Exploring the Relationship between Maternal Gatekeeping with Paternal Parenting and Adolescent Aggression

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Parenting Styles and Adolescent Aggression

1.2. The Mutual Influence of Parenting between Parents

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

2.2. Self-Reported Measurements

2.2.1. Maternal Gatekeeping Behavior Perception Questionnaire

2.2.2. Adolescent Evaluation of Parental Involvement Behavior Questionnaire

2.2.3. Short Form of Parental Rearing Style Questionnaire

2.2.4. Buss and Perry Aggression Questionnaire

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Common Method Bias

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

3.2. Latent Profile Analysis

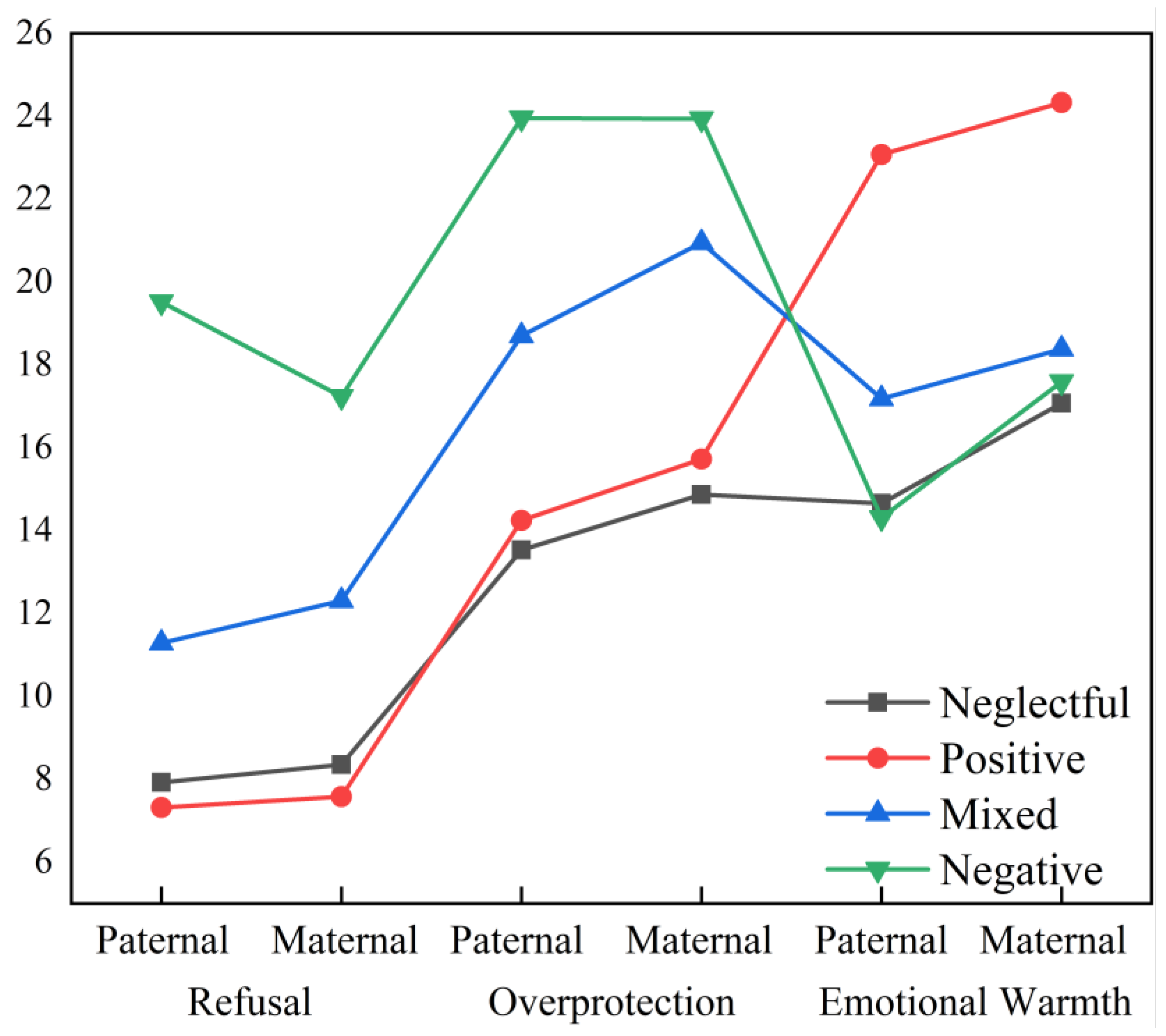

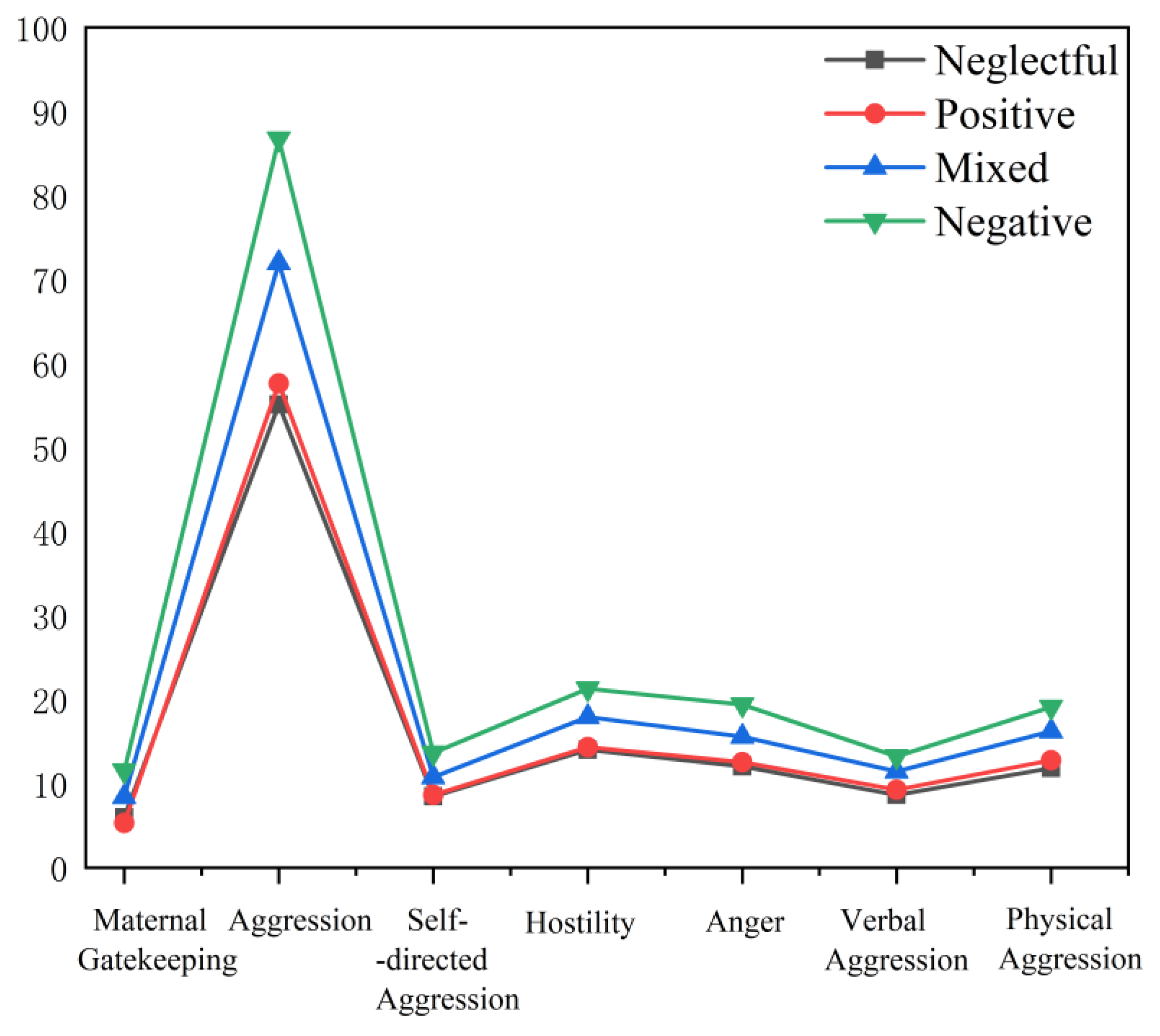

3.3. Validity of the Latent Profile Analysis Results

3.4. Correlation Analysis

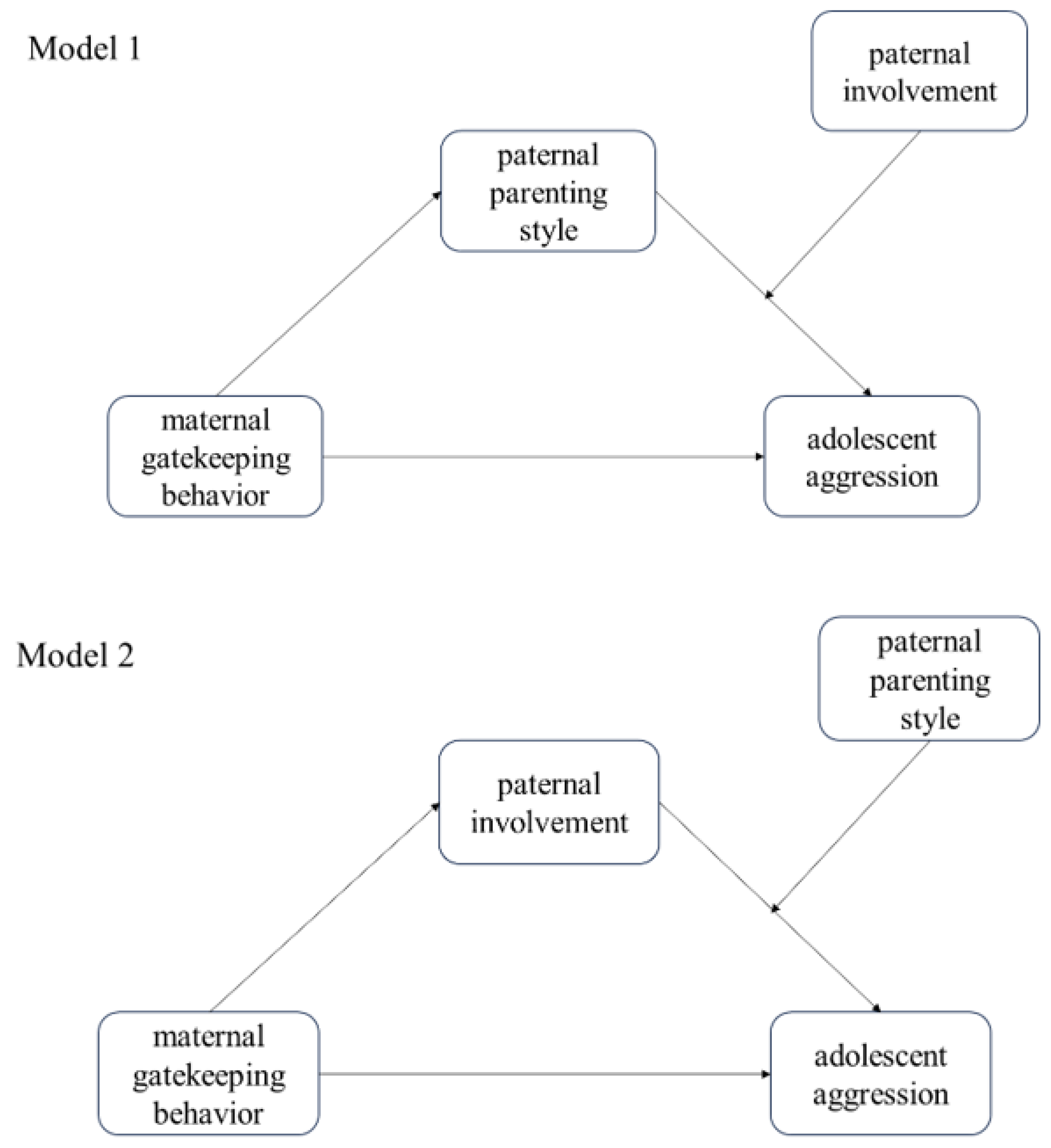

3.5. Moderated Mediation Model

4. Discussion

4.1. The Difference between Different Classifications of Pareting Styles

4.2. The Relationship between Maternal Gatekeeping and Paternal Parenting and Adolescent Aggressive Behavior

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Song, M.; Chen, C.; Liu, S.; Li, J.; Hou, Y.; Zhang, L. Effects of parenting styles on aggression of junior school students: Roles of deviant peer affiliation and self-control. