Relationship between Family Variables and Career Adaptability: A Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Career Adaptability

1.2. Family Variables

1.2.1. Family Support

1.2.2. Parental Career-Related Behaviors

1.2.3. Family Socioeconomic Status

1.3. Moderators in the Relationship between Family Variables and CA

1.4. The Present Study

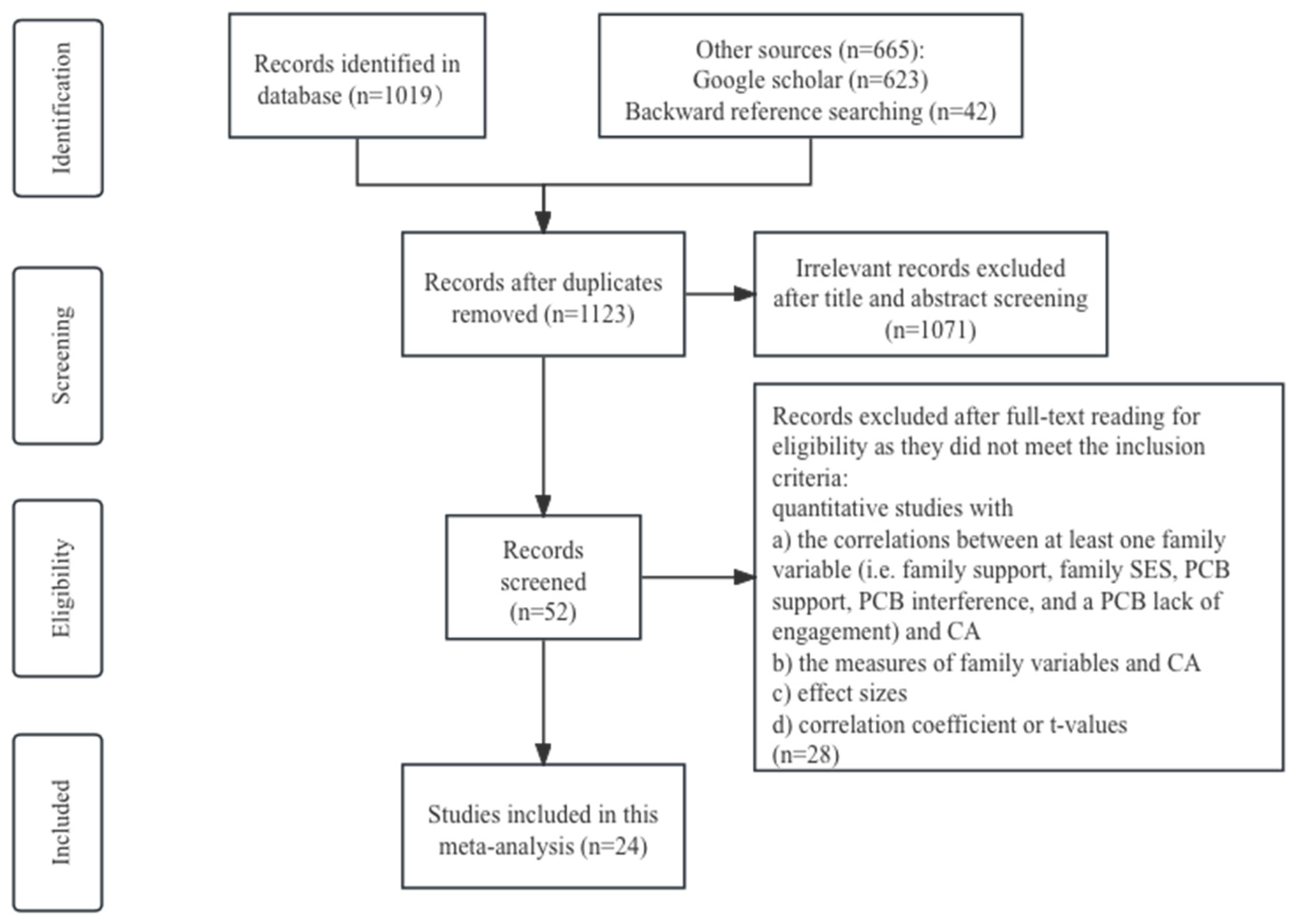

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction and Coding

