The Effect of Coach–Athlete Relationships on Motor Behaviour in College Athletes—Mediating Effects of Psychological Needs

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

1.2. The Present Study

2. Research Objects and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measurement Tools

2.2.1. Coach–Athlete Relationship

2.2.2. Psychological Needs

2.2.3. Motor Behaviour

3. Research Results

3.1. Primary Analysis

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

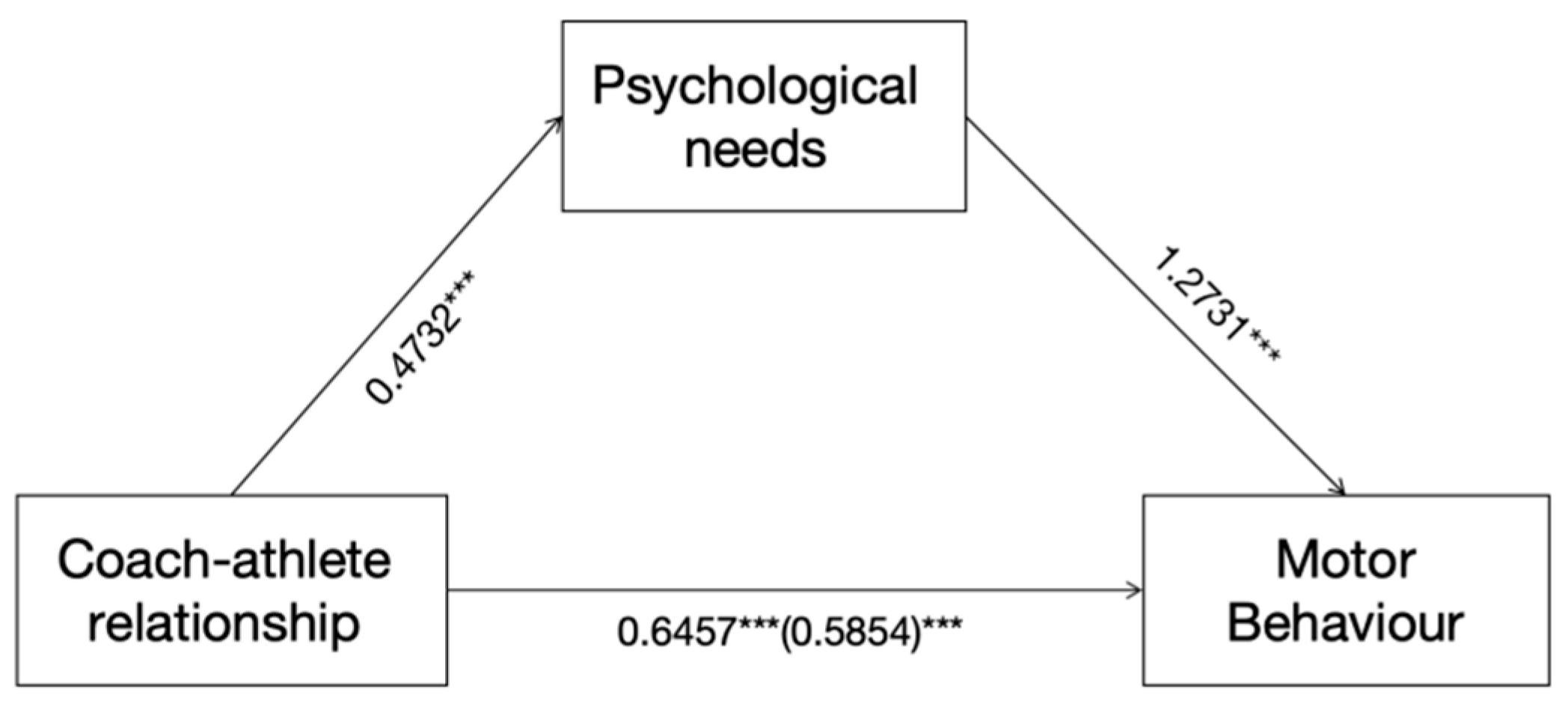

3.3. Path Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Direct Effects of Coach–Athlete Relationships on Psychological Needs and Motor Behaviour

