The Impact of Social Support on Burnout among Lecturers: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Related Literature and Research Perspective

1.1.1. Burnout

1.1.2. Social Support

1.1.3. The Relationship between Burnout and Social Support

1.2. Knowledge of Gaps and Aims of Review

2. Materials and Methods

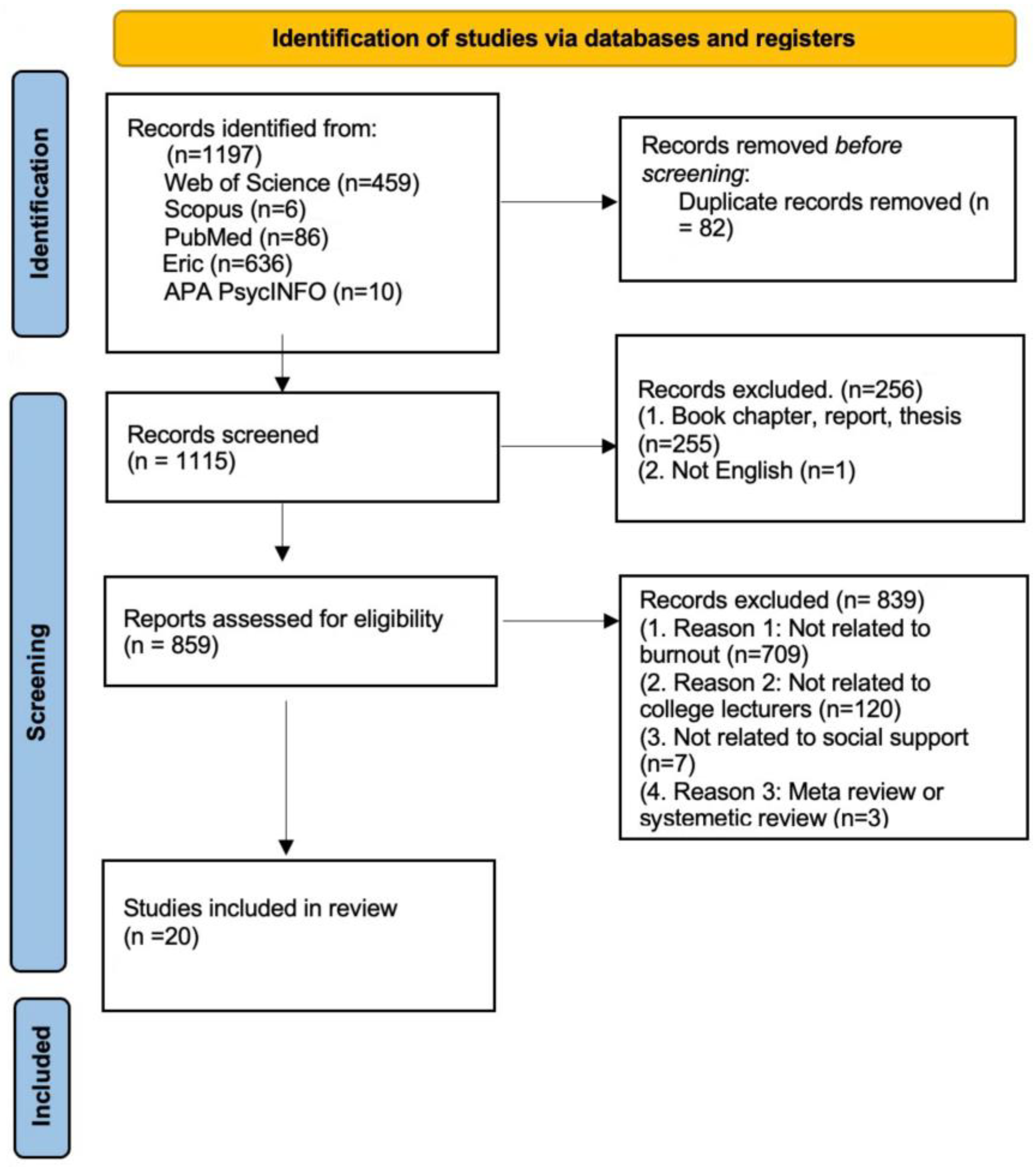

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria for Studies

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Assessment of Included Studies