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

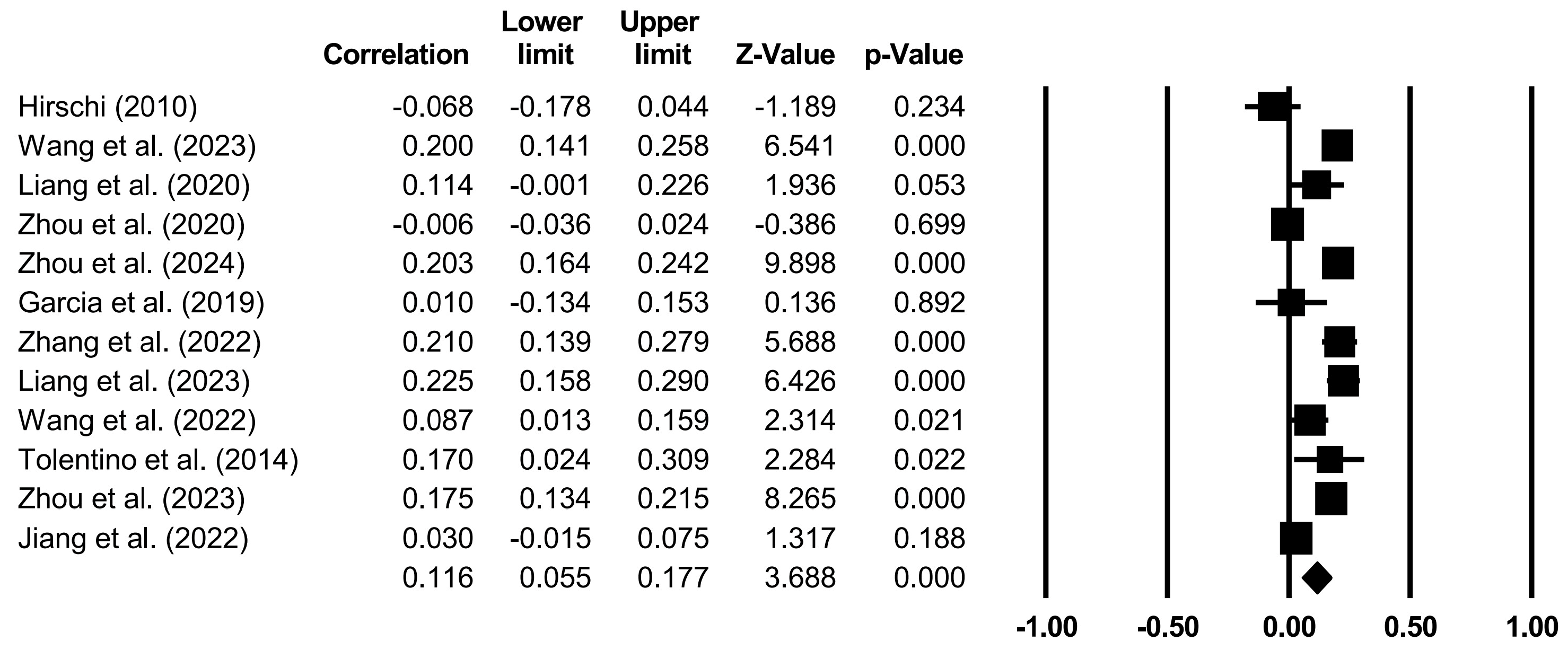

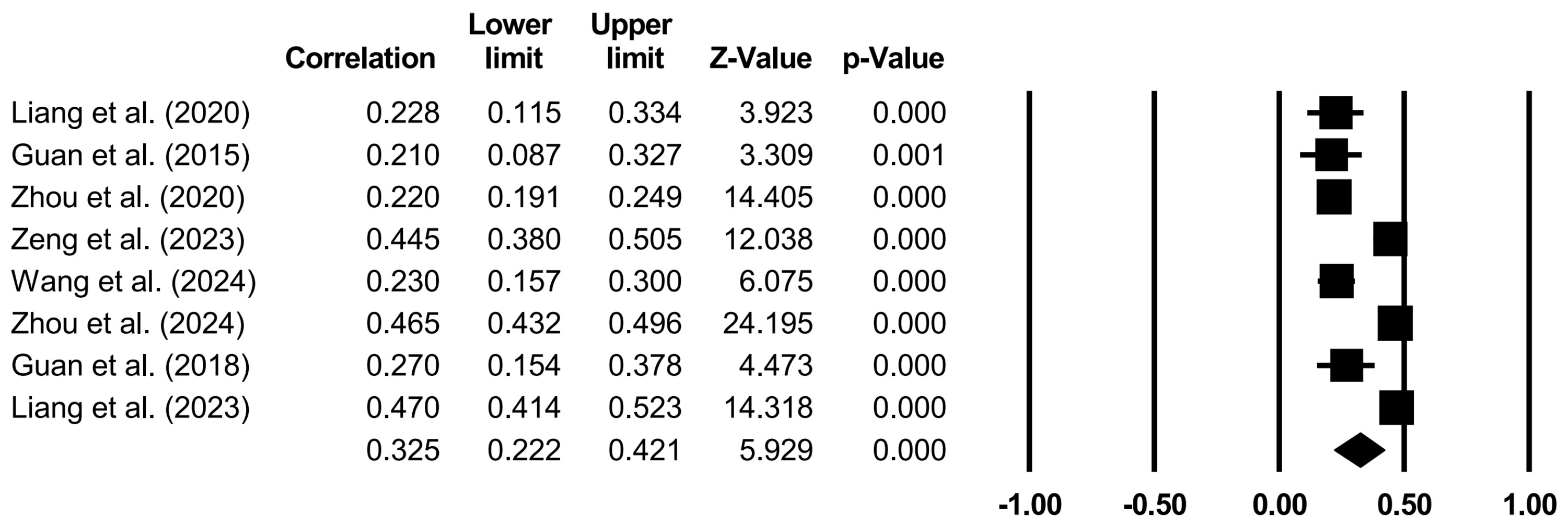

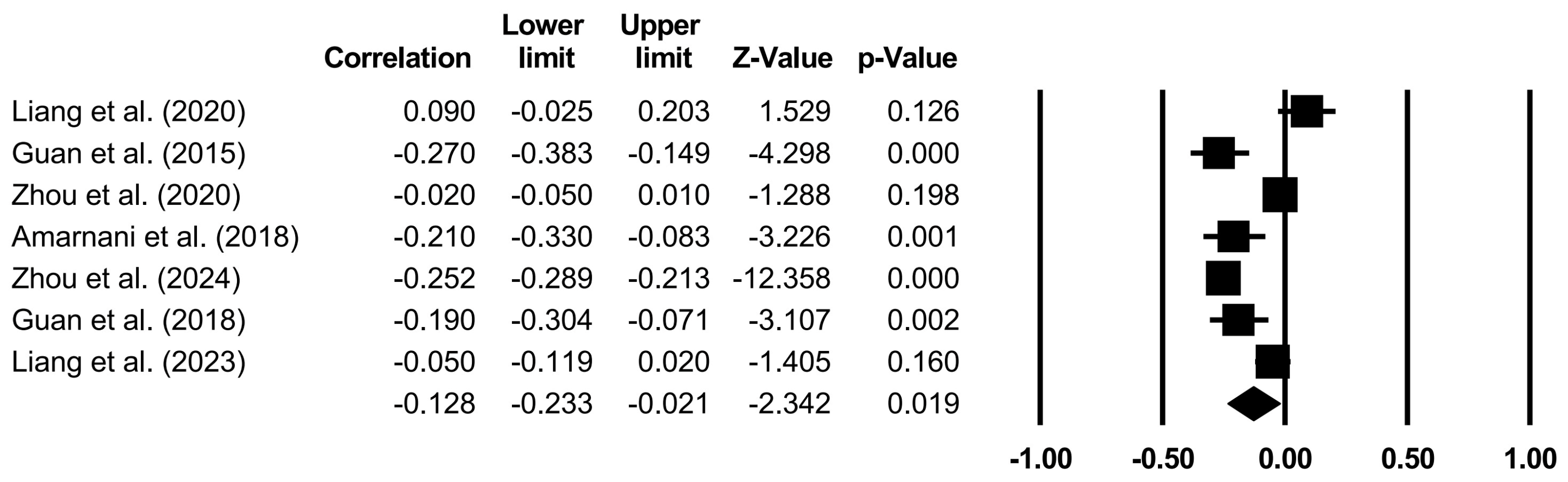

3.1. Effect Size and the Homogeneity Test

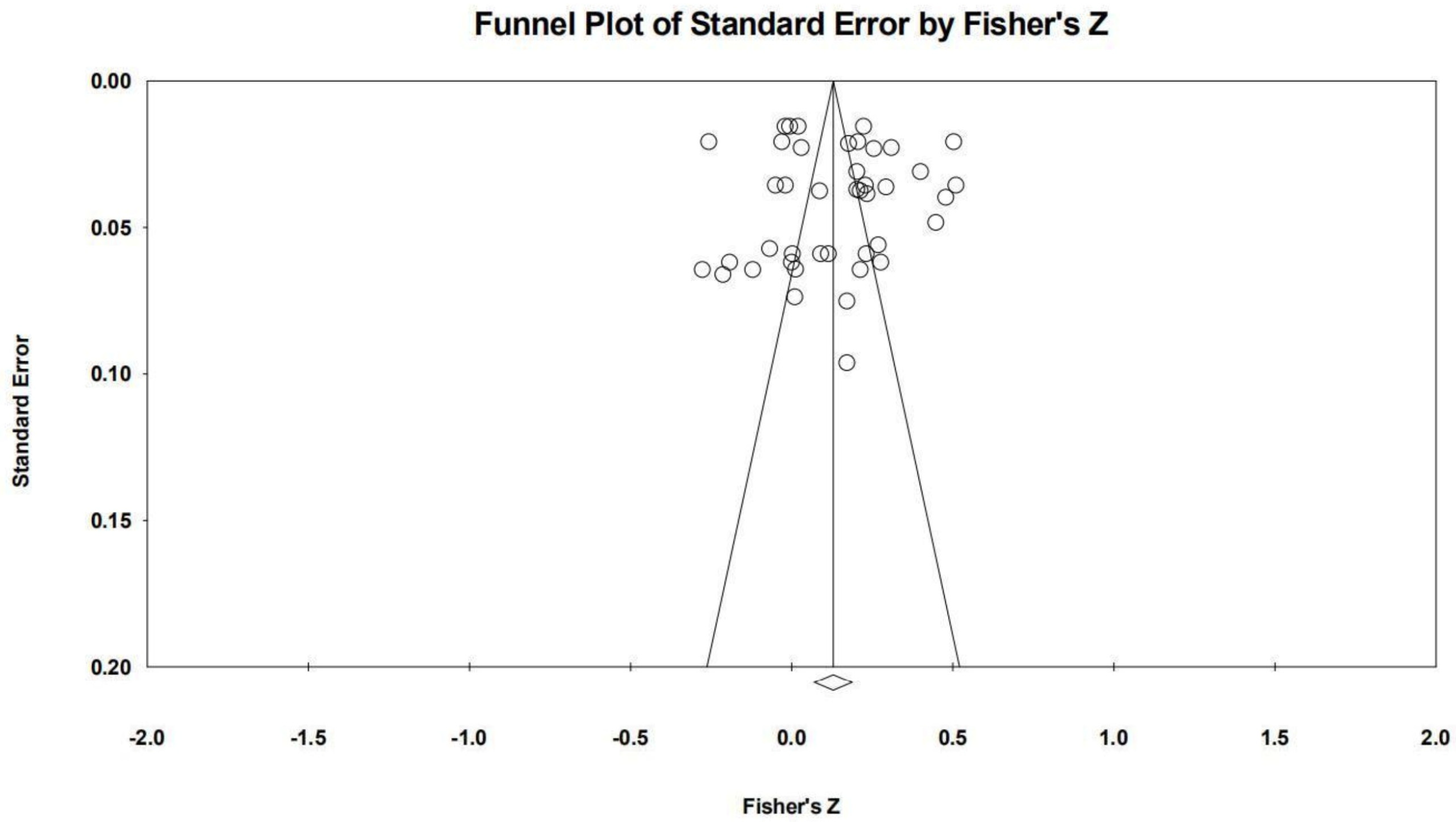

3.2. Publication Bias

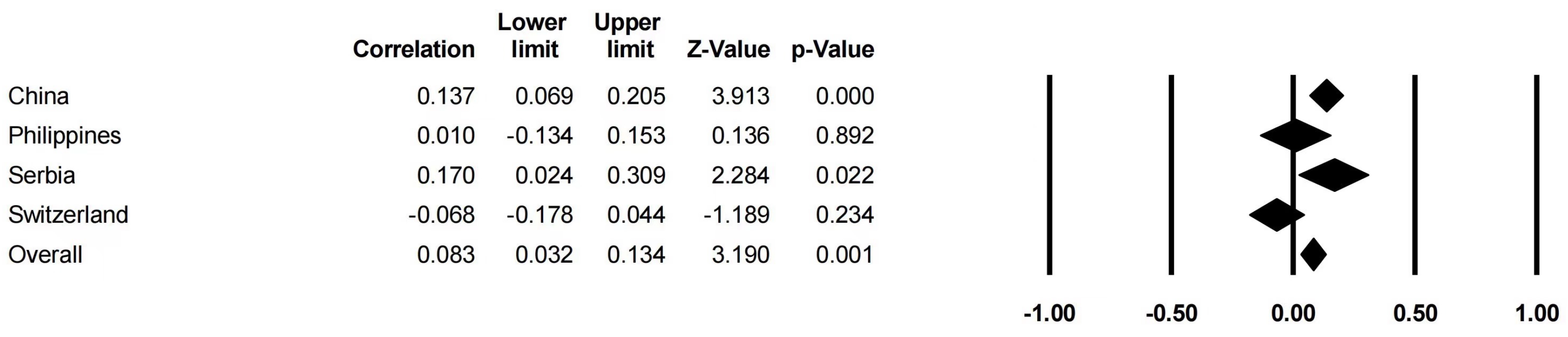

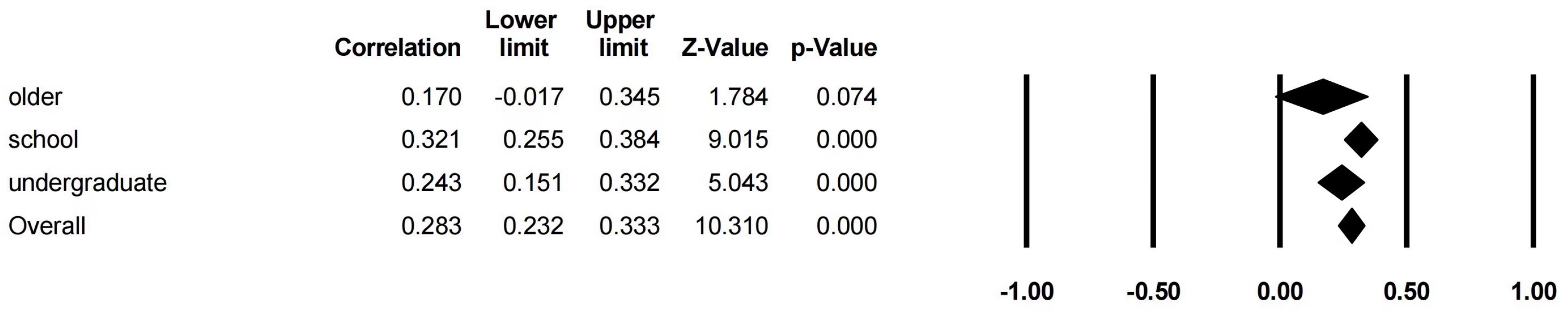

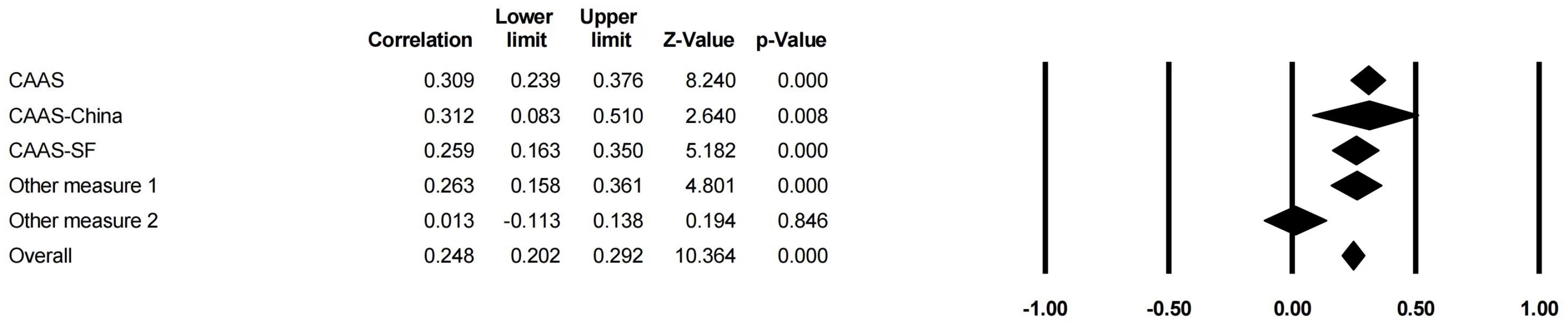

3.3. Moderator Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. The Relationship between Family Variables and Career Adaptability

4.1.1. Family Support and PCB Support

4.1.2. Family SES

4.1.3. A PCB Lack of Engagement

4.1.4. PCB Interference

4.2. The Moderators in the Relationship between Family Variables and Career Adaptability

4.3. Implications

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Super, D.E. A Life-Span, Life-Space approach to career development. J. Vocat. Behav. 1980, 16, 282–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanberg, C.R.; Csillag, B.; Douglass, R.P.; Zhou, L.; Pollard, M.S. Socioeconomic status and well-being during COVID-19: A resource-based examination. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M.L. The theory and practice of career construction. In Career Development and Counseling: Putting Theory and Research to Work; Brown, D., Lent, R.W., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 42–70. [Google Scholar]

