Ternary Moral Empathy Model from the Perspective of Intersubjective Phenomenology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Moral Empathy in Intersubjective Phenomenology

2.1. Phenomenology of Empathy

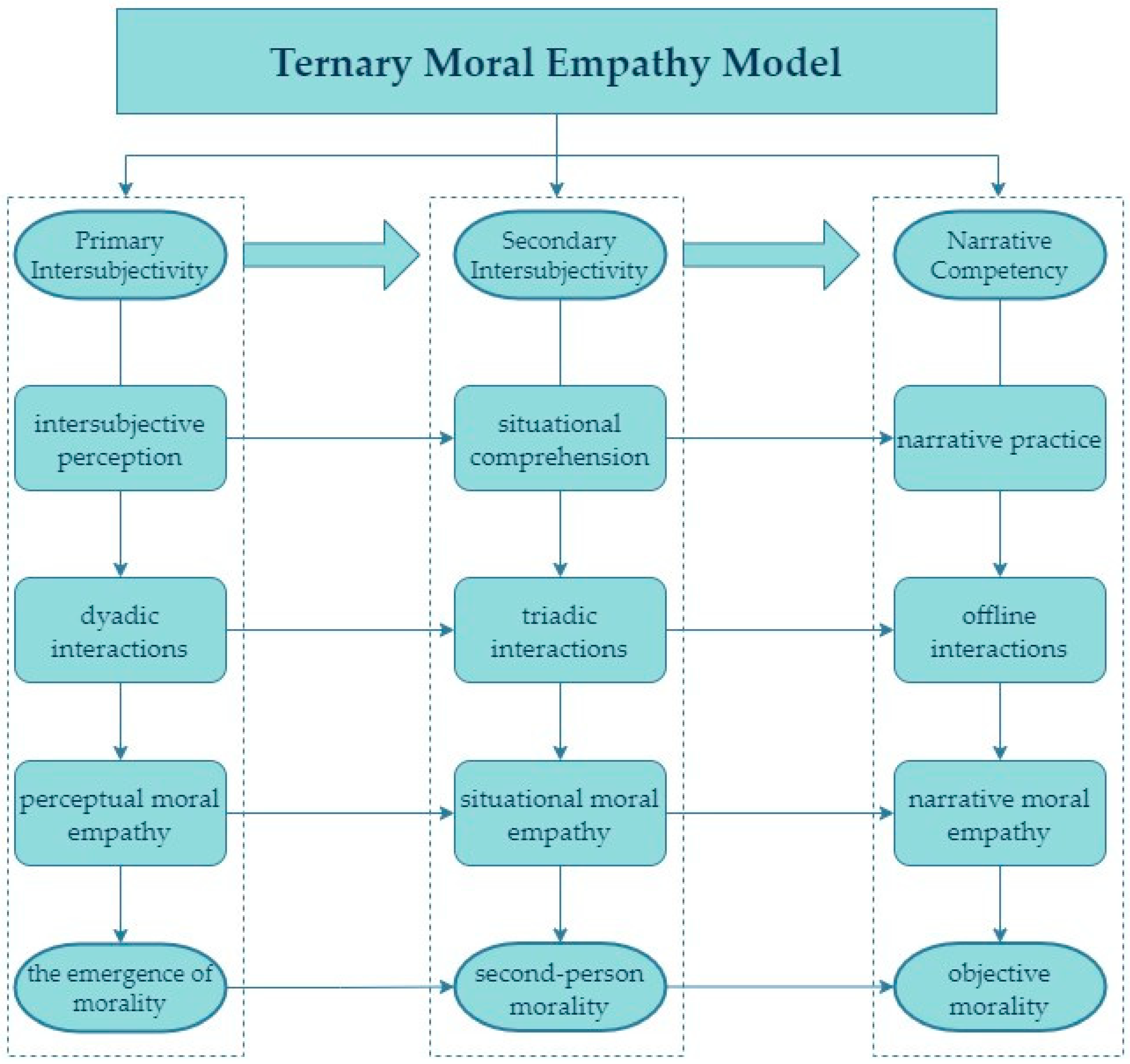

2.2. Ternary Moral Empathy Model

3. The Moral Dimension of Perceptual Empathy

3.1. Embodied Empathic Practices of Perception-Action Coupling

3.2. The Emergence of Moral Empathy

4. The Moral Dimension of Situational Empathy

4.1. The Formation of “We-Intentionality”

4.2. Dynamic Coupling of Embodied Situation and Moral Empathy

5. The Moral Dimension of Narrative Empathy

5.1. The “Lifeworld” as the Prototype of Empathic Narrative

5.2. Embodied Narratives as “Scaffolding” for Moral Empathy

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hall, J.A.; Schwartz, R. Empathy present and future. J. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 3, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, M.L. Empathy and Moral Development: Implications for Caring and Justice; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, S.D.; de Waal, F.B. Empathy: Its ultimate and proximate bases. Behav. Brain Sci. 2002, 25, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Waal, F.B.; Preston, S.D. Mammalian empathy: Behavioral manifestations and neural basis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2017, 18, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decety, J.; Lamm, C. Human empathy through the lens of social neuroscience. Sci. World J. 2006, 6, 1146–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decety, J.; Jackson, P. The functional architecture of human empathy. Behav. Cogn. Neurosci. Rev. 2004, 3, 71–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahavi, D.; Overgaard, S. Empathy without isomorphism: A phenomenological account. In Empathy: From Bench to Bedside; Decety, J., Ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, A.I. Imitation, Mind Reading, and Simulation. In Perspectives on Imitation II; Hurley, S., Chater, N., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005; pp. 79–93. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, S. Empathy, simulation, and narrative. Sci. Context 2012, 25, 355–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravenscroft, I. What is it like to be someone else? Simulation and empathy. Ratio 1998, 11, 170–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, F.R. Empathy, neural imaging and the theory versus simulation debate. Mind Lang. 2010, 16, 368–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decety, J.; Cowell, J.M. The complex relation between morality and empathy. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2014, 18, 337–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X. Empathy and Personality: Edith Stein’s Intersubjective Phenomenology; Jiangsu People’s Publishing House: Nanjing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, S. Inference or interaction: Social cognition without precursors. Philos. Explor. 2008, 11, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevarthan, C.; Hubley, P. Secondary intersubjectivity: Confidence, confiding, and acts of meaning in the first year. In Action, Gesture and Symbol: The Emergence of Language; Lock, A., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1978; pp. 183–229. [Google Scholar]

