Trend Conformity Behavior of Luxury Fashion Products for Chinese Consumers in the Social Media Age: Drivers and Underlying Mechanisms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Social Influence Theory

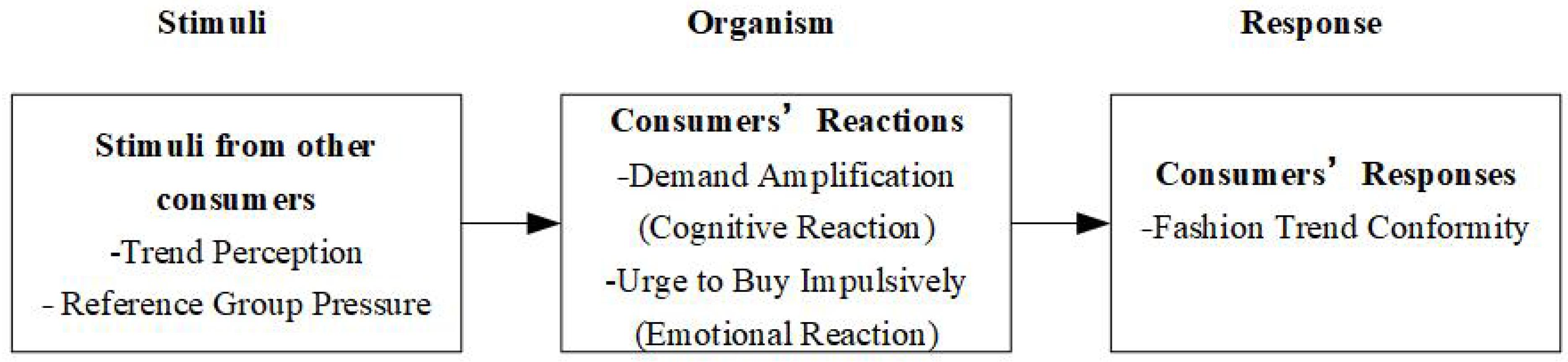

2.2. SOR Model and FOMO Model

3. Hypotheses Development

3.1. Fashion Trend Conformity

3.2. Trend Perception

3.3. Reference Group Pressure

3.4. Demand Amplification (Cognitive Reaction Path)

3.5. Urge to Buy Impulsively (Emotional Reaction Path)

4. Method

4.1. Measures

4.2. Samples and Data Collection

5. Data Analysis and Results

5.1. Measurement of Validity and Reliability

5.2. Hypothesis Tests

5.3. Mediating Effect Tests

6. Discussion and Implications

6.1. Discussion of Findings

6.2. Theoretical Implications

6.3. Managerial Implications

6.4. Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hati, S.R.H.; Kamarulzaman, Y.; Omar, N.A. Has the pandemic altered luxury consumption and marketing? A sectoral and thematic analysis. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2024, 48, e13013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T. A Comparative Analysis of Global Luxury Brands; Bruce, M., Moore, C., Birtwistle, G., Eds.; International retail marketing: Oxford, UK; Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- D’Arpizio, C.; Levato, F.; Prete, F.; Gault, C.; Montgolfier, J. Eight Themes That Are Rewriting the Future of Luxury Goods. 2019. Available online: https://www.bain.com/globalassets/noindex/2020/bain_digest_eight_themes_that_are_rewriting_the_future_of_luxury-goods.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2023).