- Koen, J.; Klehe, U.C.; Van Vianen, A.E. Training career adaptability to facilitate a successful school-to-work transition. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 81, 395–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD Employment Outlook 2020: Worker Security and the COVID-19 Crisis; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D.; Hackett, G. Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. J. Vocat. Behav. 1994, 45, 79–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langford, C.P.H.; Bowsher, J.; Maloney, J.P.; Lillis, P.P. Social support: A conceptual analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 1997, 25, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryant, B.K.; Zvonkovic, A.M.; Reynolds, P. Parenting in relation to child and adolescent vocational development. J. Vocat. Behav. 2006, 69, 149–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M.L. Career adaptability: An integrative construct for Life-Span, Life-Space theory. Career Dev. Q. 1997, 45, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M.L.; Porfeli, E.J. Career Adapt-Abilities Scale: Construction, reliability, and measurement equivalence across 13 countries. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.J.; Leung, S.A.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Xu, H. Career adapt-abilities scale—China form: Construction and initial validation. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 686–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggiori, C.; Rossier, J.; Savickas, M.L. Career adapt-abilities scale–short form (CAAS-SF): Construction and validation. J. Career Assess. 2017, 25, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, C.S. A systematic review of the career adaptability literature and future outlook. J. Career Assess. 2016, 26, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, A. Swiss adolescents’ career aspirations: Influence of context, age, and career adaptability. J. Career Dev. 2010, 36, 228–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udayar, S.; Fiori, M.; Thalmayer, A.G.; Rossier, J. Investigating the link between trait emotional intelligence, career indecision, and self-perceived employability: The role of career adaptability. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2018, 135, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Fan, W.; Zhang, L.F. Career adaptability and career choice satisfaction: Roles of career self-efficacy and socioeconomic status. Career Dev. Q. 2023, 71, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haenggli, M.; Hirschi, A. Career adaptability and career success in the context of a broader career resources framework. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 119, 103414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiston, S.C.; Keller, B.K. The influences of the family of origin on career development: A review and analysis. Couns. Psychol. 2004, 32, 493–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, P.R.J.M.; Restubog, S.L.D.; Bordia, P.; Bordia, S.; Roxas, R.E.O. Career optimism: The roles of contextual support and career decision-making self-efficacy. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 88, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Zhou, N.; Dou, K.; Cao, H.; Li, J.-B.; Wu, Q.; Liang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Nie, Y. Career-related parental behaviors, adolescents’ consideration of future consequences, and career adaptability: A three-wave longitudinal study. J. Couns. Psychol. 2020, 67, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Meng, H.; Wang, S.; Liang, Y.; Nie, R.; Jiang, L.; Li, B.; Cao, H.; Zhou, N. Adolescents’ family socioeconomic status, teacher-student interactions, and career ambivalence/adaptability: A three-wave longitudinal study. J. Career Dev. 2023, 50, 445–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Hlad′o, P.; Kvasková, L.; Ježek, S.; Hirschi, A.; Macek, P. Career adaptability and social support of vocational students leaving upper secondary school. J. Career Assess. 2020, 28, 478–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Mu, F.; Zhang, J.; Fu, M. The relationships between career-related emotional support from parents and teachers and career adaptability. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 823333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kvitkovičová, L.; Umemura, T.; Macek, P. Roles of attachment relationships in emerging adults’ career decision-making process: A two-year longitudinal research design. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 101, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Miao, H.; Guo, C. Career decision self-efficacy mediates social support and career adaptability and stage differences. J. Career Assess. 2024, 32, 264–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulenberg, J.E.; Vondracek, F.W.; Crouter, A.C. The influence of the family on vocational development. J. Marriage Fam. 1984, 46, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, J.; Kracke, B. Career-specific parental behaviors in adolescents’ development. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009, 75, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Pschol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, R.K. Beyond parental control and authoritarian parenting style: Understanding Chinese parenting through the cultural notion of training. Child Dev. 1994, 65, 1111–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.D.; Christopher-Sisk, E.K.; Gravino, K.L. Making career decisions in a relational context. Couns. Psychol. 2001, 29, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.D.; Blustein, D.L.; Jobin-Davis, K.; White, S.F. Preparation for the school-to-work transition: The views of high school students. J. Vocat. Behav. 2002, 61, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Benner, A.D. Parent–child discrepancies in educational expectations: Differential effects of actual versus perceived discrepancies. Child Dev. 2014, 85, 891–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, R.K. The parenting of immigrant Chinese and European American mothers: Relations between parenting styles, socialization goals, and parental practices. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2000, 21, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, B.K. Parental psychological control: Revisiting a neglected construct. Child Dev. 1996, 67, 3296–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, N.; Cao, H.; Nie, Y.; Li, X.; Yu, S.; Liang, Y.; Deng, L.; Buehler, N.; Zang, N.; Sun, R.; et al. Career-related parental processes and career adaptability and ambivalence among Chinese adolescents: A person-centered approach. J. Res. Adolesc. 2020, 30, 234–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley-Geist, J.C.; Olson-Buchanan, J.B. Helicopter parents: An examination of the correlates of over-parenting of college students. Educ. Train. 2014, 56, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortimer, J.T.; Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J.; Holmes, M.; Shanahan, M.J. The process of occupational decision making: Patterns during the transition to adulthood. J. Vocat. Behav. 2002, 61, 439–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignoli, E.; Croity-Belz, S.; Chapeland, V.; de Fillipis, A.; Garcia, M. Career exploration in adolescents: The role of anxiety, attachment, and parenting style. J. Vocat. Behav. 2005, 67, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lim, V.K.G.; Teo, T.S.H. The long arm of job insecurity: Its impact on career-specific parenting behaviors and youths’ career self-efficacy. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Cao, H.; Wang, S.; Li, X.; Liang, Y. Parental career expectation predicts adolescent career development through career-related parenting practice: Transactional dynamics across high school years. J. Career Assess. 2024, 32, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Wang, F.; Liu, H.; Ji, Y.; Jia, X.; Fang, Z.; Li, Y.; Hua, H.; Li, C. Career-specific parental behaviors, career exploration and career adaptability: A three-wave investigation among Chinese undergraduates. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 86, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D. Social cognitive model of career self-management: Toward a unifying view of adaptive career behavior across the life span. J. Couns. Psychol. 2013, 60, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Barbaranelli, C.; Caprara, G.V.; Pastorelli, C. Self-efficacy beliefs as shapers of children’s aspirations and career trajectories. Child Dev. 2001, 72, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohn, M.L.; Slomczynski, K.M. Social Structure and Self-Direction: A Comparative Analysis of the United States and Poland; Blackwell Publishers: Warsaw, Poland, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Li, Q.; Zhou, T.; Li, C.; Gu, C.; Zhao, X. Social creativity and entrepreneurial intentions of college students: Mediated by career adaptability and moderated by parental entrepreneurial background. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 893351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, T.J.; Qian, S.; Miao, C.; Fiet, J.O. The relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions: A meta-analytic review. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 217–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoon, I.; Parsons, S. Teenage aspirations for future careers and occupational outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2002, 60, 262–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Lin, X.; Wang, L. The paradoxical effects of social class on career adaptability: The role of intolerance of uncertainty. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1064603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenny, M.E.; Bledsoe, M. Contributions of the relational context to career adaptability among urban adolescents. J. Vocat. Behav. 2005, 66, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, P.; Capezio, A.; Restubog, S.L.D.; Read, S.; Lajom, J.A.L.; Li, M. The role of traditionality in the relationships among parental support, career decision-making self-efficacy and career adaptability. J. Vocat. Behav. 2016, 94, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.; Li, S.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, J. Longitudinal effect of career-related parental support on vocational college students’ proactive career behavior: A moderated mediation model. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 11422–11434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, W.A.; Laursen, B. Changing relationships, changing youth: Interpersonal contexts of adolescent development. J. Early Adolesc. 2004, 24, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, W.; Lokan, J. Perspectives on Donald Super’s construct of career maturity. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guid. 2001, 1, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yuen, M.; Chen, G. Career-related parental support, vocational identity, and career adaptability: Interrelationships and gender Differences. Career Dev. Q. 2021, 69, 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Gong, Q.; Cai, Z.; Xu, S.L.; Xiang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Chen, S.X.; Hu, H.; Tian, L. Parents’ career values, adaptability, career-specific parenting behaviors, and undergraduates’ career adaptability. Couns. Psychol. 2018, 46, 922–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creed, P.A.; Fallon, T.; Hood, M. The relationship between career adaptability, person and situation variables, and career concerns in young adults. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009, 74, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X. A research summary on career development planning education for middle school students in China. In Proceedings of the 2020 3rd International Conference on E-Business, Information Management and Computer Science, Wuhan, China, 5–6 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, C.W.; Lavigne, K.N.; Katz, I.M.; Zacher, H. Linking dimensions of career adaptability to adaptation results: A meta-analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 102, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, S.M.; Yang, L.; Lau, C.D.; Wong, C.W.V.; Su, X. Associations of parental variables and youth’s career decision-making self-efficacy: A meta-analysis. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2022, 31, 530–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Dong, W. Relationship between Family Variables and Career Adaptability: A Meta-Analysis; OSF: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Super, D.E.; Knasel, E.G. Career development in adulthood: Some theoretical problems and a possible solution. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 1981, 9, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Fan, X. Adversity quotients, environmental variables and career adaptability in student nurses. J. Vocat. Behav. 2014, 85, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarnani, R.K.; Garcia, P.R.J.M.; Restubog, S.L.D.; Bordia, P.; Bordia, S. Do you think I’m worth it? The self-verifying role of parental engagement in career adaptability and career persistence among STEM students. J. Career Assess. 2018, 26, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Li, J.; Huang, S.; Wang, J.; Huang, F.; Kang, D.; Zhang, M. How does career-related parental support enhance career adaptability: The multiple mediating roles of resilience and hope. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 25193–25205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Dunwoodie, K.; Jiang, Z.; Nielsen, I. Openness to experience and the career adaptability of refugees: How do career optimism and family social support matter? J. Career Assess. 2022, 30, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, P.R.J.M.; Restubog, S.L.D.; Ocampo, A.C.; Wang, L.; Tang, R.L. Role modeling as a socialization mechanism in the transmission of career adaptability across generations. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 111, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Zhou, N.; Cao, H. Stability and change in configuration patterns of various career-related parental behaviors and their associations with adolescent career adaptability: A longitudinal person-centered analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 2023, 145, 103916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolentino, L.R.; Sedoglavich, V.; Lu, V.N.; Garcia, P.R.J.M.; Restubog, S.L.D. The role of career adaptability in predicting entrepreneurial intentions: A moderated mediation model. J. Vocat. Behav. 2014, 85, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Meng, H.; Cao, H.; Liang, Y. Too-much-of-a-good-thing? The curvilinear associations among Chinese adolescents’ perceived parental career expectation, internalizing problems, and career development: A three-wave longitudinal study. J. Couns. Psychol. 2023, 70, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, R.; Fan, R.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y. Understanding the serial mediating effects of career adaptability and career decision-making self-efficacy between parental autonomy support and academic engagement in Chinese secondary vocational students. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 953550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, M.; Hedges, L.V.; Higgins, J.P.; Rothstein, H.R. Introduction to Meta-Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Huedo-Medina, T.B.; Sánchez-Meca, J.; Marín-Martínez, F.; Botella, J. Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I2 index? Psychol. Methods 2006, 11, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, J.L.; Sutton, A.J.; Jones, D.R.; Abrams, K.R.; Rushton, L. Comparison of two methods to detect publication bias in meta-analysis. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2006, 295, 676–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsey, M.W.; Wilson, D.B. Practical Meta-Analysis; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Studies (Year) | N | Family Variables | Region | Age Stages | Female% | CA Measure | r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [65] (2014) | 431 | Family support | China | University | 55.8 | CAAS-China | 0.42 |

