Unraveling the Link between Perceived ESG and Psychological Well-Being: The Moderated Mediating Roles of Job Meaningfulness and Pay Satisfaction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Conservation of Resources Theory

2.2. Perceived ESG and Psychological Well-Being

2.3. Mediating Role of Job Meaningfulness

2.4. Moderating Effect of Pay Satisfaction and Its Moderated Mediation

3. Methods

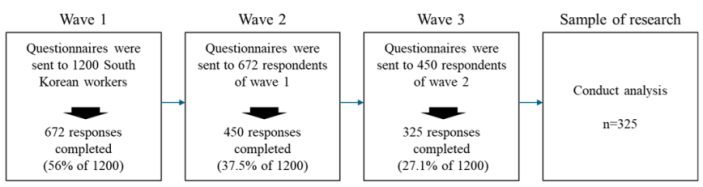

3.1. Sample Collection Procedure and Characteristics

3.2. Measurements

3.2.1. Perceived ESG

3.2.2. Pay Satisfaction

3.2.3. Job Meaningfulness

3.2.4. Psychological Well-Being

3.2.5. Control Variables

3.3. Common Method Bias

3.4. Analytical Strategy

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Research Limitations and Future Research Directions

5.4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Sampling Procedure

Appendix B. Measurement

- Our company is committed to using a portion of its profit to help nonprofits.

- Our company gives back to the communities in which it does business.

- Local nonprofits benefit from our company’s contributions.

- Our company integrates charitable contributions into its business activities.

- Our company is involved in corporate giving.

- I am satisfied with my overall level of pay.

- I am satisfied with my current salary.

- I am satisfied with my take-home pay.

- I am satisfied with the size of my current salary.

- The work I do is very important to me.

- My job activities are personally meaningful to me.

- The work I do is meaningful to me.

- Some people wander aimlessly through life, but I am not one of them.

- I live life one day at a time and do not really think about the future. (R)

- I sometimes feel as if I have done all there is to do in life. (R)

- 4.

- For me, life has been a continuous process of learning, changing, and growth.

- 5.

- I think it is important to have new experiences to challenge how I think about myself and the world.

- 6.

- I gave up trying to make big improvements or changes in my life a long time ago. (R)

References

- Galbreath, J. ESG in focus: The Australian evidence. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 118, 529–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.; Mahrous, A.A. Nation branding: The strategic imperative for sustainable market competitiveness. J. Humanit. Appl. Soc. Sci. 2019, 1, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friede, G.; Busch, T.; Bassen, A. ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. J. Sustain. Financ. Investig. 2015, 5, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillan, S.; Hartzell, J.C.; Koch, A.; Starks, L.T. Firms’ environmental, social and governance (ESG) choices, performance and managerial motivation. Unpubl. Work. Pap. 2010, 10, 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Peiris, D.; Evans, J. The relationship between environmental social governance factors and US stock performance. J. Investig. 2010, 19, 104–112. [Google Scholar]

