Grief Intervention in Suicide Loss Survivors through Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Impact of Suicide: Addressing Complicated Grief in Survivors

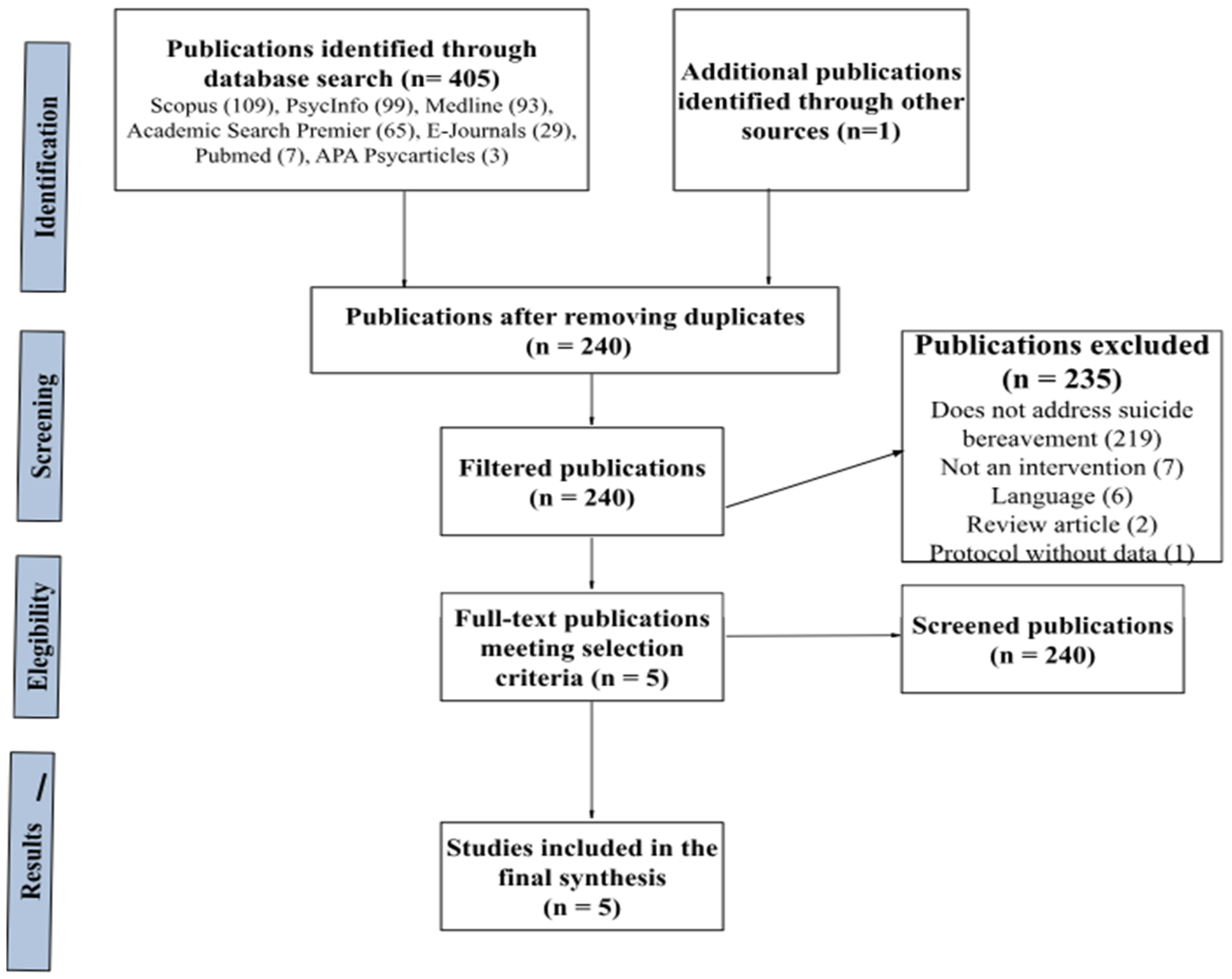

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

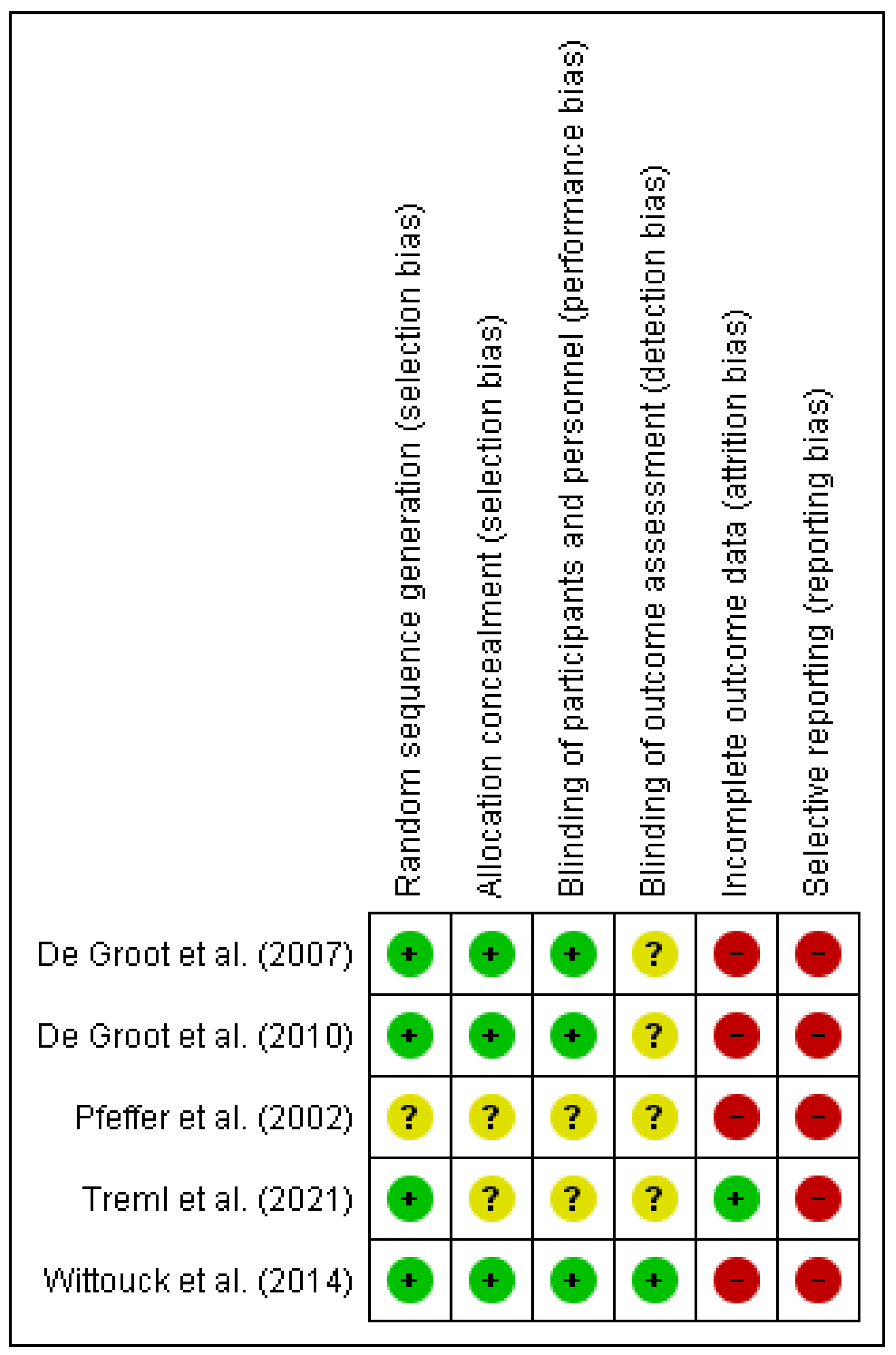

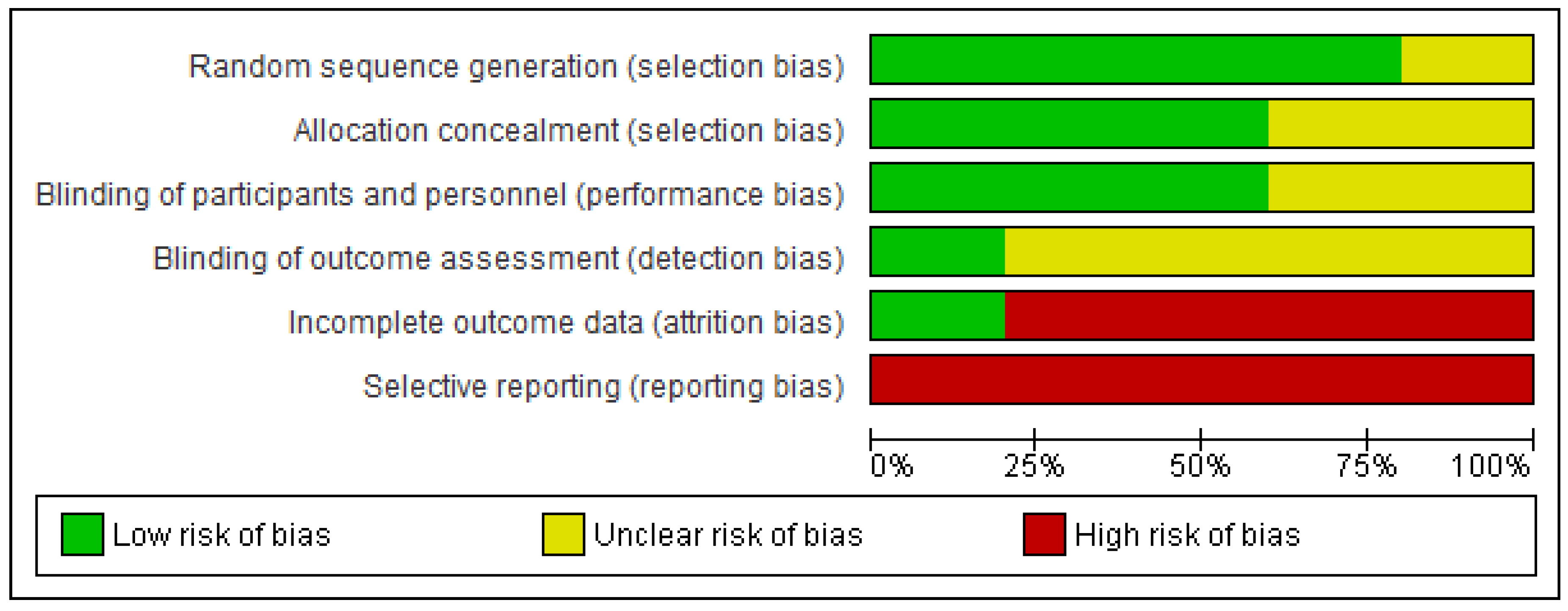

3.1. Methodological Quality Assessment

3.2. Participant Description

3.3. Description of Interventions

3.4. Intervention Effectiveness

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Linde, K.; Treml, J.; Steinig, J.; Nagl, M.; Kersting, A. Grief interventions for people bereaved by suicide: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naghavi, M. Global, regional, and national burden of suicide mortality 1990 to 2016: Systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. BMJ 2019, 364, l94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Suicide Worldwide in 2019: Global Health Estimates. Organización Mundial de la Salud, 2021. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/341728/9789240026643-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Facts About Suicide|Suicide Prevention. 25 April 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/facts (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Cerel, J.; Maple, M.; Aldrich, R.; van de Venne, J. Exposure to suicide and identification as survivor. Crisis 2013, 34, 413–419. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Judy-Van-De-Venne/publication/250922980_Exposure_to_Suicide_and_Identification_as_Survivor/links/5697d08c08aea2d74375c733/Exposure-to-Suicide-and-Identification-as-Survivor.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, F. Exploring the complexities of suicide bereavement research. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 165, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, J.R. Bereavement after suicide. Psychiatr. Ann. 2008, 38, 679–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shear, M.K.; Ghesquiere, A.; Katzke, M. Bereavement and complicated grief in older adults. Late Life Mood Disord. 2013, 14, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boelen, P.A.; Van Den Hout, M.A.; Van Den Bout, J. A cognitive-behavioral conceptualization of complicated grief. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2006, 13, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, A.; Gfroerer, J.; Han, B.; Ortega, L.; Parks, S.E. Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors among Adults Aged >18 Years—United States, 2008–2009; US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2011.

