The Impact of Parental Autonomy Support on Family Adaptation in the Context of “Double Reduction”: The Mediating Role of Parent–Child Communication and Cohesion

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Impact of Parental Autonomy Support on Family Adaptation in the Context of the “Double Reduction”

1.2. The Mediating Role of Parent–Child Communication

1.3. The Mediating Role of Parent–Child Cohesion

1.4. Chain Mediation of Parent–Child Communication and Parent–Child Cohesion

1.5. The Present Study

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedures

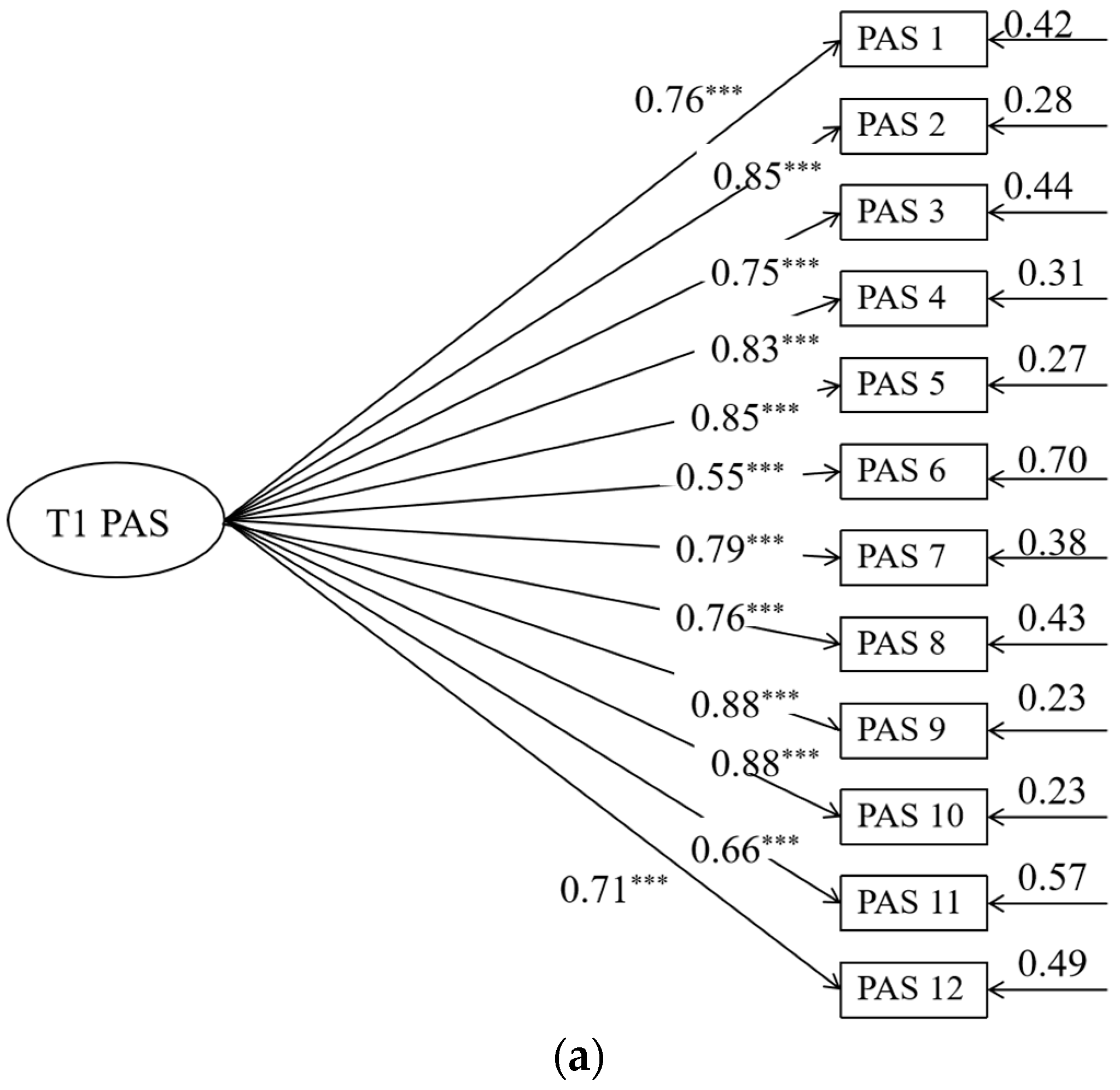