- Cornell, B.; Shapiro, A.C. Corporate stakeholders, corporate valuation and ESG. Eur. Financ. Manag. 2021, 27, 196–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escrig-Olmedo, E.; Fernández-Izquierdo, M.Á.; Ferrero-Ferrero, I.; Rivera-Lirio, J.M.; Muñoz-Torres, M.J. Rating the raters: Evaluating how ESG rating agencies integrate sustainability principles. Sustainability 2019, 11, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aouadi, A.; Marsat, S. Do ESG controversies matter for firm value? Evidence from international data. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 1027–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassen, R.; Hinze, A.-K.; Hardeck, I. Impact of ESG factors on firm risk in Europe. J. Bus. Econ. 2016, 86, 867–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leins, S. ‘Responsible investment’: ESG and the post-crisis ethical order. Econ. Soc. 2020, 49, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekhili, M.; Boukadhaba, A.; Nagati, H.; Chtioui, T. ESG performance and market value: The moderating role of employee board representation. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 32, 3061–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.E.; Mallory, D.B. Corporate social responsibility: Psychological, person-centric, and progressing. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2015, 2, 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.-G.; Kang, S.-W.; Choi, S.B. A multilevel study of the relationship between csr promotion climate and happiness at work via organizational identification: Moderation effect of leader–followers value congruence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parfitt, C. ESG integration treats ethics as risk, but whose ethics and whose risk? Responsible investment in the context of precarity and risk-shifting. Crit. Sociol. 2020, 46, 573–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.Z. Environmental, social and governance (ESG) activity and firm performance: A review and consolidation. Account. Financ. 2021, 61, 335–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.-G.; Choi, S.B.; Kang, S.-W. Leader’s perception of corporate social responsibility and team members’ psychological well-being: Mediating effects of value congruence climate and pro-social behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, M.; Kim, B. The effects of ESG activity recognition of corporate employees on job performance: The case of South Korea. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaškevičiūtė, V.; Zsigmond, T.; Berke, S.; Berber, N. Investigating the impact of person-organization fit on employee well-being in uncertain conditions: A study in three central European countries. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2024, 46, 188–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Sanz-Vergel, A. Job demands–resources theory: Ten years later. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2023, 10, 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources. A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J.R.; Neveu, J.P.; Paustian-Underdahl, S.C.; Westman, M. Getting to the “COR” understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 1334–1364. [Google Scholar]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roeck, K.; Maon, F. Building the theoretical puzzle of employees’ reactions to corporate social responsibility: An integrative conceptual framework and research agenda. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 149, 609–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Halbesleben, J.; Neveu, J.P.; Westman, M. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Park, Y.; Kim, B.; Lee, C.K. Impact of perceptions of ESG on organization-based self-esteem, commitment, and intention to stay. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2024, 41, 106–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekhili, M.; Boukadhaba, A.; Nagati, H. The ESG–financial performance relationship: Does the type of employee board representation matter? Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2021, 29, 134–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, W.M.W.; Wasiuzzaman, S. Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) disclosure, competitive advantage and performance of firms in Malaysia. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2021, 2, 100015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BaniMelhem, H.; Elanain, H.M.A.; Hussain, M. Impact of human resource management practices on employees’ turnover intention in United Arab Emirates (UAE) health care services. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Serv. Sect. 2018, 10, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, N.R.; Mónico, L.; Pais, L.; Gagné, M.; Forest, J.; Cabral, P.M.F.; Ferraro, T. The multidimensional work motivation scale: Psychometric studies in Portugal and Brazil. Manag. Res. J. Iberoam. Acad. Manag. 2022, 20, 89–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.; Chouaibi, J.; Chouaibi, S.; Jilani, W.; Chouaibi, Y. Does a board characteristic moderate the relationship between CSR practices and financial performance? Evidence from European ESG firms. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, R. Corporate reputation: Meaning and measurement. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2005, 7, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, R.; Argandoña, A.; Choirat, C.; Siegel, D.S. Corporate reputation: Being good and looking good. Bus. Soc. 2019, 58, 1132–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamm, E.; Tosti-Kharas, J.; King, C.E. Empowering employee sustainability: Perceived organizational support toward the environment. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 128, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D.; Singer, B. The contours of positive human health. Psychol. Inq. 1998, 9, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Kang, S.-W.; Choi, S.B. Servant leadership and creativity: A study of the sequential mediating roles of psychological safety and employee well-being. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 807070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D.; Davidson, R. National Survey of Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS II): Neuroscience Project; Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Kang, S.-W.; Choi, S.B. Effects of employee well-being and self-efficacy on the relationship between coaching leadership and knowledge sharing intention: A study of UK and US employees. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, T.A.; Hobfoll, S.E. Commitment, psychological well-being and job performance: An examination of conservation of resources (COR) theory and job burnout. J. Bus. Manag. 2004, 9, 389. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E. The Science of Well-Being: The Collected Works of Ed Diener; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; Volume 37. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, J.-G.; Kang, S.-W.; Choi, S.B. Employees’ weekend activities and psychological well-being via job stress: A moderated mediation role of recovery experience. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, R.H.; Ashforth, B.E.; Diefendorff, J.M. The bright side of emotional labor. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 36, 749–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Kang, S.W.; Choi, S.B.; Jeung, W. Abusive supervision and psychological well-being: The mediating role of self-determination and moderating role of perceived person-organization fit. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2024, 45, 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.M. Psychological Empowerment in the Workplace: Dimensions, Measurement, and Validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 1442–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K.W.; Velthouse, B.A. Cognitive Elements of Empowerment: An “Interpretive” Model of Intrinsic Task Motivation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1990, 15, 666–681. [Google Scholar]