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2017, 33, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felitti, V.J.; Anda, R.F.; Nordenberg, D.; Williamson, D.F.; Spitz, A.M.; Edwards, V.; Koss, M.P.; Marks, J.S. Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998, 14, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidal, S.; Rockville, W.; Connell, C.M. Treatment effects of parent-child focused evidence-based programs on problem severity and functioning among children and adolescents with disruptive behavior. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2019, 48, S326–S336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braza, P.; Carreras, R.; Muñoz, J.M.; Braza, F.; Azurmendi, A.; Pascual-Sagastizábal, E.; Cardas, J.; Sánchez-Martín, J.R. Negative Maternal and Paternal Parenting Styles as Predictors of Children’s Behavioral Problems: Moderating Effects of the Child’s Sex. J. Child. Fam. Stud. 2015, 24, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, J.F.; Weigel, S.M.; Crick, N.R.; Ostrov, J.M.; Woods, K.E.; Yeh, E.A.J.; Huddleston-Casas, C.A. Early parenting and children’s relational and physical aggression in the preschool and home contexts. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2006, 27, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumrind, D. Current Patterns of Parental Authority. Dev. Psychol. 1971, 4, 1–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.; Liu, Z.; Jang, Z.; Xu, Y. Revision of the Short-form Egna Minnen av Barndoms Uppfostran for Chinese, s-EMBU-C. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2010, 26, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y. The effect of parental rejection on aggressive behavior in left-behind children: A moderated mediated model. J. Guizhou Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2022, 40, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Guo, M.; Chang, S. The Association between Parental Rejection and Peer Rejection among Children: The Mediating Role of Problem Behaviors and the Moderating Role of Home Chaos. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2021, 37, 845–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, W. The Bidirectional Associations between Parental Rejection and Externalizing Problems among Chinese Adolescents. Chin. J. Appl. Psychol. 2022, 28, 125–133. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.; Kim, H.; Lee, D. Application of Social Control Theory to Examine Parent, Teacher, and Close Friend Attachment and Substance Use Initiation among Korean Youth. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2016, 37, 340–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeve, M.; Dubas, J.S.; Eichelsheim, V.I.; Van Der Laan, P.H.; Smeenk, W.; Gerris, J.R.M. The Relationship Between Parenting and Delinquency: A Meta-analysis. J. Abnorm. Child. Psychol. 2009, 37, 749–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, H.-J.; Cui, M.; Blair, B.L. The Mediating Roles of Adolescent Disclosure and Parental Knowledge in the Association Between Parental Warmth and Delinquency Among Korean Adolescents. J. Child. Fam. Stud. 2016, 25, 2395–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Guo, L.; Guo, L.; Guo, Y. Association of family functioning and parental styles with anxiety symptoms among high-grade primary school students. Chin. J. Sch. Health 2024, 45, 394–397+401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, S.; Wu, X.; Liu, C. The effect of Maternal Gatekeeping: Concept, theory and prospective. J. Beijing Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2016, 6, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, S.M.; Hawkins, A.J. Maternal Gatekeeping: Mothers’ Beliefs and Behaviors That Inhibit Greater Father Involvement in Family Work. J. Marriage Fam. 1999, 61, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLuccie, M.F. Mothers as Gatekeepers: A Model of Maternal Mediators of Father Involvement. J. Genet. Psychol. 1995, 156, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagan, J.; Cherson, M. Maternal Gatekeeping: The Associations Among Facilitation, Encouragement, and Low-Income Fathers’ Engagement with Young Children. J. Fam. Issues 2017, 38, 633–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, B.A.; Brown, G.L.; Bost, K.K.; Shin, N.; Vaughn, B.; Korth, B. Paternal Identity, Maternal Gatekeeping, and Father Involvement. Fam. Relat. 2005, 54, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Chen, L.; Liu, C.; Xing, X. The Characteristics of Father Involvement and Its Related Influencing Factors. J. South China Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2014, 6, 88–95. [Google Scholar]