- Sun, Y.; Wang, R.; Cao, D.M.; Lee, R. Who are social media influencers for luxury fashion consumption of the Chinese Gen Z? Categorisation and empirical examination. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2021, 26, 603–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannini, S.; Xu, Y.; Thomas, J. Luxury fashion consumption and generation Y consumers. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2015, 19, 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Kim, J. Luxury fashion consumption in China: Factors affecting attitude and purchase intent. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2013, 20, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latter, C.; Phau, I.; Marchegiani, C. The roles of consumers need for uniqueness and status consumption in haute couture luxury brands. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2010, 1, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Kuah, A.T.H.; Lu, Q.; Wang, C.; Thirumaran, K.; Adegbite, E.; Kendall, W. The impact of value perceptions on purchase intention of sustainable luxury brands in China and the UK. J. Brand Manag. 2021, 28, 325–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, S.; Lee, S.H.M. One size fits all? Segmenting consumers to predict sustainable fashion behavior. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2022, 26, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.K.; Kim, E.J.; Lee, S.M.; Lee, Y.K. Impact of susceptibility to global consumer culture on commitment and loyalty in botanic cosmetic brands. Sustainability 2021, 13, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Teng, L.; Poon, P.S. Susceptibility to global consumer culture: A three-dimensional scale. Psychol. Market. 2008, 25, 336–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potts, J. Fashionomics. Policy 2007, 23, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Eastman, J.; Lyer, R.; Shepherd, D.; Heugel, A.; Faulk, D. Do they shop to stand out or fit in? The luxury fashion purchase intentions of young adults. Psychol. Mark. 2018, 35, 220–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrad, M.; Majdalani, J.; Cui, C.C.; Khansa, Z.E. Brand addiction in the contexts of luxury and fast-fashion brands. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55, 102089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainolfi, G. Exploring materialistic bandwagon behaviour in online fashion consumption: A survey of Chinese luxury consumers. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 120, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastanakis, M.N.; Balabanis, G. Between the mass and the class: Antecedents of the ‘bandwagon’ luxury consumption behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1399–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibenstein, H. Bandwagon, snob, and veblen effects in the theory of conspicuous demand. Q. J. Econ. 1950, 64, 183–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, M.; Gerard, H.B. A study of normative and informational social influences upon individual judgment. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1955, 51, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Trost, M.R. Social Influence, Social Norms, Conformity and Compliance; Gilbert, D.T., Fiske, S.T., Lindzey, G., Eds.; Handbook of Social Psychology; McGraw-Hill: Boston, MA, USA, 1998; Volume 2, pp. 151–192. [Google Scholar]

- Das, M.; Habib, M.; Saha, V.; Jebarajakirthy, C. Bandwagon vs snob luxuries: Targeting consumers based on uniqueness dominance. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 61, 102582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, J.P.; Wheeler, L.; Suls, J. A social comparison theory meta-analysis 60+ years on. Psychol. Bull. 2018, 144, 177–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Festinger, L. A Theory of Social Comparison Processes. Hum. Relat. 1954, 7, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I.P.; Kausar, D.R.; Soesilo, P.K.M. The effect of engagement in online social network on susceptibility to influence. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2015, 42, 201–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangarkar, A.; Patel, J.; Kumar, S.K. Drivers of eWOM engagement on social media for luxury consumers Analysis, implications, and future research directions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 74, 103410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhang, J.; Xie, Z.; Niu, J. Online low-key conspicuous behavior of fashion luxury goods: The antecedents and its impact on consumer happiness. J. Consum. Behav. 2021, 20, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.J.; Ko, E. Do social media marketing activities enhance customer equity? An empirical study of luxury fashion brand. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1480–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.J.; Ko, E. Impacts of luxury fashion brand’s social media marketing on customer relationship and purchase intention. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2010, 1, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Watkins, B. Youtube vloggers’ influence on consumer luxury brand perceptions and intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5753–5760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Park, J.S. Influencer-brand fit and brand dilution in china’s luxury market: The moderating role of self-concept clarity. J. Brand Manag. 2021, 117, 520–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedmann, K.P.; Mettenheim, W.V. Attractiveness, trustworthiness and expertise—Social influencers’ winning formula? J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2021, 30, 707–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godey, B.; Manthiou, A.; Pederzoli, D.; Rokka, J.; Aiello, G.; Donvito, R.; Singh, R. Social media marketing efforts of luxury brands: Influence on brand equity and consumer behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5833–5841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, X.; Park, S.K.; Yang, Y. Rejections are more contagious than choice: How another’s decisions shape our own. J. Consum. Res. 2023, 50, 363–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; MIT: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, Y.F.; Chen, F.L. The effect of interactivity of brands’ marketing activities on Facebook fan pages on continuous participation intentions: A S–O-R framework study. J. Retailing Consum. Serv. 2023, 74, 103446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, A.; Murayama, K.; DeHaan, C.; Gladwell, V. Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 1841–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argan, M.; Argan, M.T.; Aydinoglu, N.Z.; Özer, A. The delicate balance of social influences on consumption A comprehensive model of consumer-centric fear of missing out. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2022, 194, 111638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, V.L. Situational factors in conformity. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1965, 2, 133–175. [Google Scholar]

