You Reap What You Sow: Customer Courtesy and Employees’ Prosocial Service Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

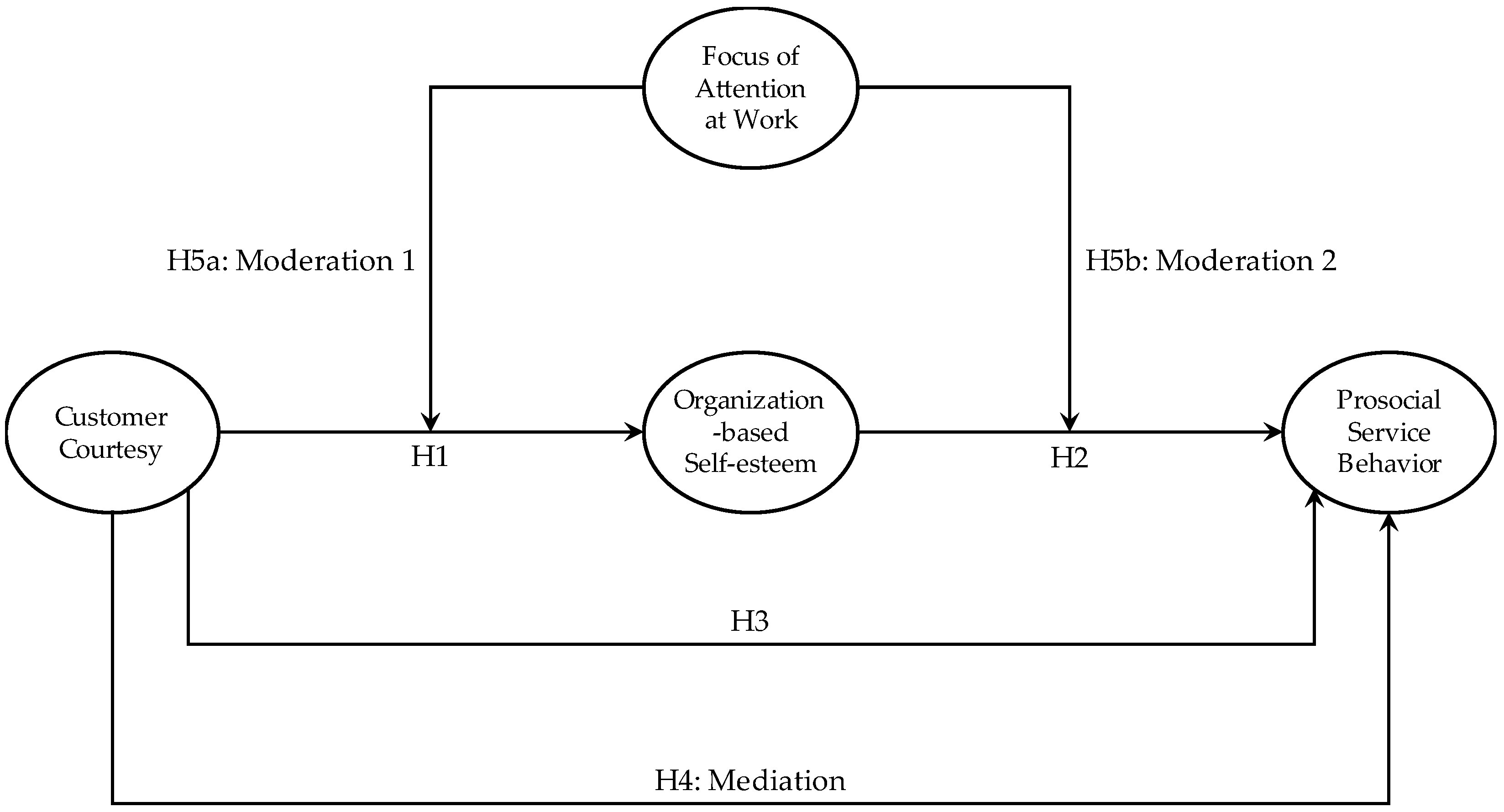

2. Hypotheses Development