- Khusanova, R.; Kang, S.-W.; Choi, S.B. Work engagement among public employees: Antecedents and consequences. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 684495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spreitzer, G.; Sutcliffe, K.; Dutton, J.; Sonenshein, S.; Grant, A.M. A socially embedded model of thriving at work. Organ. Sci. 2005, 16, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godinic, D.; Obrenovic, B.; Khudaykulov, A. Effects of Economic Uncertainty on Mental Health in the COVID-19 Pandemic Context: Social Identity Disturbance, Job Uncertainty and Psychological Well-Being Model. Int. J. Innov. Econ. Dev. 2020, 6, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killingsworth, M.A.; Kahneman, D.; Mellers, B. Income and emotional well-being: A conflict resolved. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2208661120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iannello, P.; Sorgente, A.; Lanz, M.; Antonietti, A. Financial well-being and its relationship with subjective and psychological well-being among emerging adults: Testing the moderating effect of individual differences. J. Happiness Stud. 2021, 22, 1385–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, U.; Tavares, S.M.; Carvalho, H.; Ramalho, J.J.; Santos, S.C.; Van Veldhoven, M. Self-employment and eudaimonic well-being: Energized by meaning, enabled by societal legitimacy. J. Bus. Ventur. 2020, 35, 106047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, R.M.; Igelström, E.; Purba, A.K.; Shimonovich, M.; Thomson, H.; McCartney, G. How do income changes impact on mental health and wellbeing for working-age adults? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e515–e528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, M.A.; Yoon, H.; Kang, S.W.; You, M. How to mitigate the negative effect of emotional exhaustion among healthcare workers: The role of safety climate and compensation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Piccolo, R.F.; Podsakoff, N.P.; Shaw, J.C.; Rich, B.L. The relationship between pay and job satisfaction: A meta-analysis of the literature. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 77, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, K.M.; O’Brien, K.E.; Beehr, T.A. The role of hindrance stressors in the job demand–control–support model of occupational stress: A proposed theory revision. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 37, 397–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Cross-Cultural Research Methods, in Environment and Culture; Altman, I., Rapoport, A., Wohlwill, J.F., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; pp. 47–82. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein, D.R.; Drumwright, M.E.; Braig, B.M. The effect of corporate social responsibility on customer donations to corporate-supported nonprofits. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heneman, H.G., III; Schwab, D.P. Pay satisfaction: Its multidimensional nature and measurement. Int. J. Psychol. 1985, 20, 129–141. [Google Scholar]

- Waterman, A.S. Two conceptions of happiness: Contrasts of personal expressiveness (eudaimonia) and hedonic enjoyment. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 64, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernerth, J.B.; Aguinis, H. A critical review and best-practice recommendations for control variable usage. Pers. Psychol. 2016, 69, 229–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilmaghani, M.; Tabvuma, V. The gender gap in work–life balance satisfaction across occupations. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2019, 34, 398–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, M. Effects of job satisfaction on the worker’s wage and weekly hours: A simultaneous equations approach. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 2019, 79, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, C.M.; Simmering, M.J.; Atinc, G.; Atinc, Y.; Babin, B.J. Common methods variance detection in business research. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3192–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Commun. Monogr. 2018, 85, 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; Sage publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, E. Effects of skewness and kurtosis on normal-theory based maximum likelihood test statistic in multilevel structural equation modeling. Behav. Res. Methods 2011, 43, 1066–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Krok, D.; Zarzycka, B. Risk perception of COVID-19, meaning-based resources and psychological well-being amongst healthcare personnel: The mediating role of coping. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, R. Stakeholder Theory and Organizational Ethics; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: Oakland, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, S. Stakeholder: Essentially contested or just confused? J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 108, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xie, G. ESG disclosure and financial performance: Moderating role of ESG investors. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2022, 83, 102291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suttipun, M. The influence of board composition on environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosure of Thai listed companies. Int. J. Discl. Gov. 2021, 18, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmat, N.H.C.; Arendt, S.W.; Russell, D.W. Effects of minimum wage policy implementation: Compensation, work behaviors, and quality of life. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 81, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Wang, S. Research progress and prospect of environmental, social and governance: A systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 447, 141489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiden, C.; Silaban, A. Exploring the Measurement of Environmental Performance in Alignment with Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG): A Qualitative Study. Inf. Sci. Lett. 2023, 12, 2287–2297. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 41.78 | 10.97 | - | ||||||||

