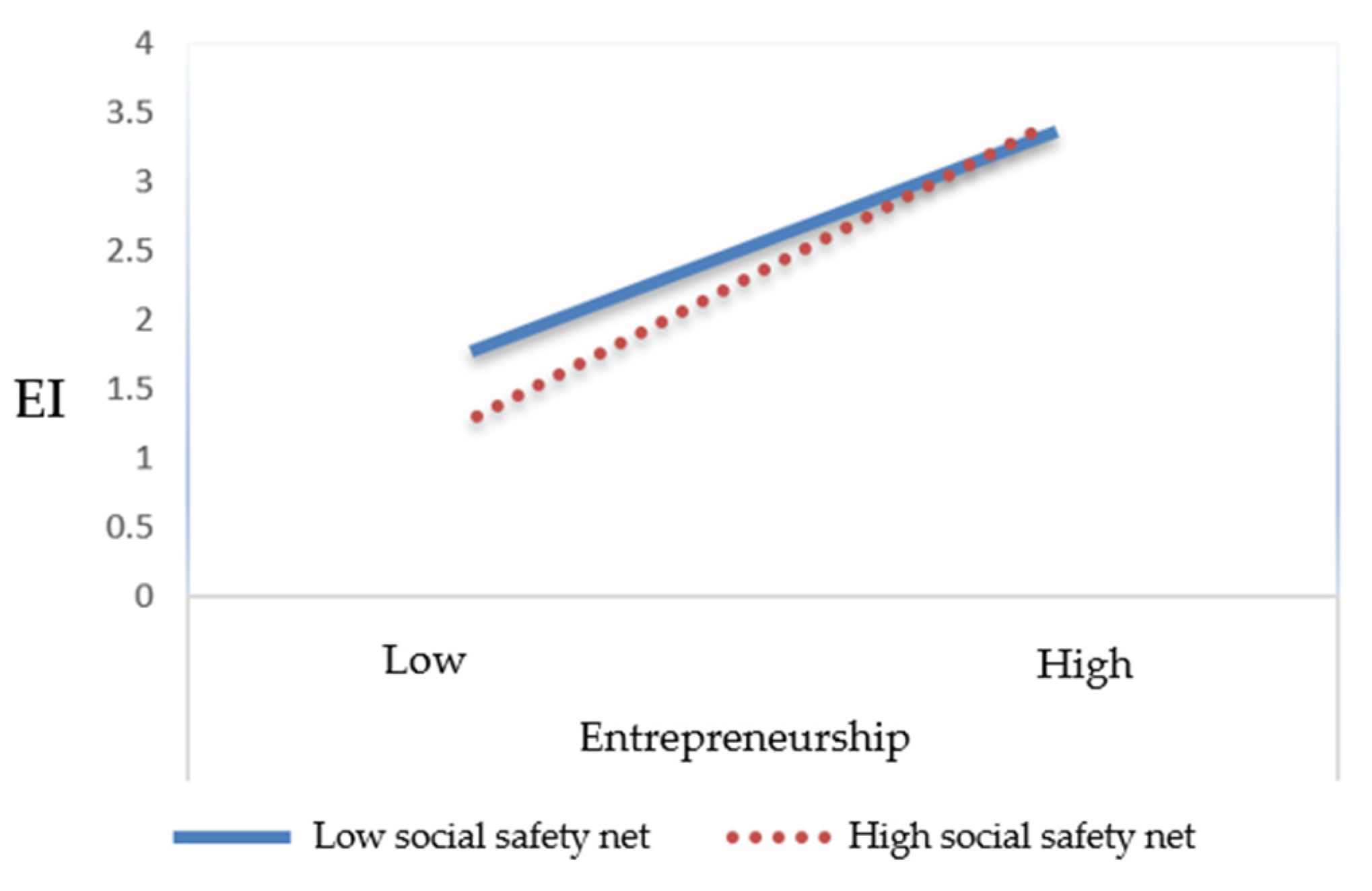

The analysis results showed that the interaction term between EO and perception of social safety net (B = 0.13, CI = 0.04~0.22) was significant. This confirms that the perception of social safety net moderates the relationship between EO and EI. Therefore, Hypothesis 5, which posited that the perception of social safety net moderates the relationship between EO and EI, was supported.

A simple slope analysis was conducted to determine the significance of the effect of EO on EI according to the level of the social safety net. Specifically, the effect of EO on EI was estimated at points ±1 standard deviation from the mean of the social safety net. As shown in

Table 9 and

Figure 2, when the perception of the social safety net was high, the increase in EI was greater as EO increased. Conversely, when the perception of the social safety net was low, the degree to which EI increased as EO increased was relatively lower.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Key Findings

The main results and discussions of this study are as follows.

First, failure acceptance was found to have a positive (+) effect on EO, supporting Hypothesis 1 and confirming previous research (

Ferrary & Granovetter, 2009). This finding suggests that entrepreneurs with high failure acceptance maintain a positive attitude toward overcoming failure and exploring new opportunities rather than fearing it. As a result, the overall level of EO among founders is enhanced, which serves to further strengthen the motivation and capabilities for entrepreneurial activities.