2.1. Customer Courtesy and OBSE

2.2. OBSE and PSSB

2.3. Customer Courtesy and PSSB

2.4. Mediating Role of OBSE

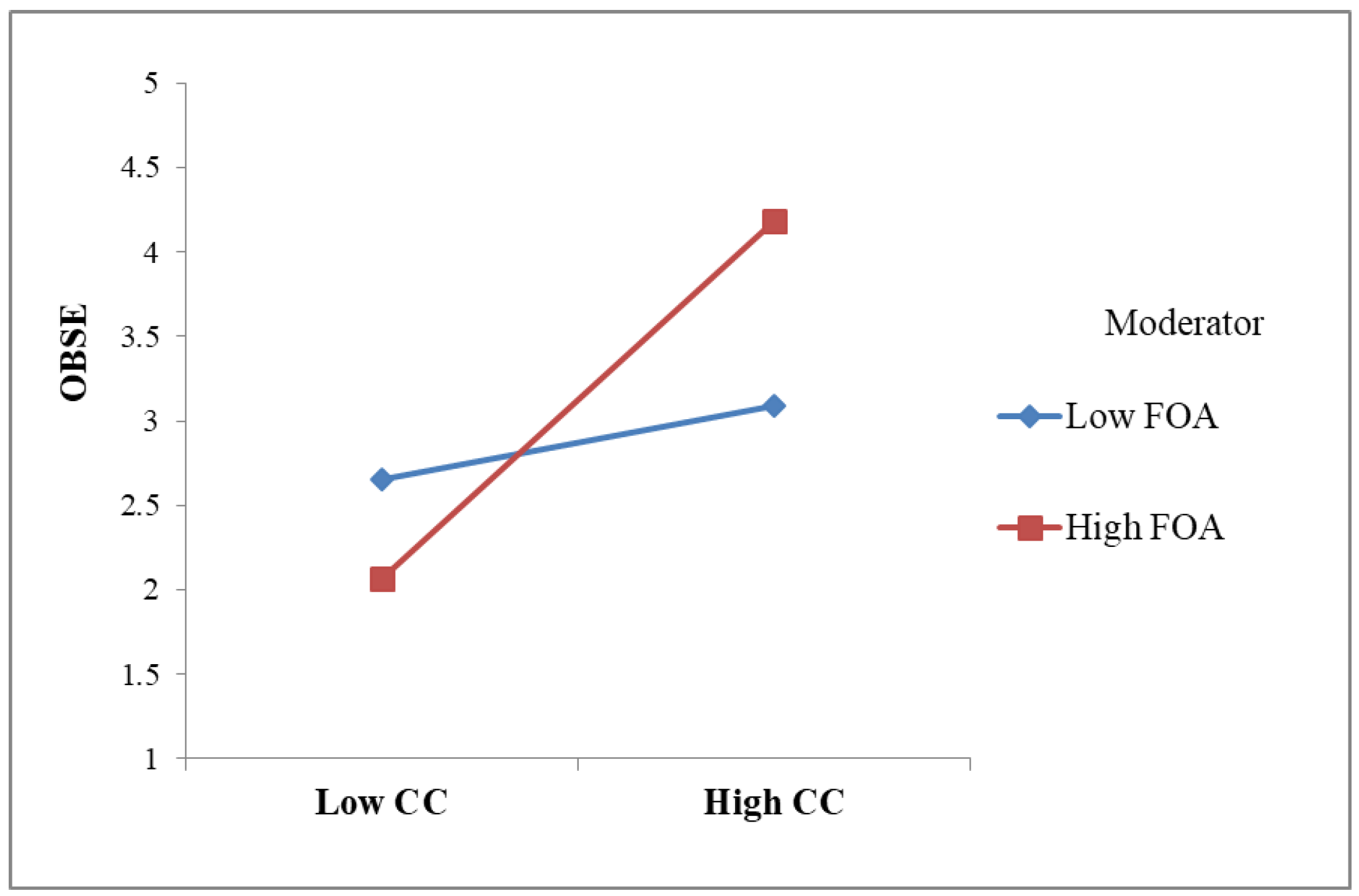

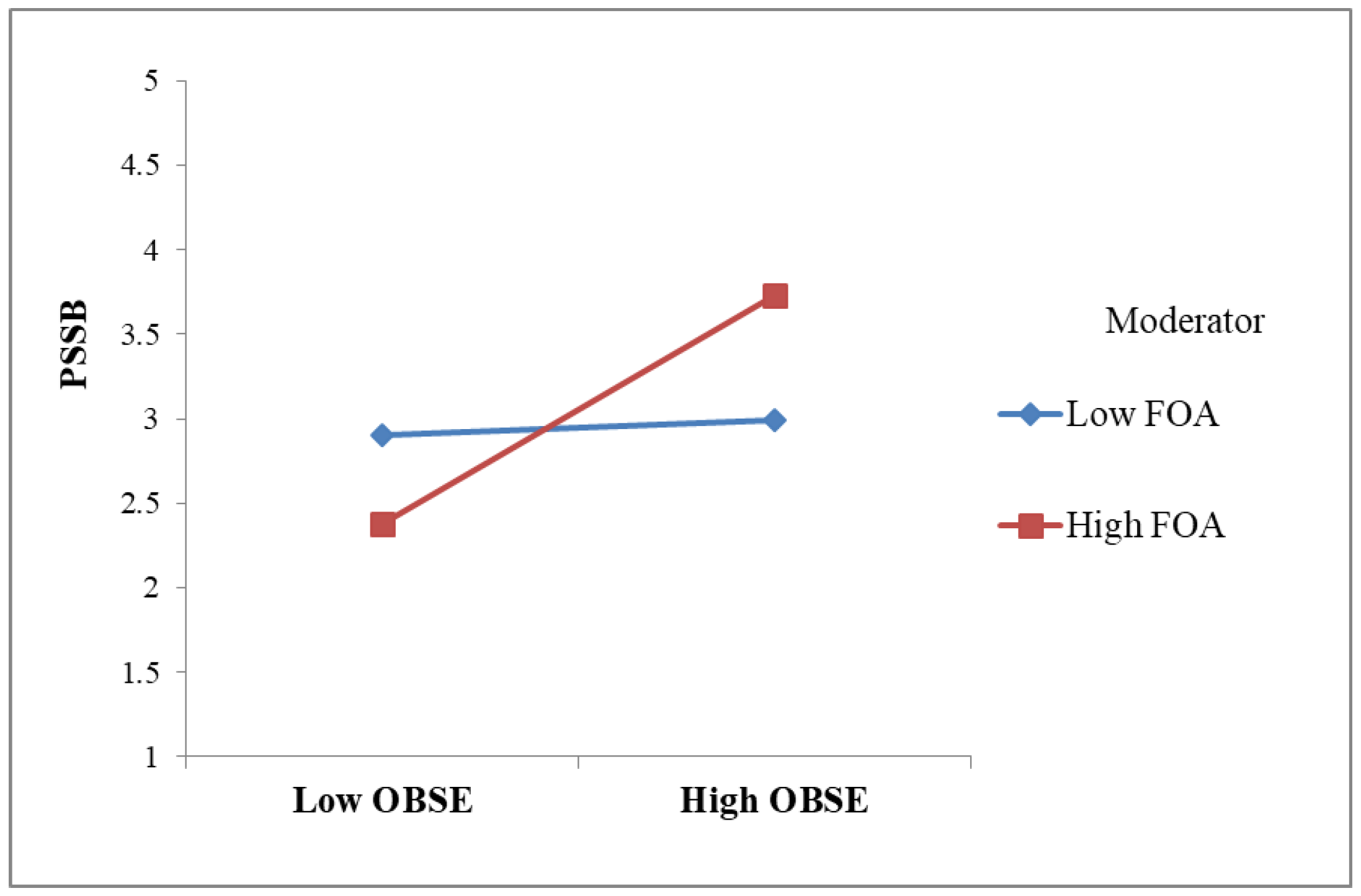

2.5. FAW as a Moderator

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Data Collection Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.3. Common Method Bias