4.2. Mediating Effects of Psychological Needs between Coach–Athlete Relationship and Motor Behaviour

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Simons, E.E.; Bird, M.D. Coach-athlete relationship, social support, and sport-related psychological well-being in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I student-athletes. J. Study Sports Athl. Educ. 2023, 17, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jowett, S.; Cockerill, I.M. Olympic medallists’ perspective of the athlete-coach relationship. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2003, 4, 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jowett, S.; Nicolas, M.; Yang, S. Unravelling the links between coach behaviours and coach-athlete relationships. Eur. J. Sports Exerc. Sci. 2017, 5, 10–19. [Google Scholar]

- Jelleli, H.; Hindawi, O.; Kaddech, N.; Rebhi, M.; Ben, A.M.; Saidane, M.; Dergaa, I. Reliability and validity of the Arabic version of coach-athlete relationship questionnaire: ACART-Q. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2023, 9, 2282275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Sun, H.; Zhong, Y.; Yuan, T. A new species of the genus Pseudourostyla (Hymenoptera, Braconidae) from China. An analysis of Sun Haiping’s hurdles training concept and practice—Based on the perspective of individualised training. J. Shanghai Inst. Phys. Educ. 2011, 2023, 52–63. [Google Scholar]

- Roux, V.; Martinent, G.; Trouilloud, D. Temporal dynamics of the quality of the coach-athlete relationship over one season among adolescent handball players: A latent class analysis approach. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2023, 21, 1107–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.F.; Cordente, M.C.; Ospina, B.J. Examining the psychometric properties of the Coach-Athlete Relationship Questionnaire (CART-Q) with basketball players in China and Spain. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1273606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jowett, S. Coaching effectiveness: The coach–athlete relationship at its heart. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 16, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Connaughton, D.P.; Hedlund, D.P. Youth Sport Coaches’ Perceptions of Sexually Inappropriate Behaviors and Intimate Coach-Athlete Relationships. J. Child Sex. Abus. 2023, 32, 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, L.; Santos, R.; Coelho-e-Silva, M.; Draper, C.; Mota, J.; Jidovtseff, B.; Agostinis-Sobrinho, C. A narrative review of motor competence in children and adolescents: What we know and what we need to find out. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jowett, S.; Nascimento-Júnior, J.; Roberto, A.; Zhao, C.; Gosai, J. Creating the conditions for psychological safety and its impact on quality coach-athlete relationships. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2023, 65, 102363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scales, P.C. The Compete-Learn-Honor Approach to Coaching and Player Development: Promoting Performance Growth While Enhancing Well-Being. J. Sport Psychol. Action 2023, 14, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, M.A.; Solli, G.S.; Talsnes, R.K.; Moen, F. Place of residence and coach-athlete relationship predict drop-out from competitive cross-country skiing. Front. Sports Act. Living 2023, 5, 1110060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, S.; Peng, W.X.; Du, F.Y.; Fang, X.M.; Guan, Z.X.; He, X.L.; Jiang, X.L. Association between coach-athlete relationship and athlete engagement in Chinese team sports: The mediating effect of thriving. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0289979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomerleau-Fontaine, L.; Bloom, G.A.; Alexander, D. Wheelchair Basketball Athletes’ Perceptions of the Coach–Athlete Relationship. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 2022, 40, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonteyn, M.; Haerens, L.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Loeys, T. It takes two to tango: Using the actor-partner interdependence model for studying the coach-athlete relationship. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2022, 63, 102273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsollier, É.; Hauw, D. Navigating in the Gray Area of Coach-Athlete Relationships in Sports: Toward an In-depth Analysis of the Dynamics of Athlete Maltreatment Experiences. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 859372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanford, J.R.; Healy, L.C.; Sarkar, M.; Johnston, J.P. Interpersonal perceptions of personality traits in elite coach-athlete dyads. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2022, 60, 102154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, A.R.; Levy, A.R.; Jones, L.; Meir, R.; Radcliffe, J.N.; Perry, J.L. Committed relationships and enhanced threat levels: Perceptions of coach behavior, the coach–athlete relationship, stress appraisals, and coping among athletes. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2016, 11, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinent, G.; Ferrand, C. Are facilitating emotions really facilitative? A field study of the relationships between discrete emotions and objective performance during competition. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2020, 15, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-García, H.; Martinent, G.; Nicolas, M. Relationships between coach’s leadership, group cohesion, affective states, sport satisfaction and goal attainment in competitive settings. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2022, 17, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, A.B.; Kim, H.D. Leadership preferences of adolescent players in sport: Influence of coach gender. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2017, 16, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Efstratopoulou, M.; Opoku, M.P.; El Howeris, H.; AlQahtani, O. Assessing children at risk in the United Arab Emirates: Validation of the Arabic version of the Motor Behaviour Checklist (MBC) for use in primary school settings. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2023, 136, 104489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulton, R.H.; Rudie, K.; Dukelow, S.P.; Benson, B.W.; Scott, S.H. Capacity Limits Lead to Information Bottlenecks in Ongoing Rapid Motor Behaviors. Eneuro 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugan, B.J.; Lee, H.; Peever, J. Glutamate neurons in the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus control arousal state and motor behaviour in mice. Sleep 2023, 46, zsac322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, S.C.; Martin, L.J.; Ramos, J.; Côté, J. How coach leadership is related to the coach-athlete relationship in elite sport. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2021, 16, 1239–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, D.M.; Kavanagh, E.J.; Polman, R.C. A path analysis of adolescent athletes’ perceived stress reactivity, competition appraisals, emotions, coping, and performance satisfaction. Front. Psychol. 2017, 10, 453124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jowett, S.; Ntoumanis, N. The coach–athlete relationship questionnaire (CART-Q): Development and initial validation. Scandinavian. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2004, 14, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, D.H.; Kim, S. The effects of consumer knowledge on message processing of electronic word-of-mouth via online consumer reviews. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2008, 7, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R.D.; Ramnani, N.; Mackay, C.; Wilson, J.L.; Jezzard, P.; Carter, C.S.; Smith, S.M. Distinct portions of anterior cingulate cortex and medial prefrontal cortex are activated by reward processing in separable phases of decision-making cognition. Biol. Psychiatry 2004, 55, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2015, 50, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephen, S.A.; Habeeb, C.M.; Arthur, C.A. Congruence of efficacy beliefs on the coach-athlete relationship and athlete anxiety: Athlete self-efficacy and coach estimation of athlete self-efficacy. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2022, 58, 102062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, F.; Blakey, M.; Foulds, J.; Steven, H.K.; Hoffmann, S.M. Behaviors and Actions of the Strength and Conditioning Coach in Fostering a Positive Coach-Athlete Relationship. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2021, 36, 3256–3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papich, M.; Bloom, G.A.; Dohme, L.C. Building Successful Coach-Athlete Relationships Using Interpersonal Skills and Emotional Intelligence. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2021, 43, S83. [Google Scholar]