- Rane, T.R.; McBride, B.A. Identity Theory as a Guide to Understanding Fathers’ Involvement with Their Children. J. Fam. Issues 2000, 21, 347–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Haslam, D.; Dittman, C.; Guo, M. The Effect of Parental Beliefs and Maternal Gatekeeping Behavior on Paternal Involvement in Parenting; Chinese Psychological Society: Beijing, China, 2018; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.; Wu, X.; Huang, B. Maternal Gatekeeping Behavior and Father-Adolescent Attachment: The Mediating Role of Father Involvement. J. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 42, 1361–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagan, J.; Barnett, M. The Relationship between Maternal Gatekeeping, Paternal Competence, Mothers’ Attitudes about the Father Role, and Father Involvement. J. Fam. Issues 2003, 24, 1020–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altenburger, L.E.; Schoppe-Sullivan, S.J.; Kamp Dush, C.M. Associations Between Maternal Gatekeeping and Fathers’ Parenting Quality. J. Child. Fam. Stud. 2018, 27, 2678–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvara, B.J.; Roger Mills-Koonce, W.; Cox, M. Family Life Project Key Contributors Intimate Partner Violence, Maternal Gatekeeping, and Child Conduct Problems. Fam. Relat. 2016, 65, 647–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, M.R.; Kim, M.J.; Yee, B.S. The Relationship Between Maternal Gatekeeping and Paternal Parenting: The Mediating Effects of Marital Communication. Korean J. Childcare Educ. 2015, 11, 355–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gaunt, R. Maternal Gatekeeping: Antecedents and Consequences. J. Fam. Issues 2008, 29, 373–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Cao, H.; Lin, C.; Ye, P. Family Socio-Economic Status and Chinese Preschoolers’ Anxious Symptoms during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Roles of Parental Investment, Parenting Style, Home Quarantine Length, and Regional Pandemic Risk. Early Child. Res. Q. 2022, 60, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, S. Development of Subjective Socioeconomic Status Scale for Chinese Adolescents. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 20, 155–161. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Liu, C.; Zhou, S.; Hou, F. Psychometric Properties of the Adolescence Revision of Paternal Involvement Behavior Questionnaire. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 26, 647–651. [Google Scholar]

- Arrindell, W.A.; Sanavio, E.; Aguilar, G.; Sica, C.; Hatzichristou, C.; Eisemann, M.; Recinos, L.A.; Gaszner, P.; Peter, M.; Battagliese, G.; et al. The development of a short form of the EMBU1: Its appraisal with students in Greece, Guatemala, Hungary and Italy. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1999, 27, 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Fei, L.; Zhang, Y.; Niu, Y.; Tong, Y.; Yang, S. Development, Reliability and Validity of the Chinese version of Buss & Perry Aggression Questionnaire. Chin. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2011, 37, 607–613. [Google Scholar]

- Burnham, K.P.; Anderson, D.R. Multimodel Inference: Understanding AIC and BIC in Model Selection. Sociol. Methods Res. 2004, 33, 261–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nylund, K.L.; Asparouhov, T.; Muthén, B.O. Deciding on the Number of Classes in Latent Class Analysis and Growth Mixture Modeling: A Monte Carlo Simulation Study. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2007, 14, 535–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T.; Wickrama, K.A.S. An Introduction to Latent Class Growth Analysis and Growth Mixture Modeling. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2008, 2, 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Chen, F.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, Y. Profiles of Maternal and Paternal Parenting Styles in Chinese Families: Relations to Preschoolers’ Psychological Adjustment. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 121, 105787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deal, J.E.; Wampler, K.S.; Halverson, C.F. The Importance of Similarity in the Marital Relationship. Fam. Process 1992, 31, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botwin, M.D.; Buss, D.M.; Shackelford, T.K. Personality and Mate Preferences: Five Factors in Mate Selection and Marital Satisfaction. J. Pers. 1997, 65, 107–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanz, M.; Scabini, E.; Vermulst, A.A.; Gerris, J.R.M. Congruence on Child Rearing in Families with early Adolescent and Middle Adolescent Children. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2001, 25, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maat, D.A.; Jansen, P.W.; Prinzie, P.; Keizer, R.; Franken, I.H.A.; Lucassen, N. Examining Longitudinal Relations Between Mothers’ and Fathers’ Parenting Stress, Parenting Behaviors, and Adolescents’ Behavior Problems. J. Child. Fam. Stud. 2021, 30, 771–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-García, D.; García, T.; Núñez, J.C. Predictors of School Bullying Perpetration in Adolescence: A Systematic Review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2015, 23, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marçal, K.E. Pathways to Adolescent Emotional and Behavioral Problems: An Examination of Maternal Depression and Harsh Parenting. Child. Abus. Negl. 2021, 113, 104917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özdemir, Y.; Vazsonyi, A.T.; Çok, F. Parenting Processes, Self-Esteem, and Aggression: A Mediation Model. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2017, 14, 509–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G. Researches on the Relationships Among Parental Rearing Style, Self-esteem and Aggression in College Students. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 16, 198–199. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, T.; Liu, J.; Gu, H.; Tong, S. The Effect of Interparental Conflicts on Adolescents’ Aggressive Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Model. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2016, 32, 503–512. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Wang, X. Interparental Conflict and Aggressive Behavior: The Mediating Effect of the Moral Disengagement. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2011, 27, 498–505. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Zhang, G.; Ma, Z. The Effect of Inter-parental Conflict on Aggression of Junior Middle School Student: The Chain Mediating Role of Regulatory Emotional Self-Efficacy and Emotional Insecurity. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 28, 1038–1041+1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Aggression: A Social Learning Analysis. Stanf. Law. Rev. 1973, 26, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ma, X.; Zhang, Y. Intergenerational transmission of aggression: A meta-analysis of relationship between interparental conflict and aggressive behavior of children and youth. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 32008–32023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J. Parental Monitoring and Left-behind-children’s Antisocial Behavior and Loneliness. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 21, 500–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.A.; Bushman, B.J. Human aggression. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2002, 53, 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McShane, K.E.; Hastings, P.D. The New Friends Vignettes: Measuring parental psychological control that confers risk for anxious adjustment in preschoolers. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2009, 33, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, L. Frustrations, Appraisals, and Aversively Stimulated Aggression. Aggress. Behav. 1988, 14, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubeva, E.; Istratova, O. Study of Frustration in Children Emotionally Rejected by Their Parents. Espacios 2018, 39, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Gracia, E.; Lila, M.; Musitu, G. Parental Rejection and Psychosocial Adjustment of Children. Salud Ment. 2005, 28, 73–81. [Google Scholar]