3.4. Control Variables

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model Results

4.2. Structural Model Results

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lytle, R.S.; Timmerman, J.E. Service Orientation and Performance: An Organizational Perspective. J. Serv. Mark. 2006, 20, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B. The Climate for Service: An Application of the Climate Construct. In Organizational Climate and Culture; Schneider, B., Ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1990; pp. 383–412. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Y.; Huang, Q.; Wu, L.-Z.; Ye, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Miao, C. Why and When Perceived Organizational Exploitation Inhibits Frontline Hotel Employees’ Service Performance: A Social Exchange Approach. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2024. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochschild, A.R. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1983; ISBN 978-0-520-05454-7. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, J.-C.; Chen, C.-Y. Job Resourcefulness, Work Engagement and Prosocial Service Behaviors in the Hospitality Industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 2668–2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettencourt, L.A.; Brown, S.W. Contact Employees: Relationships among Workplace Fairness, Job Satisfaction and Prosocial Service Behaviors. J. Retail. 1997, 73, 39–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackfeldt, A.-L.; Wong, V. The Antecedents of Prosocial Service Behaviours: An Empirical Investigation. Serv. Ind. J. 2006, 26, 727–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, L.; Hwang, J. The Role of Prosocial and Proactive Personality in Customer Citizenship Behaviors. J. Consum. Mark. 2019, 36, 288–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.; Ackfeldt, A.-L. Internal Communication and Prosocial Service Behaviors of Front-Line Employees: Investigating Mediating Mechanisms. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4132–4139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.J.A.; Kim, W.G.; Choi, H.-M.; Li, Y. How to Fuel Employees’ Prosocial Behavior in the Hotel Service Encounter. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 84, 102333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Weng, Q.D.; Popelnukha, A.; Sungu, L.J. Their Bad Experiences Make Me Think Twice: Customer-to-Colleague Incivility, Self-Reflection, and Improved Service Delivery. Appl. Psychol. 2024, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmann, J.; Wang, M.; Liu, Y.; Song, Y. Customer Mistreatment: A Review of Conceptualizations and a Multilevel Theoretical Model. In Mistreatment in Organizations; Research in Occupational Stress and Well Being; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2015; Volume 13, pp. 33–79. ISBN 978-1-78560-117-0. [Google Scholar]

- Haldorai, K.; Kim, W.G.; Li, J.J. I’m broken inside but smiling outside: When does workplace ostracism promote pro-social behavior? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 101, 103088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaur, S.-H.; Wang, C.-H.; Yen, C.-H.; Liu, Y.-C. Job Standardization and Service Quality: The Mediating Role of Prosocial Service Behaviors. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 40, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, D.J.; Muir Zapata, C.P.; Yoon, M.H.; Kim, E. Customer Courtesy and Service Performance: The Roles of Self-Efficacy and Social Context. J. Organ. Behav. 2022, 43, 1015–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, J.L.; Gardner, D.G.; Cummings, L.L.; Dunham, R.B. Organization-Based Self-Esteem: Construct Definition, Measurement, And Validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1989, 32, 622–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, D.G.; Dunham, R.B.; Cummings, L.L.; Pierce, J.L. Focus of Attention at Work: Construct Definition and Empirical Validation. J. Occup. Psychol. 1989, 62, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramony, M.; Groth, M.; Hu, X.J.; Wu, Y. Four Decades of Frontline Service Employee Research: An Integrative Bibliometric Review. J. Serv. Res. 2021, 24, 230–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, J.G. Close to the Customer: But Is It Really a Relationship? J. Mark. Manag. 1994, 10, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.P.; Lam, S.K. A Meta-Analysis of Relationships Linking Employee Satisfaction to Customer Responses. J. Retail. 2008, 84, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Searcy, D.W. Positive Exchange Relationships With Customers. In Personal Relationships; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-0-203-12303-4. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, J.L.; Gardner, D.G. Self-Esteem Within the Work and Organizational Context: A Review of the Organization-Based Self-Esteem Literature. J. Manag. 2004, 30, 591–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockner, J. Self-Esteem at Work: Research, Theory, and Practice; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA, 1988; ISBN 978-0-669-09755-9. [Google Scholar]