- Hadadi, N.E. Coach Created Motivational Climate and Self-Efficacy in the Coach-Athlete Relationship: The Role of Relational Efficacy Beliefs; East Carolina University: Greenville, NC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Endo, T.; Maekawa, F.; Tohyama, C. Development of an automated cognitive behavioral testing method for juvenile mice in a group-housed environment and its application to developmental neurotoxicological study. Toxicol. Lett. 2021, 350, S139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, A.J.; Flores, C.M.; Pineda, G.C.; Luque, S.A.; La, T.R. Role of Immersive Virtual Reality in Motor Behaviour Decision-Making in Chronic Pain Patients. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laaber, F.; Koch, T.; Hubert, M.; Florack, A. Young People digital maturity relates to different forms of well-being through basic psychological need satisfaction and frustration. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 152, 108077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, S.Y.; Lee, G. Association of Basic Psychological Need Fulfillment and School Happiness with Obesity Levels and Intensity of Physical Activity during Physical Education Classes in South Korean Adolescents. Healthcare 2023, 12, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Jiang, Q.; Cheng, M.; Rhim, Y.T. The effect of smartphone addiction on adolescent health: The moderating effect of leisure physical activities. Psicol. Reflexão Crítica 2024, 37, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bräuninger, I.; Röösli, P. Promoting social-emotional skills and reducing behavioural problems in children through group psychomotor therapy: A randomized controlled trial. Arts Psychother. 2023, 85, 102051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doron, J.; Hayotte, M.; d’Arripe-Longueville, F.; Leprince, C. Coping profiles of adolescent football players and association with interpersonal coping: Do emotional competence and psychological need satisfaction matter? Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2024, 34, e14550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guertin, R.; Malo, M.G.; Marie, H. Switching off automatic pilot to promote wellbeing and performance in the workplace: The role of mindfulness and basic psychological needs satisfaction. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1277416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ameloot, E.; Rotsaert, T.; Ameloot, T.; Rienties, B.S.T. Supporting students’ basic psychological needs and satisfaction in a blended learning environment through learning analytics. Comput. Educ. 2024, 209, 104949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leow, S.; Leow, K.E.; Catherine, L.C. Satisfaction of basic psychological needs and eudaimonic well-being among first-year university students. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2023, 9, 2275441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, J.; Linnane, C.; Baraks, V.; Mille, C. Is individualised care more effective than pre-determined exercises, in a group environment for shoulder conditions? A service evaluation. Physiotherapy 2022, 114, e185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Wang, J.; Chung, A.; Ho, L.C.; Molina, J.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, W.T. The Impact of the Group Environment on the Molecular Gas and Star Formation Activity. Proc. Int. Astron. Union 2021, 17, 136–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrião, A.; Mariano, S.; Mariano, J.; Gavaia, P.J.; Cancela, M.L.; Vitorino, M.; Conceição, N. Mef2ca and mef2cb Double Mutant Zebrafish Show Altered Craniofacial Phenotype and Motor Behaviour. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchi, C.M.; Filogna, S.; Martini, G.; Beani, E.; Maselli, M.; Cianchetti, M.; Sgandurra, G. Wearable accelerometers for measuring and monitoring the motor behaviour of infants with brain damage during CareToy-Revised training. J. Neuro Eng. Rehabil. 2023, 20, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-García, H.; Martinent, G.; Nicolas, M. The mediating roles of pre-competitive coping and affective states in the relationships between coach-athlete relationship, satisfaction and attainment of achievement goals. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Number | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 141 | 55.51% |

