Mechanisms Linking Social Media Use and Sleep in Emerging Adults in the United States

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Emotional Investment in Social Media

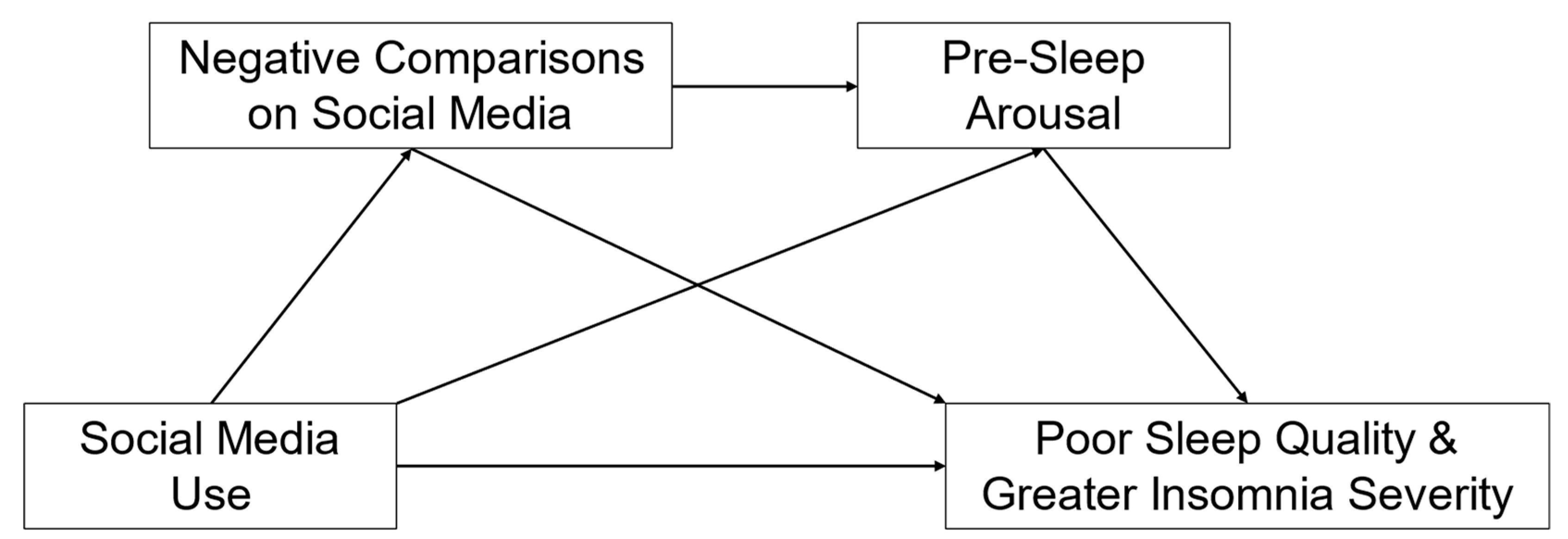

1.2. Mechanisms Linking Social Media and Sleep

1.3. Aims and Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Social Media Use

2.2.2. Sleep Characteristics

2.2.3. Negative Social Comparison on Social Media

2.2.4. Pre-Sleep Arousal

2.2.5. Demographic Characteristics

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analyses

3.2. Aim 1: Association of Social Media Use and Sleep Characteristics

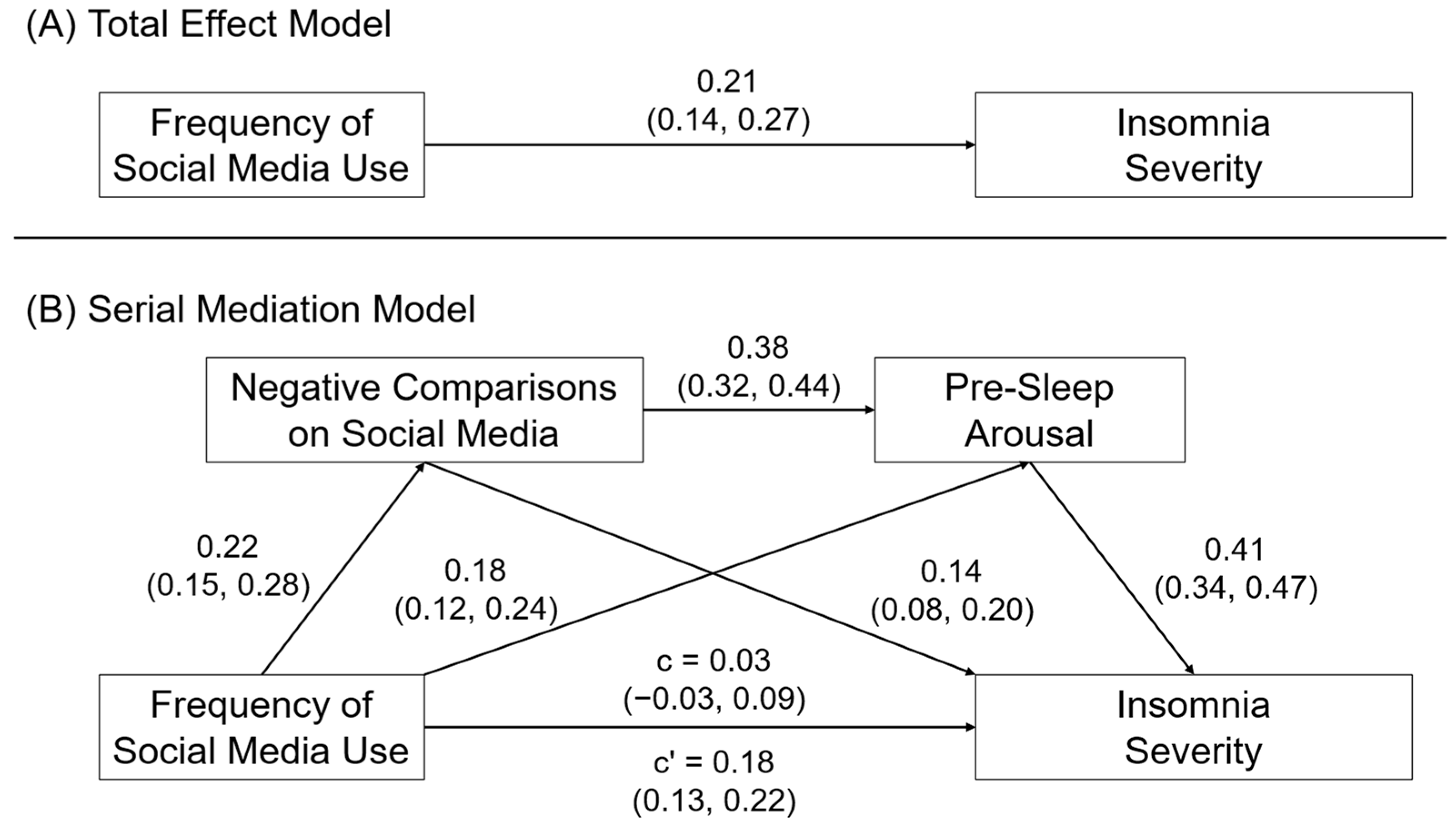

3.3. Aim 2: Mechanisms Linking Social Media Use and Sleep Characteristics

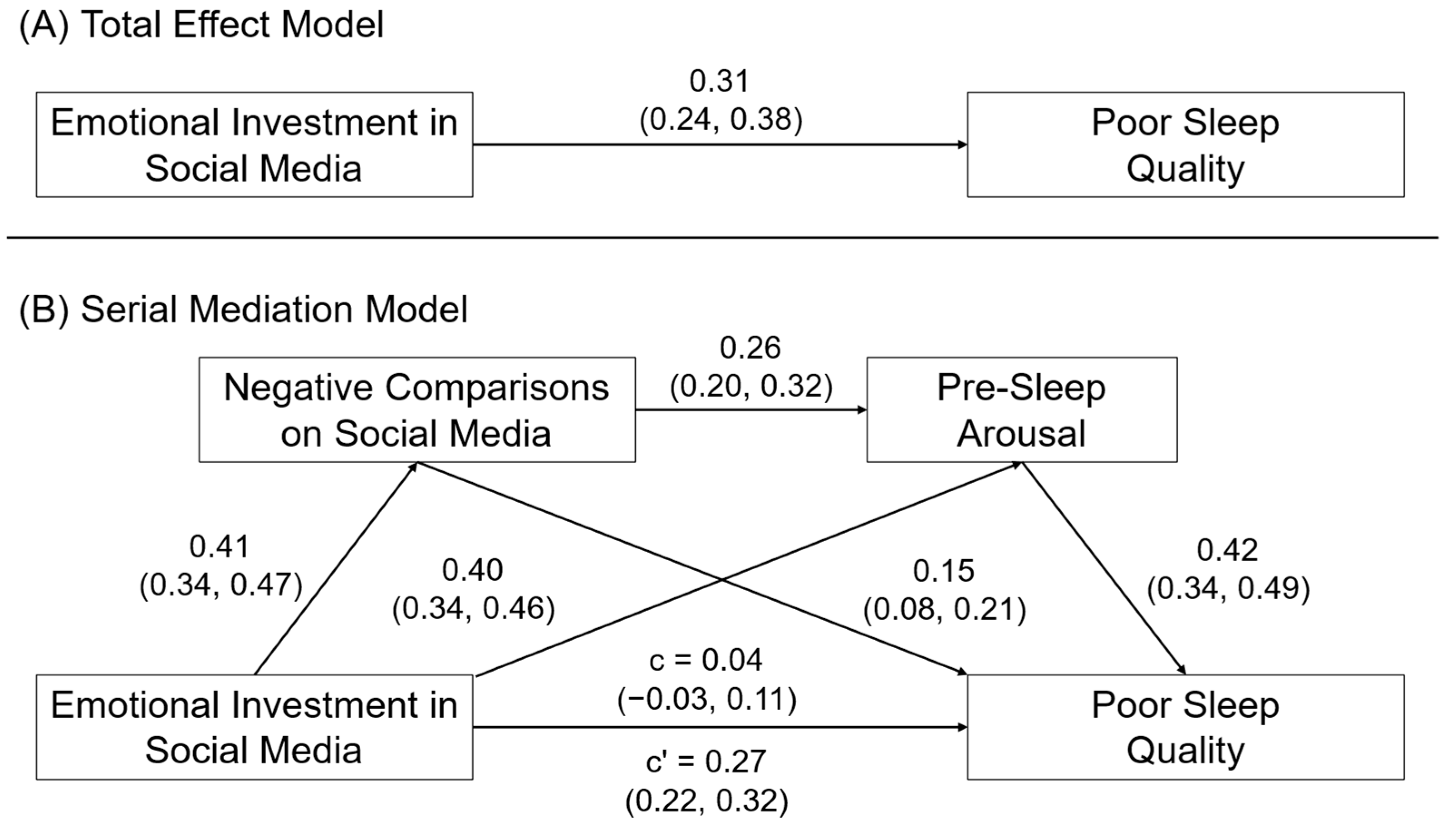

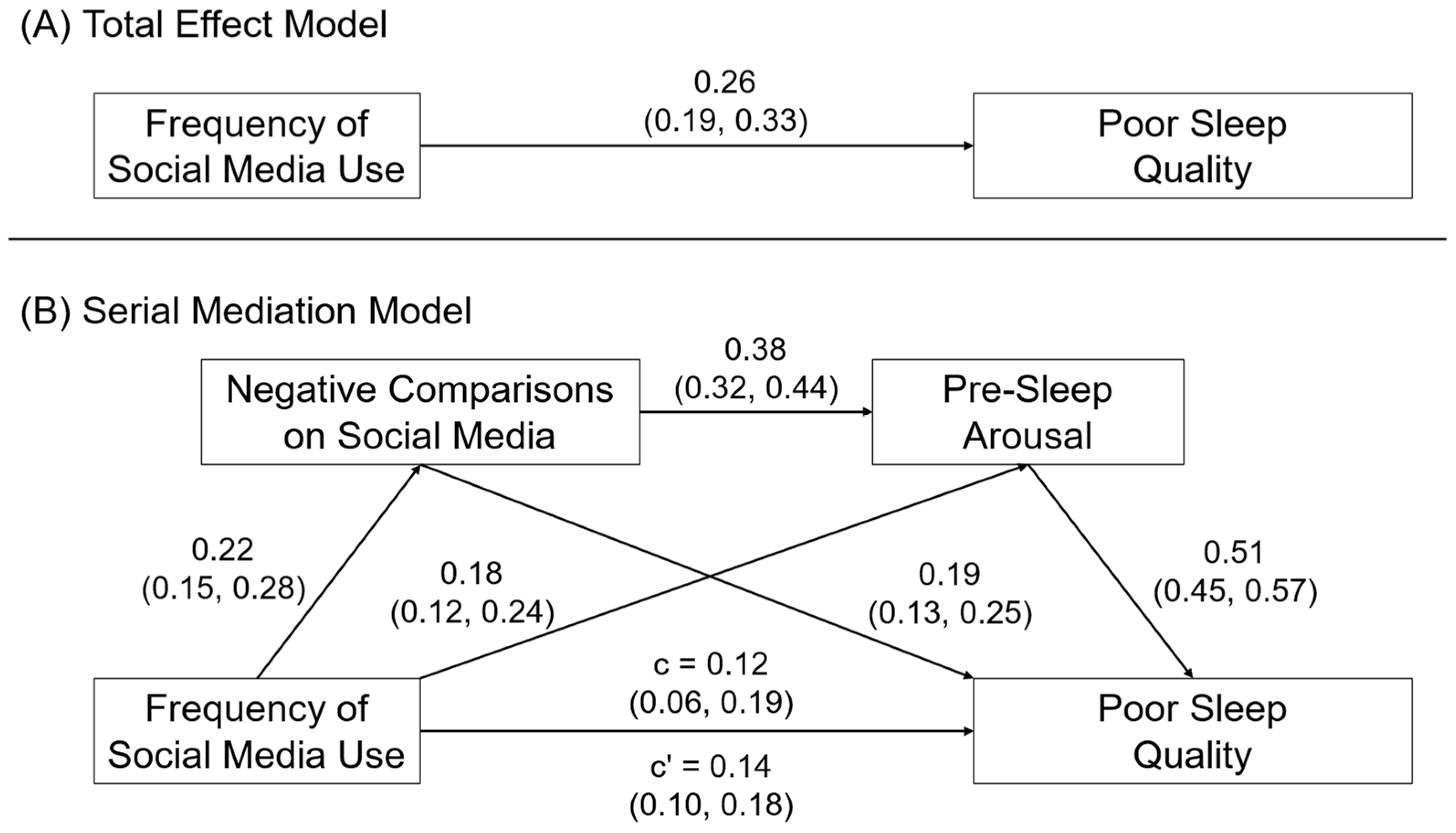

3.3.1. Sleep Quality

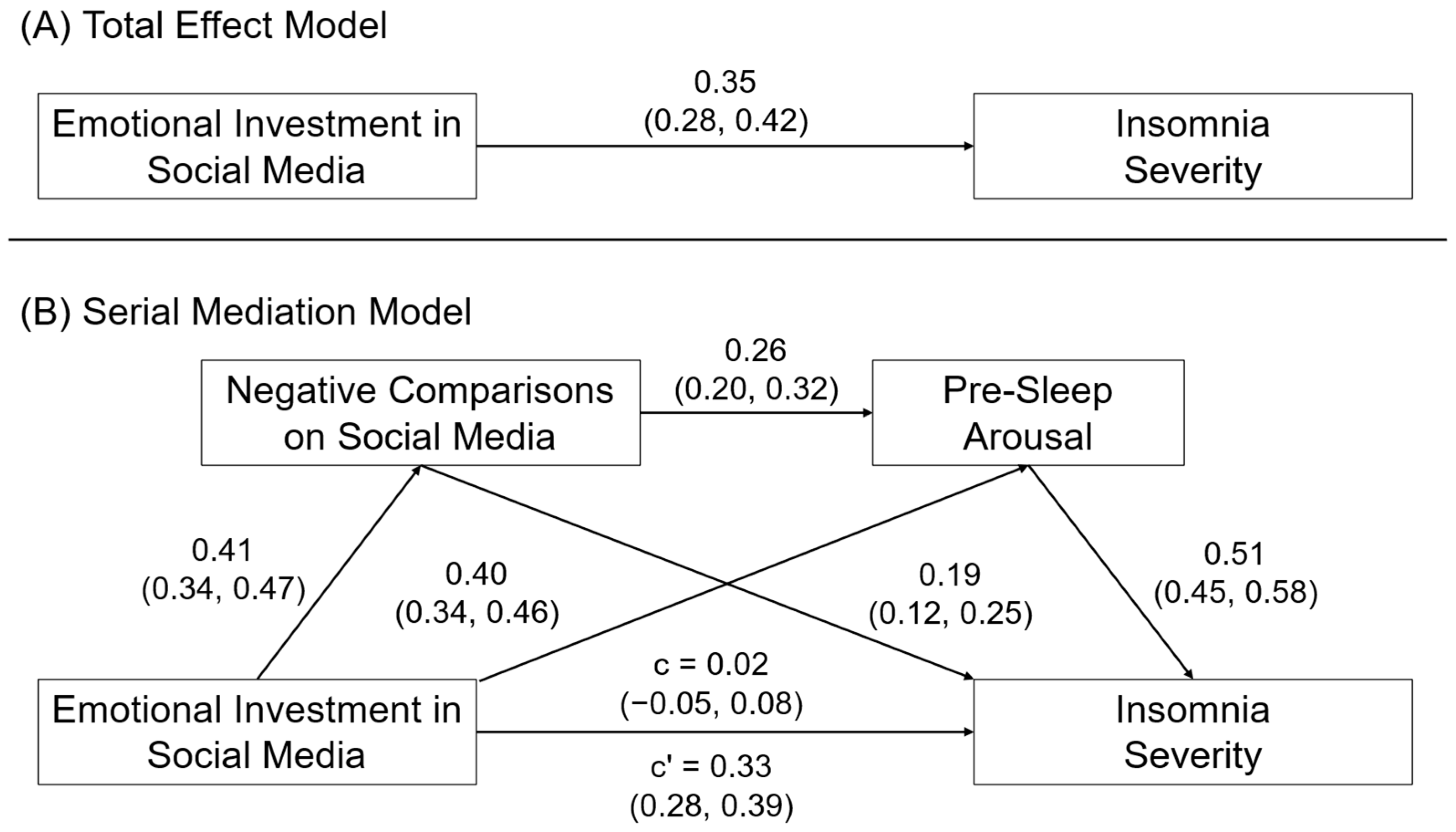

3.3.2. Insomnia Severity

4. Discussion

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Owens, J.; Adolescent Sleep Working Group; Committee on Adolescence; Au, R.; Carskadon, M.; Millman, R.; Wolfson, A.; Braverman, P.K.; Adelman, W.P.; Breuner, C.C.; et al. Insufficient Sleep in Adolescents and Young Adults: An Update on Causes and Consequences. Pediatrics 2014, 134, e921–e932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradisar, M.; Wolfson, A.R.; Harvey, A.G.; Hale, L.; Rosenberg, R.; Czeisler, C.A. The Sleep and Technology Use of Americans: Findings from the National Sleep Foundation’s 2011 Sleep in America Poll. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2013, 9, 1291–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, A.; Mangal, R.; Stead, T.S.; Walker, J.; Ganti, L. The extent of sleep deprivation and daytime sleepiness in young adults. Health Psychol. Res. 2023, 11, 74555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonzo, R.; Hussain, J.; Stranges, S.; Anderson, K.K. Interplay between social media use, sleep quality, and mental health in youth: A systematic review. Sleep Med. Rev. 2021, 56, 101414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auxier, B.; Anderson, M. Social Media Use in 2021; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, D.J.; Wing, Y.K.; Li, T.M.H.; Chan, N.Y. The Impact of Social Media Use on Sleep and Mental Health in Youth: A Scoping Review. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2024, 26, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levenson, J.C.; Shensa, A.; Sidani, J.E.; Colditz, J.B.; Primack, B.A. The association between social media use and sleep disturbance among young adults. Prev. Med. 2016, 85, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, H.; Biello, S.M.; Woods, H.C. Social media use and adolescent sleep patterns: Cross-sectional findings from the UK millennium cohort study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e031161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, H.; Woods, H.C. Fear of missing out and sleep: Cognitive behavioural factors in adolescents’ nighttime social media use. J. Adolesc. 2018, 68, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levenson, J.C.; Shensa, A.; Sidani, J.E.; Colditz, J.B.; Primack, B.A. Social Media Use Before Bed and Sleep Disturbance among Young Adults in the United States: A Nationally Representative Study. Sleep 2017, 40, zsx113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, H.C.; Scott, H. #Sleepyteens: Social media use in adolescence is associated with poor sleep quality, anxiety, depression and low self-esteem. J. Adolesc. 