Factors Influencing Intentions of People with Hearing Impairments to Use Augmented Reality Glasses as Hearing Aids

Abstract

1. Introduction

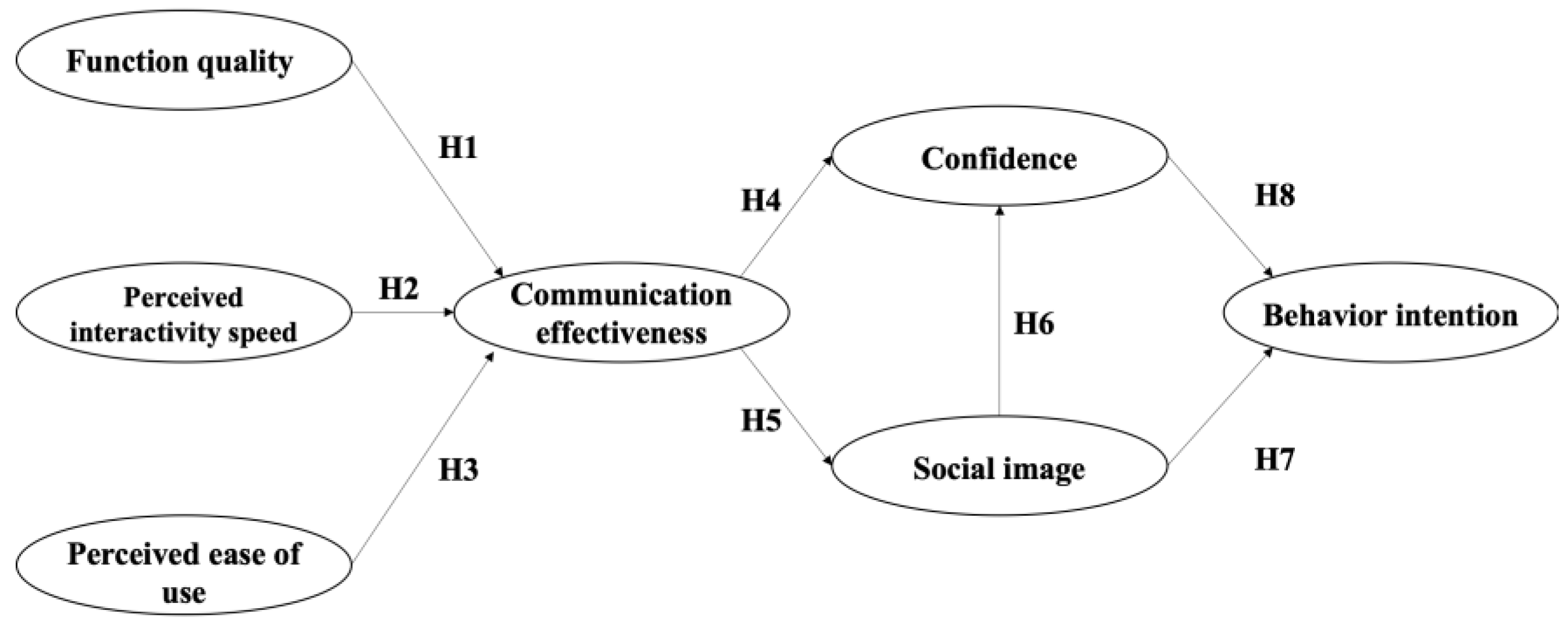

2. Theoretical Framework and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Function Quality

2.2. Perceived Interaction Speed

2.3. Perceived Ease of Use

2.4. Communication Effectiveness

2.5. Social Image

2.6. Confidence

3. Questionnaire Design and Data Collection

3.1. Questionnaire Design

3.2. Data Collection

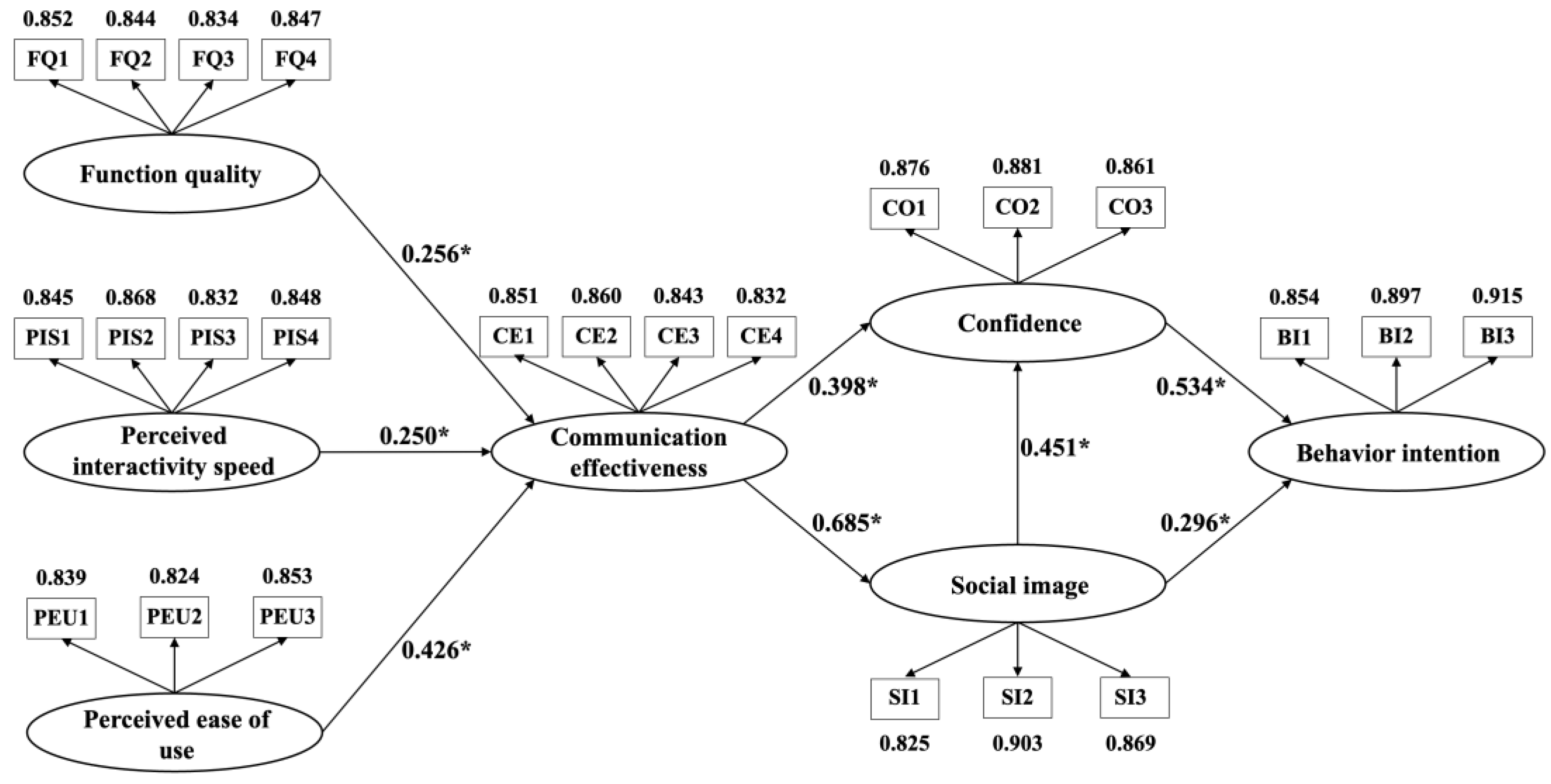

4. Data Analysis and Results

5. Discussion

6. Contributions and Limitations

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

- (1).

- This study enriches the field of behavioral research in hearing impairment and design. By introducing sociotechnical systems theory into the study of hearing impairment behavior, it explores how the interaction between technological, social, and individual dimensions affects the experience of PHI using AR hearing aid glasses, thereby influencing their subsequent adoption intentions. This research provides a new explanatory pathway for the behavior of PHI using AR hearing glasses and offers a theoretical framework for further understanding and recognizing the deep needs of PHI. It also provides theoretical support for the development and design of hearing impairment treatments, services, and related products. Furthermore, this study helps overcome the limitations of technocentrism and partial perspectives in hearing impairment research.

- (2).

- Through quantitative analysis, this study elucidates the intrinsic mechanisms and decision-making pathways for PHI choosing AR glasses as hearing aid devices. Specifically, it identifies that social image and confidence are the decisive factors influencing users’ intention to use AR hearing aid glasses, while the technical aspects of functional quality, perceived interactivity speed, and perceived ease of use are merely necessary prerequisites and foundations and do not directly determine the intention to use AR hearing aid glasses. This finding aligns with the general direction of existing research on hearing impairment and hearing aid technology, providing further empirical evidence. Additionally, by examining specific aspects and more tangible