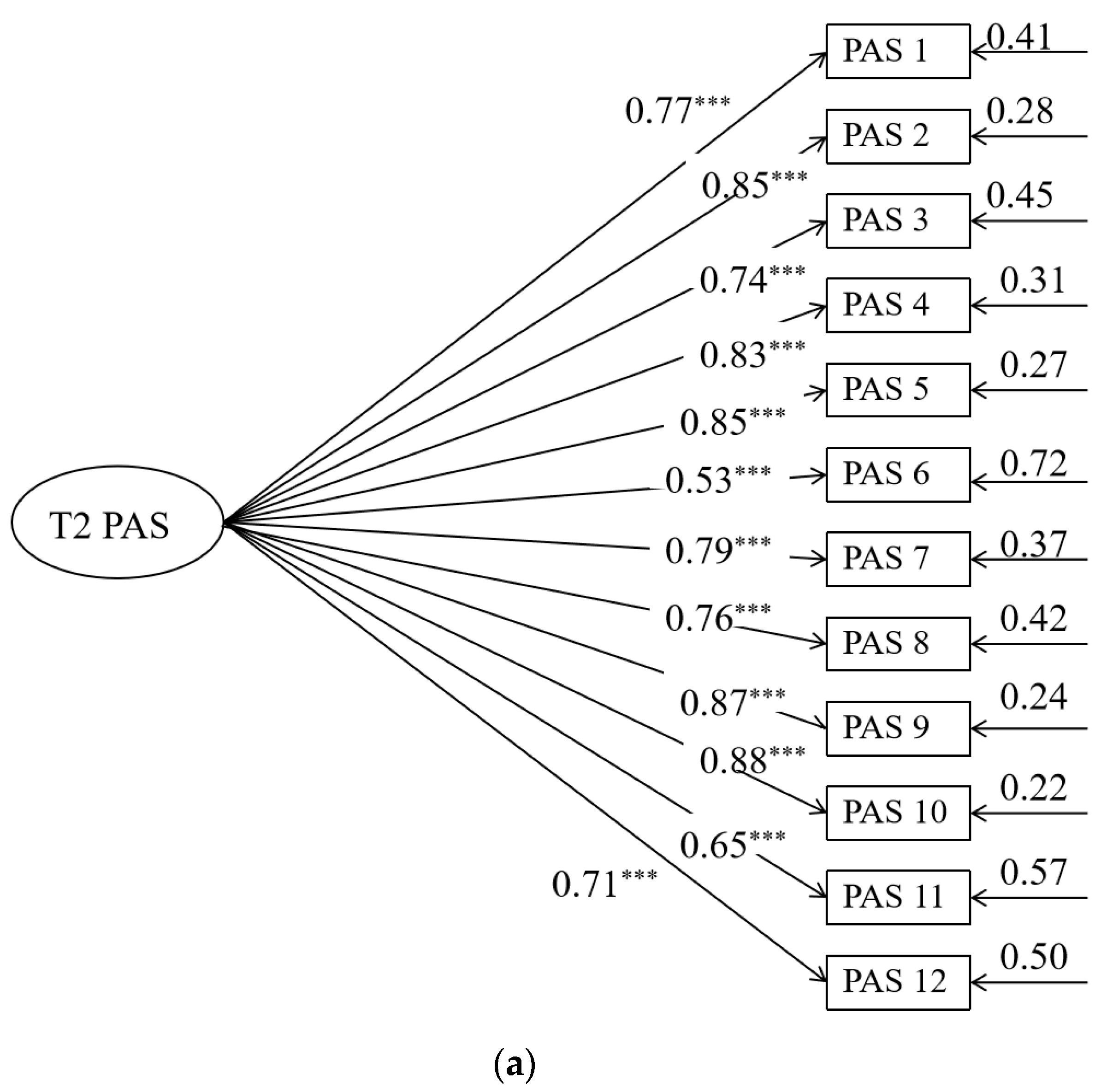

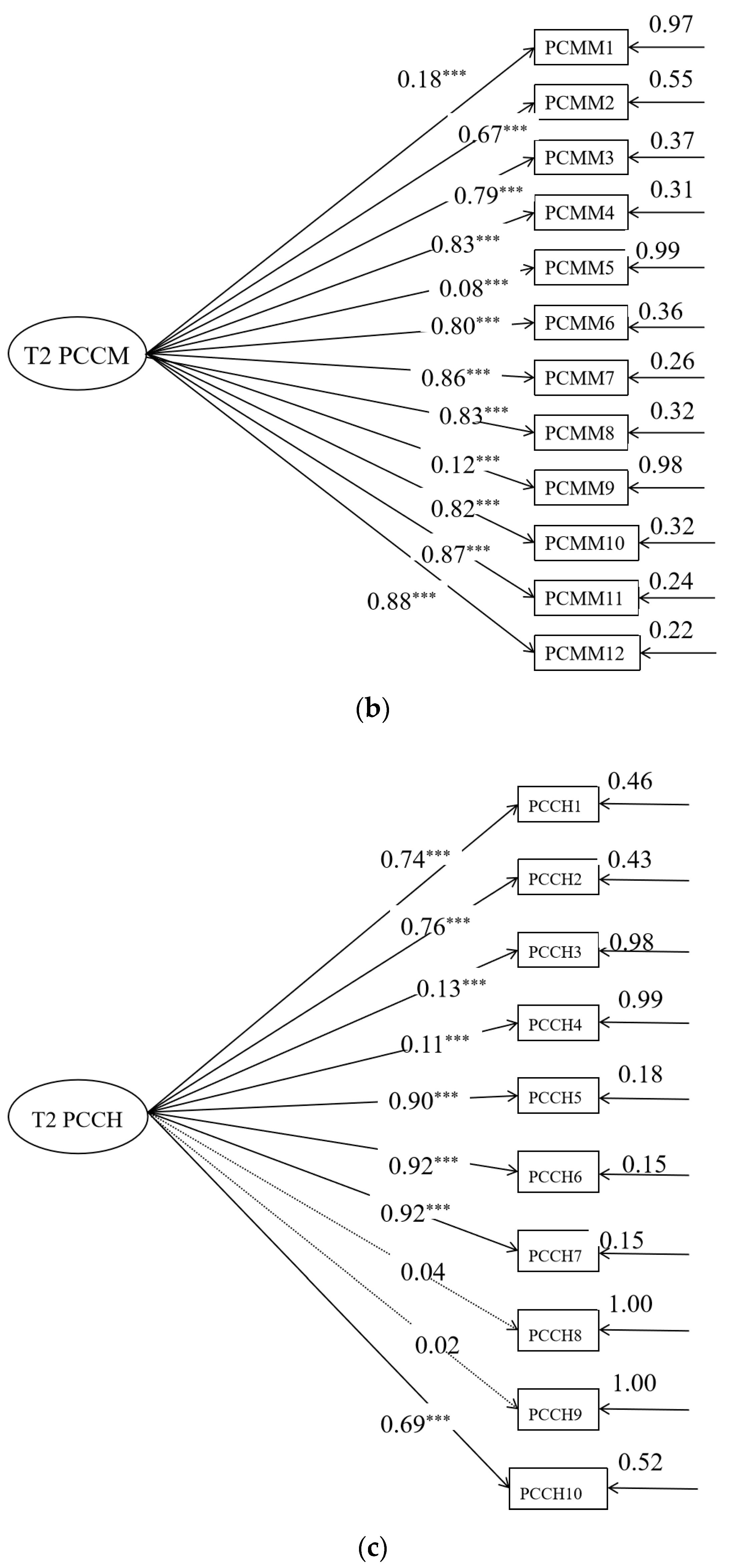

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Family Adaptation

2.2.2. Parental Autonomy Support

2.2.3. Parent–Child Communication

2.2.4. Parent–Child Cohesion

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Result

