The Relationship between Laissez-Faire Leadership and Cyberbullying at Work: The Role of Interpersonal Conflicts

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Laissez-Faire Leadership and Cyberbullying

1.2. Interpersonal Conflicts and Cyberbullying

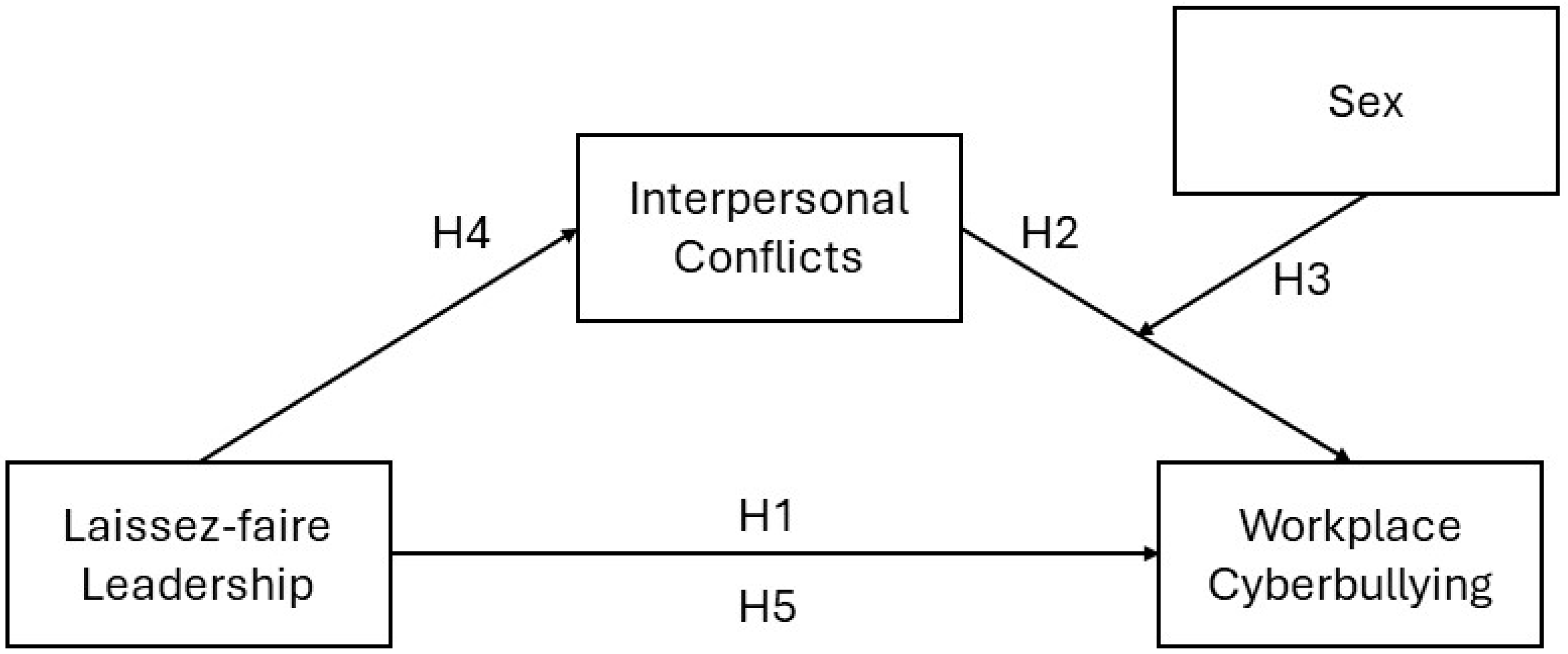

1.3. Laissez-Faire Leadership, Interpersonal Conflicts and Cyberbullying

1.4. Aims and Goals

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data Analysis

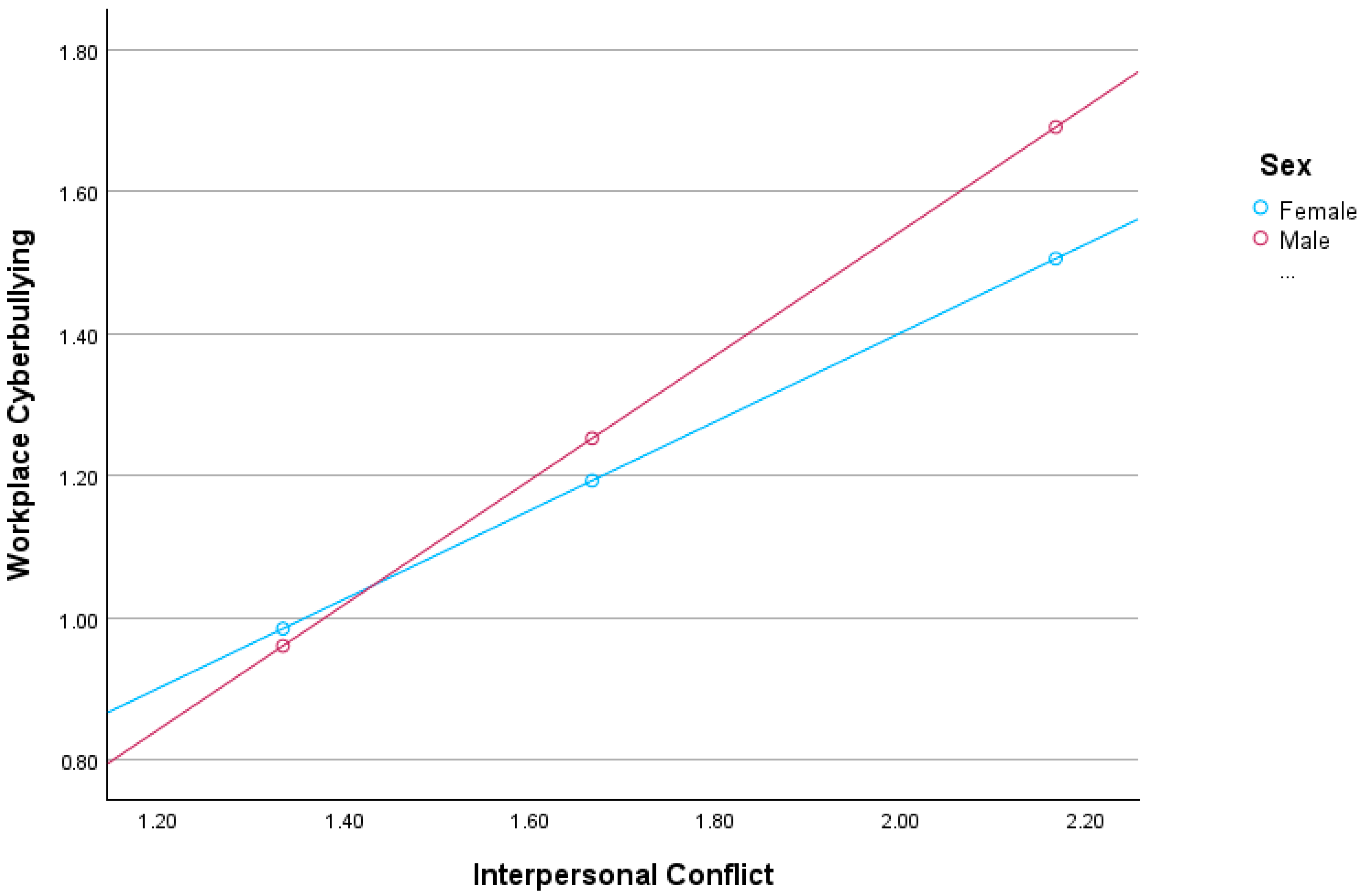