product targets, this study clarifies the intrinsic relationships and influencing mechanisms between variables at the technical, social, and individual levels and the intention to use AR hearing glasses. This provides more targeted theoretical guidance for strategy formulation and practical implementation in the field of hearing aid technology and services.

6.2. Practical Contributions

- (1).

- In the development of AR hearing-assistive glasses, special attention should be given to the interactive ease-of-use design of the AR glasses. The basic operations of the AR glasses should be simplified to prevent users from abandoning their use due to difficulty. Consideration can even be given to employing the most advanced intelligent proactive interactive methods, allowing for the device to autonomously complete interactions based on circumstances. This avoids tedious operations during communication and allows for users to focus on communicating, thereby enhancing the communication experience.

- (2).

- It is essential to integrate as many functions as possible, such as noise reduction, multi-directional microphone pickups, and adaptive light brightness adjustments and ensure the high quality of these features to assist PHI in communicating normally in various environments. It is also vital to improve the interaction speed of AR hearing-assistive glasses, such as the response speed for keyword activation and the speed of voice-to-text, so that PHI can maintain a consistent rhythm with their counterparts during communication.

- (3).

- The design of AR glasses should closely resemble regular glasses used in daily life. The lens can adopt a single-sided design to ensure the virtual interface is not visible to others, thus avoiding excessive attention. This helps PHI rid themselves of the “special” label, thereby building social confidence. It is also essential to design the text information’s display size, color, transparency, and position well, so users can clearly view the text while not obscuring the eyes and non-verbal actions of others. This facilitates more eye contact during communication, allowing for users to express their sincerity, earn the respect of others, establish a positive social image, and better integrate into various aspects of life, education, and work.

