The Relationship Between Mental Health Literacy and Social Well-Being: A Longitudinal Study in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Social Economic Status

2.2.2. Mental Health Literacy

2.2.3. Social Well-Being

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Result

3.1. The Common Method Deviation Test

3.2. Descriptive and Correlation Analysis

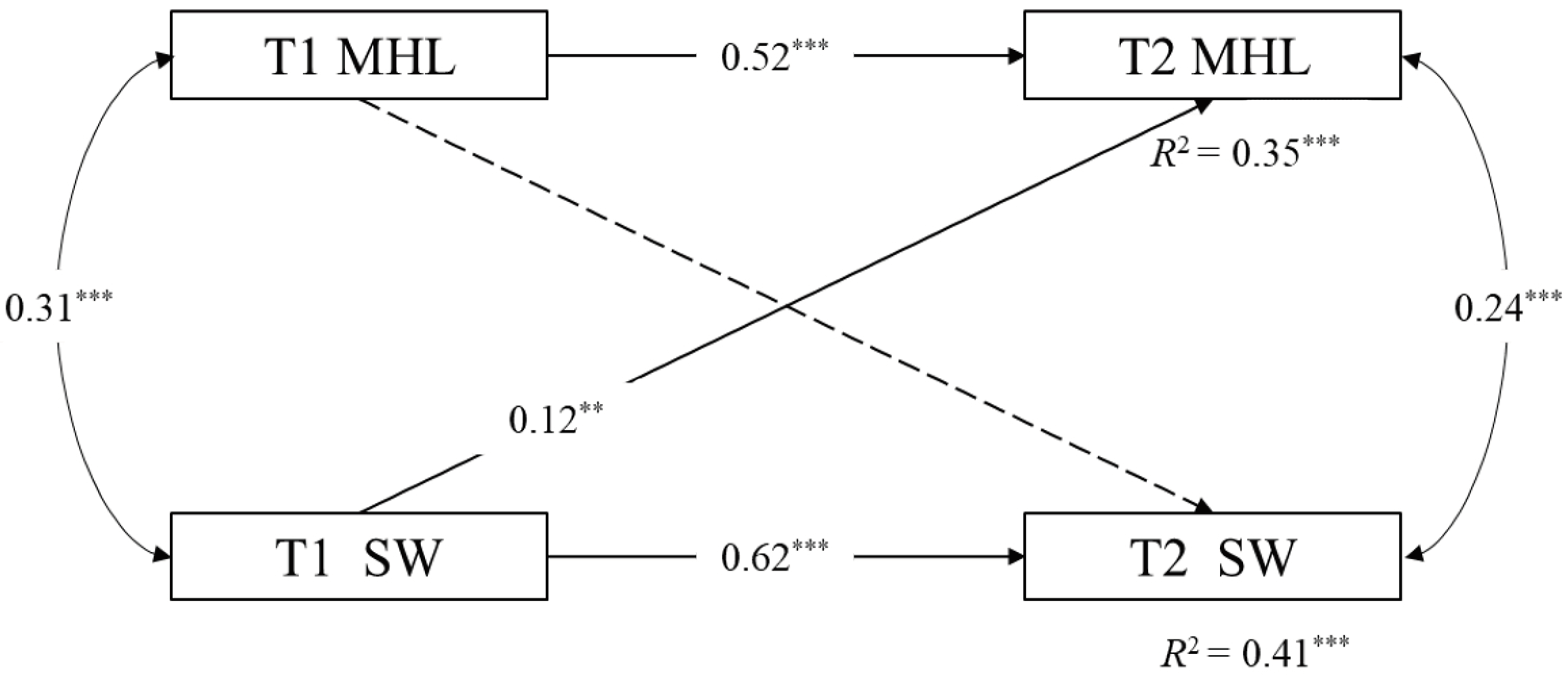

3.3. Longitudinal Cross-Lagged Model Analysis

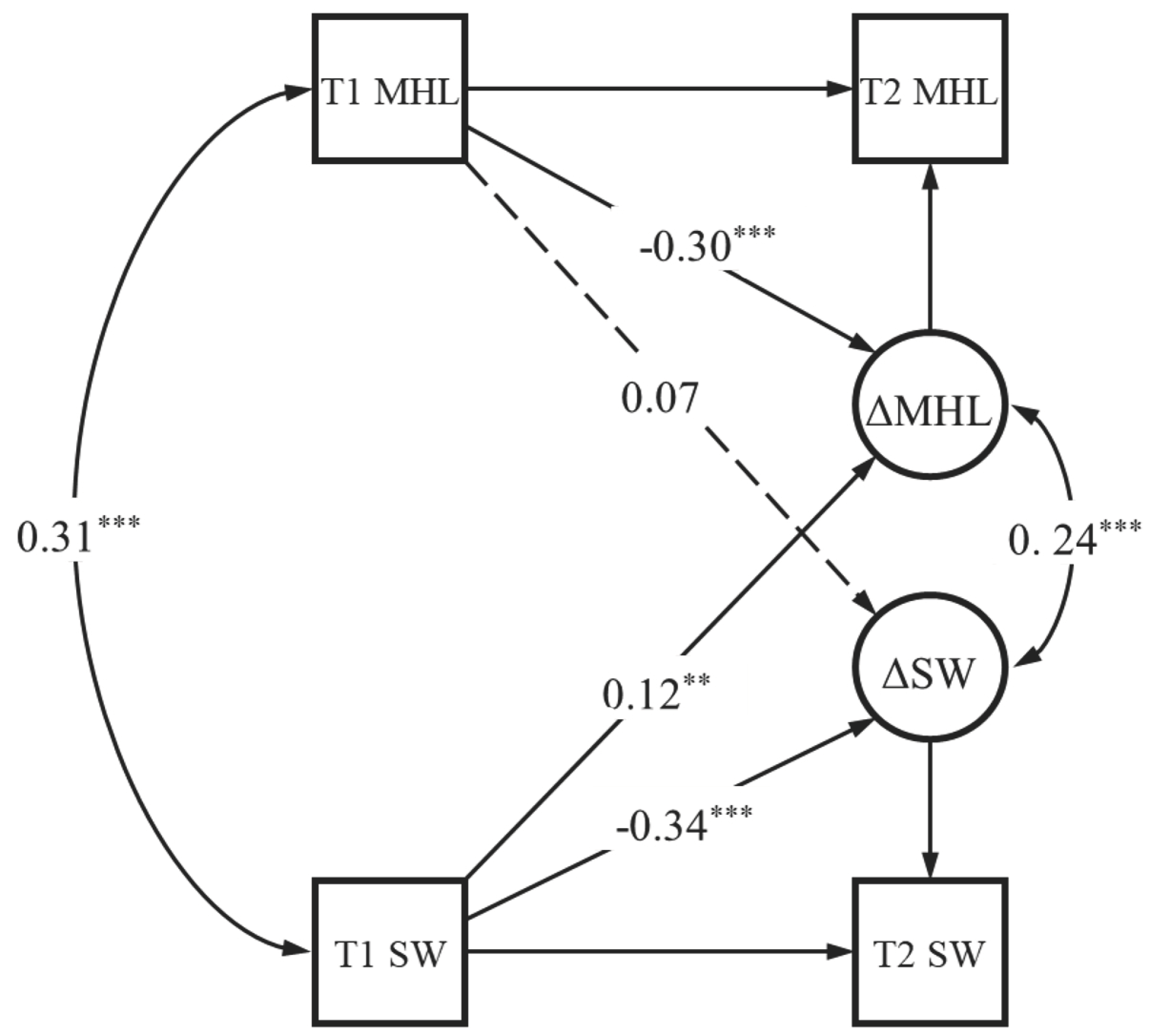

3.4. Latent Change Score Model Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baldwin, C., Vincent, P., Anderson, J., & Rawstorne, P. (2020). Measuring well-being: Trial of the neighbourhood thriving scale for social well-being among pro-social individuals. International Journal of Community Well-Being, 3(3), 361–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BinDhim, N. F., Althumiri, N. A., Ad-Dab’bagh, Y., Alqahtani, M. M. J., Alshayea, A. K., Al-Luhaidan, S. M., Svendrovski, A., Al-Duraihem, R. A., & Alhabeeb, A. A. (2023). Validation and psychometric testing of the Arabic version of the mental health literacy scale among the Saudi Arabian general population. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 17(1), 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjornsen, H. N., Eilertsen, M.-E. B., Ringdal, R., Espnes, G. A., & Moksnes, U. K. (2017). Positive mental health literacy: Development and validation of a measure among Norwegian adolescents. BMC Public Health, 17, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjornsen, H. N., Espnes, G. A., Eilertsen, M.-E. B., Ringdal, R., & Moksnes, U. K. (2019). The relationship between positive mental health literacy and mental well-being among adolescents: Implications for school health services. Journal of School Nursing, 35(2), 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brijnath, B., Protheroe, J., Mahtani, K. R., & Antoniades, J. (2016). Do web-based mental health literacy interventions improve the mental health literacy of adult consumers? Results from a systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(6), e165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design (Vol. 2). Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burgard, S. S. C., Liber, J. M., Geurts, S. M., & Koning, I. M. (2022). Youth sensitivity in a pandemic: The relationship between sensory processing sensitivity, internalizing problems, COVID-19 and parenting. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 31(6), 1501–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, D., Sequeira, C., Querido, A., Tomas, C., Morgado, T., Valentim, O., Moutinho, L., Gomes, J., & Laranjeira, C. (2022). Positive mental health literacy: A concept analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 877611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.-B., & Zhou, N. (2019). The weight status of only children in China: The role of marital satisfaction and maternal warmth. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(10), 2754–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicognani, E., Pirini, C., Keyes, C., Joshanloo, M., Rostami, R., & Nosratabadi, M. (2008). Social participation, sense of community and social well being: A study on American, Italian and Iranian University students. Social Indicators Research, 89(1), 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, M. E., Ravid, A., Gibb, B., George-Denn, D., Bronstein, L. R., & McLeod, S. (2016). Adolescent mental health literacy: Young people’s knowledge of depression and social anxiety disorder. Journal of Adolescent Health, 58(1), 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, M. M., da Luz Vale-Dias, M., Keyes, C., & Carvalho, S. A. (2022). The positive mental health literacy questionnaire-PosMHLit. Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology, 10(2), 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. (2009). The science of well-being. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Dosari, M., Aldayel, S. K., Alduraibi, K. M., Alturki, A. A., Aljehaiman, F., Alamri, S., Alshammari, H. S., & Alsuwailem, M. (2023). Prevalence of highly sensitive personality and its relationship with depression, and anxiety in the Saudi general population. Cureus Journal of Medical Science, 15(12), e49834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferschmann, L., Grydeland, H., MacSweeney, N., Beck, D., Bos, M. G. N., Norbom, L. B., Eira Aksnes, R., Bekkhus, M., Havdahl, A., Crone, E. A., von Soest, T., & Tamnes, C. K. (2024). The importance of timing of socioeconomic disadvantage throughout development for depressive symptoms and brain structure. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 69, 101449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furnham, A., Annis, J., & Cleridou, K. (2014). Gender differences in the mental health literacy of young people. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 26(2), 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, A., & Violato, C. (2010). The development and psychometric assessment of an instrument to measure attitudes towards depression and its treatments in patients suffering from non-psychotic depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 124(3), 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, M. W., Lopez, S. J., & Preacher, K. J. (2009). The hierarchical structure of well-being. Journal of Personality, 77(4), 1025–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorczynski, P., Sims-Schouten, W., & Wilson, C. (2020). Evaluating mental health literacy and help-seeking behaviours in UK university students: A country wide study. Journal of Public Mental Health, 19(4), 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzah, S. R. a., Musa, S. N. S., Badruldin, M. N. W. B., Amiludin, N. A., Zameram, Q. A., Kamaruzaman, M. J. M., Said, N. N., & Haniff, N. A. A. (2023). Identifying predictors of university students? Mental well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Kontakt-Journal of Nursing and Social Sciences Related to Health and Illness, 25(1), 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzinger, A., Floris, F., Schomerus, G., Carta, M. G., & Angermeyer, M. C. (2012). Gender differences in public beliefs and attitudes about mental disorder in western countries: A systematic review of population studies. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 21(1), 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacka, F. N., O’Neil, A., Opie, R., Itsiopoulos, C., Cotton, S., Mohebbi, M., Castle, D., Dash, S., Mihalopoulos, C., Chatterton, M. L., Brazionis, L., Dean, O. M., Hodge, A. M., & Berk, M. (2017). A randomised controlled trial of dietary improvement for adults with major depression (the ‘SMILES’ trial). BMC Medicine, 15, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafari, A., Nejatian, M., Momeniyan, V., Barsalani, F. R., & Tehrani, H. (2021). Mental health literacy and quality of life in Iran: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry, 21(1), 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, G., Li, D., Ren, Z., Yan, Y., Wu, X., Zhu, X., Yu, L., Xia, M., Li, F., Wei, H., Zhang, Y., Zhao, C., & Zhang, L. (2021). The status quo and characteristics of Chinese mental health literacy. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 53(2), 182–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G., Zhao, C., Wei, H., Yu, L., Li, D., Lin, X., & Ren, Z. (2020). Mental health literacy: Connotation, measurement and new framework. Journal of Psychological Science, 43, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorm, A. F. (2000). Mental health literacy: Public knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 177(5), 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorm, A. F. (2012). Mental health literacy: Empowering the community to take action for better mental health. American Psychologist, 67(3), 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorm, A. F. (2015). Why we need the concept of “mental health literacy”. Health Communication, 30(12), 1166–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorm, A. F., Korten, A. E., Jacomb, P. A., Christensen, H., Rodgers, B., & Pollitt, P. (1997). “Mental health literacy”: A survey of the public’s ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Medical Journal of Australia, 166(4), 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D., Diener, E., & Schwarz, N. (1999). Well-being: Foundations of hedonic psychology. Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Kajawu, L., Chingarande, S. D., Jack, H., Ward, C., & Taylor, T. (2016). What do African traditional medical practitioners do in the treatment of mental disorders in Zimbabwe? International Journal of Culture and Mental Health, 9(1), 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C. L. M. (1998). Social well-being. Social Psychology Quarterly, 61(2), 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C. L. M. (2003). Complete mental health: An agenda for the 21st century. In Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well-lived. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes, C. L. M. (2005). Mental illness and/or mental health? Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(3), 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyes, C. L. M. (2007). Promoting and protecting mental health as flourishing: A complementary strategy for improving national mental health. American Psychologist, 62(2), 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C. L. M., & Shapiro, A. D. (2003). Social well-being in the United States: A descriptive epidemiology. In O. G. Brim, C. D. Ryff, & R. C. Kessler (Eds.), How healthy are we? (pp. 350–372) University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kievit, R. A., Brandmaier, A. M., Ziegler, G., van Harmelen, A.-L., de Mooij, S. M. M., Moutoussis, M., Goodyer, I. M., Bullmore, E., Jones, P. B., Fonagy, P., Consortium, N. S. P. N., Lindenberger, U., & Dolan, R. J. (2018). Developmental cognitive neuroscience using latent change score models: A tutorial and applications. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 33, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhnert, R.-L., Begeer, S., Fink, E., & de Rosnay, M. (2017). Gender-differentiated effects of theory of mind, emotion understanding, and social preference on prosocial behavior development: A longitudinal study. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 154, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutcher, S., Bagnell, A., & Wei, Y. (2015). Mental health literacy in secondary schools: A Canadian approach. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 24(2), 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutcher, S., Wei, Y., & Coniglio, C. (2016). Mental health literacy: Past, present, and future. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry-Revue Canadienne De Psychiatrie, 61(3), 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, J. S. (1993). The measurement of social well-being. Social Indicators Research, 28(3), 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., & Jiang, Q. (2021). Who benefits from being an only child? A study of parent-child relationship among Chinese junior high school students. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 608995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lluch-Canut, T., Puig-Llobet, M., Sanchez-Ortega, A., Roldan-Merino, J., Ferre-Grau, C., & Positive Mental Hlth Res, G. (2013). Assessing positive mental health in people with chronic physical health problems: Correlations with socio-demographic variables and physical health status. BMC Public Health, 13, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoodi, S. M. H., Rasoulian, M., Khodadoust, E., Jabari, Z., Emami, S., & Ahmadzad-Asl, M. (2023). The well-being of Iranian adult citizens; is it related to mental health literacy? Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1127639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malone, C., & Wachholtz, A. (2018). The relationship of anxiety and depression to subjective well-being in a mainland Chinese sample. Journal of Religion & Health, 57(1), 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markram, K., & Markram, H. (2010). The intense world theory: A unifying theory of the neurobiology of autism. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 4, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y., & Wang, Q. (2009). An empirical study on social well-being. Journal of Gannan Normal University, 30(4), 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y., & Zhao, S. (2009). From social well-being to positive mental health model: Keyes’s introduction and assessment. Psychological Research, 2(5), 13–16+25. [Google Scholar]