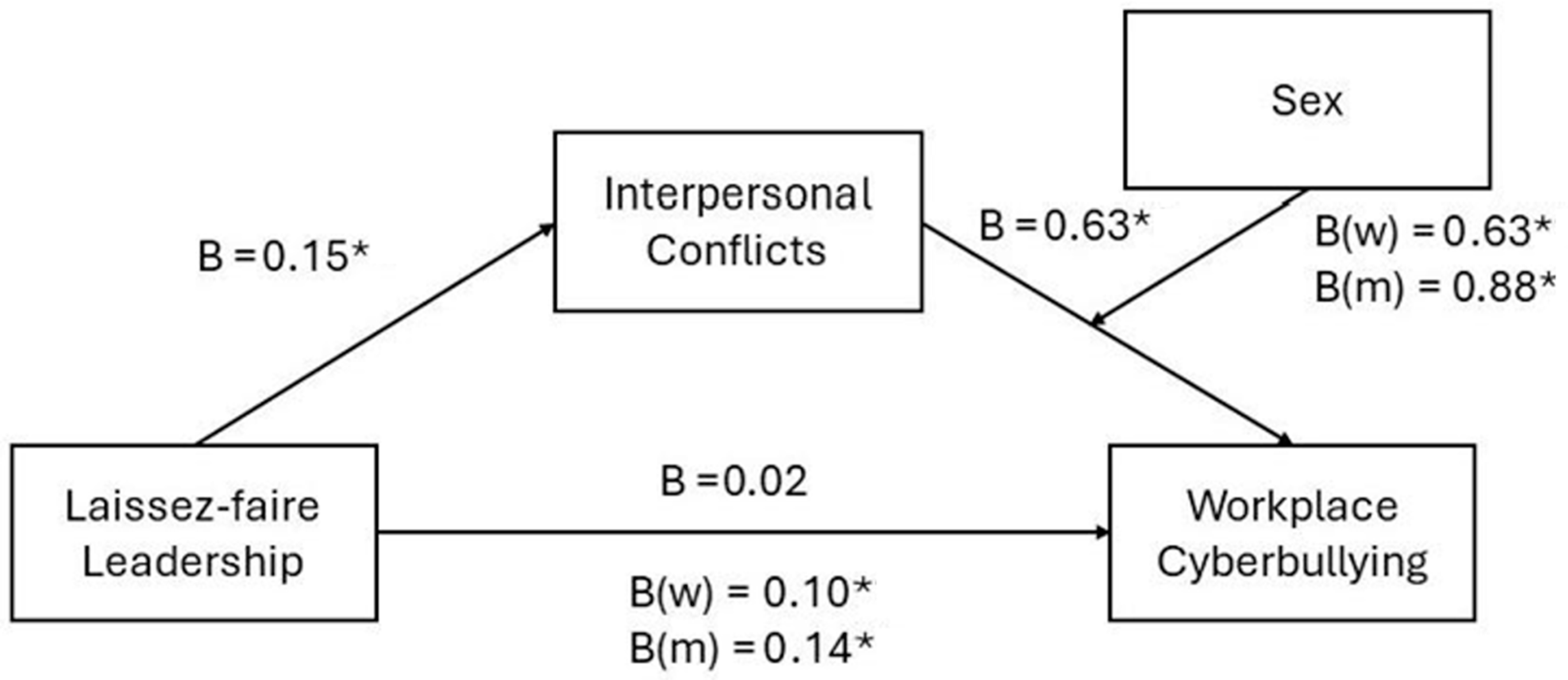

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eurofound. Living, Working and COVID-19 (Update April 2021): Mental Health and Trust Decline across EU as Pandemic Enters Another Year. Factsheet. COVID-19 Series, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. 2021. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/2021/living-working-and-covid-19-update-april-2021-mental-health-and-trust-decline (accessed on 19 June 2024).

