Factors Influencing Willingness to Continue Using Online Sports Videos: Expansion Based on ECT and TPB Theoretical Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

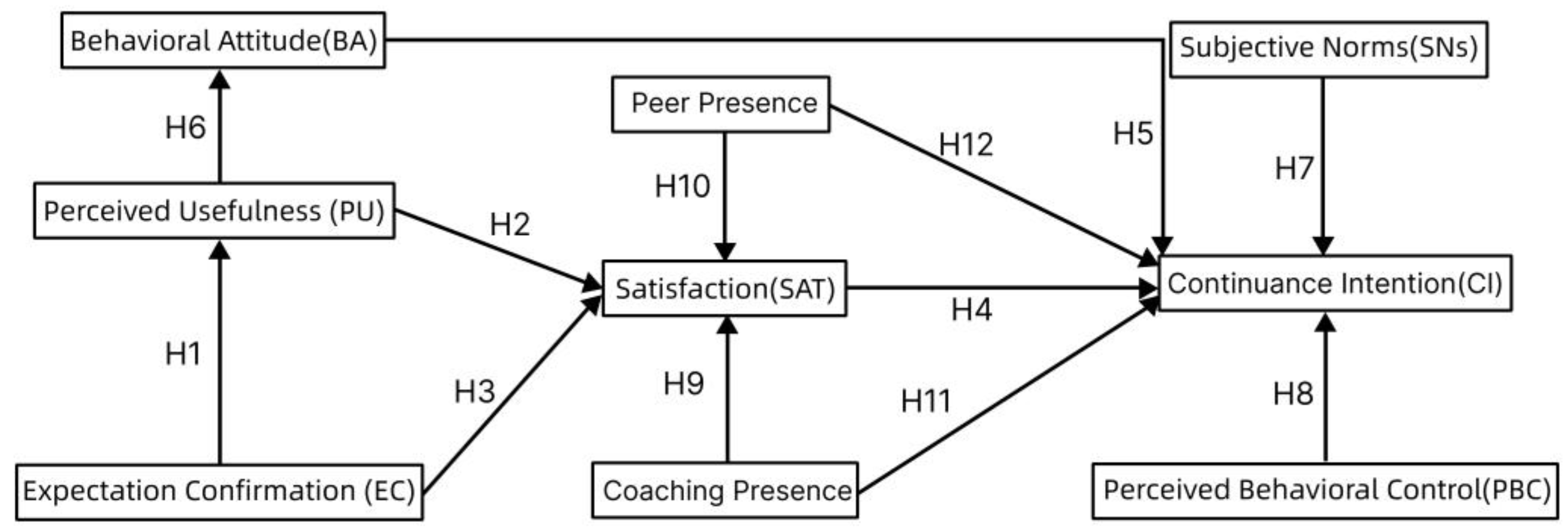

2. Research Modeling

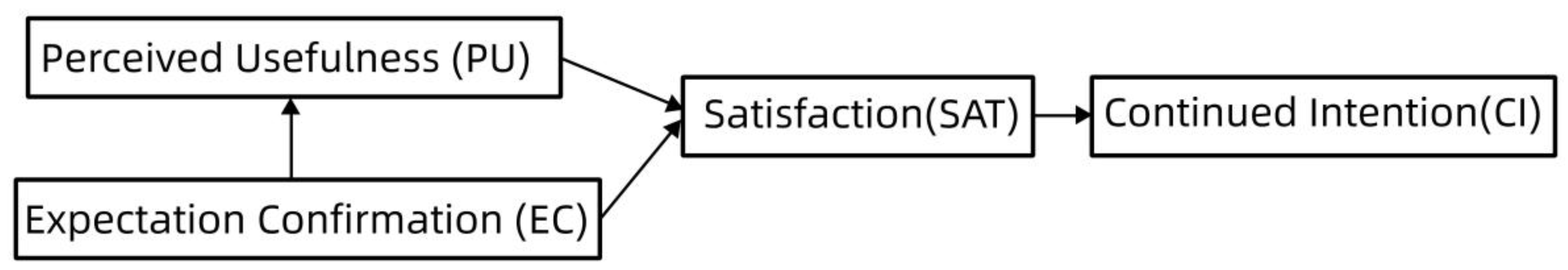

2.1. Expectation-Confirmation Theory

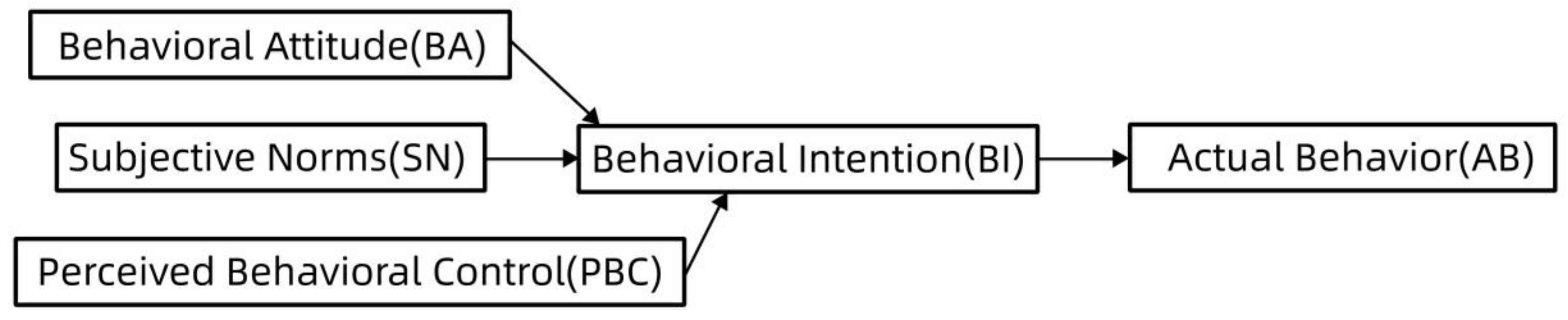

2.2. Theory of Planned Behavior

2.3. Social Presence: Coach and Peer Social Presence

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

3.2. Measurement Development

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Reliability and Validity Analysis

3.5. Model Testing

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Contributions

4.2. Key Findings

4.3. Practical Implications

4.4. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1. Perceived Usefulness (PU) | 1. I have better sports performance when using online sports videos |

| 2. I have high exercise efficiency when using online sports videos | |

| 3. I find online sports videos useful | |

| 2. Behavioral Attitude (BA) | 1. I think using online sports videos is a good option |

| 2. I like to exercise using online sports videos | |

| 3. I think it’s feasible to use online sports videos for exercise | |

| 3. Subjective Norms (SNs) | 1. People who are important to me support me in exercising using online sports videos |

| 2. People who influence me think I should exercise using online sports videos | |