- Khaleque, A.; Rohner, R.P. Transnational Relations Between Perceived Parental Acceptance and Personality Dispositions of Children and Adults: A Meta-Analytic Review. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 16, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnellan, M.B.; Trzesniewski, K.H.; Robins, R.W.; Moffitt, T.E.; Caspi, A. Low Self-Esteem Is Related to Aggression, Antisocial Behavior, and Delinquency. Psychol. Sci. 2005, 16, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudolph, K.D.; Abaied, J.L.; Flynn, M.; Sugimura, N.; Agoston, A.M. Developing Relationships, Being Cool, and Not Looking Like a Loser: Social Goal Orientation Predicts Children’s Responses to Peer Aggression. Child. Dev. 2011, 82, 1518–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altenburger, L.E. Similarities and Differences between Coparenting and Parental Gatekeeping: Implications for Father Involvement Research. J. Fam. Stud. 2023, 29, 1403–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, Y.; Richards, L.N.; Zvonkovic, A.M. Are Mothers Really “Gatekeepers” of Children?: Rural Mothers’ Perceptions of Nonresident Fathers’ Involvement in Low-Income Families. J. Fam. Issues 2008, 29, 1701–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoppe-Sullivan, S.J.; Altenburger, L.E.; Lee, M.A.; Bower, D.J.; Kamp Dush, C.M. Who Are the Gatekeepers? Predictors of Maternal Gatekeeping. Parenting 2015, 15, 166–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulik, L.; Tsoref, H. The Entrance to the Maternal Garden: Environmental and Personal Variables that Explain Maternal Gatekeeping. J. Gend. Stud. 2010, 19, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sameroff, A.J.; Fiese, B.H. Transactional Regulation: The Developmental Ecology of Early Intervention. In Handbook of Early Childhood Intervention; Shonkoff, J.P., Meisels, S.J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; pp. 135–159. ISBN 978-0-521-58573-6. [Google Scholar]

- Wittig, S.M.O.; Rodriguez, C.M. Interaction between Maternal and Paternal Parenting Styles with Infant Temperament in Emerging Behavior Problems. Infant. Behav. Dev. 2019, 57, 101323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridgett, D.J.; Gartstein, M.A.; Putnam, S.P.; McKay, T.; Iddins, E.; Robertson, C.; Ramsay, K.; Rittmueller, A. Maternal and Contextual Influences and the Effect of Temperament Development during infancy on Parenting in Toddlerhood. Infant. Behav. Dev. 2009, 32, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.H.; Zhou, Q.; Eisenberg, N.; Wang, Y. Bidirectional Relations between Temperament and Parenting Styles in Chinese Children. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2013, 37, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lengua, L.J.; Kovacs, E.A. Bidirectional Associations between Temperament and Parenting and the Prediction of Adjustment Problems in Middle Childhood. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2005, 26, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuele, S.J.; Yap, M.B.H.; Lin, S.C.; Pozzi, E.; Whittle, S. Associations between Paternal versus Maternal Parenting Behaviors and Child and Adolescent Internalizing Problems: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2023, 105, 102339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Conventional Family Structure (N = 419) | Non-Conventional Family Structure (N = 64) | t/X2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| Age | 12.66 (0.82) | 12.66 (0.55) | 0.03 | 0.98 |