3.1. Common Method Bias

3.2. Description of Statistics and Comparison with the Current Situation

3.3. Related Analysis

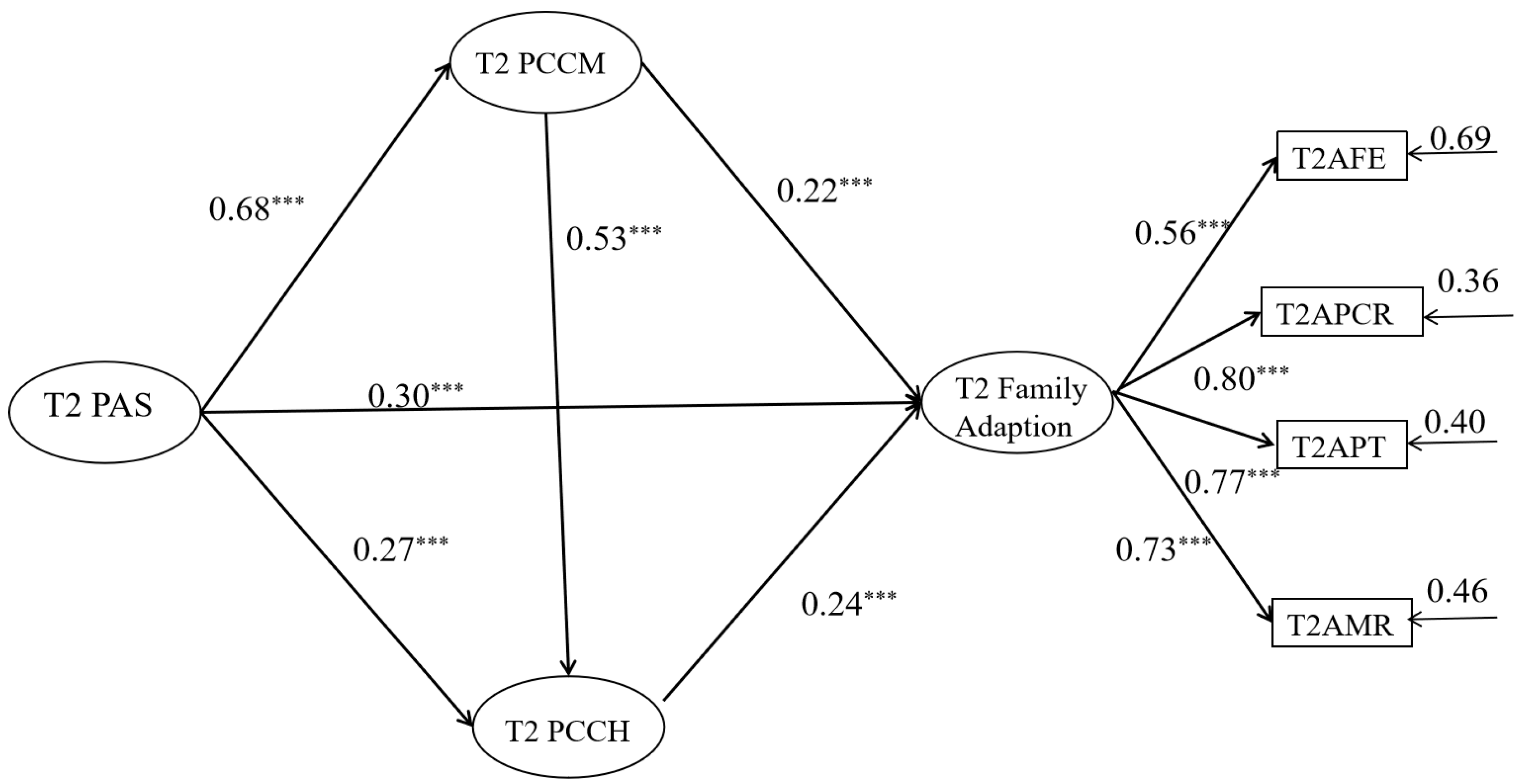

3.4. Intermediary Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Impact of Parental Autonomy Support on Family Adaptation