- Zahavi, D. Self and Other: Exploring Subjectivity, Empathy, and Shame; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, T.; Koch, S.C. Embodied affectivity: On moving and being moved. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombetti, G. The Feeling Body: Affective Science Meets the Enactive Mind; MIT Press: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Troncoso, A.; Soto, V.; Gomila, A.; Martínez-Pernía, D. Moving beyond the lab: Investigating empathy through the Empirical 5E approach. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1119469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Vondevoort, J.; Hamlin, J.K. The infantile roots of sociomoral evaluations. In Atlas of Moral Psychology; Gray, K., Graham, J., Eds.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 402–412. [Google Scholar]

- Waller, R.; Wagner, N.J.; Barstead, M.G.; Subar, A.; Petersen, J.L.; Hyde, J.S.; Hyde, L.W. A meta-analysis of the associations between callous-unemotional traits and empathy, prosociality, and guilt. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 75, 101809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, J. Empathy is a moral force. In Atlas of Moral Psychology; Gray, K., Graham, J., Eds.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Eva, J. Empathy or intersubjectivity? Understanding the origins of morality in young children’. Stud. Philos. Educ. 2008, 27, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevarthen, C. Communication and cooperation in early infancy: A description of primary intersubjectivity. In Before Speech: The Beginning of Interpersonal Communication; Bullowa, M.M., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979; pp. 321–348. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, S.; Meltzoff, A.N. The earliest sense of self and others: Merleau-Ponty and recent developmental studies. Philos. Psychol. 1996, 9, 211–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geangu, E.; Benga, O.; Stahl, D.; Striano, T. Individual differences in infant’s emotional resonance to a peer in distress: Self-other awareness and emotion regulation. Soc. Dev. 2011, 20, 450–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevarthen, C. The foundations of intersubjectivity: Development of interpersonal and cooperative understanding in infants. In The Social Foundations of Language and Thought: Essays in Honor of J. S. Bruner; Olson, D., Ed.; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1980; pp. 316–342. [Google Scholar]

- Trevarthen, C. What is it like to be a person who knows nothing? Defining the active intersubjective mind of a newborn human being. Infant Child Dev. 2011, 20, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, M. Interaction of affect and cognition in empathy. In Emotions, Cognition, and Behaviour; Izzard, C.E., Kagan, J., Zajonc, R., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1984; pp. 103–131. [Google Scholar]