| Sex (M/F) | 213/206 | 36/28 | 0.35 | 0.58 |

| Maternal education | 2.04 (0.78) | 2.13 (0.98) | −0.79 | 0.43 |

| Paternal education | 2.17 (0.77) | 2.17 (0.92) | 0.06 | 0.95 |

| SES | 6.97(1.54) | 6.30 ± 1.56 | 3.27 | 0.00 |

| Maternal gate closing | 6.15 (5.07) | 9.16 (6.55) | −3.37 | 0.00 |

| Maternal gate opening | 13.08 (5.37) | 8.25 (6.63) | 5.31 | 0.00 |

| Maternal warmth | 21.24 (4.70) | 18.95 (6.22) | 2.70 | 0.01 |

| Maternal refusal | 9.23 (3.49) | 10.41 (4.57) | −1.97 | 0.05 |

| Maternal overprotection | 17.11 (4.52) | 17.33 (4.39) | −0.36 | 0.72 |

| Paternal involvement | 48.14 (18.33) | 33.72 (22.69) | 4.63 | 0.00 |

| Paternal warmth | 19.78 (5.05) | 15.45 (6.54) | 4.84 | 0.00 |

| Paternal refusal | 9.00 (3.61) | 9.84 (4.96) | −1.29 | 0.20 |

| Paternal overprotection | 15.68 (4.19) | 15.41 (4.11) | 0.47 | 0.64 |

| AQ_Total | 60.90 (20.13) | 66.71 (24.18) | −2.00 | 0.05 |

| Model | AIC | BIC | ABIC | Entropy | LMRLR (p) | BLRT (p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 23,085.336 | 23,143.885 | 23,099.450 | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| 2 | 22,263.725 | 22,355.731 | 22,285.905 | 0.917 | 0.0013 | <0.0001 |

| 3 | 21,948.334 | 22,073.797 | 21,978.579 | 0.882 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| 4 | 21,800.252 | 21,959.171 | 21,838.562 | 0.837 | 0.277 | <0.0001 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 AQ_total | 1 | |||||||

| 2 Paternal warmth | −0.105 * | 1 | ||||||

| 3 Paternal refusal | 0.398 ** | −0.389 ** | 1 | |||||

| 4 Paternal overprotection | 0.414 ** | −0.151 ** | 0.650 ** | 1 | ||||

| 5 Paternal involvement | −0.113 * | 0.695 ** | −0.263 ** | −0.040 | 1 | |||

| 6 Maternal warmth | −0.069 | 0.730 ** | −0.264 ** | −0.162 ** | 0.443 ** | 1 | ||

| 7 Maternal refusal | 0.435 ** | −0.292 ** | 0.708 ** | 0.525 ** | −0.230 ** | −0.402 ** | 1 | |

| 8 Maternal overprotection | 0.412 ** | −0.118 ** | 0.482 ** | 0.753 ** | −0.029 | −0.197 ** | 0.618 ** | 1 |

| 9 Maternal gate closing | 0.274 ** | −0.171 ** | 0.335 ** | 0.265 ** | −0.185 ** | −0.079 | 0.359 ** | 0.312 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, H.; Xu, P.; Jiang, Y. Exploring the Relationship between Maternal Gatekeeping with Paternal Parenting and Adolescent Aggression. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 517. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070517

Wang H, Xu P, Jiang Y. Exploring the Relationship between Maternal Gatekeeping with Paternal Parenting and Adolescent Aggression. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(7):517. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070517

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Huaiyu, Peijing Xu, and Yali Jiang. 2024. "Exploring the Relationship between Maternal Gatekeeping with Paternal Parenting and Adolescent Aggression" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 7: 517. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070517

APA StyleWang, H., Xu, P., & Jiang, Y. (2024). Exploring the Relationship between Maternal Gatekeeping with Paternal Parenting and Adolescent Aggression. Behavioral Sciences, 14(7), 517. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070517