The Effect of Psychological Flexibility on Well-Being during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Multiple Mediation Role of Mindfulness and Coping

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Impacts of COVID-19

1.2. Psychological Flexibility and Well Being

1.3. Psychological Flexibility and Coping Strategies

1.4. Psychological Flexibility and Mindfulness

1.5. Psychological Flexibility, Well-Being, Mindfulness, and Coping Strategies

1.6. Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. PsyFlex

2.2.2. Mental Health Continuum Short Form (MHC-SF)—Adult Version

2.2.3. Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale-Revised (CAMS-R)

2.2.4. Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced Inventory (Brief-COPE)

2.3. Procedure and Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Correlation Analysis

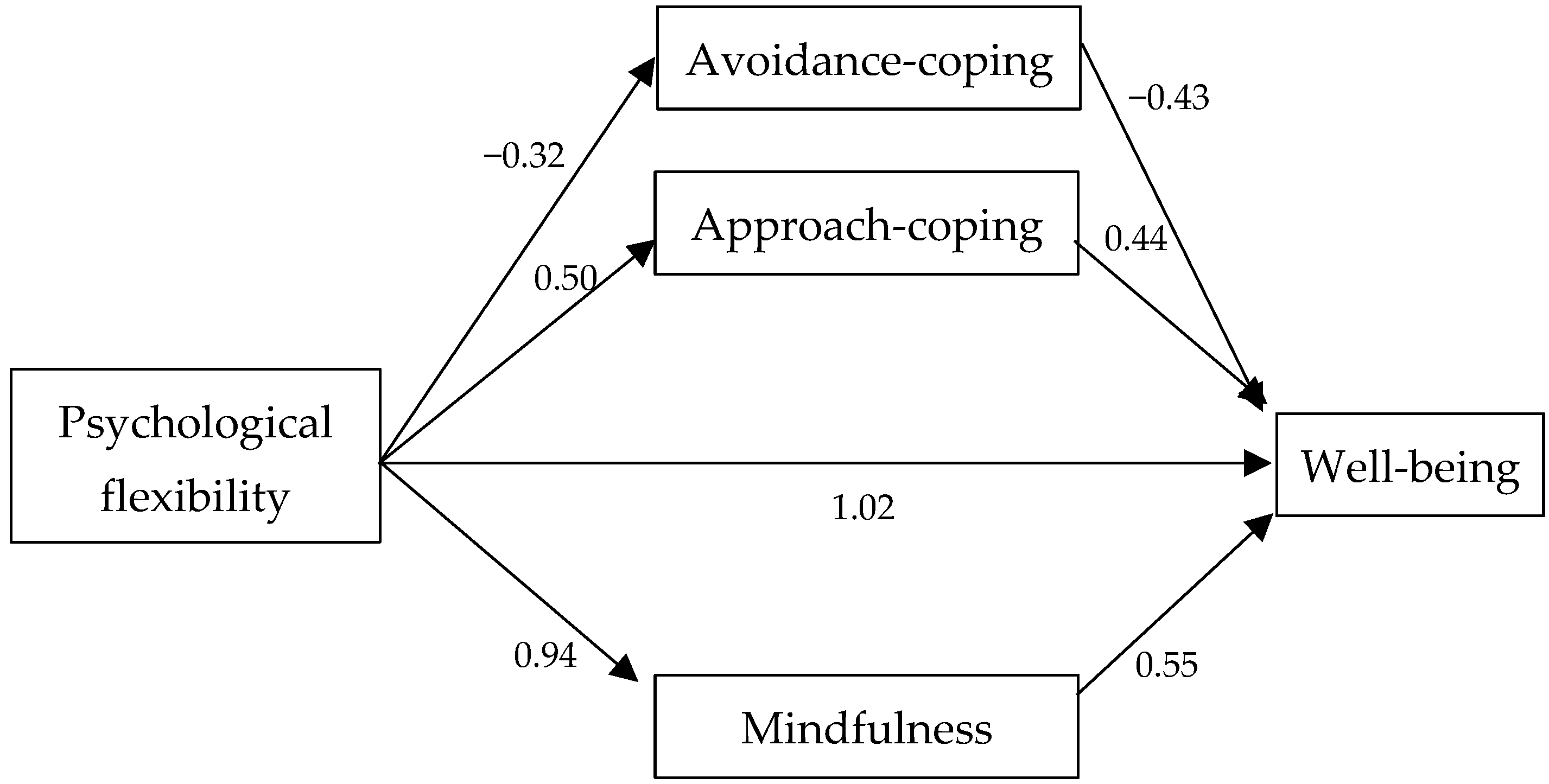

3.2. Multiple Parallel Mediation Analysis

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Karageorghis, C.I.; Bird, J.M.; Hutchinson, J.C.; Hamer, M.; Delevoye-Turrell, Y.N.; Guérin, S.M.; Mullin, E.M.; Mellano, K.T.; Parsons-Smith, R.L.; Terry, V.R.; et al. Physical activity and mental well-being under COVID-19 lockdown: A cross-sectional multination study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloster, A.T.; Lamnisos, D.; Lubenko, J.; Presti, G.; Squatrito, V.; Constantinou, M.; Nicolaou, C.; Papacostas, S.; Aydin, G.; Chong, Y.Y.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health: An international study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0244809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvar, S.Y.; Ghamari, N.; Pezeshkian, F.; Shahriarirad, R. Prevalence of anxiety, depression, stress, and perceived stress and their relation with resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic, a cross-sectional study. Health Sci. Rep. 2022, 5, e460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, D.D.; Silva, A.N. The Mental Health Impacts of a Pandemic: A Multiaxial Conceptual Model for COVID-19. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Strosahl, K.D.; Bunting, K.; Twohig, M.; Wilson, K.G. What is acceptance and commitment therapy? In A Practical Guide to Acceptance and Commitment Therapy; Hayes, S.C., Strosahl, K.D., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 3–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, S.C.; Strosahl, K.D.; Wilson, K.G. Acceptance and commitment therapy. In The Process and Practice of Mindful Change, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashdan, T.B.; Rottenberg, J. Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 865–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doorley, J.D.; Goodman, F.R.; Kelso, K.C.; Kashdan, T.B. Psychological flexibility: What we know, what we do not know, and what we think we know. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2020, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, D.L.; Golijani-Moghaddam, N. COVID-19: Psychological flexibility, coping, mental health, and wellbeing in the UK during the pandemic. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2020, 17, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroska, E.B.; Roche, A.I.; Adamowicz, J.L.; Stegall, M.S. Psychological flexibility in the context of COVID-19 adversity: Associations with distress. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2020, 18, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, A.; Tully, E.C. The role of mindfulness and psychological flexibility in somatisation, depression, anxiety, and general psychological distress in a nonclinical college sample. J. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 17, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, S.; Trindade, I.A.; Mendes, A.L.; Ferreira, C. The buffer role of psychological flexibility against the impact of major life events on depression symptoms. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 24, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakenham, K.I.; Landi, G.; Boccolini, G.; Furlani, A.; Grandi, S.; Tossani, E. The moderating roles of psychological flexibility and inflexibility on the mental health impacts of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown in Italy. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2020, 17, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arslan, G.; Yıldırım, M.; Tanhan, A.; Buluş, M.; Allen, K.A. Coronavirus stress, optimism-pessimism, psychological inflexibility, and psychological health: Psychometric properties of the coronavirus stress measure. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 2, 2423–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gloster, A.T.; Meyer, A.H.; Lieb, R. Psychological flexibility as a malleable public health target: Evidence from a representative sample. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2017, 6, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tindle, R.; Moustafa, A.A. Psychological distress, social support, and psychological flexibility during COVID-19. In Mental Health Effects of COVID-19; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda, B.; Valls, E. Is the Effect of Psychological Inflexibility on Symptoms and Quality of Life Mediated by Coping Strategies in Patients with Mental Disorders? Int. J. Cogn. Ther. 2020, 13, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, F.; Hayes, S. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and the Cognitive Behavioral Tradition. In The Science of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wielgus, B.; Urban, W.; Patriak, A.; Cichocki, Ł. Examining the Associations between Psychological Flexibility, Mindfulness, Psychosomatic Functioning, and Anxiety during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Path Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silberstein, L.R.; Tirch, D.; Leahy, R.L.; McGinn, L. Mindfulness, psychological flexibility and emotional schemas. Int. J. Cogn. Ther. 2012, 5, 406–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, D.D.; Silva, A.N.; Roberto, M.S.; Lubenko, J.; Constantinou, M.; Nicolaou, C.; Lamnisos, D.; Papacostas, S.; Höfer, S.; Presti, G.; et al. Illness Perceptions of COVID-19 in Europe: Predictors, Impacts and Temporal Evolution. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 640955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloster, A.T.; Block, V.J.; Klotsche, J.; Villanueva, J.; Rinner, M.T.B.; Benoy, C.; Walter, M.; Karekla, M.; Bader, K. Psy-Flex: A contextually sensitive measure of psychological flexibility. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2021, 22, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, D.D.; Mouadeb, D.; Lemos, N.; Silva, A.N.; Gloster, A.T.; Perez, W.F. Contextual Similarities in Psychological Flexibility: The Brazil-Portugal Transcultural Adaptation of Psy-Flex. Curr. Psychol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C.L.; Wissing, M.; Potgieter, J.P.; Temane, M.; Kruger, A.; van Rooy, S. Evaluation of the Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF) in Setswana-speaking South Africans. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2008, 15, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, F.; Fonseca, A.; Pereira, M.; Canavarro, M.C. Measuring Positive Mental Health in the Postpartum Period: The Bifactor Structure of the Mental Health Continuum–Short Form in Portuguese Women. Assessment 2021, 28, 1434–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, G.; Hayes, A.; Kumar, S.; Greeson, J.; Laurenceau, J.P. Mindfulness and Emotion Regulation: The Development and Initial Validation of the Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale-Revised (CAMS-R). J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2007, 29, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Full Catastrophe Living: The Program of the Stress Reduction Clinic at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center; Delta: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, S.R.; Lau, M.; Shapiro, S.; Carlson, L.; Anderson, N.D.; Carmody, J.; Devins, G. Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2004, 11, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, R.; Ferreira, G.; Pereira, G. Portuguese validation of the Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale-Revised and the Philadelphia Mindfulness Scale. Mindfulness Compassion 2017, 2, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S. You want to measure coping but your protocol is too long: Consider the brief cope. Int. J. Behav. Med. 1997, 4, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, S.A.; Shen, B.-J.; Schwarz, E.R.; Mallon, S. Avoidant coping moderates the association between anxiety and patient-rated physical functioning in heart failure patients. J. Behav. Med. 2012, 35, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pais-Ribeiro, J.; Rodrigues, A. Questões acerca do coping: A propósito do estudo de adaptação do Brief COPE. Psicol. Saúde Doenças 2004, 5, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Igartua, J.J.; Hayes, A.F. Mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: Concepts, computations, and some common confusions. Span. J. Psychol. 2021, 24, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, P.; Ross, J.; Moriarty, J.; Mallett, J.; Schroder, H.; Ravalier, J.; Manthorpe, J.; Currie, D.; Harron, J.; Gillen, P. The Role of Coping in the Wellbeing and Work-Related Quality of Life of UK Health and Social Care Workers during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J.; Skinner, E.A.; Modecki, K.L.; Webb, H.J.; Gardner, A.A.; Hawes, T.; Rapee, R.M. The self-perception of flexible coping with stress: A new measure and relations with emotional adjustment. Cogent Psychol. 2018, 5, 1537908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditton, E.; Knott, B.; Hodyl, N.; Horton, G.; Walker, F.R.; Nilsson, M. Assessing the Efficacy of an Individualised Psychological Flexibility Skills Training Intervention App for Medical Student Burnout and Well-being: Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2022, 11, e32992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puolakanaho, A.; Olvanen, A.; Markkula, S.; Lappalainen, R. A psychological flexibility -based intervention for Burnout: A randomised controlled trial. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2019, 15, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliliunas, D.; Belisle, J.; Dixon, M.R. A Randomized Control Trial to Evaluate the Use of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) to Increase Academic Performance and Psychological Flexibility in Graduate Students. Behav. Anal. Pract. 2018, 11, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Lee, J. Effects of Acceptance Commitment Therapy Based Recovery Enhancement Program on Psychological Flexibility, Recovery Attitude, and Quality of Life for Inpatients with Mental Illness. J. Korean Acad. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 28, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didonna, F. Clinical Handbook of Mindfulness; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Psychological Flexibility | Well-Being | Avoidance Coping | Approach Coping | Mindfulness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological flexibility | - | 0.487 ** | −0.195 ** | 0.233 ** | 0.609 ** |