6.3. Research Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roizen, N.J. Nongenetic causes of hearing loss. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2003, 9, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniel, E. Noise and Hearing Loss: A Review. J. Sch. Health 2007, 77, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willems, P.J. Genetic Causes of Hearing Loss. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 342, 1101–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonelli, M.; Warick, R. Focusing on the Needs of People with Hearing Loss During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond. JAMA 2022, 327, 1129–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Min, C.; Yoo, D.M.; Chang, J.; Lee, H.-J.; Park, B.; Choi, H.G. Hearing Impairment Increases Economic Inequality. Clin. Exp. Otorhinolaryngol. 2021, 14, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. World Report on Hearing: Executive Summary; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Swanepoel, W.; De Sousa, K.C.; Smits, C.; Moore, D.R. Mobile applications to detect hearing impairment: Opportunities and challenges. Bull. World Health Organ. 2019, 97, 717–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, L.; Wang, B.; Zhang, J.; Yin, L.; Pu, Y. A functional SNP in miR-625-5p binding site of AKT2 3′UTR is associated with noise-induced hearing loss susceptibility in the Chinese population. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 40782–40792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olusanya, B.O.; Davis, A.C.; Hoffman, H.J. Hearing loss: Rising prevalence and impact. Bull. World Health Organ. 2019, 97, 646–646a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, A.; Harper, M.; Pedersen, E.; Goman, A.; Suen, J.J.; Price, C.; Applebaum, J.; Hoyer, M.; Lin, F.R.; Reed, N.S. Hearing Loss, Loneliness, and Social Isolation: A Systematic Review. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2020, 162, 622–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlenforst, B.; Zekveld, A.A.; Jansma, E.P.; Wang, Y.; Naylor, G.; Lorens, A.; Lunner, T.; Kramer, S.E. Effects of hearing impairment and hearing aid amplification on listening effort: A systematic review. Ear Hear. 2017, 38, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Deafness and Hearing Loss. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/deafness-and-hearing-loss (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Sawyer, C.S.; Armitage, C.J.; Munro, K.J.; Singh, G.; Dawes, P.D. Correlates of hearing aid use in UK adults: Self-reported hearing difficulties, social participation, living situation, health, and demographics. Ear Hear. 2019, 40, 1061–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takaki, K.; Nozaki, E.; Kanai, T.; Hautasaari, A.; Kashio, A.; Sato, D.; Kamogashira, T.; Uranaka, T.; Urata, S.; Koyama, H. asEars: Designing and Evaluating the User Experience of Wearable Assistive Devices for Single-Sided Deafness. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New York, NY, USA, 23–28 April 2023; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kawata, N.; Nouchi, R.; Oba, K.; Matsuzaki, Y.; Kawashima, R. Auditory cognitive training improves brain plasticity in healthy older adults: Evidence from a randomized controlled trial. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, S.S.; Supena, A.; Yatimah, D. Utilization of Internet Media by Deaf Persons for Language Learning (Case study on 11-year-old child at SLB B Tunas Kasih 2, Bogor City, West Java). In Proceedings of the International Conference on Education, Science and Technology, West Sumatera, Indonesia, 13–16 March 2019; pp. 151–157. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, S.-H.; Jeong, S.W.; Kim, L.-S. A case of auditory neuropathy caused by pontine hemorrhage in an adult. J. Audiol. Otol. 2017, 21, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wu, H.C.; Thallmayer, T.; Deal, J.A.; Betz, J.F.; Reed, N.S.; Lin, F.R. Prevalence Trends in Hearing Aid Use among US Adults Aged 50 to 69 Years with Hearing Loss—2011 to 2016 vs. 1999 to 2004. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2021, 147, 831–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, J.-P.; Southall, K.; Jennings, M.B. Stigma and self-stigma associated with acquired hearing loss in adults. Hear. Rev. 2011, 18, 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- KochKiN, S. MarkeTrak VIII: The key influencing factors in hearing aid purchase intent. Hear. Rev. 2012, 19, 12–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kochkin, S. MarkeTrak VII: Obstacles to adult non-user adoption of hearing aids. Hear. J. 2007, 60, 24–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenstad, L.; Moon, J. Systematic review of barriers and facilitators to hearing aid uptake in older adults. Audiol. Res. 2011, 1, e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meister, H.; Walger, M.; Brehmer, D.; von Wedel, U.-C.; von Wedel, H. The relationship between pre-fitting expectations and willingness to use hearing aids. Int. J. Audiol. 2008, 47, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, D.; Werner, P. Stigma regarding hearing loss and hearing aids: A scoping review. Stigma Health 2016, 1, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southall, K.; Gagné, J.-P.; Jennings, M.B. Stigma: A negative and a positive influence on help-seeking for adults with acquired hearing loss. Int. J. Audiol. 2010, 49, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruusuvuori, J.E.; Aaltonen, T.; Koskela, I.; Ranta, J.; Lonka, E.; Salmenlinna, I.; Laakso, M. Studies on stigma regarding hearing impairment and hearing aid use among adults of working age: A scoping review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2021, 43, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Li, J. Design of an AR Realistic Interactive Hearing Aid System Based on Digital Construction. Packag. Eng. 2023, 44, 404–410. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehra, R.; Brimijoin, O.; Robinson, P.; Lunner, T. Potential of Augmented Reality Platforms to Improve Individual Hearing Aids and to Support More Ecologically Valid Research. Ear Hear. 2020, 41, 140s–146s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridha, A.M.; Shehieb, W. Assistive technology for hearing-impaired and deaf students utilizing augmented reality. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Canadian Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering (CCECE), Virtual, 12–17 September 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Amlani, A.M.; Taylor, B.; Levy, C.; Robbins, R. Utility of smartphone-based hearing aid applications as a substitute to traditional hearing aids. Hear. Rev. 2013, 20, 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Slaney, M.; Lyon, R.F.; Garcia, R.; Kemler, B.; Gnegy, C.; Wilson, K.; Kanevsky, D.; Savla, S.; Cerf, V.G. Auditory measures for the next billion users. Ear Hear. 2020, 41, 131S–139S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochsner, B.; Spöhrer, M.; Stock, R. Rethinking assistive technologies: Users, environments, digital media, and app-practices of hearing. NanoEthics 2022, 16, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, A.D.P.; Ferrari, A.L.M.; Medola, F.O.; Sandnes, F.E. Aesthetics and the perceived stigma of assistive technology for visual impairment. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2022, 17, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufraux, A.; Vincent, E.; Hannun, A.; Brun, A.; Douze, M. Lead2Gold: Towards exploiting the full potential of noisy transcriptions for speech recognition. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Automatic Speech Recognition and Understanding Workshop (ASRU), Singapore, 14–18 December 2019; pp. 78–85. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, P.F.; Tucker, R.V. Assistive Communication Technologies and Stigma: How Perceived Visibility of Cochlear Implants Affects Self-Stigma and Social Interaction Anxiety. Proc. ACM Hum. Comput. Interact. 2022, 6, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, V.; Wang, Y.; Wills, G. Research investigations on the use or non-use of hearing aids in the smart cities. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 153, 119231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desjardins, J.L.; Sotelo, L.R. Self-Reported Reasons for the Non-Use of Hearing Aids among Hispanic Adults with Hearing Loss. Am. J. Audiol. 2021, 30, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawyer, C.S.; Munro, K.J.; Dawes, P.; O’Driscoll, M.P.; Armitage, C.J. Beyond motivation: Identifying targets for intervention to increase hearing aid use in adults. Int. J. Audiol. 2019, 58, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, K.; Pullin, G. Uncovering Nuance: Exploring Hearing Aids and Super Normal Design. Des. J. 2019, 22, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, A.; Constantinou, V. Augmented reality supporting deaf students in mainstream schools: Two case studies of practical utility of the technology. In Interactive Mobile Communication Technologies and Learning: Proceedings of the 11th IMCL Conference; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 387–396. [Google Scholar]