2016, 51, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsunni, A.A.; Latif, R. Higher emotional investment in social media is related to anxiety and depression in university students. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2021, 16, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Festinger, L. A Theory of Social Comparison Processes. Hum. Relat. 1954, 7, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNee, S.; Woods, H.C. Pre-sleep Cognitive Influence of Night-time Social Media Use and Social Comparison Behaviour in Young Women. PsyArXiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reer, F.; Tang, W.Y.; Quandt, T. Psychosocial well-being and social media engagement: The mediating roles of social comparison orientation and fear of missing out. New Media Soc. 2019, 21, 1486–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, E.A.; Rose, J.P.; Okdie, B.M.; Eckles, K.; Franz, B. Who compares and despairs? The effect of social comparison orientation on social media use and its outcomes. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 86, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verduyn, P.; Gugushvili, N.; Massar, K.; Täht, K.; Kross, E. Social comparison on social networking sites. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 36, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnell, K.; George, M.J.; Vollet, J.W.; Ehrenreich, S.E.; Underwood, M.K. Passive social networking site use and well-being: The mediating roles of social comparison and the fear of missing out. Cyberpsychol. J. Psychosoc. Res. Cyberspace 2019, 13, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-L.; Wang, H.-Z.; Gaskin, J.; Hawk, S. The Mediating Roles of Upward Social Comparison and Self-esteem and the Moderating Role of Social Comparison Orientation in the Association between Social Networking Site Usage and Subjective Well-Being. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dibb, B.; Foster, M. Loneliness and Facebook use: The role of social comparison and rumination. Heliyon 2021, 7, e05999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, D.A.; Möller, A.M.; Wieringa, M.S.; Eigenraam, A.W.; Hamelink, K. Social Comparison as the Thief of Joy: Emotional Consequences of Viewing Strangers’ Instagram Posts. Media Psychol. 2018, 21, 222–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exelmans, L.; Van Den Bulck, J. Binge Viewing, Sleep, and the Role of Pre-Sleep Arousal. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2017, 13, 1001–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SafeToNet Foundation. (n.d.). TikTok. Available online: https://safetonetfoundation.org/app-risks/tiktok/ (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Wang, K.; Scherr, S. Dance the Night Away: How Automatic TikTok Use Creates Pre-Sleep Cognitive Arousal and Daytime Fatigue. Mob. Media Commun. 2022, 10, 316–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbard, E.; Allen, N.B.; Trinder, J.; Bei, B. What’s Keeping Teenagers Up? Prebedtime Behaviors and Actigraphy-Assessed Sleep Over School and Vacation. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 58, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, F.; Marques, D.R.; Gomes, A.A. A preliminary study on the association between social media at night and sleep quality: The relevance of FOMO, cognitive pre-sleep arousal, and maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation. Scand. J. Psychol. 