| 3. People whose opinions I value think I should use online sports videos for exercise | |

| 4. Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC) | 1. I will have the necessary resources, time and opportunity to use online sports videos |

| 2. Whether or not I exercise using online sports videos is entirely up to me | |

| 3. Exercising with online sports videos is completely within my control | |

| 5. Expected Confirmation (EC) | 1. My experience with online sports videos has been more than I expected |

| 2. The level of service provided by the online sports video was better than I expected | |

| 3. Online sports videos can be catered for beyond my requirements | |

| 6. Satisfaction (SAT) | 1. I’m happy with the performance of the online sports videos |

| 2. I’m happy with my experience of exercising using online sports videos | |

| 3. My decision to use online sports videos for exercise was wise | |

| 7. Continuance Intention (CI) | 1. I will continue to use online sports videos for exercise in the future |

| 2. I highly recommend it to others | |

| 8. Coach Social Existence (COA) | When I interact with my coach via video comments/likes etc…… |

| 1. Feeling like we’re together | |

| 2. I felt that the coach was interacting with me | |

| 3. I feel like the coach knows I’m there | |

| 4. The presence of a coach was obvious to me | |

| 5. I felt comfortable talking to the coach | |

| 9. Companion Social Existence (COM) | When I interact with other viewers via comments/pop-ups etc…… |