- Federici, S.; Meloni, F.; Borsci, S. The abandonment of assistive technology in Italy: A survey of users of the national health service. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2016, 52, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Petrie, H.; Carmien, S.; Lewis, A. Assistive technology abandonment: Research realities and potentials. In Computers Helping People with Special Needs: 16th International Conference, ICCHP 2018, Linz, Austria, 11–13 July 2018, Proceedings, Part II 16; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 532–540. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.E.; Ma, S.M.; Park, H.; Cho, Y.-S.; Hong, S.H.; Moon, I.J. A comparison between wireless CROS/BiCROS and soft-band BAHA for patients with unilateral hearing loss. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jonge, D.; Aplin, T.; Larkin, S.; Ainsworth, E. The aesthetic appeal of assistive technology and the economic value baby boomers place on it: A pilot study. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2016, 63, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trist, E.L. The Evolution of Socio-Technical Systems; Ontario Quality of Working Life Centre: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1981; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- van Eijnatten, F.M. Developments in socio-technical systems design (STSD). In A Handbook of Work and Organizational Psychology; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2013; pp. 61–88. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, M. Socio-technical systems and interaction design—21st century relevance. Appl. Ergon. 2014, 45, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sony, M.; Naik, S. Industry 4.0 integration with socio-technical systems theory: A systematic review and proposed theoretical model. Technol. Soc. 2020, 61, 101248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punch, J.L.; Hitt, R.; Smith, S.W. Hearing loss and quality of life. J. Commun. Disord. 2019, 78, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.M.; Chuan-Chuan Lin, J. The effect of social influence on bloggers’ usage intention. Online Inf. Rev. 2011, 35, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steuer, J.; Biocca, F.; Levy, M.R. Defining virtual reality: Dimensions determining telepresence. Commun. Age Virtual Real. 1995, 33, 37–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. New Measures for Three User Acceptance Constructs: Attitude Toward Using, Perceived Usefulness, and Perceived Ease of Use. Student Thesis, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney, A.D.; Morrison, M.D.; Jarratt, D.; Heffernan, T. Modeling the constructs contributing to the effectiveness of marketing lecturers. J. Mark. Educ. 2009, 31, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.P.; Bhattacherjee, A. Extending technology usage models to interactive hedonic technologies: A theoretical model and empirical test. Inf. Syst. J. 2010, 20, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkes, R.E. A structural modeling approach to the measurement and meaning of cognitive age. J. Consum. Res. 1992, 19, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Todd, P.A. Understanding information technology usage: A test of competing models. Inf. Syst. Res. 1995, 6, 144–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, K.; Iqbal, M.N.; Mushtaq, R.; Shakeel, M. Effectiveness of Assistive Technology in Teaching Mathematics to the Students with Hearing Impairment at Primary Level. VFAST Trans. Educ. Soc. Sci. 2022, 10, 93–99. [Google Scholar]