2023, 64, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergfeld, N.S.; Van Den Bulck, J. It’s not all about the likes: Social media affordances with nighttime, problematic, and adverse use as predictors of adolescent sleep indicators. Sleep Health 2021, 7, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, J.; Rosenzweig, C.; Moss, A.J.; Robinson, J.; Litman, L. Online panels in social science research: Expanding sampling methods beyond Mechanical Turk. Behav. Res. Methods 2019, 51, 2022–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins-Guarnieri, M.A.; Wright, S.L.; Johnson, B. Development and validation of a social media use integration scale. Psychol. Pop. Media Cult. 2013, 2, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F.; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastien, C.H.; Vallières, A.; Morin, C.M. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001, 2, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samra, A.; Warburton, W.A.; Collins, A.M. Social comparisons: A potential mechanism linking problematic social media use with depression. J. Behav. Addict. 2022, 11, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicassio, P.M.; Mendlowitz, D.R.; Fussell, J.J.; Petras, L. The phenomenology of the pre-sleep state: The development of the pre-sleep arousal scale. Behav. Res. Ther. 1985, 23, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research. (n.d.). Social Media Fact Sheet. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/social-media/ (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Saelee, R.; Haardörfer, R.; Johnson, D.A.; Gazmararian, J.A.; Suglia, S.F. Racial/Ethnic and Sex/Gender Differences in Sleep Duration Trajectories from Adolescence to Adulthood in a US National Sample. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2023, 192, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales, A.L.; Hancock, J.T. Mirror, Mirror on my Facebook Wall: Effects of Exposure to Facebook on Self-Esteem. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2011, 14, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, S.; Engelhardt, M.; Schaupp, P.; Lappe, C.; Ivanov, I.V. The inner clock-Blue light sets the human rhythm. J. Biophotonics 2019, 12, e201900102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartanto, A.; Quek, F.Y.X.; Tng, G.Y.Q.; Yong, J.C. Does Social Media Use Increase Depressive Symptoms? A Reverse Causation Perspective. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 641934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, H.; Woods, H.C. Understanding Links Between Social Media Use, Sleep and Mental Health: Recent Progress and Current Challenges. Curr. Sleep Med. Rep. 2019, 5, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardefelt-Winther, D. A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaRose, R.; Lin, C.A.; Eastin, M.S. Unregulated Internet Usage: Addiction, Habit, or Deficient Self-Regulation? Media Psychol. 2003, 5, 225–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, E.; Donovan, E.K.; Soto, P.; Sabet, S.M.; Ravyts, S.G.; Dzierzewski, J.M. Trading likes for sleepless nights: A lifespan investigation of social media and sleep. Sleep Health 2021, 7, 474–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) or % (n) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 24.2 (3.9) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 63.1 (524) |