4.2. The Mediating Role of Parent–Child Communication

4.3. The Mediating Role of Parent–Child Cohesion

4.4. Chain Mediation of Parent–Child Communication and Parent–Child Cohesion

4.5. Limitations and Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jin, X.; Sun, Y. Does Double Reduction Policy decrease educational pressures on Chinese family? In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Education, Language and Art (ICELA 2021), Virtual, 26–28 November 2021; Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2022; pp. 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, J.M. Families experiencing stress: The family adjustment and adaptation response model: II. Applying the FAAR model to health-related issues for intervention and research. Fam. Syst. Med. 1988, 6, 202–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Yang, X.; Li, Q. Realistic predicament and its mitigation strategy in the collaborative governance of after-school service against the background of “Double Reduction” Policy. Theory Pract. Educ. 2024, 07, 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, B.K.; Stolz, H.E.; Olsen, J.A. Parental support, psychological control, and behavioral control: Assessing relevance across time, culture, and method. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child. 2005, 70, i-147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Chen, B.; Qu, Y.; Zhu, Y. Impacts of parental burnout on chinese youth’s mental health: The role of parents’ autonomy support and emotion regulation. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 1679–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, B.; Matte-Gagné, C.; Stack, D.M.; Serbin, L.A.; Ledingham, J.E.; Schwartzman, A.E. Risk and protective factors for autonomy-supportive and controlling parenting in high-risk families. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, A.B.; Schmidt, A.; Kramer, A.C.; Schmiedek, F. A little autonomy support goes a long way: Daily autonomy-supportive parenting, child well-being, parental need fulfillment, and change in child, family, and parent adjustment across the adaptation to the COVID-19 pandemic. Child Dev. 2021, 92, 1679–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, R.; Liu, M.; Fu, X.; Fan, Y. Current state of the “Double Reduction” Policy from the perspective of parents and related suggestions. Fam. Educ. 2023, 1, 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, D.H. Circumplex Model of marital and family systems. J. Fam. Ther. 2000, 22, 144–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixson, M.D. Models and perspectives of parent–child communication. In Parents, Children, and Communication; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013; pp. 43–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ochoa, G.M.; Lopez, E.E.; Emler, N.P. Adjustment problems in the family and school contexts, attitude towards authority, and violent behavior at school in adolescence. Adolescence 2007, 42, 779–794. [Google Scholar]