- Breckler, S.J.; Olson, J.; Wiggins, E. Social Psychology Alive; Thomson/Wadsworth: Belmont, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jahoda, M. Conformity and independence. Hum. Relat. 1959, 12, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, E.; Wilson, T.D.; Akert, R.M. Social Psychology: Media and Research Update; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg, M.A.; Vaughan, G.M. Social Psychology; Pearson/Prentice Hall: Harlow, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mirre, S.; Sanfey, A.G. The neuroscience of social conformity: Implications for fundamental and applied research. Front. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 337. [Google Scholar]

- Çelen, B.; Kariv, S. Distinguishing informational cascades from herd behavior in the laboratory. Am. Econ. Rev. 2004, 94, 484–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Feinberg, R. E-formity: Consumer conformity behaviour in virtual communities. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2010, 4, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnkrant, R.E.; Alain, C. Informational and normative social influence in buyer behavior. J. Consum. Res. 1975, 2, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsay, H.H.; Lin, T.C.; Yoon, J.; Huang, C.C. Knowledge withholding intentions in teams: The roles of normative conformity, affective bonding, rational choice and social cognition. Decis. Support Syst. 2014, 6, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Yun, Z.S. Consumers’ perceptions of organic food attributes and cognitive and affective attitudes as determinants of their purchase intentions toward organic food. Food. Qual. Prefer. 2015, 39, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.; Levy, M.; Grewal, D. An experimental approach to making retail store environment decisions. J. Retail. 1992, 68, 445–460. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, V.A. Stimuli–organism-response framework: A meta-analytic review in the store environment. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1420–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, S.; Sarmah, B.; Gupta, S.; Dwivedi, Y. Examining branding cocreation in brand communities on social media: Applying the paradigm of stimulus-organism-response. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 39, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basha, N.K.; Aw, E.C.; Chuah, S.H. Are we so over smartwatches? Or can technology, fashion, and psychographic attributes sustain smartwatch usage? Technol. Soc. 2022, 69, 101952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Men, J.; Yang, F.; Gong, X. Understanding impulse buying in mobile commerce: An investigation into hedonic and utilitarian browsing. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 48, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, H. Veblen online: Information and the risk of commandeering the conspicuous self. Inf. Res. 2018, 23, 1368–1613. [Google Scholar]