| Male | 35.9 (298) |

| Non-Binary | 1.0 (8) |

| Race and Ethnicity | |

| White | 54.0 (448) |

| Black or African American | 28.1 (233) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 15.8 (131) |

| Asian or Asian American | 4.9 (41) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 3.0 (25) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 0.2 (2) |

| Another Race or Ethnicity | 0.6 (5) |

| Multiple Races | 1.9 (16) |

| Educational attainment | |

| Less than high school | 6.3 (52) |

| High school or equivalent | 41.7 (346) |

| Some colleges, no degree | 24.9 (207) |

| Associate’s degree | 9.8 (81) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 14.3 (119) |

| Graduate degree | 3.0 (25) |

| Sleep characteristics | |

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index | 8.6 (3.9) |

| Insomnia Severity Scale | 11.3 (6.1) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kinsella, J.E.; Chin, B.N. Mechanisms Linking Social Media Use and Sleep in Emerging Adults in the United States. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 794. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090794

Kinsella JE, Chin BN. Mechanisms Linking Social Media Use and Sleep in Emerging Adults in the United States. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(9):794. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090794

Chicago/Turabian StyleKinsella, Joshua Ethan, and Brian N. Chin. 2024. "Mechanisms Linking Social Media Use and Sleep in Emerging Adults in the United States" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 9: 794. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090794

APA StyleKinsella, J. E., & Chin, B. N. (2024). Mechanisms Linking Social Media Use and Sleep in Emerging Adults in the United States. Behavioral Sciences, 14(9), 794. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090794