Second, EO was confirmed to have a positive (+) effect on EI. This supports Hypothesis 3 and aligns with the research findings (

Huang et al., 2021;

Shi et al., 2020). Individuals with high EO actively pursue creative and innovative ideas and have a stronger tendency to recognize business opportunities and put them into practice. In particular, entrepreneurs with high EO clearly demonstrate EI by taking risks and challenging new markets. This is an important result confirming that EO is a key factor in stimulating EI.

Third, failure acceptance was found to have a full mediating effect on EI through EO, supporting Hypothesis 4. In other words, the attitude of accepting failure alone does not increase EI directly but does so indirectly by strengthening EO. This indicates a complex process where the attitude of accepting failure as a positive experience enhances the entrepreneur’s spirit of challenge and creativity, ultimately leading to EI. These results provide an important implication that failure acceptance plays a crucial role in the entrepreneurial process, but its influence is manifested through the medium of EO.

Fourth, the social safety net was found to moderate the relationship between EO and EI, supporting Hypothesis 5. This suggests that when there is a social safety net that can minimize losses from entrepreneurial failure, the positive attitude towards EO is further enhanced. Thus, the existence of a social safety net plays an important role in providing psychological stability, allowing entrepreneurs to take more risks and attempt EO.

5.2. Implications

5.2.1. Academic Implications

The academic implications are as follows.

First, this study identified the full mediating effect of EO in the relationship between failure acceptance and EI. It revealed that failure acceptance does not influence EI directly but indirectly through EO. This clarified the mechanism by which failure acceptance strengthens EO, and enhanced EO increases EI. Specifically, this study empirically verified the process by which the attitude of not fearing failure reinforces entrepreneurial characteristics such as innovativeness, risk taking, and proactiveness, which in turn lead to increased EI. These findings provide a more sophisticated understanding of the EI formation process and emphasize the importance of failure acceptance.

Second, this study has academic significance as it expanded and concretized

Shapero and Sokol’s (

1982) entrepreneurial event model, which explains the EI formation process, to fit the context of this research. The abstract concepts in the existing model, such as “perceived desirability”, “perceived feasibility”, and “propensity to act”, were operationalized into measurable variables such as failure acceptance, EO, and perception of social safety nets. This expanded the practical applicability of the existing theory and strengthened the theoretical foundation of entrepreneurship research.

Third, the study verified the impact of the interaction between individual psychological characteristics (EO) and environmental factors (social safety net) on EI. These results emphasized the importance of an integrated consideration of individuals and the environment in entrepreneurship research, and they provided a new perspective on the role of social safety nets in creating an entrepreneurial ecosystem.

5.2.2. Practical Implications

The practical implications of this study’s results are as follows.

The fact that Korean workers’ tolerance for failure does not affect their intention to start a business directly but rather indirectly through their entrepreneurial spirit reflects the country’s unique entrepreneurial culture. It suggests that Korea’s economic growth has been achieved through bold challenges based on the entrepreneurial spirit of outstanding entrepreneurs. However, this entrepreneurial spirit has been gradually weakening in the Korean economy lately, which may weaken the spirit of challenge for starting a business and hinder economic growth. It seems that the anti-business sentiment prevalent throughout society, the fear of failure, and a culture of preferring stable jobs are discouraging the young generation’s will to start a business. In addition, factors that hinder business activities, such as excessive regulations and high tax burdens, are contributing to the weakening of entrepreneurial spirit. Therefore, various activities and efforts at the corporate, university, and national levels are necessary to strengthen the entrepreneurial spirit. Specifically, companies should activate internal entrepreneurship programs and support employees with innovative ideas. In particular, large corporations can foster their employees’ creativity and spirit of challenge through in-house venture systems. Universities need to strengthen entrepreneurship education and expand programs that provide students with real-world entrepreneurial experiences. For example, we can encourage students’ entrepreneurial spirit by activating startup clubs, hosting startup competitions, and operating incubation centers. Finally, the government should expand startup support policies and ease regulations to activate the startup ecosystem. We can reduce the burden of startups and encourage the spirit of challenge by providing tax benefits, startup funding support, and opportunities for re-challenge in case of failure. Through these multifaceted efforts, we can activate Korea’s startup ecosystem and maintain the momentum of economic growth.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

The limitations of this study are as follows.

First, this study is based on a cross-sectional analysis using data collected at a single time point. This approach is limited in capturing the dynamic relationships and changes over time between failure acceptance, EO, and EI, thus limiting the ability to clearly identify causal relationships between variables. Future research needs to overcome this limitation through longitudinal research designs using time-series data. For example, regular data collection over a certain period for a specific group can be conducted to observe the changing trends in the formation of EI. This will allow for a more accurate understanding of the variability of each variable over time, the dynamic patterns of interaction between variables, and long-term causal relationships.

Second, this study was conducted within a specific cultural context and did not fully consider the impact of cultural differences on the results. Future research must explore the influence of the cultural context on the process of EI formation through comparative studies in various cultural settings.

Third, various external factors that could influence EI were not fully controlled for in this study. In particular, economic conditions, changes in government policies, and industry trends can significantly impact an individual’s entrepreneurial decision-making process. Therefore, thoroughly incorporating these factors remains a challenge for future research.