- Bambacas, M.; Patrickson, M. Interpersonal communication skills that enhance organisational commitment. J. Commun. Manag. 2008, 12, 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gugenheimer, J.; Plaumann, K.; Schaub, F.; Vito, P.D.C.S.; Duck, S.; Rabus, M.; Rukzio, E. The Impact of Assistive Technology on Communication Quality Between Deaf and Hearing Individuals. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing, Portland, OR, USA, 25 February–1 March 2017; pp. 669–682. [Google Scholar]

- Sockalingam, R.; Holmberg, M.; Eneroth, K.; Shulte, M. Binaural hearing aid communication shown to improve sound quality and localization. Hear. J. 2009, 62, 46–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, C.K.A.; Shankar, N.; Bhat, G.S.; Charan, R.; Panahi, I. An Individualized Super-Gaussian Single Microphone Speech Enhancement for Hearing Aid Users with Smartphone as an Assistive Device. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2017, 24, 1601–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Espejo, I.; Tan, Z.-H.; Jensen, J. Improved external speaker-robust keyword spotting for hearing assistive devices. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2020, 28, 1233–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, A.; Küçük, A.; Panahi, I. Real-time smartphone application for improving spatial awareness of hearing assistive devices. In Proceedings of the 2018 40th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Honolulu, HI, USA, 18–21 July 2018; pp. 433–436. [Google Scholar]

- Skehan, P. Processing perspectives on task performance. In Processing Perspectives on Task Performance; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 1–278. [Google Scholar]

- Tavakoli, P.; Skehan, P. 9. Strategic planning, task structure and performance testing. In Planning and Task Performance in a Second Language; John Benjamins: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 239–273. [Google Scholar]

- Hilton, H. Oral fluency and spoken proficiency: Considerations for research and testing. Meas. L2 Profic. Perspect. SLA 2014, 27, 53. [Google Scholar]