| 1. Feeling like we’re together | |

| 2. I feel like the rest of the audience is interacting with me | |

| 3. I think the rest of the audience is aware of my existence | |

| 4. The presence of other viewers is obvious to me | |

| 5. I feel comfortable interacting with them |

References

- Caspersen, C.J.; Powell, K.E.; Christenson, G.M. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: Definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 1985, 100, 126. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brehm, B.A.; Iannotta, J.G. Women and Physical Activity: Active Lifestyles Enhance Health and Well-Being. J. Health Educ. 1998, 29, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.J.; Xu, M.; Feng, Y.J.; Mao, Z.X.; Yan, Z.Y.; Fan, T.F. The value-added contribution of exercise commitment to college students’ exercise behavior: Application of extended model of theory of planned behavior. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 869997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, C. Gold’s Gym permanently closes 30 gyms across the US, due to coronavirus crisis. USA Today, 16 April 2020; 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z.; Wu, M. Understanding college students’ physical activities behavior in mobile age: An extension model of the theory of planned behavior (TPB) in WeChat fitness service. J. Phys. Act. Stud. 2016, 12, 34–56. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J.P. Smartphone applications for patients’ health and fitness. Am. J. Med. 2016, 129, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinnikova, A.; Lu, L.; Wei, J.; Fang, G.; Yan, J. The use of smartphone fitness applications: The role of self-efficacy and self-regulation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, J.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, J. Factors influencing fitness app users’ behavior in China. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Int. 2022, 38, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Huang, X.; Zhou, G. An empirical investigation into the impact of social media fitness videos on users’ exercise intentions. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, H.Y.; Seidel, L.; Pahud, M.; Sinclair, M.; Bianchi, A. FlowAR: How Different Augmented Reality Visualizations of Online Fitness Videos Support Flow for At-Home Yoga Exercises. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Hamburg, Germany, 23–29 April 2023; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Aranda, J.; Robles, E.M.G.; Urbistondo, P.A. Understanding antecedents of continuance and revisit intentions: The case of sport apps. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 72, 103288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadhan, A.; Hidayanto, A.N.; Salsabila, G.A.; Wulandari, I.; Jaury, J.A.; Anjani, N.N. The effect of usability on the intention to use the e-learning system in a sustainable way: A case study at Universitas Indonesia. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 1489–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, F.; Bazancir Apaydin, Z.; Sari, S. Assessment of reliability and quality of YouTube® exercise videos in people with rheumatoid arthritis. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, S.; Lee, J.; Jang, D. Climate change awareness and pro-environmental intentions in sports fans: Applying the extended theory of planned behavior model for sustainable spectating. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeng, M.Y.; Yeh, T.M.; Pai, F.Y. The continuous intention of older adults in virtual reality leisure activities: Combining sports commitment model and theory of planned behavior. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, C.; Hopkins, C.S. Applying theory of planned behavior to examine adolescent female athletes’ intentions of continued sport participation: 521. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2022, 54, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahanna, E.; Straub, D.W.; Chervany, N.L. Information technology adoption across time: A cross-sectional comparison of pre-adoption and post-adoption beliefs. MIS Q. 1999, 23, 183–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, Q.; Li, J. Examining continuance intention of online learning during COVID-19 pandemic: Incorporating the theory of planned behavior into the expectation–confirmation model. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1046407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacherjee, A. Understanding information systems continuance: An expectation-confirmation model. MIS Q. 2001, 25, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhang, J.; Shen, S. Exploring the pathway from seeking to sharing social support in e-learning: An investigation based on the norm of reciprocity and expectation confirmation theory. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 29461–29472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, S.; Mahmud, I.; Hoque, S.S.; Akter, R.; Rana, S.S. Predicting students’ intention to continue business courses on online platforms during the Covid-19: An extended expectation confirmation theory. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2022, 20, 100706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Wen, H.; Chen, M.; Yang, F. Sustainable Determinants Influencing Habit Formation among Mobile Short-Video Platform Users. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, S.; Choi, N. Understanding users’ continuance intention to use online library resources based on an extended expectation-confirmation model. Elect. Lib. 2016, 34, 554–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yu, Z. Understanding the continuance intention for artificial intelligence news anchor: Based on the expectation confirmation theory. Systems 2023, 11, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Song, H.D.; Kim, Y. Quality factors that influence the continuance intention to use MOOCs: An expectation-confirmation perspective. Eur. J.Psychol. Open. 2023, 82, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Bao, Y.; Yang, B.; Chen, S.; Zuo, Y.; Siponen, M. Investigating Students’ Satisfaction with Online Collaborative Learning During the COVID-19 Period: An Expectation-Confirmation Model. Group Decis. Negot. 2023, 32, 749–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persada, S.F.; Miraja, B.A.; Nadlifatin, R.; Belgiawan, P.F.; Perwira Redi AA, N.; Lin, S.C. Determinants of students’ intention to continue using online private tutoring: An expectation-confirmation model (ECM) approach. Technol. Knowl. Lear. 2021, 27, 1081–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawafak, R.M.; Al-Rahmi, W.M.; Almogren, A.S.; Al Adwan, M.N.; Safori, A.; Attar, R.W.; Habes, M. Analysis of E-learning system use using combined TAM and ECT factors. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, R.W.; Baker-Eveleth, L. Students’ expectation, confirmation, and continuance intention to use electronic textbooks. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 984–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopalle, P.K.; Lehmann, D.R. Strategic management of expectations: The role of disconfirmation sensitivity and perfectionism. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eveleth, D.M.; Baker-Eveleth, L.J.; Stone, R.W. Potential applicants’ expectation-confirmation and intentions. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 44, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.M. Examining students’ continued use of desktop services: Perspectives from expectation-confirmation and social influence. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 96, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.C.; Tang, Y.; Jiang, S. Understanding continuance intention of artificial intelligence (AI)-enabled mobile banking applications: An extension of AI characteristics to an expectation confirmation model. Hum. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Li, C.; Bai, S. Evaluating the couriers’ experiences of logistics platform: The extension of expectation confirmation model and technology acceptance model. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 998482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, C.; Wang, N.; Fang, J.; Huang, M. An Integrated Model of Continued M-Commerce Applications Usage. J. Comput. Inform. Syst. 2022, 63, 632–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mamun, R.; Senn, W.D.; Peak, D.A.; Prybutok, V.R.; Torres, R.A. Emotional satisfaction and IS continuance behavior: Reshaping the expectation-confirmation model. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Int. 2020, 36, 1437–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action Control: From Cognition to Behavior; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior, organizational behavior and human decision processes. Cited Hansen. 1991, 50, 93–114. [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, L. The theory of planned behaviour and the impact of past behaviour. Int. Bus. Econ. Res. J. 2011, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Wei, S.; Wang, Y.; Jiao, P. People’s Intentions to Use Shared Autonomous Vehicles: An Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.Z.; Xiao, Y.M.; Ma, Y.Y.; Li, C. Discussion of Students’ E-book Reading Intention With the Integration of Theory of Planned Behavior and Technology Acceptance Model. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 752188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Wang, P.; Jiang, Y.; Li, Q.; Li, Y. Innovative online learning strategies for the successful construction of student self-awareness during the COVID-19 pandemic: Merging TAM with TPB. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, N.; Lal, B.; Slade, E. Adoption of Two Indian E-Government Systems: Validation of Extended Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). In Proceedings of the Twenty-Second Americas Conference on Information Systems, Reno, NV, USA, 20–22 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rana, N.; Dwivedi, Y.; Slade, E.; Lal, B. Cyber-Slacking: Exploring Students’ Usage of Internet-Enabled Devices for Non-Class Related Activities. In Proceedings of the 2016 Americas Conference on Information Systems, San Diego, CA, USA, 11–14 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cheon, J.; Lee, S.; Crooks, S.M.; Song, J. An investigation of mobile learning readiness in higher education based on the theory of planned behavior. Comput. Educ. 2012, 59, 1054–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lung-Guang, N. Decision-making determinants of students participating in MOOCs: Merging the theory of planned behavior and self-regulated learning model. Comput. Educ. 2019, 134, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, S.; Heo, S.; Han, S.; Shin, Y.; Roh, Y. Acceptance model of artificial intelligence (AI)-based technologies in construction firms: Applying the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) in combination with the Technology–Organisation–Environment (TOE) framework. Buildings 2022, 12, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 982–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortunati, L.; Manganelli, A.M. The social representation of telecommunications. Pers Ubiquit Comput. 2008, 12, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawardena, C.N. Social presence theory and implications for interaction and collaborative learning in computer conferences. Int. J. Educ. Telecommuni 1995, 1, 147–166. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, O.V.; Taasoobshirazi, G. Social presence and teacher involvement: The link with expectancy, task value, and engagement. Internet High. Educ. 2022, 55, 100869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.C.; Maeda, Y.; Lv, J.; Caskurlu, S. Social presence in relation to students’ satisfaction and learning in the online environment: A meta-analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 71, 402–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos Reyes, D.; Koehler, A.; Richardson, J.C. The i-SUN Process to Use Social Learning Analytics: A conceptual Framework to Research Online Learning Interaction Supported by Social Presence. Front. Commun. 2023, 8, 1212324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, R.; Irby, T.L.; Wynn, J.T.; McClure, M.M. Investigating Students’ Satisfaction with eLearning Courses: The Effect of Learning Environment and Social Presence. J. Agric. Educ. 2012, 53, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostetter, C.; Busch, M. Measuring up online: The relationship between social presence and student learning satisfaction. J. Scholarsh. Teach. Learn. 2006, 6, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, M.; Liew, B.T.; Kim, J.; Park, Y. Learning presence as a predictor of achievement and satisfaction in online learning environments. Int. J. E-Learn. 2014, 13, 193–208. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, J.; Ma, L. Students’ online interaction, self-regulation, and learning engagement in higher education: The importance of social presence to online learning. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 815220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Q.; Zeng, Q.; Zhang, L. What social factors influence learners’ continuous intention in online learning? A social presence perspective. Inform. Technol. Peopl. 2023, 36, 1076–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyarzun, B.; Stefaniak, J.; Bol, L.; Morrison, G.R. Effects of learner-to-learner interactions on social presence, achievement and satisfaction. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2018, 30, 154–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orcutt, J.M.; Dringus, L.P. Beyond being there: Practices that establish presence, engage students and influence intellectual curiosity in a structured online learning environment. Online Learn. 2017, 21, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratan, R.; Ucha, C.; Lei, Y.; Lim, C.; Triwibowo, W.; Yelon, S.; Sheahan, A.; Lamb, B.; Deni, B.; Chen, V.H.H. How do social presence and active learning in synchronous and asynchronous online classes relate to students’ perceived course gains? Comput. Educ. 2022, 191, 104621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.M. How gamification and social interaction stimulate MOOCs continuance intention via cognitive presence, teaching presence and social presence? Libr. Hi Tech 2023, 41, 1781–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.C. Explaining and predicting users’ continuance intention toward e-learning: An extension of the expectation–confirmation model. Comput. Educ. 2010, 54, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Todd, P. Assessing IT usage: The role of prior experience. MIS Q. 1995, 19, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Todd, P.A. Understanding information technology usage: A test of competing models. Informa. Syst. Res. 1995, 6, 144–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, K.F.; Huyen, D.T.K.; Wang, X.; Qi, G. Factors influencing the adoption of shared autonomous vehicles. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, M.; Choi, H.; Park, S. Developing a social presence scale for measuring students’ involvement during e-learning process. Educ. Technol. Int. 2008, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Tang, D.; Tao, T.; Guo, N.; Li, S.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, X. The impact of tourism product harm crisis attribute on travel intention. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Education, Management, Information and Management Society (EMIM 2018), Shenyang, China, 21–23 September 2018; Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 461–466. [Google Scholar]