2.5. Synthesis and Analysis of Results

3. Results

3.1. Contexts and Characteristics of the Studies

3.2. Themes

3.2.1. Measurement of Burnout and Social Support

3.2.2. Factors Influence Lecturers’ Burnout

3.2.3. Mechanisms That Impact Burnout through Social Support

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No. | Authors | Year | Country | Title | Aim(s) | Participant Characteristics | Study Type | Research Design | Main Findings | CCAT Scores |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Siyum [45] | 2023 | Ethiopia | University instructors’ burnout: antecedents and consequences | To examine the antecedents and consequences of burnout among instructors in Ethiopia. | 158 university instructors | cross-sectional study | quantitative research | Work experience, educational status, job characteristics, organizational support, and reward and recognition were reported as primary sources of burnout among instructors. | 38 |

| 2 | Babb et al. [2] | 2022 | Canada | THIS IS US: Latent Profile Analysis of Canadian Teachers’ Burnout during the COVID-19 Pandemic | To explore whether job demands and related internal and external resources are associated with each burnout profile. | 1930 lecturers | cross-sectional study | quantitative research | Time management, technology issues, parents, balancing home and work life, and lack of resources were correlated with exhaustion. | 38 |

| 3 | Carroll et al. [59] | 2022 | Australia | Teacher Stress and Burnout in Australia: Examining the Role of Intrapersonal and Environmental Factors | To explore intrapersonal and environmental factors in relation to teacher stress and burnout. | 749 Australian teachers | cross-sectional study | quantitative research | Emotion regulation, workload, and subjective well-being play a role in the degree of stress and burnout they experience | 37 |

| 4 | Brunsting et al. [50] | 2024 | The United States | Self-Efficacy, Burnout, and Intent to Leave for Teachers of Students with Emotional and Behavioral Disorders | To examinee interrelations between self-efficacy and burnout as well as the relative contribution of each to SETs’ intent to leave their position. | 230 special education teachers | longitudinal study | quantitative research | The significant relationships were unidirectional: dimensions of burnout at earlier timepoints predicted dimensions of self-efficacy at the subsequent timepoint four times, while self-efficacy did not predict burnout at any later timepoints. | 36 |

| 5 | Alamoudi [47] | 2023 | Saudi Arabia | The Relationship between Perceived Autonomy and Work Burnout amongst EFL Teachers | To examine the relationship between autonomy and burnout in the context of EFL teaching. | 158 EFL teachers from four Saudi universities | cross-sectional study | quantitative research | The perception of having high or moderate levels of autonomy is connected to lower rates of burnout | 38 |

| 6 | Kant and Shanker [44] | 2021 | India | Relationship between Emotional Intelligence and Burnout: An Empirical Investigation of Teacher Educators | To explore if a relationship exists or not between emotional intelligence and burnout. | 200 teacher educators | cross-sectional study | quantitative research | Emotional intelligence and burnout syndrome have a strong negative association | 38 |

| 7 | Sánchez et al. [52] | 2019 | Mexico | Psychosocial Factors and Burnout Syndrome in Academics of a Public University from Mexico | To identify the relationship between the psychosocial factors of academic work and burnout syndrome in a public university. | 247 academics | cross-sectional study | quantitative research | There was a statistically significant relationship between all psychosocial factors and most burnout dimensions independent of sex, age, or marital status. | 35 |

| 8 | Roohani and Dayeri [46] | 2019 | Iran | On the Relationship between Iranian EFL Teachers’ Burnout and Motivation: A Mixed Methods Study | To examine the relationship between burnout and teachers’ motivation to teach, and investigate the motivational factors which would predict teacher burnout. | 115 EFL teachers | cross-sectional study | mixed methods | There was a negative relationship between autonomous forms of motivation (intrinsic and identified) and burnout. | 37 |