- Lieberman, A.; Schroeder, J. Two social lives: How differences between online and offline interaction influence social outcomes. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 31, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Cruz, P.; Noronha, E. Mapping “Varieties of Workplace Bullying”: The Scope of the Field. In Concepts, Approaches and Methods. Handbooks of Workplace Bullying, Emotional Abuse and Harassment; D’Cruz, P., Noronha, E., Notelaers, G., Rayner, C., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; Volume 1, pp. 10–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vranjes, I.; Baillien, E.; Vandebosch, H.; Erreygers, S.; De Witte, H. The dark side of working online: Towards a definition and an emotion reaction model of workplace cyberbullying. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 69, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byron, K. Carrying too heavy a load? The communication and miscommunication of emotion by email. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Cruz, P. Cyberbullying at Work: Experiences of Indian Employees. In Virtual Workers and the Global Labour Market. Dynamics of Virtual Work; Webster, J., Randle, K., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, C.; Loh, J. Workplace cyberbullying and bystander helping behaviour. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 31, 2434–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platts, J.; Coyne, I.; Farley, S. Cyberbullying at work: An extension of traditional bullying or a new threat? Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2023, 16, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celuch, M.; Oksa, R.; Savela, N.; Oksanen, A. Longitudinal effects of cyberbullying at work on well-being and strain: A five-wave survey study. New Media Soc. 2024, 26, 3410–3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.C.; Chien-Hou, L.; Hwang, M.Y.; Hu, R.P.; Chen, Y.L. Positive affect predicting worker psychological response to cyber-bullying in the high-tech industry in Northern Taiwan. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 30, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, A.N.M.; Ho, H.C.Y.; Hou, W.K.; Poon, K.T.; Kwan, J.L.Y.; Chan, Y.C. A 1-year longitudinal study on experiencing workplace cyberbullying, affective well-being and work engagement of teachers: The mediating effect of cognitive reappraisal. Appl. Psychology. Health Well-Being 2024, aphw.12546, Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, W.; Qammar, A.; Shafique, I.; Anjum, Z.-U. Effect of cyberbullying on employee creativity: Examining the roles of family social support and job burnout. Foresight 2022, 24, 596–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyman, R.; Loh, J. Cyberbullying at work: The mediating role of optimism between cyberbullying and job outcomes. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 53, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, R.M.; Toth, A.; Morgan, M. Bullying and cyberbullying in adulthood and the workplace. J. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 158, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.; Fritz, C.; Jex, S.M. Daily cyber incivility and distress: The moderating roles of resources at work and home. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 2535–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, S.; Coyne, I.; D’Cruz, P. Cyberbullying at work: Understanding the influence of technology. In Concepts, Approaches and Methods. Handbooks of Workplace Bullying, Emotional Abuse and Harassment; D’Cruz, P., Noronha, E., Notelaers, G., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; Volume 1, pp. 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vranjes, I.; Farley, S.; Baillien, E. Harassment in the digital world: Cyberbullying. In Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace: Theory, Research and Practice, 3rd ed.; Einarsen, S.V., Hoel, H., Zapf, D., Cooper, C.L., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 409–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Bass, B.M.; Jung, D.I. Re-examining the components of transformational and transactional leadership using the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1999, 72, 441–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J. Developing transformational leadership: 1992 and beyond. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 1990, 14, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsen, S. The nature and causes of bullying at work. Int. J. Manpow. 1999, 20, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leymann, H. Mobbing and psychological terror at workplaces. Violence Vict. 1990, 5, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leymann, H. The content and development of mobbing at work. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 1996, 5, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsen, S.; Hoel, H.; Notelaers, G. Measuring exposure to bullying and harassment at work: Validity, factor structure and psychometric properties of the negative acts questionnaire revised. Work Stress 2009, 23, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoel, H.; Glasø, L.; Hetland, J.; Cooper, C.L.; Einarsen, S. Leadership styles as predictors of self-reported and observed workplace bullying. Br. J. Manag. 2010, 21, 453–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauge, L.J.; Skogstad, A.; Einarsen, S. Relationships between stressful work environments and bullying: Results of a large representative study. Work Stress 2007, 21, 220–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skogstad, A.; Einarsen, S.; Torsheim, T.; Aasland, M.S.; Hetland, H. The destructiveness of laissez-faire leadership behaviour. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2007, 12, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feijó, F.R.; Gräf, D.D.; Pearce, N.; Fassa, A.G. Risk factors for workplace bullying: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keashly, L.; Minkowitz, H.; Nowell, B.L. Conflict, conflict resolution and workplace bullying. In Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace: Theory, Research and Practice, 3rd ed.; Einarsen, S.V., Hoel, H., Zapf, D., Cooper, C.L., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 331–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollis, L.P. Lessons from Bandura’s Bobo Doll experiments: Leadership’s deliberate indifference exacerbates workplace bullying in higher education. J. Study Postsecond. Tert. Educ. 2019, 4, 085–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zapf, D.; Gross, C. Conflict escalation and coping with workplace bullying: A replication and extension. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2001, 10, 497–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillien, E.; Camps, J.; Van den Broeck, A.; Stouten, J.; Godderis, L.; Sercu, M.; De Witte, H. An eye for an eye will make the whole world blind: Conflict escalation into workplace bullying and the role of distributive conflict behaviour. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 137, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon-Perez, J.M.; Medina, F.J.; Arenas, A.; Munduate, L. The relationship between interpersonal conflict and workplace bullying. J. Manag. Psychol. 2015, 30, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notelaers, G.; Van der Heijden, B.; Guenter, H.; Nielsen, M.B.; Einarsen, S.V. Do interpersonal conflict, aggression and bullying at the workplace overlap? A latent class modeling approach. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahlquist, L.; Hetland, J.; Einarsen, S.V.; Bakker, A.B.; Hoprekstad, Ø.L.; Espevik, R.; Olsen, O.K. Daily interpersonal conflicts and daily exposure to bullying behaviours at work: The moderating roles of trait anger and trait anxiety. Appl. Psychol. 2023, 72, 893–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCord, M.A.; Joseph, D.L.; Dhanani, L.Y.; Beus, J.M. A meta-analysis of sex and race differences in perceived workplace mistreatment. J. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 103, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forssell, R.C. Exploring cyberbullying and face-to-face bullying in working life–Prevalence, targets and expressions. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 58, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, D.; O’Driscoll, M.; Cooper-Thomas, H.D.; Roche, M.; Bentley, T.; Catley, B.; Teo, S.T.; Trenberth, L. Predictors of Workplace Bullying and Cyber-Bullying in New Zealand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heatherington, W.; Coyne, I. Understanding individual experiences of cyberbullying encountered through work. Int. J. Organ. Theory Behav. 2014, 17, 163–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glambek, M.; Skogstad, A.; Einarsen, S. Workplace bullying, the development of job insecurity and the role of laissez-faire leadership: A two-wave moderated mediation study. Work Stress 2018, 32, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ågotnes, K.W.; Skogstad, A.; Hetland, J.; Olsen, O.K.; Espevik, R.; Bakker, A.B.; Einarsen, S.V. Daily work pressure and exposure to bullying-related negative acts: The role of daily transformational and laissez-faire leadership. Eur. Manag. J. 2021, 39, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namie, G.; Lutgen-Sandvik, P. Active and passive accomplices: The communal character of workplace bullying. Int. J. Commun. 2010, 4, 343–373. [Google Scholar]