- Farroni, T.; Menon, E.; Rigato, S.; Johnson, M.H. The perception of facial expressions in newborns. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2007, 4, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochat, P.; Striano, T. Social-cognitive development in the first year. In Early Social Cognition: Understanding Others in the First Months of Life; Rochat, P., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1999; pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Fogel, A.; Thelen, E. Development of early expressive and communicative action: Reinterpreting the evidence from a dynamic systems perspective. Dev. Psychol. 1987, 23, 747–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, L.; Trevarthen, C. Emotional regulation of interactions between two-month-olds and their mothers. In Social Perception in Infants; Field, T.M., Fox, N.A., Eds.; Ablex: Norwood, NJ, USA, 1985; pp. 177–197. [Google Scholar]

- Bateson, M.C. ‘The epigenesis of conversational interaction’: A personal account of research development. In Before Speech; Bullowa, M., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1975; pp. 63–77. [Google Scholar]

- Flom, R.; Bahrick, L.E. The development of infant discrimination of affect in multimodal and unimodal stimulation: The role of intersensory redundancy. Dev. Psychol. 2007, 43, 238–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, T. The development of emotion perception in face and voice during infancy. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 2010, 28, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senju, A.; Johnson, M.H.; Csibra, G. The development and neural basis of referential gaze perception. Soc. Neurosci. 2006, 1, 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvadori, E.A.; Colonnesi, C.; Vonk, H.S.; Oort, F.J.; Aktar, E. Infant emotional mimicry of strangers: Associations with parent emotional mimicry, parent-infant mutual attention, and parent dispositional affective empathy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallese, V.; Goldman, A. Mirror neurons and the simulation theory of mind-reading. Trends Cogn. Sci. 1998, 2, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, L.; Iacoboni, M.; Dubeau, M.C.; Mazziotta, J.C.; Lenzi, G.L. Neural mechanisms of empathy in humans: A relay from neural systems for imitation to limbic areas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 5497–5502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerville, J.A.; Decety, J. Weaving the fabric of social interaction: Articulating developmental psychology and cognitive neuroscience in the domain of motor cognition. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2006, 13, 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallese, V. The roots of empathy: The shared manifold hypothesis and the neural basis of intersubjectivity. Psychopathology 2003, 36, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallese, V. Bodily selves in relation: Embodied simulation as second-person perspective on intersubjectivity. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 369, 20130177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Pernía, D.; Cea, I.; Troncoso, A.; Blanco, K.; Calderón Vergara, J.; Baquedano, C.; Araya-Veliz, C.; Useros-Olmo, A.; Huepe, D.; Vergara, M. “I am feeling tension in my whole body”: An experimental phenomenological study of empathy for pain. Front. Psychol. 2024, 13, 999227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noll, L.K.; Linda, C.M.; Helena, J.V.R. Investigating the impact of parental status and depression symptoms on the early perceptual coding of infant faces: An event-related potential study. Soc. Neurosci. 2012, 7, 525–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belacchi, C.; Farina, E. Feeling and thinking of others: Affective and cognitive empathy and emotion comprehension in prosocial/hostile preschoolers. Aggress. Behav. 2012, 38, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidov, M.; Zahn-Waxler, C.; Roth-Hanania, R.; Knafo, A. Concern for others in the first year of life: Theory, evidence, and avenues for research. Child Dev. Perspect. 2013, 7, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddle, M.-J.E.; Bradley, B.S.; Mcgrath, A. Baby empathy: Infant distress and peer prosocial responses. Infant Ment. Health J. 2015, 36, 446–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decety, J.; Cowell, J.M. Interpersonal harm aversion as a necessary foundation for morality: A developmental neuroscience perspective. Dev. Psychopathol. 2018, 30, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidov, M.; Paz, Y.; Roth, H.R.; Uzefovsky, F.; Orlitsky, T.; Mankuta, D.; Zahn-Waxler, C. Caring babies: Concern for others in distress during infancy. Dev. Sci. 2021, 24, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamlin, J.K. The origins of human morality: Complex socio-moral evaluations by pre-verbal infants. In New Frontiers in Social Neuroscience; Decety, J., Christen, Y., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 165–188. [Google Scholar]