| [14] (2010) | 308 | Family SES | Switzerland | School | 50 | Other measure 1 * | −0.068 |

| [23] (2020) | 1874 | Family support | The Czech Republic | University | 46.5 | CAAS | 0.25 |

| [26] (2023) | 1044 | Family support | China | School | 44.56 | CAAS | 0.38 |

| Family SES | 0.2 | ||||||

| [20] (2020) | 290 | Family SES | China | School | 46.3 | CAAS | 0.1138 |

| PCB support | 0.2275 | ||||||

| PCB interference | 0.0025 | ||||||

| PCB lack of engagement | 0.09 | ||||||

| [43] (2015) | 244 | PCB support | China | University | 60 | CAAS-China | 0.21 |

| PCB interference | −0.12 | ||||||

| PCB lack of engagement | −0.27 | ||||||

| [37] (2020) | 4151 | Family SES | China | School | 51.99 | CAAS | −0.006 |

| PCB support | 0.22 | ||||||

| PCB interference | 0.02 | ||||||

| PCB lack of engagement | −0.02 | ||||||

| [51] (2005) | 322 | Family support | America | School | 53.9 | Other measure 2 * | 0.2625 |

| [66] (2018) | 232 | PCB lack of engagement | The Philippines | University | 34 | CAAS | −0.21 |

| [67] (2023) | 636 | PCB support | China | School | 48.7 | CAAS | 0.445 |

| [53] (2024) | 676 | PCB support | China | University | 53.84 | CAAS-SF | 0.23 |

| [68] (2022) | 111 | Family support | Australia | Older (37.76) | 33.04 | CAAS-SF | 0.17 |

| [42] (2024) | 2315 | Family SES | China | School | 52.8 | CAAS | 0.203 |

| PCB support | 0.464625 | ||||||

| PCB interference | −0.03025 | ||||||

| PCB lack of engagement | −0.2515 | ||||||

| [57] (2018) | 264 | PCB support | China | University | 70.5 | CAAS-China | 0.27 |

| PCB interference | 0 | ||||||

| PCB lack of engagement | −0.19 | ||||||

| [69] (2019) | 187 | Family SES | The Philippines | University | 44.9 | CAAS-SF | 0.01 |

| [47] (2022) | 715 | Family SES | China | University | 52 | CAAS-China | 0.21 |

| [70] (2023) | 791 | Family SES | China | School | 52.4 | CAAS | 0.225 |

| PCB support | 0.47 | ||||||

| PCB interference | −0.0192 | ||||||

| PCB lack of engagement | −0.05 | ||||||

| [59] (2022) | 712 | Family SES | China | University | 63.2 | CAAS-China | 0.0867 |

| [58] (2009) | 245 | Family support | Australia | University | 83.7 | Other measure 3 * | 0.0125 |

| [24] (2022) | 765 | Family support | China | University | 0 | CAAS-SF | 0.285 |

| [71] (2014) | 180 | Family SES | Serbia | University | 44 | CAAS | 0.17 |

| [52] (2016) | 731 | Family support | China | University | 36.1 | CAAS-China | 0.2 |

| [72] (2023) | 2188 | Family SES | China | School | 52.8 | CAAS | 0.175 |

| [73] (2022) | 1930 | Family support | China | School | 34.2 | CAAS | 0.3 |

| Family SES | 0.03 |

| k | N | r | 95%CI | Heterogeneity | Tau-Squared | Test of Null | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q | p | I2 | Tau2 | SE | Tau | Z | ||||

| 42 | 47,973 | 0.128 | [0.070, 0.196] | 1669.143 | 0.000 | 97.544 | 0.036 | 0.012 | 0.189 | 4.290 *** |

| Family Variables | k | N | Heterogeneity | Tau-Squared | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q | p | I2 | Tau2 | SE | Tau | |||

| Family support | 9 | 7453 | 42.090 | 0.000 | 80.993 | 0.006 | 0.004 | 0.075 |

| Family SES | 12 | 14,811 | 138.948 | 0.000 | 92.083 | 0.010 | 0.006 | 0.101 |

| PCB support | 8 | 9367 | 168.356 | 0.000 | 95.842 | 0.024 | 0.018 | 0.155 |

| PCB interference | 6 | 8055 | 7.458 | 0.189 | 32.954 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.022 |

| PCB lack of engagement | 7 | 8287 | 108.487 | 0.000 | 94.469 | 0.019 | 0.017 | 0.137 |

| Family Variables | k | N | r | 95%CI | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family support | 9 | 7453 | 0.267 | [0.208, 0.325] | 8.511 *** |

| Family SES | 12 | 14,811 | 0.116 | [0.055, 0.177] | 3.688 *** |

| PCB support | 8 | 9367 | 0.325 | [0.222, 0.421] | 5.929 *** |

| PCB interference | 6 | 8055 | −0.011 | [−0.043, 0.021] | −0.682 |

| PCB lack of engagement | 7 | 8287 | −0.128 | [−0.233, −0.021] | −2.342 * |

| Classic Fail-Safe N | Egger’s Intercept | SE | Lower Limit | Upper Limit | p-Value (1-Tailed) | p-Value (2-Tailed) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7168 | 1.14020 | 2.10750 | −3.11922 | 5.39961 | 0.29575 | 0.59149 |

| Family Variables | Family Support | Family SES | PCB Lack of Engagement | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qb (df) | r [LL, UL] | Qb (df) | r [LL, UL] | Qb (df) | r [LL, UL] | |

| Region | 8.958 (3) * | 11.784 (3) ** | 1.170 (1) | |||

| China | 0.317 [0.250, 0.380] | 0.137 [0.069, 0.205] | −0.116 [−0.230, 0.001] | |||

| The Philippines | n/a | 0.010 [−0.134, 0.153] | −0.210 [−0.330, −0.083] | |||

| Australia | 0.076 [−0.077, 0.225] | n/a | n/a | |||

| Switzerland | n/a | 0.170 [0.024, 0.309] | n/a | |||

| The Czech Republic | 0.25 [0.207, 0.292] | n/a | n/a | |||

| Serbia | n/a | 0.170 [0.024, 0.309] | n/a | |||

| America | 0.263 [0.158, 0.361] | n/a | n/a | |||

| Family Variables | Family Support | Family SES | PCB Support | PCB Lack of Engagement | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qb (df) | r [LL, UL] | Qb (df) | r [LL, UL] | Qb (df) | r [LL, UL] | Qb (df) | r [LL, UL] | |

| Age stage | 3.572 (2) * | 0.434 (1) | 3.348 (1) | 3.844 (1) | ||||

| School | 0.321 [0.255, 0.384] | 0.047 [−0.186, 0.274] | 0.372 [0.235, 0.495] | −0.064 [−0.207, 0.081] | ||||

| Undergraduate | 0.243 [0.151, 0.332] | 0.128 [0.062, 0.193] | 0.235 [0.180, 0.288] | −0.223 [−0.291, −0.153] | ||||

| Older | 0.170 [−0.017, 0.345] | n/a | n/a | n/a | ||||

| Family Variables | Family Support | Family SES | PCB Support | PCB Lack of Engagement | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qb (df) | r [LL, UL] | Qb (df) | r [LL, UL] | Qb (df) | r [LL, UL] | Qb (df) | r [LL, UL] | |