- Vranjes, I.; Griep, Y.; Fortin, M.; Notelaers, G. Dynamic and multi-party approaches to interpersonal workplace mistreatment research. Group Organ. Manag. 2023, 48, 995–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notelaers, G. Workplace bullying: A risk control perspective. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto-Guerrero, M.; Antino, M.; Leon-Perez, J.M. Validation of the Spanish version of the intragroup conflict scale (ICS-14) A multilevel factor structure. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2019, 30, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vranjes, I.; Baillien, E.; Vandebosch, H.; Erreygers, S.; De Witte, H. When workplace bullying goes online: Construction and validation of the Inventory of Cyberbullying Acts at Work (ICA-W). Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2018, 27, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuno, K.; Kawakami, N. Multifactor leadership styles and new exposure to workplace bullying: A six-month prospective study. Ind. Health 2015, 53, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dussault, M.; Frenette, É. Supervisors’ transformational leadership and bullying in the workplace. Psychol. Rep. 2015, 117, 724–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.B. Bullying in work groups: The impact of leadership. Scand. J. Psychol. 2013, 54, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ågotnes, K.W.; Einarsen, S.V.; Hetland, J.; Skogstad, A. The moderating effect of laissez-faire leadership on the relationship between co-worker conflicts and new cases of workplace bullying: A true prospective design. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2018, 28, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillien, E.; Neyens, I.; De Witte, H.; De Cuyper, N.A. qualitative study on the development of workplace bullying: Towards a three way model. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 19, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salin, D.; Baillien, E.; Notelaers, G. High-performance work practices and interpersonal relationships: Laissez-faire leadership as a risk factor. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 854118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Halbesleben, J.; Neveu, J.P.; Westman, M. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, W.; Faucher, C.; Jackson, M. The dark side of the ivory tower: Cyberbullying of university faculty and teaching personnel. Alta. J. Educ. Res. 2015, 60, 279–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSouza, E.R. Frequency rates and correlates of contrapower harassment in higher education. J. Interpers. Violence 2011, 26, 158–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagsi, R.; Griffith, K.; Krenz, C.; Jones, R.D.; Cutter, C.; Feldman, E.L.; Jacobson, C.; Kerr, E.; Paradis, K.C.; Singer, K.; et al. Workplace Harassment, Cyber Incivility, and Climate in Academic Medicine. JAMA 2023, 329, 1848–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, N.; Forsyth, D.; Blackwood, K. Workplace cyber abuse: Challenges and implications for management. Pers. Rev. 2021, 50, 1774–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.; Koehler, C.; Schnauber-Stockmann, A. Why Should I Help You? Man Up! Bystanders’ Gender Stereotypic Perceptions of a Cyberbullying Incident. Deviant Behav. 2018, 40, 585–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, J.; Thibault, T.; Kelloway, E.K. Occupational health and safety leadership. In Handbook of Occupational Health Psychology, 3rd ed.; Tetrick, L.E., Fisher, G.G., Ford, M.T., Quick, J.C., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; pp. 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plimmer, G.; Nguyen, D.; Teo, S.; Tuckey, M.R. Workplace bullying as an organisational issue: Aligning climate and leadership. Work Stress 2021, 36, 202–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliday, C.S.; Paustian-Underdahl, S.C.; Stride, C.; Zhang, H. Retaining women in male-dominated occupations across cultures: The role of supervisor support and psychological safety. Hum. Perform. 2022, 35, 156–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, R.T.; Kombeiz, O.; Dollard, M. Manager-driven intervention for improved psychosocial safety climate and psychosocial work environment. Saf. Sci. 2024, 176, 106552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Pérez, J.M.; Arenas, A.; Griggs, T.B. Effectiveness of conflict management training to prevent workplace bullying. In Workplace Bullying: Symptoms and Solutions; Tehrani, N., Ed.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2012; pp. 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Pérez, J.M.; Ruiz-Zorrilla, P.; Notelaers, G.; Baillien, E.; Escartín, J.; Antino, M. Workplace bullying and harassment as group dynamic processes: A multilevel approach. Concepts, Approaches and Methods. In Concepts, Approaches and Methods. Handbooks of Workplace Bullying, Emotional Abuse and Harassment; D’Cruz, P., Noronha, E., Notelaers, G., Rayner, C., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; Volume 1, pp. 425–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantero-Sánchez, F.J.; León-Rubio, J.M.; Vázquez-Morejón, R.; León-Pérez, J.M. Evaluation of an assertiveness training based on the social learning theory for occupational health, safety and environment practitioners. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon-Perez, J.M.; Notelaers, G.; Leon-Rubio, J.M. Assessing the effectiveness of conflict management training in a health sector organization: Evidence from subjective and objective indicators. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2016, 25, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forssell, R.C. Gender and organisational position: Predicting victimisation of cyberbullying behaviour in working life. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 31, 2045–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salin, D.; Hoel, H. Workplace bullying as a gendered phenomenon. J. Manag. Psychol. 2013, 28, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sex | 0.46 | 0.50 | - | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.08 * |