- Iacoboni, M. Imitation, empathy, and mirror neurons. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2009, 60, 653–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, E.; Mikami, A.Y.; Hamlin, J.K. Do infant sociomoral evaluation and action studies predict preschool social and behavioral adjustment? J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2018, 176, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decety, J.; Michalska, K.J.; Kinzler, K.D. The developmental neuroscience of moral sensitivity. Emot. Rev. 2011, 3, 305–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, E.; Rochat, P. Emerging signs of strong reciprocity in human ontogeny. Front. Psychol. 2011, 2, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z. Husserl’s Phenomenology of Empathy; Guangdong People’s Publishing House: Guangzhou, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, S. Situational understanding: A Gurwitschean critique of theory of mind. In Gurwitsch’s Relevancy for Cognitive Science; Embree, L., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, P.; Scarantino, A. Emotions in the wild. In The Cambridge Handbook of Situated Cognition; Robbins, P., Aydede, M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, NY, USA, 2009; p. 437. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, L.F.; Mesquita, B.; Gendron, M. Context in emotion perception. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 20, 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, A. Primary intersubjectivity: Empathy, affective reversibility, ‘self-affection’ and the primordial ‘we’. Topoi 2014, 33, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownell, C.A. Early developments in joint action. Rev. Philos. Psychol. 2011, 2, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, S. Two problems of intersubjectivity. J. Conscious. Stud. 2009, 16, 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decety, J.; Jackson, P.L.; Brunet, E. The cognitive neuropsychology of empathy. In Empathy in Mental Illness; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 239–260. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, N. Empathy-related responding: Its role in positive development and socialization correlates. In Approaches to Positive Youth Development; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Su, Y. The development of empathy across the lifespan: A perspective of double processes. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2012, 28, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decety, J.; Meyer, M. From emotion resonance to empathic understanding: A social developmental neuroscience account. Dev. Psychopathol. 2008, 20, 1053–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, A.H.; Simon, H.A. Situated action: A symbolic interpretation. Cogn. Sci. 1993, 17, 7–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen, D. The Second-Person Standpoint: Morality, Respect, and Accountability; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Svetlova, M.; Nichols, S.R.; Brownell, C.A. Toddlers’ prosocial behavior: From instrumental to empathic to altruistic helping. Child Dev. 2010, 81, 1814–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaish, A.; Grossmann, T.; Woodward, A. Not all emotions are created equal: The negativity bias in social-emotional development. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 134, 383–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlberg, L. The Psychology of Moral Development: The Nature and Validity of Moral Stages; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, N.; Mussen, P.H. The Roots of Prosocial Behavior in Children; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello, M. A Natural History of Human Morality; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, S. Action and Interaction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Trevarthen, C. Infant semiosis. In Origins of Semiosis; Noth, W., Ed.; Mouton de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 1994; pp. 219–252. [Google Scholar]

- Menary, R. Embodied narratives. J. Conscious. Stud. 2008, 15, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousta, S.T.; Vigliocco, G.; Vinson, D.P.; Andrews, M.; Del Campo, E. The representation of abstract words: Why emotion matters. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2011, 140, 14–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vigliocco, G.; Kousta, S.T.; Della Rosa, P.A.; Vinson, D.P.; Tettamanti, M.; Devlin, J.T.; Cappa, S.F. The neural representation of abstract words: The role of emotion. Cereb. Cortex 2014, 24, 1767–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scorolli, C.; Binkofski, F.; Buccino, G.; Nicoletti, R.; Riggio, L.; Borghi, A.M. Abstract and concrete sentences, embodiment, and languages. Front. Psychol. 2011, 2, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trainor, L.J. Infant preferences for infant-directed versus non-infant-directed play songs and lullabies. Infant Behav. Dev. 1996, 19, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakoff, G.; Johnson, M. Metaphors We Live by; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z. From somatic to semiotic: Triune embodied morality. Thought Cult. 2019, 1, 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, N.; Wu, P. On the mechanism of arousing emotional resonance by ethical narration. Moral. Civiliz. 2019, 1, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlin, D. Origins of the Modern Mind; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Fabry, R.E. Narrative Scaffolding. Rev. Philos. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1147–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukkonen, K. Probability Designs: Literature and Predictive Processing; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, Z.; Ma, X. Ternary Moral Empathy Model from the Perspective of Intersubjective Phenomenology. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 792. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090792

Zhao Z, Ma X. Ternary Moral Empathy Model from the Perspective of Intersubjective Phenomenology. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(9):792. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090792

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Zhihui, and Xiangzhen Ma. 2024. "Ternary Moral Empathy Model from the Perspective of Intersubjective Phenomenology" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 9: 792. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090792

APA StyleZhao, Z., & Ma, X. (2024). Ternary Moral Empathy Model from the Perspective of Intersubjective Phenomenology. Behavioral Sciences, 14(9), 792. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090792