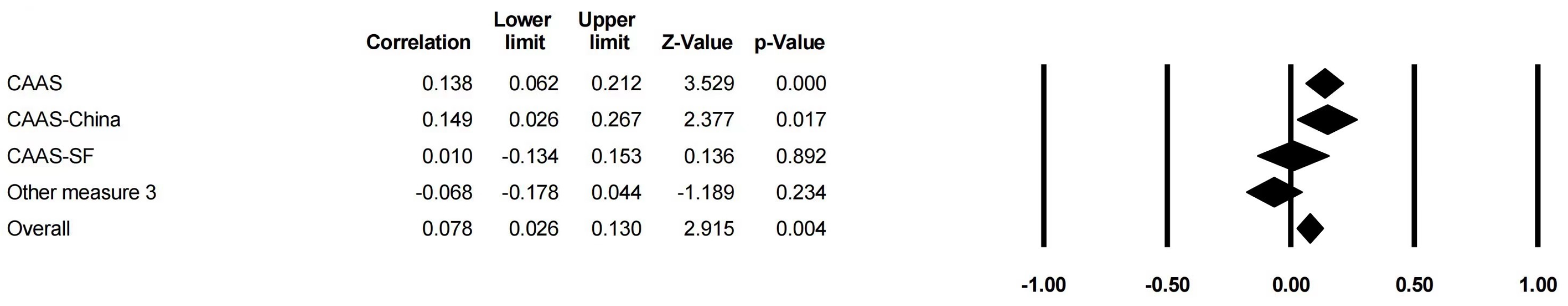

| CA Measure | 17.387 (4) ** | 11.042 (3) * | 3.390 (2) | 3.182 (1) | ||||

| CAAS | 0.309 [0.239, 0.376] | 0.138 [0.062, 0.212] | 0.372 [0.235, 0.495] | −0.091 [−0.217, 0.038] | ||||

| CAAS-China | 0.312 [0.083, 0.510] | 0.149 [0.026, 0.267] | 0.241 [0.157, 0.322] | −0.229 [−0.310, −0.144] | ||||

| CAAS-SF | 0.259 [0.163, 0.350] | 0.010 [−0.134, 0.153] | 0.230 [0.157, 0.300] | n/a | ||||

| Other measure 1 | 0.263 [0.158, 0.361] | n/a | n/a | n/a | ||||

| Other measure 2 | 0.013 [−0.113, 0.138] | n/a | n/a | n/a | ||||

| Other measure 3 | n/a | −0.068 [−0.178, 0.044] | n/a | n/a | ||||

| Family Variables | Parameter | r [LL, UL] | SE | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family support | b0 | −0.1744 [−0.4914, 0.1426] | 0.1617 | −1.08 |

| b1 | 0.3467 [0.1979, 0.4955] | 0.0759 | 4.57 | |

| QMold (1, k = 9) = 1.16, p > 0.05 | ||||

| Family SES | b0 | 0.2543 [−0.6852, 1.1937] | 0.4793 | 0.53 |

| b1 | −0.0087 [−0.4762, 0.4589] | 0.2386 | −0.04 | |

| QMold (1, k = 12) = 0.28, p > 0.05 | ||||

| PCB support | b0 | −0.4851 [−2.1422, 1.1719] | 0.4635 | −0.57 |

| b1 | 0.6010 [−0.3075, 1.5094] | 0.8454 | 1.30 | |

| QMold (1, k = 8) = 0.33, p > 0.05 | ||||

| PCB lack of engagement | b0 | −0.2936 [−1.3774, 0.7902] | 0.5530 | −0.53 |

| b1 | 0.0253 [−0.5550, 0.6055] | 0.2961 | 0.09 | |

| QMold (1, k = 7) = 0.28, p > 0.05 | ||||

| Family Variables | Parameter | r [LL, UL] | SE | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family support | b0 | 0.0069 [−0.0035, 0.0173] | 0.0053 | 1.31 |

| b1 | −13.6661 [−34.5726, 7.2405] | 10.6668 | −1.28 | |

| QMold (1, k = 9) = 1.71, p > 0.05 | ||||

| Family SES | b0 | 0.0153 [0.0029, 0.0277] | 0.0063 | 2.42 |

| b1 | −30.8709 [−55.9305, −5.8144] | 12.7857 | −2.41 | |

| QMold (1, k = 12) = 5.87, p < 0.05 | ||||

| PCB support | b0 | 0.0321 [0.0051, 0.0591] | 0.0138 | 2.33 |

| b1 | −64.5544 [−119.0663, −10.0425] | 27.8127 | −2.32 | |

| QMold (1, k = 8) = 5.44, p < 0.05 | ||||

| PCB lack of engagement | b0 | 0.0114 [−0.0287, 0.0514] | 0.0204 | 0.56 |

| b1 | −23.1194 [−104.0234, 57.7845] | 41.2783 | −0.56 | |

| QMold (1, k = 7) = 0.31, p > 0.05 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Z.; Dong, W. Relationship between Family Variables and Career Adaptability: A Meta-Analysis. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 840. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090840

Wang Z, Dong W. Relationship between Family Variables and Career Adaptability: A Meta-Analysis. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(9):840. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090840

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Zhuoxi, and Wei Dong. 2024. "Relationship between Family Variables and Career Adaptability: A Meta-Analysis" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 9: 840. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090840

APA StyleWang, Z., & Dong, W. (2024). Relationship between Family Variables and Career Adaptability: A Meta-Analysis. Behavioral Sciences, 14(9), 840. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090840