- Korman, A.K. Toward an Hypothesis of Work Behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 1970, 54, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, D.G.; Huang, G.-H.E.; Pierce, J.L.; Niu, X.P.; Lee, C. Not Just for Newcomers: Organizational Socialization, Employee Adjustment and Experience, and Growth in Organization-Based Self-Esteem. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2022, 33, 297–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, D.E.; Schneider, B. Services Marketing and Management: Implications for Organizational Behavior. Res. Organ. Behav. 1988, 10, 43–80. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Kim, H.J. Customer Mistreatment and Service Performance: A Self-Consistency Perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 86, 102367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgunduz, Y.; Alkan, C.; Adan Gök, Ö. How Are the Exchange Relationships of Front Office Employees Reflected on Customers? Serv. Ind. J. 2022, 42, 798–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, L.; Burton, J.; Gruber, T. Developing a Deeper Understanding of Positive Customer Feedback. J. Serv. Mark. 2017, 32, 142–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouldner, A.W. The Norm of Reciprocity: A Preliminary Statement. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1960, 25, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarnani, R.K.; Bordia, P.; Restubog, S.L.D. Beyond Tit-for-Tat: Theorizing Divergent Employee Reactions to Customer Mistreatment. Group Organ. Manag. 2019, 44, 687–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker, J.; Wolfe, C.T. Contingencies of Self-Worth. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 108, 593–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Liao, H.; Chuang, A.; Zhou, J.; Campbell, E.M. Fostering Employee Service Creativity: Joint Effects of Customer Empowering Behaviors and Supervisory Empowering Leadership. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 1364–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinaityte, I.; Sacramento, C.; Aryee, S. Delighting the Customer: Creativity-Oriented High-Performance Work Systems, Frontline Employee Creative Performance, and Customer Satisfaction. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 728–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.; Wang, X.; Guchait, P. When Observers of Customer Incivility Revisit the Restaurant: Roles of Relationship Closeness and Norms. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 4227–4244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Liu, S.; Liao, H.; Gong, Y.; Kammeyer-Mueller, J.; Shi, J. Can’t Get It out of My Mind: Employee Rumination after Customer Mistreatment and Negative Mood in the next Morning. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 989–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilgen, D.R.; Fisher, C.D.; Taylor, M.S. Consequences of Individual Feedback on Behavior in Organizations. J. Appl. Psychol. 1979, 64, 349–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, D.G. The Importance of Being Resilient: Psychological Well-Being, Job Autonomy, and Self-Esteem of Organization Managers. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2020, 155, 109731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy Mechanism in Human Agency. Am. Psychol. 1982, 37, 122–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, D.D.; Marolla, J. Efficacious Action and Social Approval as Interacting Dimensions of Self-Esteem: A Tentative Formulation through Construct Validation. Sociometry 1976, 39, 324–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gecas, V.; Schwalbe, M.L. Beyond the Looking-Glass Self: Social Structure and Efficacy-Based Self-Esteem. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1983, 46, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, J.M.; Bettenhausen, K. Understanding Prosocial Behavior, Sales Performance, and Turnover: A Group-Level Analysis in a Service Context. J. Appl. Psychol. 1990, 75, 698–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Qu, H. The Mediating Roles of Gratitude and Obligation to Link Employees’ Social Exchange Relationships and Prosocial Behavior. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 644–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazer Winsted, K. Service Behaviors That Lead to Satisfied Customers. Eur. J. Mark. 2000, 34, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Chuang, A. A Multilevel Investigation of Factors Influencing Employee Service Performance and Customer Outcomes. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-J.; Kim, H.-S. The Impact of Hotel Customer Experience on Customer Satisfaction through Online Reviews. Sustainability 2022, 14, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovett, M.J.; Peres, R.; Shachar, R. On Brands and Word of Mouth. J. Mark. Res. 2013, 50, 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siguaw, J.A.; Mai, E.; Sheng, X. Word-of-Mouth, Servicescapes and the Impact on Brand Effects. SN Bus. Econ. 2020, 1, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Qin, M.; Zhou, W.; Wu, Y. Effect of Proactive Personality on Employees’ pro-Social Rule Breaking: The Role of Promotion Focus and Psychological Safety Climate. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 12768–12781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, B.; Cardona, P.; Ng, I.; Trau, R.N.C. Are Prosocially Motivated Employees More Committed to Their Organization? The Roles of Supervisors’ Prosocial Motivation and Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2017, 34, 951–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, A.M. Antecedents and Consequences of Employee Engagement Revisited. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2019, 6, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pincus, J.D. Employee Engagement as Human Motivation: Implications for Theory, Methods, and Practice. Integr. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 2023, 57, 1223–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truss, C.; Shantz, A.; Soane, E.; Alfes, K.; Delbridge, R. Employee Engagement, Organisational Performance and Individual Well-Being: Exploring the Evidence, Developing the Theory. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 2657–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clack, L. Employee Engagement: Keys to Organizational Success. In The Palgrave Handbook of Workplace Well-Being; Dhiman, S.K., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1001–1028. ISBN 978-3-030-30025-8. [Google Scholar]