- Zapf, H.; Boettcher, J.; Haukeland, Y.; Orm, S.; Coslar, S.; Wiegand-Grefe, S.; Fjermestad, K. A systematic review of parent-child communication measures: Instruments and their psychometric properties. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2023, 26, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, H.; Liu, X. Loneliness, non-suicidal self-injury, and friendship quality among Chinese left-behind adolescents: The role of parent-child cohesion. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 271, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, D.H.; Sprenkle, D.H.; Russell, C.S. Circumplex model of marital and family system: I. Cohesion and adaptability dimensions, family types, and clinical applications. Fam. Process 1979, 18, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Moos, R.H.; Moos, B.S. Family Environment Scale Manual; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum, F.; Rosen, K.; Ujiie, T.; Uchida, N. Family systems theory, attachment theory, and culture. Fam. Process 2002, 41, 328–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, M.J.; Paley, B. Understanding families as systems. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2003, 12, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, L.P. A three-level model of parent-child communication: Theory, tools, and applications in primary school students. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2011, 27, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Farver, J.A.; Zhang, Z.; Zeng, Q.; Yu, L.; Cai, B. Mainland Chinese parenting styles and parent-child Interaction. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2005, 29, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, X.; Yang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, W.; Deater-Deckard, K. Parenting styles and parent–adolescent relationships: The mediating roles of behavioral autonomy and parental authority. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 418494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segrin, C.; Woszidlo, A.; Givertz, M.; Bauer, A.; Taylor Murphy, M. The association between overparenting, parent-child communication, and entitlement and adaptive traits in adult children. Fam. Relat. 2012, 61, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.F.; Yao, Z. Under the background of “Double Reduction,” parents’ educational anxiety and its resolution Path. J. Xinjiang Norm. Univ. Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2022, 43, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.P.; Li, P.H.; Xu, Y.Y. From increasing burden to enhancing strength: The functional transformation of family education in children’s knowledge education under the “Double Reduction” Policy. J. Guizhou Norm. Univ. 2022, 38, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, M. Parent-child cohesion, friend companionship and left-behind children’s emotional adaptation in rural China. Child. Abuse Negl. 2015, 48, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, J.M. Integrating family resilience and family stress theory. J. Marriage Fam. 2002, 64, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.I.; Cho, I.Y. Factors affecting parent health-promotion behavior in early childhood according to family cohesion: Focusing on the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2022, 62, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, X.W.; Wei, X.; Wang, M.P.; Chen, L.; Zhang, W.X. The relationship between parental education level and adolescent academic adaptation: The mediating role of parental upbringing and parent-child communication. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 2, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wei, X.; Ji, L.; Chen, L.; Deater-Deckard, K. Reconsidering parenting in Chinese culture: Subtypes, stability, and change of maternal parenting style during early adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 2017, 46, 1117–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, G.; Kanat-Maymon, Y.; Assor, A. The role of unconditional parental regard in autonomy-supportive parenting. J. Pers. 2016, 84, 716–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, S.; Weiser, D.A.; Fischer, J.L. Self-efficacy, Parent-child relationships, and academic performance: A comparison of European American and Asian American college students. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2016, 19, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloia, L.S. Parent-child relationship satisfaction: The influence of family communication orientations and relational maintenance behaviors. Fam. J. 2020, 28, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Li, M.Y.; Cui, X.L.; Gao, X.P.; Huang, L.Z. The impact of video time on interpersonal relationship problems in adolescents: The chain mediating role of parent child communication and parent child intimacy. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2023, 31, 688–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Ye, B.J.; Ni, L.Y.; Yang, Q. The impact of family intimacy on prosocial behavior among college students: A moderated mediating effect. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 28, 178–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Pomerantz, E.M.; Chen, H. The role of parents’ control in early adolescents’ psychological functioning: A longitudinal investigation in the United States and China. Child Dev. 2007, 78, 1592–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, W. A Research on parent-adolescent conflict and cohesion. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 30, 1196–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, M.S.; Bentler, P.M. Treatments of missing data: A monte carlo comparison of RBHDI, iterative stochastic regression imputation, and expectation-maximization. Struct. Equ. Model. 2000, 7, 319–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Y.F. The traditional “family matters” becomes an important “national matter” in the new era: How the whole society supports parents in promoting children’s healthy development under the background of “Double Reduction”. People’s Educ. 2021, 22, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, L.; Liu, X.; Tang, Y.; Yang, M.; Li, B. Parental psychological control, autonomous support and adolescent internet gaming disorder: The mediating role of impulsivity. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 29, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fousiani, K.; van Petegem, S.; Soenens, B.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Chen, B.W. Does parental autonomy support relate to adolescent autonomy? An in-depth examination of a seemingly simple question. J. Adolesc. Res. 2014, 29, 299–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. The Impact of Education on Income Inequality in China: Measurement and Decomposition. J. Shanghai Univ. Financ. Econ. 2021, 23, 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X.; Wang, C.; Shen, Z.; Fang, X. Associations of private tutoring with Chinese students’ academic achievement, emotional well-being, and parent-child relationship. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 112, 104934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bülow, A.; Neubauer, A.B.; Soenens, B.; Boele, S.; Denissen, J.J.; Keijsers, L. Universal ingredients to parenting teens: Parental warmth and autonomy support promote adolescent well-being in most families. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapetanovic, S.; Skoog, T. The role of the family’s emotional climate in the links between parent-adolescent communication and adolescent psychosocial functioning. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2021, 49, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marbell-Pierre, K.N.; Grolnick, W.S.; Stewart, A.L.; Raftery-Helmer, J.N. Parental autonomy support in two cultures: The moderating effects of adolescents’ self-construals. Child Dev. 2019, 90, 825–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Jiang, N.; Dou, J. Autonomy support and academic stress: A relationship mediated by self-regulated learning and mastery goal orientation. New Waves-Educ. Res. Dev. J. 2020, 23, 43–63. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Whitebread, D. Identifying characteristics of parental autonomy support and control in parent-child interactions. Early Child Dev. Care. 2021, 191, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCubbin, H.I.; Patterson, J.M. Family transitions: Adaptation to stress. In Stress and the Family; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 5–25. [Google Scholar]