- Nizama, M. Suicidio. Rev. Peru. Epidemiol. 2011, 15, 1–5. Available online: https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/pt/biblio-1111629 (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Castillo, A.E. Contención del suicidio en España: Evaluación del diseño de las políticas y Planes de Salud Mental de las Comunidades Autónomas. Gest. Anál Polít Públicas 2022, 28, 6–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, K.L.; Conwell, Y.; Caine, E.D. If suicide is a public health problem, what are we doing to prevent it? Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raschke, N.; Mohsenpour, A.; Aschentrup, L.; Fischer, F.; Wrona, K.J. Socioeconomic factors associated with suicidal behaviors in South Korea: Systematic review on the current state of evidence. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zalsman, G. Suicide: Epidemiology, etiology, treatment and prevention. Harefuah 2019, 158, 468–472. Available online: https://europepmc.org/ (accessed on 20 April 2024). [PubMed]

- Andriessen, K. Can Postvention Be Prevention? Crisis 2009, 30, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, A.L. Estimating the population of survivors of suicide: Seeking an evidence base: Estimating the population of survivors of suicide. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2011, 41, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enez, Ö. Complicated Grief: Epidemiology, Clinical Features, Assessment, and Diagnosis. Psikiyatride Güncel Yaklaşımlar 2018, 10, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, I. Suicide Bereavement and Complicated Grief: Experiential Avoidance as a Mediating Mechanism. J. Loss Trauma 2016, 21, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, B.; Knaevelsrud, C.; Maercker, A. Internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for complicated grief: A randomized controlled trial. Death Stud. 2006, 30, 429–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, J.R.; McMenamy, J. Interventions for suicide survivors: A review of the literature. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2004, 34, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriessen, K.; Krysinska, K.; Hill, N.T.M.; Reifels, L.; Robinson, J.; Reavley, N.; Pirkis, J. Effectiveness of interventions for people bereaved through suicide: A systematic review of controlled studies of grief, psychosocial and suicide-related outcomes. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. Declaración PRISMA 2020: Una guía actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2021, 74, 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Green, S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Version 5.1.0). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available online: www.handbook.cochrane.org (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Pfeffer, C.R.; Jiang, H.; Kakuma, T.; Hwang, J.; Metsch, M. Group intervention for children bereaved by the suicide of a relative. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2002, 41, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, M.; de Keijser, J.; Neeleman, J.; Kerkhof, A.; Nolen, W.; Burger, H. Cognitive behaviour therapy to prevent complicated grief among relatives and spouses bereaved by suicide: Cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2007, 334, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, M.; Neeleman, J.; van der Meer, K.; Burger, H. The effectiveness of family-based cognitive-behavior grief therapy to prevent complicated grief in relatives of suicide victims: The mediating role of suicide ideation. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2010, 40, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittouck, C.; Van Autreve, S.; Portzky, G.; van Heeringen, K. A CBT-based psychoeducational intervention for suicide survivors. Crisis 2014, 35, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treml, J.; Nagl, M.; Linde, K.; Kündiger, C.; Peterhänsel, C.; Kersting, A. Efficacy of an Internet-based cognitive-behavioural grief therapy for people bereaved by suicide: A randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2021, 12, 1926650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, T.M. Trans-affirmative narrative exposure therapy (TA-NET): A therapeutic approach for targeting minority stress, internalized stigma, and trauma reactions among gender diverse adults. Pract. Innov. 2020, 5, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. The Bowlby-Ainsworth attachment theory. Behav. Brain Sci. 1979, 2, 637–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ness, D.; Pfeffer, C.R. Sequelae of bereavement resulting from suicide. Am. J. Psychiatry 1990, 147, 279–285. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Cognitive theories of stress and the issue of circularity. In Dynamics of Stress: Physiological, Psychological, and Social Perspectives; Appley, M.H., Trumbull, R., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1986; pp. 63–80. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, A.; Marshall, A. The support needs and experiences of suicidally bereaved family and friends. Death Stud. 2010, 34, 625–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Moreno, J.C.; Cantero-García, M.; Huertes-del Arco, A.; Izquierdo-Sotorrío, E.; Rueda-Extremera, M.; González-Moreno, J. Grief Intervention in Suicide Loss Survivors through Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy: A Systematic Review [Internet]. Available online: https://osf.io/ja3w4 (accessed on 24 July 2024).