| 9 | Mahali et al. [48] | 2024 | Canada | Multicultural Efficacy Beliefs in Higher Education: Examining University Instructors’ Burnout and Mental Well-Being | To examine the relationships between multicultural efficacy and university instructors’ burnout and mental well-being. | 158 faculty and sessional instructors | cross-sectional study | quantitative research | Multicultural efficacy was significantly related to the personal accomplishment facet of burnout and mental well-being, even after controlling for variance according to demographics, job-related characteristics, teaching self-efficacy, and color-blind racial attitudes. | 37 |

| 10 | Serin [42] | 2020 | Turkey | The Investigation of the Relationship between Academics’ Person-Organization Fit and Burnout Levels | To determine whether there is a relationship between the burnout syndrome which is related to many organizational factors and the person–organization fit. | 393 academics | cross-sectional study | quantitative research | There is a significant relationship between academics’ person–organization fit and burnout levels, and a significant difference was obtained at burnout levels of academics in terms of their weekly course load, academic titles, whether they have any administrative duties and gender variables. | 34 |

| 11 | Samadi et al. [41] | 2020 | Iran | An Investigation into EFL Instructors’ Intention to Leave and Burnout: Exploring the Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction | To investigate if there are significant relationships between burnout, intention to leave, and job satisfaction among EFL instructors and examine whether job satisfaction mediates the potential relationship between intention to leave and burnout. | 120 EFL instructors | cross-sectional study | quantitative research | There was a moderate relationship between burnout and intention to leave, the instructors’ intention to leave affected their level of burnout and their level of job satisfaction did not matter. | 36 |

| 12 | Taylor and Frechette [9] | 2022 | The United States | The Impact of Workload, Productivity, and Social Support on Burnout among Marketing Faculty during the COVID-19 Pandemic | To examine the impact of the pandemic on faculty workloads and subsequent faculty burnout. | 400 teachers | cross-sectional study | quantitative research | Educators experienced moderate levels of burnout, which was increased by work demands in research and teaching, as well as student interaction, whereas research productivity decreased burnout. Burnout was not influenced by gender, rank, tenure status, or institution type. | 37 |

| 13 | Li et al. [49] | 2020 | China | The impact of teaching-research conflict on job burnout among university teachers: An integrated model | To explore the mechanism underlying the relationship between teaching–research conflict and job burnout among university teachers. | 489 teachers | cross-sectional study | quantitative research | PSS moderated the effect of TRC on both EE and DP but did not act as a moderator in the relationship between TRC and personal accomplishment; PsyCap moderated the effect of TRC on all the three dimensions of job burnout. | 38 |

| 14 | Ghanizadeh and Royaei [40] | 2015 | Iran | Emotional Facet of Language Teaching: Emotion Regulation and Emotional Labor Strategies as Predictors of Teacher Burnout | To examine the hypothesized nexus between emotion regulation, emotional labor strategy, and burnout among EFL teachers. | 153 EFL teachers | cross-sectional study | quantitative research | Teachers’ use of emotional labor strategies can account for about 37% of burnout depletion; the emotional labor strategy of all three strategies correlated most significantly with burnout. | 38 |

| 15 | Kolomitro et al. [62] | 2020 | Canada | A Call to Action: Exploring and Responding to Educational Developers’ Workplace Burnout and Well-Being in Higher Education | To examine the concepts of burnout and workplace well-being among educational developers. | 210 lecturers | cross-sectional study | quantitative research | Characteristics around four themes that both enhanced or hindered participants’ sense of well-being: (a) colleagues, (b) manager/director, (c) institution/senior administration, and d) workplace. | 34 |