- Niparko, J.K.; Marlowe, A. Hearing aids and cochlear implants. In Oxford Handbook of Auditory Science: The Ear; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 409–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Rau, P.-L.P.; Salvendy, G. Measuring perceived interactivity of mobile advertisements. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2010, 29, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, M.; Akram, M.S. Social media adoption by the academic community: Theoretical insights and empirical evidence from developing countries. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2018, 19, 244–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, D.; Jayaraman, K.; Shariff, D.; Bahari, K.A.; Nor, N.M. The effects of perceived interactivity, perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness on online hotel booking intention: A conceptual framework. Int. Acad. Res. J. Soc. Sci. 2017, 3, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Jiarui, W.; Xiaoli, Z.; Jiafu, S. Interpersonal Relationship, Knowledge Characteristic, and Knowledge Sharing Behavior of Online Community Members: A TAM Perspective. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 4188480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, T.J.; Yong, W.K.; Harmizi, A. Usage of WhatsApp and interpersonal communication skills among private university students. J. Arts Soc. Sci. 2020, 3, 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Mittal, S.; Gera, R.; Batra, D.K. An evaluation of an integrated perspective of perceived service quality for retail banking services in India. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2015, 33, 330–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.K.; Park, S.H.; Kang, J.E.; Choi, K.S.; Kim, H.A.; Jeon, M.S.; Rhie, S.J. The influence of a patient counseling training session on pharmacy students’ self-perceived communication skills, confidence levels, and attitudes about communication skills training. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blood, G.W.; Blood, I.M.; Tellis, G.; Gabel, R. Communication apprehension and self-perceived communication competence in adolescents who stutter. J. Fluen. Disord. 2001, 26, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, M.R.; Power, D.; Horstmanshof, L. Deaf people communicating via SMS, TTY, relay service, fax, and computers in Australia. J. Deaf Stud. Deaf Educ. 2007, 12, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilling, D.; Barrett, P. Text communication preferences of deaf people in the United Kingdom. J. Deaf Stud. Deaf Educ. 2008, 13, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sexton, J. Empowering adolescents who are deaf and hard of hearing. N. Carol. Med. J. 2017, 78, 129–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawes, P.; Maslin, M.; Munro, K.J. ‘Getting used to’hearing aids from the perspective of adult hearing-aid users. Int. J. Audiol. 2014, 53, 861–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backenroth, G.A.; Ahlner, B.H. Quality of life of hearing-impaired persons who have participated in audiological rehabilitation counselling. Int. J. Adv. Couns. 2000, 22, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairani, A.; Ahmad, R.; Marjohan, M. Contribution of self image to interpersonal communication between students in the schools. J. Couns. Educ. Technol. 2019, 2, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez Mosquera, P.M.; Uskul, A.K.; Cross, S.E. The centrality of social image in social psychology. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 41, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Park, H.; Ahn, Y. The influence of tourists’ experience of quality of street foods on destination’s image, life satisfaction, and word of mouth: The moderating impact of food neophobia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Lien, C.-H.; Wang, S.W.; Wang, T.; Dong, W. Event and city image: The effect on revisit intention. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 212–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffernan, E.; Coulson, N.S.; Henshaw, H.; Barry, J.G.; Ferguson, M.A. Understanding the psychosocial experiences of adults with mild-moderate hearing loss: An application of Leventhal’s self-regulatory model. Int. J. Audiol. 2016, 55, S3–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barak, A.; Sadovsky, Y. Internet use and personal empowerment of hearing-impaired adolescents. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2008, 24, 1802–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-P.; Huang, H.-N.; Joe, S.-W.; Ma, H.-C. Learning the Determinants of Satisfaction and Usage Intention of Instant Messaging. CyberPsychol. Behav. 2008, 11, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bénabou, R.; Tirole, J. Self-confidence and personal motivation. Q. J. Econ. 2002, 117, 871–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubis, L.; Fazira, E. Connection Management Self-Concept and Social Support with Student Confidence. Nidhomul Haq: J. Manaj. Pendidik. Islam 2022, 7, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foustanos, A.; Pantazi, L.; Zavrides, H. Representations in Plastic Surgery: The Impact of Self-Image and Self-Confidence in the Work Environment. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2007, 31, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, N.; Evli, M.; Uzdil, N.; Albayrak, E.; Kartal, D. Body Image and Sexual Self-confidence in Patients with Chronic Urticaria. Sex. Disabil. 2020, 38, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G. Why don’t men ever stop to ask for directions? Gender, social influence, and their role in technology acceptance and usage behavior. MIS Q. 2000, 24, 115–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-W.; Gupta, S.; Koh, J. Investigating the intention to purchase digital items in social networking communities: A customer value perspective. Inf. Manag. 2011, 48, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bispo, R.; Branco, V. Designing out Stigma: A New Approach to Designing for Human Diversity; European Academy of Design: Porto, Portugal, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Stankov, L.; Lee, J.; Luo, W.; Hogan, D.J. Confidence: A better predictor of academic achievement than self-efficacy, self-concept and anxiety? Learn. Individ. Differ. 2012, 22, 747–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.-C.; Hwang, M.-Y.; Tai, K.-H.; Tsai, C.-R. An Exploration of Students’ Science Learning Interest Related to Their Cognitive Anxiety, Cognitive Load, Self-Confidence and Learning Progress Using Inquiry-Based Learning with an iPad. Res. Sci. Educ. 2017, 47, 1193–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-S.; Ahn, J.; No, J.-K. Applying the Health Belief Model to college students’ health behavior. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2012, 6, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, C.S.; Lin, P.Y.; Jong, M.S.y.; Dai, Y.; Chiu, T.K.F.; Huang, B. Factors Influencing Students’ Behavioral Intention to Continue Artificial Intelligence Learning. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Symposium on Educational Technology (ISET), Bangkok, Thailand, 24–27 August 2020; pp. 147–150. [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan, T.; Tran, T.P.; Taylor, E.C. Getting to know you: Social media personalization as a means of enhancing brand loyalty and perceived quality. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 47, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-Y.; Wang, Y.-S.; Lin, H.-H.; Tsai, T.-H. Developing and validating a model for assessing paid mobile learning app success. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2019, 27, 458–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.-T.; Chiu, C.-A.; Sung, K.; Farn, C.-K. A comparative study on the flow experience in web-based and text-based interaction environments. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2011, 14, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlaisang, J.; Songkram, N.; Huang, F.; Teo, T. Teachers’ perception of the use of mobile technologies with smart applications to enhance students’ thinking skills: A study among primary school teachers in Thailand. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2023, 31, 5037–5058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.; Campbell, K.S. Follow the Leader? The Impact of Leader Rapport Management on Social Loafing. Bus. Prof. Commun. Q. 2021, 84, 181–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yu, J.; Zo, H.; Choi, M. User acceptance of wearable devices: An extended perspective of perceived value. Telemat. Inform. 2016, 33, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeh, M.T.; Abduljabbar, F.H.; Alqahtani, S.M.; Waly, F.J.; Alnaami, I.; Aljurayyan, A.; Alzaman, N. Students’ satisfaction and continued intention toward e-learning: A theory-based study. Med. Educ. Online 2021, 26, 1961348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.-C.; Lin, P.-H.; Hsieh, P.-C. The effect of consumer innovativeness on perceived value and continuance intention to use smartwatch. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 67, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Wei, W.; Chen, J. A Study on the Impact Mechanisms of Users’ Behavioral Intentions Towards Augmented Reality Picture Books for Adult Readers. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2024, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, A.H.; Malhotra, A.; Segars, A.H. Knowledge management: An organizational capabilities perspective. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2001, 18, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New Challenges to International Marketing; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009; Volume 20, pp. 277–319. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988; pp. 75–108. [Google Scholar]