| Well-being | 0.487 ** | - | −0.170 ** | 0.347 ** | 0.495 ** |

| Avoidance coping | −0.195 ** | −0.170 ** | - | 0.235 ** | −0.256 ** |

| Approach coping | 0.233 ** | 0.347 ** | 0.235 ** | - | 0.250 ** |

| Mindfulness | 0.609 ** | 0.495 ** | −0.256 ** | 0.250 ** | - |

| Well-Being (R2= 0.39; p = 0.00) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point Estimates | Confidence Products | 95% CI | ||||

| β | SE | T | p | Lower Limit | Upper Limit | |

| Psychological flexibility | 1.02 | 0.20 | 4.98 | 0.00 | 0.62 | 1.43 |

| Mindfulness | 0.55 | 0.14 | 3.97 | 0.00 | 0.28 | 0.83 |

| Approach coping | 0.44 | 0.08 | 4.98 | 0.00 | 0.27 | 0.62 |

| Avoidance coping | −0.43 | 0.16 | −2.59 | 0.00 | −0.76 | −0.10 |

| Bootstrap Times | 5000 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | Lower Limit | Upper Limit | ||

| Mindfulness | 0.52 | 0.13 | 0.27 | 0.79 | |

| Approach coping | Indirect effect | 0.22 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.37 |

| Avoidance coping | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.27 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Paiva, T.; Silva, A.N.d.; Neto, D.D.; Karekla, M.; Kassianos, A.P.; Gloster, A. The Effect of Psychological Flexibility on Well-Being during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Multiple Mediation Role of Mindfulness and Coping. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 545. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070545

Paiva T, Silva ANd, Neto DD, Karekla M, Kassianos AP, Gloster A. The Effect of Psychological Flexibility on Well-Being during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Multiple Mediation Role of Mindfulness and Coping. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(7):545. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070545

Chicago/Turabian StylePaiva, Thiago, Ana Nunes da Silva, David Dias Neto, Maria Karekla, Angelos P. Kassianos, and Andrew Gloster. 2024. "The Effect of Psychological Flexibility on Well-Being during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Multiple Mediation Role of Mindfulness and Coping" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 7: 545. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070545

APA StylePaiva, T., Silva, A. N. d., Neto, D. D., Karekla, M., Kassianos, A. P., & Gloster, A. (2024). The Effect of Psychological Flexibility on Well-Being during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Multiple Mediation Role of Mindfulness and Coping. Behavioral Sciences, 14(7), 545. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070545