| 16 | Coyle et al. [60] | 2020 | The United States | Burnout: Why Are Teacher Educators Reaching Their Limits? | To investigate the variables that may impact burnout for higher education faculty. | 1463 teacher educators | cross-sectional study | mixed research | Educators have a very low to moderate chance of burnout, but experience many of the stressors that can lead to burnout, including workload, control, rewards, community, fairness, and values. | 37 |

| 17 | Castro et al. [54] | 2023 | Portugal | Burnout, resilience, and subjective well-being among Portuguese lecturers’ during the COVID-19 pandemic | To investigate burnout amongst lecturers and analyze potential determinants of burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic. | 331 lecturers from 35 different colleges | cross-sectional study | quantitative research | Personal, work, and student factors related to burnout. Lower levels of resilience, and higher levels of depression and stress were significantly associated with personal and work-related burnout. | 38 |

| 18 | Kaiser et al. [51] | 2021 | Norway | Burnout and Engagement at the Northernmost University in the World | To examine the relationships between job demands, job resources, burnout, and engagement among university staff. | 236 staff from one university | cross-sectional study | quantitative research | Job demands were the most important predictors for burnout, and autonomy was the most important job resource in the prediction of engagement and burnout. | 37 |

| 19 | Padilla and Thompson [43] | 2016 | The United States | Burning out faculty at doctoral research universities | To examine the importance of time allocation, pressure, and support variables together as determinants of faculty burnout. | 1439 lecturers | cross-sectional study | quantitative research | Time allocation variables and perceived pressure contribute to faculty burnout, decreased social support, while family, sleep, and leisure time were related to higher levels of burnout. Grantsmanship and service activities appeared as the most critical factors associated with faculty burnout. | 38 |

| 20 | Mota and Rad [56] | 2023 | Iran | Burnout Experience among Iranian Teachers during the COVID-19 Pandemic | To estimate the prevalence of burnout in Iranian men and women teachers and analyze the association of sociodemographic variables on burnout levels. | 125 Iranian teachers | cross-sectional study | quantitative research | Significant differences were found for sex, with men reporting higher exhaustion than women. No significant differences were found between other sociodemographic characteristics and burnout. | 37 |

References

- Skaalvik, E.M.; Skaalvik, S. Dimensions of Teacher Burnout: Relations with Potential Stressors at School. Soc. Psychol. Educ. Int. J. 2017, 20, 775–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babb, J.; Sokal, L.; Trudel, L.E. THIS IS US: Latent Profile Analysis of Canadian Teachers’ Burnout during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Can. J. Educ. Rev. Can. L’Éducation 2022, 45, 555–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics. Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse/2024-01/mms/en (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- García-Arroyo, J.A.; Segovia, A.O.; Peiró, J.M. Meta-Analytical Review of Teacher Burnout across 36 Societies: The Role of National Learning Assessments and Gender Egalitarianism. Psychol. Health 2019, 34, 733–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boamah, S.A.; Read, E.A.; Spence Laschinger, H.K. Factors Influencing New Graduate Nurse Burnout Development, Job Satisfaction and Patient Care Quality: A Time-Lagged Study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2017, 73, 1182–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, M.M. Study on The Current Status and Relationship of Occupational Stress, Job Burnout and Job Commitment of Preschool Teachers in Western China. Master’s Thesis, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Z.Q. Study on the Current Situation, Causes and Intervention of Job Burnout among Public Foreign Language Teachers in Universities. Master’s Thesis, Northeast Normal University, Changchun, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.N. The Impact of Occupational Stress on Job Burnout among Primary and Secondary School Teachers: The Mediating Role of Social Support and Psychological Empowerment. Master’s Thesis, Shandong Normal University, Jinan, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, D.G.; Frechette, M. The Impact of Workload, Productivity, and Social Support on Burnout among Marketing Faculty during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Mark. Educ. 2022, 44, 134–148. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E.; Leiter, M.P. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual, 3rd ed.; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberger, H.J. Staff Burn-Out. J. Soc. Issues 1974, 30, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. The Measurement of Experienced Burnout. J. Organ. Behav. 1981, 2, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C. Job Burnout: New Directions in Research and Intervention. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2003, 12, 189–192. [Google Scholar]