- Song, G.; Ma, Q.; Wu, F.; Li, L. The psychological explanation of conformity. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2012, 40, 1365–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatty, S.E.; Ferrell, M.E. Impulse buying: Modeling its precursors. J. Retail. 1998, 74, 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, T.C.T.; Lee, Y. “I want to be as trendy as influencers”—How “fear of missing out” leads to buying intention for products endorsed by social media influencers. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 16, 346–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayran, C.; Anik, L.; Gurhan-Canli, Z. Exploring the antecedents and consumer behavioral consequences of “feeling of missing out (Fomo). In Creating Marketing Magic and Innovative Future Marketing Trends, Proceedings of the 2016 Academy of Marketing Science (AMS) Annual Conference, Orland, FL, USA, 20–21 May 2016; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Çelik, I.K.; Eru, O.; Cop, R. The effects of consumer FOMO tendencies on impulse buying and the effects of impulse buying on post-purchase regret: An investigation on retail stores. BRAIN-Broad Res. Artif. Intellect. Neurosci. 2019, 10, 124–138. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, I.; Cui, H.; Son, J. Conformity consumption behavior and FOMO. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Jimenez, F.R.; Cicala, J.E. Fear of missing out scale: A self-concept perspective. Psychol. Mark. 2020, 37, 1619–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, Y.; Paul, J.; Baber, R. Effect of online social media marketing efforts on customer response. J. Consum. Behav. 2022, 21, 554–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Shin, H.; Burns, A.C. Examining the impact of luxury brand’s social media marketing on customer engagement: Using big data analytics and natural language processing. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 125, 815–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, F.M. A new product growth model for consumer durables. Manag. Sci. 1969, 15, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, J.G.; Phalen, P.F. The Mass Audience: Rediscovering the Dominant Model; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sundar, S.S. The MAIN Model: A Heuristic Approach to Understanding Technology Effects on Credibility. In Digital Media, Youth, and Credibility; MacArthur Foundation Series on Digital Media and Learning; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sankar, S.; Gürhan-Canli, Z.; Vicki, M. Withholding consumption: A social dilemma perspective on consumer boycotts. J. Consum. Res. 2001, 28, 399–417. [Google Scholar]

- Bearden, W.O.; Etzel, M.J. Reference group influence on product and brand purchase decisions. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childers, T.; Akshay, R.R. The Influence of Familial and Peer-Based Reference Groups on Consumer Decisions. J. Consum. Res. 1992, 19, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaldoss, W.; Jain, S. Trading up: A strategic analysis of reference group effects. Mark. Sci. 2008, 27, 932–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiesler, C.A.; Kiesler, S.B. Conformity; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, C.; Berger, J.; Boven, L.V. Identifiable but not identical: Combining social identity and uniqueness motives in choice. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 39, 561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anspal, S. Non-parametric decomposition and the choice of reference group: A study of the gender wage gap in 15 OCED countries. Int. J. Manpow. 2015, 36, 1266–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trautmann-Lengsfeld, S.A.; Herrmann, C.S. EEG reveals an early influence of social conformity on visual processing in group pressure situations. Soc. Neurosci. 2013, 8, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.K.; de Fortuny, E.J. Influencer-generated reference groups. J. Consum. Res. 2022, 49, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Méndez, J.; Baute-Díaz, N. Influencer marketing in the promotion of tourist destinations: Mega, macro and micro-influencers. Curr. Issues Tour. 2024, 27, 1332–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangarkar, A.; Rathee, S. The role of conspicuity: Impact of social influencers on purchase decisions of luxury consumers. Int. J. Advert. 2023, 42, 1150–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabiran, E.; Farivar, S.; Wang, F.; Grant, G. Virtually human: Anthropomorphism in virtual infuencer marketing. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 79, 103797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlich, M. The Power of Virtual Influencers: Impact on Consumer Behaviour and Attitudes in the Age of AI. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlich, M. Micro-influencer marketing during the COVID-19 pandemic: New vistas or the end of an era? J. Digit. Soc. Media Mark. 2022, 9, 337–353. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.E.; Lloyd, S.; Cervellon, M.C. Narrative-transportation storylines in luxury brand advertising: Motivating consumer engagement. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, T.; Kitchen, P.J. Celebrity ambassador/celebrity endorsement—Takes a licking but keeps on ticking. J. Strateg. Mark. 2019, 27, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Choi, J.B.; Greene, M. Synergistic effects of social media and traditional marketing on brand sales: Capturing the time-varying effects. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 268–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaldoss, W.; Jain, S. Reference groups and product line decisions: An experimental investigation of limited editions and product proliferation. Manag. Sci. 2010, 56, 621–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Lu, Z. Analysis on Demand and Definition of Implicit Demand. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2006, 9, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, H.; Jo, S.H. The impact of age stereotype threats on older consumers’ intention to buy masstige brand products. Int. J. Consum Stud. 2024, 48, e12867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akoglu, H.E.; Yildiz, K.; Kumar, S. Why do athletes consume luxury brands? A study on motivations and values from the lens of theory of prestige consumption. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2024, 42, 879–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corneo, G.; Jeanne, O. Conspicuous consumption, snobbism and conformism. J. Public Econ. 1997, 66, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmashhara, M.G.; Blazquez, M.; Juliao, J. Stylish virtual tour: Exploring fashion’s influence on attitude and satisfaction in VR tourism. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2024; online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gierl, H.; Huettl, V. Are scarce products always more attractive? The interaction of different types of scarcity signals with products’ suitability for conspicuous consumption. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2010, 27, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Leary, M.R. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalas, J.E.; Bettman, J.R. Self-construal, reference groups, and brand meaning. J. Consum. Res. 2005, 32, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asch, S.E. Opinions and social pressure. Sci. Am. 1955, 193, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lana, J.; de Souza, M.J.B.; Lana, J.; Partyka, R.B. Tell me what you drink, I’ll tell you who You are: Status and fashion effects on consumer conformity. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2022, 28, 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, L.; Li, H.; Feng, H. Website attributes in urging online impulse purchase: An empirical investigation on consumer perceptions. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 55, 829–837. [Google Scholar]