| 2. Laissez faire leadership | 2.65 | 0.86 | - | 0.26 * | 0.17 * | |

| 3. Interpersonal conflict | 1.79 | 0.51 | - | 0.55 * | ||

| 4. Cyberbullying | 1.32 | 0.69 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cárdenas-Miyar, A.; Cantero-Sánchez, F.J.; León-Rubio, J.M.; Orgambídez-Ramos, A.; León-Pérez, J.M. The Relationship between Laissez-Faire Leadership and Cyberbullying at Work: The Role of Interpersonal Conflicts. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 824. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090824

Cárdenas-Miyar A, Cantero-Sánchez FJ, León-Rubio JM, Orgambídez-Ramos A, León-Pérez JM. The Relationship between Laissez-Faire Leadership and Cyberbullying at Work: The Role of Interpersonal Conflicts. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(9):824. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090824

Chicago/Turabian StyleCárdenas-Miyar, Alfonso, Francisco J. Cantero-Sánchez, José M. León-Rubio, Alejandro Orgambídez-Ramos, and Jose M. León-Pérez. 2024. "The Relationship between Laissez-Faire Leadership and Cyberbullying at Work: The Role of Interpersonal Conflicts" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 9: 824. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090824

APA StyleCárdenas-Miyar, A., Cantero-Sánchez, F. J., León-Rubio, J. M., Orgambídez-Ramos, A., & León-Pérez, J. M. (2024). The Relationship between Laissez-Faire Leadership and Cyberbullying at Work: The Role of Interpersonal Conflicts. Behavioral Sciences, 14(9), 824. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090824