- Ming, Z. J., & Chen, Z. Y. (2020). Mental health literacy: Concept, measurement, intervention and effect. Advances in Psychological Science, 28(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Torres, R., Carrasco-Gubernatis, C., Grasso-Cladera, A., Cosmelli, D., Parada, F. J., & Palacios-Garcia, I. (2023). Psychobiotic effects on anxiety are modulated by lifestyle behaviors: A randomized placebo-controlled trial on healthy adults. Nutrients, 15(7), 1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moser, G. (2009). Quality of life and sustainability: Toward person–environment congruity. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 29(3), 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalipay, M. J. N., Chai, C.-S., Jong, M. S.-Y., King, R. B., & Mordeno, I. G. (2024). Positive mental health literacy for teachers: Adaptation and construct validation. Current Psychology, 43(6), 4888–4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, M., & Casey, L. (2015). The mental health literacy scale (MHLS): A new scale-based measure of mental health literacy. Psychiatry Research, 229(1–2), 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M. E., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction (Vol. 55). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Son, J., & Wilson, J. (2012). Volunteer work and hedonic, eudemonic, and social well-being. Sociological Forum, 27(3), 658–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiker, D. A., & Hammer, J. H. (2019). Mental health literacy as theory: Current challenges and future directions. Journal of Mental Health, 28(3), 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambling, R. R., D’Aniello, C., & Russell, B. S. (2023). Mental health literacy: A critical target for narrowing racial disparities in behavioral health. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 21(3), 1867–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Z., Yang, X., Tan, W., Ke, Y., Kou, C., Zhang, M., Liu, L., Zhang, Y., Li, X., Li, W., & Wang, S. B. (2024). Patterns of unhealthy lifestyle and their associations with depressive and anxiety symptoms among Chinese young adults: A latent class analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 352, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, J. L., Tay, Y. F., & Klainin-Yobas, P. (2018). Mental health literacy levels. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 32(5), 757–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J., He, Y., Jiang, Q., Cai, J., Wang, W., Zeng, Q., Miao, J., Qi, X., Chen, J., Bian, Q., Cai, C., Ma, N., Zhu, Z., & Zhang, M. (2013). Mental health literacy among residents in Shanghai. Shanghai Archives of Psychiatry, 25(4), 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterman, A. S. (1993). Two conceptions of happiness: Contrasts of personal expressiveness (eudaimonia) and hedonic enjoyment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(4), 678–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y., McGrath, P. J., Hayden, J., & Kutcher, S. (2015). Mental health literacy measures evaluating knowledge, attitudes and help-seeking: A scoping review. BMC Psychiatry, 15, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winding, T. N., Nielsen, M. L., & Grytnes, R. (2023). Perceived stress in adolescence and labour market participation in young adulthood-a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J., Wang, C., Lu, Y., Zhu, X., Li, Y., Liu, G., & Jiang, G. (2023). Development and initial validation of the mental health literacy questionnaire for Chinese adults. Current Psychology, 42(10), 8425–8440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y., Zhang, L., Zhao, J., & Kong, F. (2023). The relationship between gratitude and social well-being: Evidence from a longitudinal study and a daily diary investigation. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 55(7), 1087–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, F., John, W. C. M., Qiao, D., & Sun, X. (2023). Association between psychological distress and mental help-seeking intentions in international students of national university of Singapore: A mediation analysis of mental health literacy. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., Chen, S., Wang, X., Liu, J., Zhang, Y., Mei, Y., & Zhang, Z. (2023). The relationship between mental health literacy and subjective well-being of young and middle-aged residents: Perceived the mediating role of social support and its urban-rural differences. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 25(4), 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.-L., Wang, S.-B., Ding, K.-R., Tan, W.-Y., & Zhou, L. (2024). Low mental health literacy is associated with depression and anxiety among adults: A population-based survey of 16,715 adults in China. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M ± SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. T1 MHL | 39.11 ± 8.10 | - | ||||||