- Piron, F. Defining impulse purchasing. Adv. Consum. Res. 1991, 18, 509–514. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y. Internet celebrities’ impact on luxury fashion impulse buying. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 2470–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamim, K.; Azam, M.; Islam, T. How do social media influencers induce the urge to buy impulsively? Social commerce context. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 77, 103621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Q.; Ko, E. Impulsive purchasing and luxury brand loyalty in Wechat mini program. Asia Pac. J. Market. Logist. 2021, 33, 2054–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiv, B.; Fedorikhin, A. Heart and mind in conflict: The interplay of affect and cognition in consumer decision making. J. Consum. Res. 1999, 26, 278–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, G.; Sivakumaran, B.; Sharma, P. Impact of store environment on impulse buying behavior. Eur. J. Market. 2013, 47, 1711–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroughi, A.; Nor, A.B.; Reyhane, H. Exploring the influence of situational factors (money and time available) on impulse buying behavior among different ethics. Int. J. Fund. Psychol. Soc. Sci. 2012, 2, 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- Zafar, A.U.; Qiu, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Shahzad, M. The impact of social media celebrities’ posts and contextual interactions on impulse buying in social commerce. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 115, 106178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z. How the characteristics of social media influencers and live content influence consumers’ impulsive buying in live streaming commerce? The role of congruence and attachment. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 506–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzallah, D.; Muñoz Leiva, F.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F. To buy or not to buy, that is the question: Understanding the determinants of the urge to buy impulsively on Instagram Commerce. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 16, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moes, A.; Fransen, M.; Fennis, B.; Verhagen, T.; van Vliet, H. In-store interactive advertising screens: The effect of interactivity on impulse buying explained by self-agency. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 16, 457–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shrum, L.J. What is interactivity and is it always such a good thing? Implications of definition, person, and situation for the influence of interactivity on advertising effectiveness. J. Advert. 2002, 31, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Liu, D. Product engagement and identity signaling: The role of likes in social commerce for fashion products. Inf. Manag. 2019, 56, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall-Phillips, A.; Park, J.; Chung, T.L.; Anaza, N.A.; Rathod, S.R. I (heart) social ventures: Identification and social media engagement. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivetz, R.; Zheng, Y. Determinants of justification and self-control. J. Exp. Psychol.-Gen. 2006, 135, 572–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y. The justification heuristic: A simple and efficient decision process for consumer to purchase or choose indulgence. J. Mark. Sci. 2007, 3, 63–71. [Google Scholar]

- Chaiken, S. The heuristic model of persuasion. In Social Influence; Zanna, M.P., Olson, J.M., Hermann, C.P., Eds.; The Ontario symposium; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Chow, S.; Celsi, R.L.; Abel, R. The effects of situational and intrinsic sources of personal relevance on brand choice decisions. Adv. Consum. Res. 1990, 17, 755–759. [Google Scholar]