| 2. Female | 0.50 | 0.50 | −0.09 | - | |||||||

| 3. Education | 2.50 | 0.92 | −0.14 * | 0.03 | - | ||||||

| 4. Tenure | 7.67 | 6.84 | −0.12 * | 0.44 *** | 0.01 | - | |||||

| 5. Child | 0.49 | 0.50 | −0.13 * | 0.47 *** | 0.10 | 0.27 *** | - | ||||

| 6. Perceived ESG | 2.49 | 0.97 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.19 *** | 0.08 | 0.10 | (0.95) | |||

| 7. Job meaningfulness | 3.40 | 0.84 | 0.22 *** | −0.01 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.33 *** | 0.21 *** | (0.97) | ||

| 8. Pay satisfaction | 2.40 | 0.92 | 0.14 ** | −0.10 | 0.07 | 0.15 ** | 0.15 ** | 0.23 *** | 0.29 *** | (0.89) | |

| 9. Psychological well-being | 3.38 | 0.73 | 0.06 | −0.08 | 0.15 ** | −0.01 | 0.19 *** | 0.29 *** | 0.47 *** | 0.23 *** | (0.90) |

| Model | χ2(df) | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | Δχ2(Δdf) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research model (4 factor) | 309.43(199) *** | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.04 | |

| Alternative model 1 (3 factor) 1 | 1957.62(207) *** | 0.85 | 0.82 | 0.09 | 1648.19(8) *** |

| Alternative model 2 (2 factor) 2 | 2581.50(214) *** | 0.70 | 0.65 | 0.13 | 2272.07(15) *** |

| Alternative model 3 (1 factor) 3 | 3580.54(220) *** | 0.48 | 0.42 | 0.17 | 3271.11(21) *** |

| Variable | Job Meaningfulness | Psychological Well-Being | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

| Age | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.02 | −0.08 | −0.06 | −0.08 |

| Female | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.06 | −0.05 | −0.05 | −0.07 |

| Education | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.14 * | 0.09 | 0.07 |

| Tenure | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.07 | −0.06 | −0.08 | −0.06 |

| Child | 0.33 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.31 *** | 0.26 *** | 0.22 ** | 0.10 |

| Perceived ESG | 0.17 ** | 0.13 * | 0.25 *** | 0.18 *** | ||

| Pay satisfaction | 0.22 *** | |||||

| ESG × Pay satisfaction | 0.12 * | |||||

| Job meaningfulness | 0.41 *** | |||||

| R2 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.27 |

| ΔR2 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.14 | ||

| adj R2 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.26 |

| F | 8.55 *** | 9.03 *** | 10.23 *** | 4.72 *** | 7.85 *** | 17.01 *** |

| Finc | 10.19 ** | 11.95 *** | 21.93 *** | 62.85 *** | ||

| Dependent Variable: Psychological Well-Being | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediating Variable | Indirect Effect | SE | 95% CI | |

| LLCI | ULCI | |||

| Job meaningfulness | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.1 |

| Dependent Variable: Psychological Well-Being | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderating Variable | Level of Moderator | Indirect Effect | SE | 95% CI | |

| LLCI | ULCI | ||||

| Pay satisfaction | Low (−1 SD) | 0.02 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.08 |

| High (+1 SD) | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.12 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choi, W.-S.; Wang, W.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, J.; Kang, S.-W. Unraveling the Link between Perceived ESG and Psychological Well-Being: The Moderated Mediating Roles of Job Meaningfulness and Pay Satisfaction. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 606. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070606

Choi W-S, Wang W, Kim HJ, Lee J, Kang S-W. Unraveling the Link between Perceived ESG and Psychological Well-Being: The Moderated Mediating Roles of Job Meaningfulness and Pay Satisfaction. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(7):606. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070606

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Woo-Sung, Wenxian Wang, Hee Jin Kim, Jiman Lee, and Seung-Wan Kang. 2024. "Unraveling the Link between Perceived ESG and Psychological Well-Being: The Moderated Mediating Roles of Job Meaningfulness and Pay Satisfaction" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 7: 606. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070606

APA StyleChoi, W.-S., Wang, W., Kim, H. J., Lee, J., & Kang, S.-W. (2024). Unraveling the Link between Perceived ESG and Psychological Well-Being: The Moderated Mediating Roles of Job Meaningfulness and Pay Satisfaction. Behavioral Sciences, 14(7), 606. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070606