| 2. T1 SW | 51.61 ± 10.02 | 0.31 ** | - | |||||

| 3. T2 MHL | 40.60 ± 10.15 | 0.58 ** | 0.27 ** | - | ||||

| 4. T2 SW | 54.61 ± 11.25 | 0.25 ** | 0.64 ** | 0.35 ** | - | |||

| 5. Gender | - | −0.17 ** | 0.02 | −0.23 ** | −0.01 | - | ||

| 6. SC | - | 0.08 * | −0.04 | 0.08 * | 0.02 | 0.002 | - | |

| 7. SES | - | 0.08 * | 0.01 | 0.08 * | 0.06 | −0.06 | 0.43 ** | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pan, J.; Xu, T.; Li, D. The Relationship Between Mental Health Literacy and Social Well-Being: A Longitudinal Study in China. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15010029

Pan J, Xu T, Li D. The Relationship Between Mental Health Literacy and Social Well-Being: A Longitudinal Study in China. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(1):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15010029

Chicago/Turabian StylePan, Jiali, Tianyu Xu, and Dan Li. 2025. "The Relationship Between Mental Health Literacy and Social Well-Being: A Longitudinal Study in China" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 1: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15010029

APA StylePan, J., Xu, T., & Li, D. (2025). The Relationship Between Mental Health Literacy and Social Well-Being: A Longitudinal Study in China. Behavioral Sciences, 15(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15010029