- Quester, P.G.; Smart, J. The influence of consumption situation and product involvement over consumers’ use of product attribute. J. Consum. Mark. 1998, 15, 220–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, R.; Homer, P.; Kahle, L. Values, susceptibility to normative influence, and attribute importance weights: A nomological analysis. J. Consum. Psychol. 2001, 11, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnuerch, R.; Gibbons, H. A review of neurocognitive mechanisms of social conformity. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 45, 466–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Sivakumaran, B.; Marshall, R. Impulse buying and variety seeking: A trait-correlates perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Zhang, X. Impact of online consumer reviews on sales: The moderating role of product and consumer characteristics. J. Market. 2010, 74, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiit, E.M. Impact of voluntary sampling on estimates. Papers Anthropol. 2021, 30, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Anderson, R.; Tathan, R.; Black, W. Análisis Multivariante; Pearson: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, Y.; Choi, S.; Kim, H. Development and validation of an instrument to measure undergraduate students’ attitudes toward the ethics of artificial intelligence (AT-EAI) and analysis of its difference by gender and experience of AI education. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 11635–11667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall Upper: Saddle River, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric theory. Am. Educ. Res. J. 1978, 5, 678–685. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mick, D.; Demoss, M. Self-Gifts: Phenomenological Insights from Four Contexts. J. Consum. Res. 1990, 17, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Items | Question |

|---|---|---|

| Trend Perception (TP) | TP1 | I feel that many people have already purchased the luxury fashion product when seeing ubiquitous online conspicuous behaviors of buyers. |

| TP2 | The luxury fashion product tops the online sales charts, which displays a popular trend. | |

| TP3 | The lifestyle of the luxury fashion product is a leading trend on various social media platforms. | |

| TP4 | The luxury fashion product has absolutely consistent positive reviews. | |

| Reference Group Pressure (RGP) | RGP1 | People who I follow or care about have already purchased the luxury fashion product. |

| RGP2 | People who I follow or care about recommended the luxury fashion product via public and private digital channels. | |

| RGP3 | People who I follow or care about thought the luxury fashion product should be purchased to keep up with the newest fashion trend. | |

| RGP4 | People who I follow or care about have shared information of the luxury fashion product. | |

| RGP5 | Most of the people who I follow or care about have given the luxury fashion product positive reviews. | |

| Demand Amplification (DA) | DA1 | My implicit demand for the luxury fashion product is activated when seeing so many people buying it via various digital channels. |

| DA2 | My explicit demand for the luxury fashion product is enlarged when seeing so many people buying it via various digital channels. | |

| DA3 | I was not in a hurry to buy the luxury fashion product, but now I can’t wait to buy it when seeing so many people buying it via various digital channels. | |

| DA4 | I thought the luxury fashion product was a bit expensive, but now I suddenly feel that it is not that expensive anymore when seeing so many people buying it via various digital channels. | |

| Urge to Buy Impulsively (UBI) | UBI1 | I had the sudden urge to purchase the luxury fashion product outside my shopping list. |

| UBI2 | I experienced a number of sudden urges to buy the luxury fashion product I had not planned to purchase. | |

| UBI3 | I had the inclination to buy the luxury fashion product although I know that it is outside my shopping goal. | |

| UBI4 | I thought the luxury fashion product was ordinary, but suddenly I thought it was very good. | |

| Fashion trend conformity (FTC) | FTC1 | I bought the luxury fashion product that firmly made me feel good in my social group. |

| FTC2 | I bought the luxury fashion product that firmly gave me the sense of fashionable and stylish belonging. | |

| FTC3 | I bought the luxury fashion product that firmly causes me to make a good impression on others. | |

| FTC4 | I bought the luxury fashion product that firmly makes me feel a part of the fashion trend. |

| Variable | Item Number | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trend perception | 4 | 0.848 | 0.846 | 0.581 |