- Purnomo, Y.W. A Scale for Measuring Teachers’ Mathematics-Related Beliefs: A Validity and Reliability Study. Int. J. Instr. 2017, 10, 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Wu, G.; Zhou, X.; Lv, Y. An Empirical Study of the Factors Influencing User Behavior of Fitness Software in College Students Based on UTAUT. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Item | Factor Loading | Cronbach’ Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PU | PU1 | 0.721 | 0.759 | 0.754 | 0.505 |

| PU2 | 0.671 | ||||

| PU3 | 0.739 | ||||

| EC | EC1 | 0.663 | 0.711 | 0.717 | 0.458 |

| EC2 | 0.664 | ||||

| EC3 | 0.703 | ||||

| BA | BA1 | 0.681 | 0.714 | 0.693 | 0.430 |

| BA2 | 0.710 | ||||

| BA3 | 0.570 | ||||

| SAT | SAT1 | 0.759 | 0.732 | 0.720 | 0.464 |

| SAT2 | 0.669 | ||||

| SAT3 | 0.608 | ||||

| SNs | SNs1 | 0.802 | 0.772 | 0.755 | 0.536 |

| SNs2 | 0.718 | ||||

| SNs3 | 0.670 | ||||

| PBC | PBC1 | 0.685 | 0.704 | 0.705 | 0.444 |

| PBC2 | 0.612 | ||||

| PBC3 | 0.699 | ||||

| CI | CI1 | 0.746 | 0.716 | 0.642 | 0.474 |

| CI2 | 0.626 | ||||

| COA | COA1 | 0.717 | 0.814 | 0.808 | 0.512 |

| COA2 | 0.722 | ||||

| COA3 | 0.737 | ||||

| COA4 | 0.687 | ||||

| COM | COM1 | 0.816 | 0.841 | 0.841 | 0.571 |

| COM2 | 0.742 | ||||

| COM3 | 0.693 | ||||

| COM4 | 0.767 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PU | 0.711 | ||||||||