| Female | 113 | 44.49% | |

| Grades | Freshman | 36 | 14.17% |

| Sophomore | 42 | 16.54% | |

| Junior | 22 | 8.66% | |

| Senior | 154 | 60.63% | |

| Sports event | Soccer | 77 | 30.31% |

| Basketball | 26 | 10.24% | |

| Volleyball | 17 | 6.69% | |

| Track and field | 55 | 21.65% | |

| Tennis balls | 20 | 7.87% | |

| Others | 59 | 23.23% | |

| Major | Physical education | 177 | 69.69% |

| Non-physical education | 77 | 30.31% | |

| χ2/df | CFI | TLI | SRMR | RMESA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 4.922 *** | 0.683 | 0.667 | 0.103 | 0.109 |

| Model 2 | 2.791 *** | 0.856 | 0.849 | 0.090 | 0.074 |

| Variable | M | SD | Kurtosis | Cronbach’s Alpha | Skewness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intimacy | 19.37 | 2.861 | 15.070 | 0.947 | −3.307 |

| Complementarity | 19.32 | 2.156 | 1.964 | 0.951 | −1.1278 |

| Dedication | 18.38 | 2.694 | 3.824 | 0.922 | −1.711 |

| Coach–athlete relationships | 57.07 | 7.067 | 9.045 | 0.943 | −2.448 |

| Relevance | 18.89 | 3.302 | −0.881 | 0.836 | 0.183 |

| Autonomy | 12.46 | 2.023 | 0.370 | 0.887 | −0.705 |

| Sense of capability | 18.38 | 2.255 | 5.175 | 0.851 | −1.818 |

| Psychological needs | 49.73 | 6.065 | 2.363 | 0.853 | −0.807 |

| Intrinsic | 69.30 | 9.084 | 6.020 | 0.951 | −2.067 |

| Identified | 55.18 | 6.699 | 5.785 | 0.963 | −1.844 |

| External | 15.33 | 3.764 | −1.009 | 0.969 | 0.089 |

| Motor behaviour | 139.81 | 17.004 | 4.951 | 0.958 | −1.583 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Intimacy | 1 | |||||||||||