- Korman, A.K. Organizational Achievement, Aggression and Creativity: Some Suggestions toward an Integrated Theory. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1971, 6, 593–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, D.G.; Pierce, J.L. Organization-Based Self-Esteem in Work Teams. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2016, 19, 394–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Song, H.; Li, H. Idiosyncratic Deals and Occupational Well-Being in the Hospitality Industry: The Mediating Role of Organization-Based Self-Esteem. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 3797–3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyne, L.; Vandewalle, D.; Kostova, T.; Latham, M.E.; Cummings, L.L. Collectivism, Propensity to Trust and Self-Esteem as Predictors of Organizational Citizenship in a Non-Work Setting. J. Organ. Behav. 2000, 21, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Beehr, T.A. Organization-Based Self-Esteem and Meaningful Work Mediate Effects of Empowering Leadership on Employee Behaviors and Well-Being. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2018, 25, 385–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaucher, B.; Chebat, J.-C. How Uncivil Customers Corrode the Relationship between Frontline Employees and Retailers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 46, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, F.Z. How Does Customer Cooperation Affect Employees’ Prosocial Service Behavior in Upscale Chinese Hotels? An Affective Social Exchange Perspective. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 2071–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettencourt, L.A. Customer Voluntary Performance: Customers as Partners in Service Delivery. J. Retail. 1997, 73, 383–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dolen, W.; de Ruyter, K.; Lemmink, J. An Empirical Assessment of the Influence of Customer Emotions and Contact Employee Performance on Encounter and Relationship Satisfaction. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.-H.; Gao, Y. Understanding Emotional Customer Experience and Co-Creation Behaviours in Luxury Hotels. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 4247–4275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social Exchange Theory: An Interdisciplinary Review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, E.J. An Affect Theory of Social Exchange. Am. J. Sociol. 2001, 107, 321–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Anthony, E.L.; Daniels, S.R.; Hall, A.V. Social Exchange Theory: A Critical Review with Theoretical Remedies. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 479–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadfar, H.; Brege, S.; Sarah Ebadzadeh Semnani, S. Customer Involvement in Service Production, Delivery and Quality: The Challenges and Opportunities. Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2013, 5, 46–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzoli, G.; Hancer, M.; Kim, B.P. Explaining Why Employee-customer Orientation Influences Customers’ Perceptions of the Service Encounter. J. Serv. Manag. 2013, 24, 382–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farh, J.-L.; Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Accounting for Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Leader Fairness and Task Scope versus Satisfaction. J. Manag. 1990, 16, 705–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, D.L.; Brown, D.J.; Lian, H.; Keeping, L.M. When Does Self-Esteem Relate to Deviant Behavior? The Role of Contingencies of Self-Worth. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1345–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, D.G.; Pierce, J.L. Focus of Attention at Work and Organization-based Self-esteem. J. Manag. Psychol. 2013, 28, 110–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorence, J.; Mortimer, J.T. Job Involvement through the Life Course: A Panel Study of Three Age Groups. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1985, 50, 618–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D. Attention and Effort; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1973; ISBN 978-0-13-050518-7. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, V.T.; Wong, S.-S.; Lee, C.H. A Tale of Passion: Linking Job Passion and Cognitive Engagement to Employee Work Performance. J. Manag. Stud. 2011, 48, 26–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, J.M.; Ho, V.T.; O’Boyle, E.H.; Kirkman, B.L. Passion at Work: A Meta-Analysis of Individual Work Outcomes. J. Organ. Behav. 2020, 41, 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegall, M.; McDonald, T. Implementing a Job Change: The Impact of Employee Focus of Attention. J. Manag. Psychol. 1996, 11, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, W.B.; Johnson, R.E.; Bosson, J.K. Identity Negotiation at Work. Res. Organ. Behav. 2009, 29, 81–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, N.A.; Eschleman, K.J.; Wang, Q.; Kirkendall, C.; Alarcon, G. A Meta-Analysis of the Predictors and Consequences of Organization-Based Self-Esteem. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 601–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Podsakoff, N.P.; Williams, L.J.; Huang, C.; Yang, J. Common Method Bias: It’s Bad, It’s Complex, It’s Widespread, and It’s Not Easy to Fix. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2024, 11, 17–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, M.K.; Whitney, D.J. Accounting for Common Method Variance in Cross-Sectional Research Designs. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common Method Bias in PLS-SEM: A Full Collinearity Assessment Approach. Int. J. E-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS 4; SmartPLS: Bönningstedt, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-4833-7741-4. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS Procedures for Estimating Indirect Effects in Simple Mediation Models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.A.; Kim, K. Other Customer Service Failures: Emotions, Impacts, and Attributions. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2018, 42, 1067–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bipp, T.; Kleingeld, A.; Ebert, T. Core Self-Evaluations as a Personal Resource at Work for Motivation and Health. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2019, 151, 109556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Guo, G.; Tian, J.; Shaalan, A. Customer Incivility and Service Sabotage in the Hotel Industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 1737–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.J.; Bonn, M.A.; Cho, M. The Relationship between Customer Incivility, Restaurant Frontline Service Employee Burnout and Turnover Intention. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 52, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.-D.; Liu, Y.-C.; Zhuang, W.-L.; Wang, C.-H. Using Social Exchange Perspective to Explain Customer Voluntary Performance Behavior. Serv. Ind. J. 2023, 43, 764–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-Y.D.; Wu, S.-H.; Huang, S.C.-T. From Mandatory to Voluntary: Consumer Cooperation and Citizenship Behaviour. Serv. Ind. J. 2017, 37, 521–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zablah, A.R.; Sirianni, N.J.; Korschun, D.; Gremler, D.D.; Beatty, S.E. Emotional Convergence in Service Relationships: The Shared Frontline Experience of Customers and Employees. J. Serv. Res. 2017, 20, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogreve, J.; Iseke, A.; Derfuss, K.; Eller, T. The Service–Profit Chain: A Meta-Analytic Test of a Comprehensive Theoretical Framework. J. Mark. 2017, 81, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solnet, D.; Ford, R.; McLennan, C.-L. What Matters Most in the Service-Profit Chain? An Empirical Test in a Restaurant Company. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 260–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, R.; Skarlicki, D.P. Service Employees’ Reactions to Mistreatment by Customers: A Comparison Between North America and East Asia. Pers. Psychol. 2014, 67, 23–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rentzsch, K.; Schröder–Abé, M. Stability and Change in Domain–Specific Self–Esteem and Global Self–Esteem. Eur. J. Personal. 2018, 32, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, D.C.; Ponder, N.; Hopkins, C.D. The Impact of Perceived Customer Delight on the Frontline Employee. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.J.; Zhu, T.T.; Loi, R.; Chow, C.W.C. Can Customer Participation Promote Hospitality Frontline Employees’ Extra-Role Service Behavior? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 35, 218–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-P.; Lai, C.-F. Does a Leader’s Motivating Language Enhance the Customer-Oriented Prosocial Behavior of Frontline Service Employees? Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2024, 29, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Cheng, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y. Role Stress and Prosocial Service Behavior of Hotel Employees: A Moderated Mediation Model of Job Satisfaction and Social Support. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 698027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth, M.; Wu, Y.; Nguyen, H.; Johnson, A. The Moment of Truth: A Review, Synthesis, and Research Agenda for the Customer Service Experience. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2019, 6, 89–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.; Jang, J.; Roberts, K.R. Are Employees with Higher Organization-Based Self-Esteem Less Likely to Quit? A Moderated Mediation Model. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 73, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, D.E.; Lohse, K.R.; Healy, A.F. The Effect of an External and Internal Focus of Attention on Dual-Task Performance. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 2020, 46, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Choi, L.; Knutson, B.J.; Borchgrevink, C.P. Hotel Employees’ Organizational Behaviors from Cross-National Perspectives. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 3082–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, E.; Wang, Y.-C.; Qu, H. Reenergizing Through Angel Customers: Cross-Cultural Validation of Customer-Driven Employee Citizenship Behavior. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2022, 63, 334–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, H.M.; Beal, D.J. Reflections on Affective Events Theory. In The Effect of Affect in Organizational Settings; Ashkanasy, M.N., Zerbe, W.J., Härtel, C.E.J., Eds.; Research on Emotion in Organizations; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2005; Volume 1, pp. 1–21. ISBN 978-0-7623-1234-4. [Google Scholar]