| Author and Year | Design | Intervention | Measurements | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pfeffer et al. [25] | A total of 75 children (Nexperimental = 39; Ncontrol = 36). Mean age = 10.5 years old, SD = 3.2; 28 men. Pre- and post-intervention measures | Experimental group: BGI × 10 weekly group sessions, 1.5 h per session. Two components: psychoeducation and support. Groups of two–five children, organized by age (6–9 years old; 10–12 years old; 13–15 years old). Control group: Waiting list. | CPTSRI for post-traumatic symptomatology, CDI for depressive symptomatology, RCMAS for anxious symptomatology, SAICA to assess social adjustment. | Between-group comparisons: Significantly greater reductions in anxiety symptoms (p < 0.009; d = 0.80) and depressive symptoms (p < 0.01; d = 0.70) were observed in the experimental group compared with the control group, with larger reductions observed in middle-aged children (11 years old) compared with younger (6 years old) and older (14 years old) children. No significant differences were found in post-traumatic symptomatology or social adjustment. Within-group comparisons: Significant reductions were observed in post-measure anxiety symptoms (p < 0.04) and depressive symptoms (p < 0.003) in the experimental group, with a non-significant reduction in post-traumatic symptomatology (p < 0.06). |

| De Groot et al. [26] | A total of 134 participants > 15 years old (Nexperimental = 74; Ncontrol = 60). Mean age = 43 years old, SD= 13.6; 40 men. Preintervention measures (2.5 months after the suicide) and post-intervention measures (13 months after the suicide). | Experimental group: CBT counseling × four sessions of 2 h each, one session every 2–3 weeks. Intervention for the entire family system. Components: Psychoeducation, emotional processing, effective interaction, and problem-solving. Based on the theory of Boelen et al. [9]. Control group: Waiting list. | ITG complicated grief, CESD depressive symptomatology, PSI suicidal ideation, responsibility for suicide feelings with ad hoc questionnaire, TRGR2L maladaptive grief reactions. | Between-group comparisons: No effect on complicated grief (p = 0.82), depression levels (p = 0.28), or the presence of suicidal ideation, but there was an effect on maladaptive grief reactions with a notable but not significant reduction (p = 0.056) and on guilt perception with a significant reduction (p = 0.01). No within-group comparisons either each group. |

| De Groot et al. [27] | A total of 134 participants > 15 years old (Nexperimental = 74; Ncontrol = 60). Mean age= 43 years old, SD= 13.6; 40 men. Preintervention measures (2.5 months after the suicide) and post-intervention measures (13 months after the suicide). | Experimental group: CBT counseling × four sessions of 2 h each, one session every 2–3 weeks. Intervention for the entire family system. Components: Psychoeducation, emotional processing, effective interaction, and problem-solving. Based on the theory of Boelen et al. [9]. Control group: Waiting list. | EPQ-RSS, neuroticism; perceived sense of control over one’s life; self-esteem with RSES; family history of suicide; subjective expectation of suicide index; responsibility for suicide feelings with ad hoc scales; complicated grief with ITG; depressive symptoms with CESD; suicidal ideation with PSI; maladaptive grief reactions with TRGR2L; anxiety and depression with SCAN 2.1 | Survivors with suicidal ideation had a higher history of anxiety (p < 0.05), depression (p < 0.01), suicidal behavior (p < 0.001), and neuroticism (p < 0.001) and lower self-esteem (p < 0.001) compared with survivors without suicidal ideation. No significant differences were found in the interaction between suicidal ideation and intervention factors on the variables of complicated grief (p = 0.33), depressive symptoms (p = 0.57), or guilt perception (p = 0.60). There was a significantly greater reduction in maladaptive grief reactions (p = 0.03) and suicidal behavior (p = 0.03) among relatives with suicidal ideation |