| 2. Complementarity | 0.800 *** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 3. Dedication | 0.743 *** | 0.735 *** | 1 | |||||||||

| 4. Coach–athlete relationships | 0.932 *** | 0.909 *** | 0.906 *** | 1 | ||||||||

| 5. Relevance | 0.271 *** | 0.273 *** | 0.432 *** | 0.357 *** | 1 | |||||||

| 6. Autonomy | 0.271 *** | 0.249 *** | 0.141 * | 0.239 *** | 0.512 *** | 1 | ||||||

| 7. Sense of capability | 0.738 *** | 0.663 *** | 0.641 *** | 0.745 *** | 0.351 *** | 0.510 *** | 1 | |||||

| 8. Psychological needs | 0.512 *** | 0.478 *** | 0.520 *** | 0.551 *** | 0.845 *** | 0.802 *** | 0.773 *** | 1 | ||||

| 9. Intrinsic | 0.509 *** | 0.414 *** | 0.363 *** | 0.471 *** | 0.261 *** | 0.470 *** | 0.389 *** | 0.443 *** | 1 | |||

| 10. Identified | 0.446 *** | 0.427 *** | 0.383 *** | 0.457 *** | 0.458 *** | 0.628 *** | 0.487 *** | 0.640 *** | 0.758 *** | 1 | ||

| 11. External | 0.269 *** | 0.468 *** | 0.292 *** | 0.363 *** | 0.428 *** | 0.303 *** | 0.319 *** | 0.453 *** | 0.401 *** | 0.553 *** | 1 | |

| 12. Motor behaviour | 0.507 *** | 0.493 *** | 0.410 *** | 0.512 *** | 0.415 *** | 0.566 *** | 0.471 *** | 0.589 *** | 0.992 *** | 0.921 *** | 0.645 *** | 1 |

| Path Relationship | β | SE | z | Bootstrap 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Coach–athlete relationships → Psychological needs | 0.50 | 0.05 | 9.00 | 0.35 | 0.55 | <0.001 |

| Psychological needs → Motor behaviour | 0.35 | 0.07 | 4.29 | 0.16 | 0.44 | <0.001 |

| Coach–athlete relationships → Motor behaviour | 0.25 | 0.06 | 3.33 | 0.08 | 0.32 | <0.001 |

| Coach–athlete relationships → Psychological needs → Motor behaviour | 0.175 | 0.04 | 3.50 | 0.06 | 0.22 | <0.001 |

| Predictor Variable | Equation (1) Psychological Needs | Equation (2) Motor Behaviour | Equation (3) Psychological Needs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | t | B | SE | t | B | SE | t | |

| Coach–athlete relationship | 0.4732 | 0.0451 | 10.492 *** | 0.2433 | 0.0521 | 4.5697 *** | |||

| Psychological needs | 1.2371 | 0.1647 | 7.5134 *** | ||||||

| Coach–athlete relationship × Motor behaviour | −0.0116 | 0.0050 | −2.3083 * | ||||||

| R2 | 0.3040 | 0.3974 | 0.3236 | ||||||

| F | 100.0767 | 82.7565 | 39.8637 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, R.; Rhim, Y.-T. The Effect of Coach–Athlete Relationships on Motor Behaviour in College Athletes—Mediating Effects of Psychological Needs. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 579. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070579

Zhang R, Rhim Y-T. The Effect of Coach–Athlete Relationships on Motor Behaviour in College Athletes—Mediating Effects of Psychological Needs. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(7):579. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070579

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Rong, and Yong-Taek Rhim. 2024. "The Effect of Coach–Athlete Relationships on Motor Behaviour in College Athletes—Mediating Effects of Psychological Needs" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 7: 579. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070579

APA StyleZhang, R., & Rhim, Y.-T. (2024). The Effect of Coach–Athlete Relationships on Motor Behaviour in College Athletes—Mediating Effects of Psychological Needs. Behavioral Sciences, 14(7), 579. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070579