- Widmer, E.D. Who are my family members? Bridging and binding social capital in family configurations. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 2006, 23, 979–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindblom, J. Significance of Early Family Environment on Children’s Affect Regulation: From Family Autonomy and Intimacy to Attentional Processes and Mental Health; Tampere University Press: Tampere, Finland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, Y.H. The relationship between family intimacy and adaptability, children’s educational control sources, and problem behaviors in children with autism. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 26, 78–81+85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.; Brody, G.H.; Miller, G.E. Childhood close family relationships and health. Am. Psychol. 2017, 72, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, B. Implement the “Double Reduction” Work and Deepen the Comprehensive Reform in the Field of Education. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xwfb/moe_2082/2021/2021_zl49/202107/t20210724_546578.html (accessed on 8 April 2024).

| Variables | Before “Double Reduction” (T1) | After “Double Reduction” (T2) | t |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parental Autonomy Support | 3.82 ± 0.55 | 3.85 ± 0.55 | −10.03 *** |

| AFE | 3.02 ± 0.41 | 3.02 ± 0.42 | −3.49 *** |

| APCR | 3.66 ± 0.44 | 3.69 ± 0.44 | −11.19 *** |

| APT | 3.40 ± 0.57 | 3.42 ± 0.58 | −8.37 *** |

| AMR | 3.61 ± 0.55 | 3.63 ± 0.56 | −9.52 *** |

| Family Adaptation | 3.36 ± 0.38 | 3.38 ± 0.39 | −9.95 *** |

| M ± SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. T1 PAS | 3.82 ± 0.55 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 2. T2 PAS | 3.85 ± 0.55 | 0.95 *** | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 3. T1 AFE | 3.02 ± 0.41 | 0.26 *** | 0.26 *** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 4. T1 APCR | 3.66 ± 0.44 | 0.53 *** | 0.52 *** | 0.40 *** | 1 | |||||||||||

| 5. T1 APT | 3.40 ± 0.57 | 0.39 *** | 0.39 *** | 0.51 *** | 0.60 *** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 6. T1 AMR | 3.61 ± 0.55 | 0.42 *** | 0.42 *** | 0.38 *** | 0.59 *** | 0.57 *** | 1 | |||||||||

| 7. T2 AFE | 3.02 ± 0.42 | 0.25 *** | 0.27 *** | 0.95 *** | 0.39 *** | 0.49 *** | 0.38 *** | 1 | ||||||||

| 8. T2 APCR | 3.69 ± 0.44 | 0.50 *** | 0.54 *** | 0.38 *** | 0.92 *** | 0.56 *** | 0.58 *** | 0.42 *** | 1 | |||||||

| 9. T2 APT | 3.42 ± 0.58 | 0.37 *** | 0.43 *** | 0.49 *** | 0.56 *** | 0.94 *** | 0.56 *** | 0.37 *** | 0.61 *** | 1 | ||||||