- Redondo-Flórez, L.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F.; Ramos-Campo, D.J.; Clemente-Suárez, V.J. Gender Differences in Stress- and Burnout-Related Factors of University Professors. Biomed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 6687358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabagh, Z.; Hall, N.C.; Saroyan, A. Antecedents, Correlates and Consequences of Faculty Burnout. Educ. Res. 2018, 60, 131–156. [Google Scholar]

- House, J.S. Work Stress and Social Support; Addison-Wesley Series on Occupational Stress; Addison-Wesley Pub. Co.: Reading, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Wills, T.A. Social Support and Interpersonal Relationships. In Prosocial Behavior; Review of Personality and Social Psychology; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991; Volume 12, pp. 265–289. ISBN 978-0-8039-4071-0. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer, R.; Knoll, N.; Rieckmann, N. Social Support. In Health Psychology; Blackwell Publishing: Malden, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 158–181. ISBN 978-0-631-21441-0. [Google Scholar]

- Iram, A.; Mustafa, M.; Ahmad, S.; Maqsood, S.; Maqsood, F. The Effects of Provision of Instrumental, Emotional, and Informational Support on Psychosocial Adjustment of Involuntary Childless Women in Pakistan. J. Fam. Issues 2021, 42, 2289–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.Y. Theoretical basis and research application of social support rating scale. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1994, 4, 98–100. [Google Scholar]

- Zimet, G.D.; Dahlem, N.W.; Zimet, S.G.; Farley, G.K. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J. Personal. Assess. 1988, 52, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, L. A Study on The Relationship Between Job Burnout, Social Support and Mental Health of Urban and Rural Primary School Teachers. Master’s Thesis, Northwest Normal University, Lanzhou, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Maas, J.; Schoch, S.; Scholz, U.; Rackow, P.; Schüler, J.; Wegner, M.; Keller, R. Teachers’ perceived time pressure, emotional exhaustion and the role of social support from the school principal. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2021, 24, 441–464. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, P.; Yand, K.R.; Li, X.C.; Qin, J. Research on the problems and countermeasures of social support and job burnout of college teachers. Educ. Acad. Mon. 2020, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Greenglass, E.R.; Fiksenbaum, L.; Burke, R.J. The Relationship Between Social Support and Burnout Over Time in Teachers. In Occupational Stress; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1995; ISBN 978-1-00-307243-0. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mansour, K. Stress and Turnover Intention among Healthcare Workers in Saudi Arabia during the Time of COVID-19: Can Social Support Play a Role? PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winding, T.N.; Aust, B.; Andersen, L.P.S. The Association between Pupils’ Aggressive Behaviour and Burnout among Danish School Teachers-the Role of Stress and Social Support at Work. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.Z. A Study on The Relationship between Stress and Internalized Problems among College Teachers: The Stress Buffering Effect of Social Support. Technol. Style 2021, 173–175. [Google Scholar]

- Duru, E.; Balkis, M. Exposure to School Violence at School and Mental Health of Victimized Adolescents: The Mediation Role of Social Support. Child Abus. Negl. 2018, 76, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golovchanova, N.; Owiredua, C.; Boersma, K.; Andershed, H.; Hellfeldt, K. Presence of Meaning in Life in Older Men and Women: The Role of Dimensions of Frailty and Social Support. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 730724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Ren, Z.; Wang, Q.; He, M.; Xiong, W.; Ma, G.; Zhang, X. The relationship between job stress and job burnout: The mediating effects of perceived social support and job satisfaction. Psychol. Health Med. 2021, 26, 204–211. [Google Scholar]

- Velando-Soriano, A.; Ortega-Campos, E.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Ramírez-Baena, L.; De La Fuente, E.I.; Cañadas-De La Fuente, G.A. Impact of social support in preventing burnout syndrome in nurses: A systematic review. Jpn. J. Nurs. Sci. 2020, 17, e12269. [Google Scholar]