| Reference group pressure | 5 | 0.880 | 0.890 | 0.669 |

| Urge to buy impulsively | 4 | 0.843 | 0.838 | 0.567 |

| Demand amplification | 4 | 0.878 | 0.877 | 0.641 |

| Fashion trend conformity | 4 | 0.865 | 0.861 | 0.609 |

| Variable | Trend Perception | Reference Group Pressure | UBI | Demand Amplification | Fashion Trend Conformity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trend perception | 0.762 | ||||

| Reference group pressure | 0.456 | 0.818 | |||

| Urge to buy impulsively | 0.272 | 0.255 | 0.753 | ||

| Demand amplification | 0.310 | 0.458 | 0.520 | 0.801 | |

| Fashion trend conformity | 0.375 | 0.452 | 0.370 | 0.690 | 0.780 |

| Construct Relation | Standardized Path Coefficient | S.E. | C.R. | p | Hypothesis Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP → FTC | 0.119 * | 0.090 | 2.096 | 0.036 | H1 holds |

| RGP → FTC | 0.148 * | 0.073 | 2.471 | 0.013 | H2 holds |

| DA → FTC | 0.611 *** | 0.066 | 8.221 | 0.001 | H3 holds |

| TP → DA | 0.140 * | 0.125 | 1.986 | 0.047 | H4 holds |

| RGP → DA | 0.441 *** | 0.101 | 6.010 | 0.001 | H5 holds |

| TP → UBI | 0.186 ** | 0.088 | 2.618 | 0.009 | H7 holds |

| RGP → UBI | −0.095 | 0.071 | −1.289 | 0.197 | H8 not hold |

| DA → UBI | 0.567 *** | 0.057 | 6.952 | 0.001 | H9 holds |

| UBI → FTC | 0.055 | 0.080 | 0.875 | 0.381 | H6 not hold |

| Model Fitting Metrics | Χ2/df = 1.355; RMSEA = 0.034; GFI = 0.941; AGFI = 0.915; CFI = 0.986; TLI = 0.982; NFI = 0.949 | ||||

| Effect of TP on FTC | |||||

| Effect | SE | LLCI | ULCI | ||

| Indirect effect | TP→DA→FTC | 0.2275 | 0.0446 | 0.1425 | 0.3171 |

| TP→UBI→FTC | −0.0036 | 0.0170 | −0.0384 | 0.0294 | |

| Direct effect | TP→FTC | 0.2058 | 0.0476 | 0.1121 | 0.2995 |

| Total effect | TP→FTC | 0.4297 | 0.0589 | 0.3138 | 0.5456 |

| Effect of RGP on FTC | |||||

| Effect | SE | LLCI | ULCI | ||

| Indirect effect | RGP→DA→FTC | 0.2787 | 0.0396 | 0.2054 | 0.3585 |

| RGP→UBI→FTC | 0.0030 | 0.0137 | −0.0246 | 0.0311 | |

| Direct effect | RGP→FTC | 0.1733 | 0.0445 | 0.0858 | 0.2607 |

| Total effect | RGP→FTC | 0.4550 | 0.0497 | 0.3573 | 0.5527 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Zhuang, J. Trend Conformity Behavior of Luxury Fashion Products for Chinese Consumers in the Social Media Age: Drivers and Underlying Mechanisms. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 521. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070521

Chen Y, Zhuang J. Trend Conformity Behavior of Luxury Fashion Products for Chinese Consumers in the Social Media Age: Drivers and Underlying Mechanisms. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(7):521. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070521

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Ye, and Jingyi Zhuang. 2024. "Trend Conformity Behavior of Luxury Fashion Products for Chinese Consumers in the Social Media Age: Drivers and Underlying Mechanisms" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 7: 521. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070521

APA StyleChen, Y., & Zhuang, J. (2024). Trend Conformity Behavior of Luxury Fashion Products for Chinese Consumers in the Social Media Age: Drivers and Underlying Mechanisms. Behavioral Sciences, 14(7), 521. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070521