| Wittouck et al. [28] | A total of 83 adult participants (Nexperimental = 47; Ncontrol = 36). Mean age = 48.6 years old, SD = 13.3; 20 men. Measures pre- and post-intervention. Four additional visits during the intervention in the experimental group. | Experimental group: CBT × home sessions lasting 2 h each session. Components: Psychoeducation about suicide, grief, specific aspects of grief due to suicide, and coping with grief. Based on the theory of Boelen et al. [9]. Control group: Waiting list. | Maladaptive grief symptomatology with ITG, depressive symptomatology with BDI-II, hopelessness with BHS, negative cognitions related to grief distress with CGQ, maladaptive coping with UCL. | Reducción significativa en el grupo experimental en sintomatología desadaptativa de duelo (p = 0.021) y en sintomatología depresiva (p = 0.006), pero no en desesperanza (p = 0.231). Sin reducción en grupo control ni en sintomatología de duelo (p = 0.503), ni en sintomatología depresiva (p = 0.250) ni en desesperanza (p = 0.688). Sin reducción en ninguna de las dimensiones del GCQ ni en grupo experimental ni en control. Reducción significativa en grupo experimental en las dimensiones del UCL “apoyo social” (p = 0.002), “reacción pasiva” (p = 0.013) y “expresión emocional” (p = 0.004). |

| Treml et al. [29] | A total of 58 adults (Nexperimental = 30; Ncontrol = 29). Mean age = 44.57 years old, SD= 14.25; 8 men. Measures pre- and post-intervention and follow-up at 3, 6, and 12 months after completing the intervention. | Experimental group: Online CBT × psychoeducation about suicide and suicide grief + 10 writing tasks (narrative therapy). Three phases: Coping, cognitive restructuring, and social exchange. Control group: Waiting list. | Severity of grief symptomatology with ICG, grief reaction after loss by suicide with GEQ, depressive symptomatology with BDI-II, general psychopathology with BSI. | Significant reductions in the follow-up measure at 12 months with respect to the post-measure in the experimental group versus the control in the GEQ subscales “guilt” (p = 0.043) and “shame” (p = 0.015), without differences among follow-up measures. No differences in follow-up in depressive symptoms or psychopathology in general. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Romero-Moreno, J.C.; Cantero-García, M.; Huertes-del Arco, A.; Izquierdo-Sotorrío, E.; Rueda-Extremera, M.; González-Moreno, J. Grief Intervention in Suicide Loss Survivors through Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy: A Systematic Review. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 791. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090791

Romero-Moreno JC, Cantero-García M, Huertes-del Arco A, Izquierdo-Sotorrío E, Rueda-Extremera M, González-Moreno J. Grief Intervention in Suicide Loss Survivors through Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy: A Systematic Review. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(9):791. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090791

Chicago/Turabian StyleRomero-Moreno, José Carlos, María Cantero-García, Ana Huertes-del Arco, Eva Izquierdo-Sotorrío, María Rueda-Extremera, and Jesús González-Moreno. 2024. "Grief Intervention in Suicide Loss Survivors through Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy: A Systematic Review" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 9: 791. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090791

APA StyleRomero-Moreno, J. C., Cantero-García, M., Huertes-del Arco, A., Izquierdo-Sotorrío, E., Rueda-Extremera, M., & González-Moreno, J. (2024). Grief Intervention in Suicide Loss Survivors through Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy: A Systematic Review. Behavioral Sciences, 14(9), 791. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090791