- Park, E.-Y.; Shin, M. A Meta-Analysis of Special Education Teachers’ Burnout. Sage Open 2020, 10, 2158244020918297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 151, W-65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, R.; Knafl, K. The Integrative Review: Updated Methodology. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, A.; Smith, D.; Booth, A. Beyond PICO: The SPIDER Tool for Qualitative Evidence Synthesis. Qual. Health Res. 2012, 22, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, M.B.; Frandsen, T.F. The Impact of Patient, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome (PICO) as a Search Strategy Tool on Literature Search Quality: A Systematic Review. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2018, 106, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Thematic Analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 12, 297–298. [Google Scholar]

- Ghanizadeh, A.; Royaei, N. Emotional Facet of Language Teaching: Emotion Regulation and Emotional Labor Strategies as Predictors of Teacher Burnout. Int. J. Pedagog. Learn. 2015, 10, 139–150. [Google Scholar]

- Samadi, L.; Bagheri, M.S.; Sadighi, F.; Yarmohammadi, L. An Investigation into EFL Instructors’ Intention to Leave and Burnout: Exploring the Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction. Cogent Educ. 2020, 7, 1781430. [Google Scholar]

- Serin, A.A.H. The Investigation of the Relationship Between Academics’ Person-Organization Fit and Burnout Levels. Int. J. Progress. Educ. 2020, 16, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, M.A.; Thompson, J.N. Burning out Faculty at Doctoral Research Universities. Stress Health J. Int. Soc. Investig. Stress 2016, 32, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, R.; Shanker, A. Relationship between Emotional Intelligence and Burnout: An Empirical Investigation of Teacher Educators. Int. J. Eval. Res. Educ. 2021, 10, 966–975. [Google Scholar]

- Siyum, B.A. University Instructors’ Burnout: Antecedents and Consequences. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2023, 15, 1056–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roohani, A.; Dayeri, K. On the Relationship between Iranian EFL Teachers’ Burnout and Motivation: A Mixed Methods Study. Iran. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 2019, 7, 77–99. [Google Scholar]

- Alamoudi, K. The Relationship between Perceived Autonomy and Work Burnout amongst EFL Teachers. Int. J. Res. Educ. Sci. 2023, 9, 389–406. [Google Scholar]

- Mahali, S.C.; Sevigny, P.R.; Beshai, S. Multicultural Efficacy Beliefs in Higher Education: Examining University Instructors’ Burnout and Mental Well-Being. Psychol. Rep. 2024, 332941241253599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Castaño, G. The Impact of Teaching-Research Conflict on Job Burnout among University Teachers: An Integrated Model. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2020, 31, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunsting, N.C.; Stark, K.; Bettini, E.; Lane, K.L.; Royer, D.J.; Common, E.A.; Rock, M.L. Self-Efficacy, Burnout, and Intent to Leave for Teachers of Students with Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. Behav. Disord. 2024, 49, 75–90. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, S.; Richardsen, A.M.; Martinussen, M. Burnout and Engagement at the Northernmost University in the World. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 21582440211031552. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, D.V.; García, A.J.; González Corzo, I.; Moreno, M.O. Psychosocial Factors and Burnout Syndrome in Academics of a Public University from Mexico. J. Educ. Psychol.-Propos. Represent. 2019, 7, 127–142. [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Monte, P.R.; Cortés, V.S.N.; Gil-Monte, P.R.; Cortés, V.S.N. Estructura factorial del Cuestionario para la Evaluación del Síndrome de Quemarse por el Trabajo en maestros Mexicanos de educación primaria. Rev. Mex. Psicol. 2011, 28, 75–84. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, L.; Serrão, C.; Rodrigues, A.R.; Marina, S.; dos Santos, J.P.M.; Amorim-Lopes, T.S.; Miguel, C.; Teixeira, A.; Duarte, I. Burnout, Resilience, and Subjective Well-Being among Portuguese Lecturers’ during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1271004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, T.S.; Borritz, M.; Villadsen, E.; Christensen, K.B. The Copenhagen Burnout Inventory: A New Tool for the Assessment of Burnout. Work Stress 2005, 19, 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, A.I.; Rad, J.A. Burnout Experience among Iranian Teachers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. High. Educ. Stud. 2023, 13, 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Demerouti, E.; Mostert, K.; Bakker, A.B. Burnout and Work Engagement: A Thorough Investigation of the Independency of Both Constructs. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Armeli, S.; Rexwinkel, B.; Lynch, P.D.; Rhoades, L. Reciprocation of Perceived Organizational Support. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.; Forrest, K.; Sanders-O’Connor, E.; Flynn, L.; Bower, J.M.; Fynes-Clinton, S.; York, A.; Ziaei, M. Teacher Stress and Burnout in Australia: Examining the Role of Intrapersonal and Environmental Factors. Soc. Psychol. Educ. Int. J. 2022, 25, 441–469. [Google Scholar]