- Eksvärd, S.; Falk, J. Evaluating Speech-to-Text Systems and AR-glasses: A study to develop a potential assistive device for people with hearing impairments. Student Thesis, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Helvik, A.-S.; Jacobsen, G.; Svebak, S.; Hallberg, L.R.M. Hearing Impairment, Sense of Humour and Communication Strategies. Scand. J. Disabil. Res. 2007, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrenas, M.-L.; Holgers, K.-M. A clinical evaluation of the hearing disability and handicap scale in men with noise induced hearing loss. Noise Health 2000, 2, 67. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- de Miranda, R.S.; Shubert, C.O.; Machado, W.C.A. Communication with people with hearing disabilities: An integrative review. Rev. Pesqui. Cuid. Fundam. Online 2014, 6, 1695–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, J. Communication problems of hearing-impaired patients. Nurs. Stand. (Through 2013) 2000, 14, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bion, W.R. Attention and Interpretation; Jason Aronson: Lanham, MD, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In Political Psychology; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2004; pp. 276–293. [Google Scholar]

- Vicars, W.G. Is Being Deaf a Disability? Available online: https://www.lifeprint.com/asl101/topics/disability-deafness.htm (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Faucett, H.A.; Ringland, K.E.; Cullen, A.L.; Hayes, G.R. (In) visibility in disability and assistive technology. ACM Trans. Access. Comput. (TACCESS) 2017, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Operational Definition | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Function quality | The completeness and quality of functions of AR smart glasses. | Wang and Chuan-Chuan Lin [50] |

| Perceived interaction speed | The response speed of AR smart glasses as perceived by PHI. | Steuer, Biocca and Levy [51] |

| Perceived ease of use | The ease of use of AR smart glasses as perceived by PHI. | Davis [52] |

| Communication effectiveness | The effectiveness and quality of interactions and communication between PHI and others. | Sweeney, Morrison [53] |

| Social image | The views and respect that PHI receive from others. | Lin and Bhattacherjee [54] |

| Confidence | The confidence of PHI that AR glasses can assist them in communication. | Wilkes [55] |

| Behavioral intention | The intention of PHI to use AR smart glasses as hearing aids. | Taylor and Todd [56] |

| Constructs | Items | Content | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Function quality | FQ1 | I feel that the speech-to-text accuracy of AR glasses is very high. | Shanahan, Tran and Taylor [99], Wang, Wang [100] |

| FQ2 | I feel that the speech-to-text quality of AR glasses is high. | ||

| FQ3 | I believe that the information output from the AR glasses is reliable. | ||

| FQ4 | I believe the functionality quality of the AR glasses meets my requirements. | ||

| Perceived interaction speed | PIS1 | I feel that the speech-to-text speed of AR glasses is very fast. | Huang, Chiu [101] |

| PIS2 | I believe the process of speech-to-text with AR glasses is very smooth. | ||

| PIS3 | I believe the speech-to-text speed of AR glasses is almost synchronous with the speed of the other person’s speech. | ||

| PIS4 | I feel that the response speed of the AR glasses is fast when communicating with others. | ||

| Perceived ease of use | PEU1 | Learning how to use AR glasses is easy for me. | Khlaisang, Songkram [102] |

| PEU2 | Interacting with AR glasses doesn’t require much effort. | ||

| PEU3 | I can use AR glasses proficiently in communication. | ||

| Communication effectiveness | CE1 | With the help of AR glasses, I communicate with others more easily and comfortably. | Sweeney, Morrison [53], Lam and Campbell [103] |

| CE2 | With the assistance of AR glasses, I can communicate better with others. | ||

| CE3 | AR glasses help me understand others more effortlessly. | ||

| CE4 | With the assistance of AR glasses, I can communicate with others smoothly and without barriers. | ||

| Social image | SI1 | By using AR glasses, I have shed the image of being hearing-impaired. | Yang, Yu [104] |

| SI2 | By using AR glasses, others see me as a normal person. | ||

| SI3 | Using AR glasses gives others the impression that I am a regular individual. | ||

| Confidence | CO1 | With the help of AR glasses, I now have the confidence to handle the entire communication process. | Hong, Hwang [96] |

| CO2 | Compared to before, with the help of AR glasses, I believe my communication performance is better. | ||

| CO3 | Compared to before, with the assistance of AR glasses, I will communicate with others more confidently. | ||

| Behavioral intention | BI1 | I am willing to use AR glasses as my hearing assistance device. | Rajeh, Abduljabbar [105], Hong, Lin and Hsieh [106] |

| BI2 | I would recommend AR glasses to my hearing-impaired friends. | ||

| BI3 | I will continue to use AR glasses in the future. |

| Category | Group | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 73 | 38.624% |

| Female | 116 | 61.376% | |

| Age | <18 | 12 | 6.349% |

| 18–30 | 100 | 52.910% | |

| 31–40 | 36 | 19.048% | |

| 41–50 | 24 | 12.698% | |

| 51–60 | 14 | 7.407 | |

| >60 | 3 | 1.587 | |

| Education | High school or technical secondary school and below | 55 | 29.101% |