| 10. T2 AMR | 3.63 ± 0.56 | 0.40 *** | 0.44 *** | 0.37 *** | 0.57 *** | 0.55 *** | 0.97 *** | 0.42 *** | 0.60 *** | 0.58 *** | 1 | |||||

| 11. T2PCCM | 2.92 ± 0.41 | 0.58 *** | 0.61 *** | 0.40 *** | 0.56 *** | 0.47 *** | 0.49 *** | 0.52 *** | 0.59 *** | 0.49 *** | 0.51 *** | 1 | ||||

| 12. T2PCCH | 3.60 ± 0.57 | 0.44 *** | 0.46 *** | 0.36 *** | 0.52 *** | 0.43 *** | 0.48 *** | 0.40 *** | 0.54 *** | 0.45 *** | 0.49 *** | 0.67 *** | 1 | |||

| 13. Age | 43.202 ± 22.39 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.00 | 0.00 | −0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 1 | ||

| 14. Gender | / | 0.04 ** | 0.03 * | 0.10 *** | 0.05 *** | 0.05 *** | 0.01 | 0.08 *** | 0.03 * | 0.07 *** | 0.01 | 0.05 *** | 0.12 *** | −0.05 ** | 1 | |

| 15. SES | / | 0.17 *** | 0.18 *** | 0.22 *** | 0.18 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.21 *** | 0.17 *** | 0.27 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.17 *** | 0.12 *** | −0.03 | 0.06 *** | 1 |

| Effects | Model Pathways | Effect Value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Direct effect | T1 parental autonomy support → T2 family adaptation | 0.227 *** | 0.184 | 0.271 |

| Mediating effects | T1 parental autonomy support → T2 parent–child communication → T2 family adaptation | 0.168 *** | 0.134 | 0.198 |

| T1 parental autonomy support→T2 parent–child cohesion → T2 family adaptation | 0.066 *** | 0.054 | 0.082 | |

| T1 parental autonomy support → T2 parent–child communication → T2 parent–child cohesion → T2 family adaptation | 0.093 *** | 0.080 | 0.109 | |

| Total mediating effect | 0.327 *** | 0.299 | 0.356 | |

| Total effect | 0.554 *** | 0.521 | 0.584 | |

| Effects | Model Pathways | Effect Value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Direct effect | T2 parental autonomy support → T2 family adaptation | 0.303 *** | 0.259 | 0.341 |

| Mediating effects | T2 parental autonomy support → T2 parent–child communication → T1 family adaptation | 0.147 *** | 0.115 | 0.177 |

| T2 parental autonomy support → T1 parent–child cohesion → T1 family adaptation | 0.064 *** | 0.051 | 0.079 | |

| T2 parental autonomy support → T2 parent–child communication → T2 parent–child cohesion → T2 family adaptation | 0.086 *** | 0.072 | 0.102 | |

| Total mediating effect | 0.297 *** | 0.270 | 0.328 | |

| Total effect | 0.601 *** | 0.573 | 0.628 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xie, R.; Wang, X.; Ding, Y.; Chen, Y.; Ding, W. The Impact of Parental Autonomy Support on Family Adaptation in the Context of “Double Reduction”: The Mediating Role of Parent–Child Communication and Cohesion. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 534. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070534

Xie R, Wang X, Ding Y, Chen Y, Ding W. The Impact of Parental Autonomy Support on Family Adaptation in the Context of “Double Reduction”: The Mediating Role of Parent–Child Communication and Cohesion. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(7):534. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070534

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie, Ruibo, Xuan Wang, Yangguang Ding, Yanling Chen, and Wan Ding. 2024. "The Impact of Parental Autonomy Support on Family Adaptation in the Context of “Double Reduction”: The Mediating Role of Parent–Child Communication and Cohesion" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 7: 534. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070534

APA StyleXie, R., Wang, X., Ding, Y., Chen, Y., & Ding, W. (2024). The Impact of Parental Autonomy Support on Family Adaptation in the Context of “Double Reduction”: The Mediating Role of Parent–Child Communication and Cohesion. Behavioral Sciences, 14(7), 534. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070534