- Coyle, T.; Cotto, C.R. Burnout: Why Are Teacher Educators Reaching Their Limits? Excelsior Leadersh. Teach. Learn. 2020, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier, C.J.; Wong, V.; McGrew, J.H.; Ruble, L.A.; Worrell, F.C. Stress, Burnout, and Mental Health among Teachers of Color. Learn. Prof. 2021, 42, 54. [Google Scholar]

- Kolomitro, K.; Kenny, N.; Sheffield, S.L.-M. A Call to Action: Exploring and Responding to Educational Developers’ Workplace Burnout and Well-Being in Higher Education. Int. J. Acad. Dev. 2020, 25, 5–18. [Google Scholar]

| Search Query | Keywords in Title, Abstract, and Keyword |

|---|---|

| 1 | “burnout” OR “burn-out” OR “burned out” |

| 2 | “Social support” OR “family support” OR “informational support” OR “emotional support” OR “financial support” OR “instrumental support” |

| 3 | “lecturers” OR “university instructors” OR “college instructors” |

| Final | 1 + 2 + 3 |

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Population | College lecturers | Primary and secondary school teachers, professors |

| Interventions | None | None |

| Comparisons | None | None |

| Country setting | Any country | None |

| Outcomes | Studies that analyze relationships between social support and burnout | Social support not related to burnout |

| Setting | Studies with broad definitions of social support and burnout | Studies not related to social support or burnout |

| Language | English or translated into English. | Not in English |

| Study types and designs | Quantitative research Qualitative research Mixed Research | Studies without empirical data |

| Variables | Measurement |

|---|---|

| Burnout | Maslach Burnout Inventory—Educators Survey (MBI-ES) |

| Maslach Burnout Inventory—General Survey (MBI-GS) | |

| Burnout Syndrome Evaluation Questionnaire (CESQT-PE) | |

| Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI) | |

| Shirom–Melamed Burnout Measure (SMBM) | |

| Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI) | |

| Social support | Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) |

| Perceived Organizational Support (SPOS) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cao, B.; Hassan, N.C.; Omar, M.K. The Impact of Social Support on Burnout among Lecturers: A Systematic Literature Review. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 727. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080727

Cao B, Hassan NC, Omar MK. The Impact of Social Support on Burnout among Lecturers: A Systematic Literature Review. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(8):727. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080727

Chicago/Turabian StyleCao, Beibei, Norlizah Che Hassan, and Muhd Khaizer Omar. 2024. "The Impact of Social Support on Burnout among Lecturers: A Systematic Literature Review" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 8: 727. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080727

APA StyleCao, B., Hassan, N. C., & Omar, M. K. (2024). The Impact of Social Support on Burnout among Lecturers: A Systematic Literature Review. Behavioral Sciences, 14(8), 727. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080727