| junior college | 63 | 33.333% | |

| Undergraduate | 65 | 34.392% | |

| Graduate and above | 6 | 3.175% | |

| Degrees of hearing impairment | Mild | 107 | 56.614% |

| Moderate | 77 | 40.741% | |

| Severe | 5 | 2.646% |

| Constructs | Items | Loadings | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability (rho_a) | Composite Reliability (rho_c) | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Function quality | FQ1 | 0.852 | 0.866 | 0.869 | 0.909 | 0.713 |

| FQ2 | 0.844 | |||||

| FQ3 | 0.834 | |||||

| FQ4 | 0.847 | |||||

| Perceived interaction speed | PIS1 | 0.845 | 0.87 | 0.874 | 0.911 | 0.72 |

| PIS2 | 0.868 | |||||

| PIS3 | 0.832 | |||||

| PIS4 | 0.848 | |||||

| Perceived ease of use | PEU1 PEU2 PEU3 | 0.839 | 0.79 | 0.797 | 0.877 | 0.703 |

| 0.824 | ||||||

| 0.853 | ||||||

| Communication effectiveness | CE1 | 0.851 | 0.868 | 0.868 | 0.91 | 0.717 |

| CE2 | 0.86 | |||||

| CE3 | 0.843 | |||||

| CE4 | 0.832 | |||||

| Social image | SI1 | 0.825 | 0.833 | 0.838 | 0.9 | 0.75 |

| SI2 | 0.903 | |||||

| SI3 | 0.869 | |||||

| Confidence | CO1 | 0.876 | 0.843 | 0.845 | 0.905 | 0.761 |

| CO2 | 0.881 | |||||

| CO3 | 0.861 | |||||

| Behavioral intention | BI1 | 0.854 | 0.867 | 0.869 | 0.919 | 0.791 |

| BI2 | 0.897 | |||||

| BI3 | 0.915 |

| FQ | PIS | PEU | CE | SI | CO | BI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FQ | 0.844 | ||||||

| PIS | 0.771 | 0.848 | |||||

| PEU | 0.609 | 0.606 | 0.839 | ||||

| CE | 0.708 | 0.705 | 0.733 | 0.847 | |||

| SI | 0.593 | 0.593 | 0.571 | 0.685 | 0.866 | ||

| CO | 0.589 | 0.569 | 0.616 | 0.707 | 0.724 | 0.873 | |

| BI | 0.589 | 0.586 | 0.645 | 0.763 | 0.683 | 0.748 | 0.889 |

| FQ | PIS | PEU | CE | SI | CO | BI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FQ | |||||||

| PIS | 0.887 | ||||||

| PEU | 0.731 | 0.721 | |||||

| CE | 0.812 | 0.808 | 0.878 | ||||

| SI | 0.696 | 0.695 | 0.698 | 0.805 | |||

| CO | 0.684 | 0.660 | 0.755 | 0.825 | 0.861 | ||

| BI | 0.675 | 0.672 | 0.772 | 0.879 | 0.801 | 0.875 |

| Construct | R2 | Q2 |

|---|---|---|

| Communication effectiveness | 0.669 | 0.472 |

| Social image | 0.469 | 0.348 |

| Confidence | 0.608 | 0.454 |

| Behavior intention | 0.602 | 0.471 |

| Indices | Estimated Model |

|---|---|

| SRMR | 0.082 |

| d_ULS | 2.007 |

| d_G | 0.598 |

| Chi square | 648.539 |

| NFI | 0.804 |

| Hypothesis | Path | Std Beta | t Statistics | p Values | VIF | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | FQ → CE | 0.256 | 3.329 | 0.0001 | 2.674 | Support |

| H2 | PIS → CE | 0.250 | 3.449 | 0.0001 | 2.655 | Support |

| H3 | PEU → CE | 0.426 | 7.618 | 0.0000 | 1.715 | Support |

| H4 | CE → CO | 0.398 | 6.298 | 0.0000 | 1.882 | Support |

| H5 | CE → SI | 0.685 | 16.194 | 0.0000 | 1.000 | Support |

| H6 | SI → CO | 0.451 | 7.337 | 0.0000 | 1.882 | Support |

| H7 | SI → BI | 0.296 | 3.683 | 0.0000 | 2.101 | Support |

| H8 | CO → BI | 0.534 | 7.314 | 0.0000 | 2.101 | Support |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Deng, L.; Chen, J.; Li, D. Factors Influencing Intentions of People with Hearing Impairments to Use Augmented Reality Glasses as Hearing Aids. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 728. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080728

Deng L, Chen J, Li D. Factors Influencing Intentions of People with Hearing Impairments to Use Augmented Reality Glasses as Hearing Aids. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(8):728. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080728

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeng, Liyuan, Jiangjie Chen, and Dongning Li. 2024. "Factors Influencing Intentions of People with Hearing Impairments to Use Augmented Reality Glasses as Hearing Aids" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 8: 728. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080728

APA StyleDeng, L., Chen, J., & Li, D. (2024). Factors Influencing Intentions of People with Hearing Impairments to Use Augmented Reality Glasses as Hearing Aids. Behavioral Sciences, 14(8), 728. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080728