| Constructs and Items | Loadings | Cronbach’s α | Composite Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Customer courtesy | 0.816 | 0.872 | 0.578 | |

| “My customers usually act courteously to me.” | 0.667 | |||

| “My customers are cooperative with me so that I can serve them easily.” | 0.755 | |||

| “My customers are well-mannered.” | 0.798 | |||

| “My customers usually treat me with warmth.” | 0.835 | |||

| “My customers like me as a service employee.” | 0.734 | |||

| Organization-based self-esteem | 0.933 | 0.944 | 0.629 | |

| “I count around here.” | 0.845 | |||

| “I am taken seriously around here.” | 0.853 | |||

| “I am important around here.” | 0.855 | |||

| “I am trusted around here.” | 0.793 | |||

| “There is faith in me around here.” | 0.814 | |||

| “I can make a difference around here.” | 0.877 | |||

| “I am valuable around here.” | 0.810 | |||

| “I am helpful around here.” | 0.758 | |||

| “I am efficient around here.” | 0.646 | |||

| “I am cooperative around here.” | 0.642 | |||

| Prosocial service behavior | 0.913 | 0.936 | 0.744 | |

| “Voluntarily assists customers even if it means going beyond job requirements.” | 0.750 | |||

| “Helps customers with problems beyond what is expected or required.” | 0.905 | |||

| “Often goes above and beyond the call of duty when serving customers.” | 0.886 | |||

| “Willingly goes out of his/her way to make a customer satisfied.” | 0.898 | |||

| “Frequently goes out the way to help a customer.” | 0.865 | |||

| Focus of attention at work | 0.801 | 0.879 | 0.709 | |

| “How often you think about job factors while at work.” | 0.869 | |||

| “How often you think about work unit factors while at work.” | 0.893 | |||

| “How often you think about off-the-job factors while at work.” | 0.761 |

| CC | OBSE | PSSB | FOA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Customer courtesy | 0.760 | |||

| Organization-based self-esteem | 0.636 | 0.793 | ||

| Prosocial service behavior | 0.661 | 0.635 | 0.863 | |

| Focus of attention at work | 0.173 | 0.353 | 0.297 | 0.842 |

| Paths | Path Coefficient | t-Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Customer courtesy → OBSE | 0.637 | 20.137 ** | Supported |

| H2: OBSE → PSSB | 0.359 | 8.117 ** | Supported |

| H3: Customer courtesy → PSSB | 0.432 | 10.746 ** | Supported |

| H4: Customer courtesy → OBSE → PSSB | 0.227 | CI [0.168, 0.293] | Supported |

| H5a: Customer courtesy × FAW → OBSE | 0.420 | 5.092 ** | Supported |

| H5b: OBSE × FAW → PSSB | 0.316 | 3.359 ** | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pan, C.; Choi, H.-M. You Reap What You Sow: Customer Courtesy and Employees’ Prosocial Service Behavior. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 736. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090736

Pan C, Choi H-M. You Reap What You Sow: Customer Courtesy and Employees’ Prosocial Service Behavior. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(9):736. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090736

Chicago/Turabian StylePan, Cuicui, and Hyung-Min Choi. 2024. "You Reap What You Sow: Customer Courtesy and Employees’ Prosocial Service Behavior" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 9: 736. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090736

APA StylePan, C., & Choi, H.-M. (2024). You Reap What You Sow: Customer Courtesy and Employees’ Prosocial Service Behavior. Behavioral Sciences, 14(9), 736. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090736