| 2. EC | 0.445 ** | 0.673 | |||||||

| 3. BA | 0.416 ** | 0.359 ** | 0.656 | ||||||

| 4. SAT | 0.397 ** | 0.365 ** | 0.322 ** | 0.681 | |||||

| 5. SNs | 0.420 ** | 0.332 ** | 0.346 ** | 0.369 ** | 0.732 | ||||

| 6. PBC | 0.411 ** | 0.396 ** | 0.328 ** | 0.307 ** | 0.396 ** | 0.666 | |||

| 7. CI | 0.488 ** | 0.469 ** | 0.421 ** | 0.396 ** | 0.428 ** | 0.506 ** | 0.689 | ||

| 8. COA | 0.232 ** | 0.212 ** | 0.314 ** | 0.258 ** | 0.262 ** | 0.198 ** | 0.248 ** | 0.716 | |

| 9. COM | 0.187 ** | 0.213 ** | 0.262 ** | 0.194 ** | 0.226 ** | 0.158 ** | 0.218 ** | 0.529 ** | 0.756 |

| Hypothesis (n = 305) | Unstd. | S.E. | C.R. | p | Std. | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 EC → PU | 0.672 | 0.077 | 8.752 | <0.001 *** | 0.814 | Supported |

| H2 PU → SAT | 0.515 | 0.152 | 3.395 | <0.001 *** | 0.454 | Supported |

| H3 EC → SAT | 0.422 | 0.132 | 3.209 | 0.001 ** | 0.451 | Supported |

| H4 SAT → CI | 387 | 0.129 | 3.009 | 0.003 ** | 0.422 | Supported |

| H5 BA → CI | 0.505 | 0.143 | 3.531 | <0.001 *** | 0.476 | Supported |

| H6 PU → BA | 0.904 | 0.089 | 10.145 | <0.001 *** | 0.923 | Supported |

| H7 SN → CI | 0.169 | 0.073 | 2.314 | 0.021 * | 0.223 | Supported |

| H8 PBC → CI | 0.250 | 0.078 | 3.193 | 0.001 ** | 0.281 | Supported |

| H9 COA → SAT | 0.388 | 0.129 | 3.007 | 0.003 ** | 0.490 | Supported |

| H10 COM → SAT | −0.299 | 0.110 | −2.708 | 0.007 ** | −0.436 | Not Supported |

| H11 COA → CI | −0.148 | 0.162 | −0.915 | 0.360 | −0.204 | Not Supported |

| H12 COM → CI | 0.093 | 0.119 | 0.782 | 0.434 | 0.148 | Not Supported |

| Hypothesis | Path | Male Results | Female Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | EC → PU | Supported | Supported |

| H2 | PU → SAT | Not Supported | Supported |

| H3 | EC → SAT | Supported | Supported |

| H4 | SAT → CI | Not Supported | Supported |

| H5 | BA → CI | Supported | Not Supported |

| H6 | PU → BA | Supported | Supported |

| H7 | SN → CI | Not Supported | Not Supported |

| H8 | PBC → CI | Not Supported | Supported |

| H9 | COA → SAT | Supported | Supported |

| H10 | COM → SAT | Supported | Supported |

| H11 | COA → CI | Not Supported | Supported |

| H12 | COM → CI | Not Supported | Not Supported |

| Hypothesis | Path | Have Experience | Have No Experience |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | EC → PU | Supported | Supported |

| H2 | PU → SAT | Supported | Supported |

| H3 | EC → SAT | Supported | Supported |

| H4 | SAT → CI | Supported | Supported |

| H5 | BA → CI | Supported | Supported |

| H6 | PU → BA | Supported | Supported |

| H7 | SN → CI | Supported | Not Supported |

| H8 | PBC → CI | Supported | Not Supported |

| H9 | COA → SAT | Supported | Supported |

| H10 | COM → SAT | Supported | Supported |

| H11 | COA → CI | Not Supported | Supported |

| H12 | COM → CI | Not Supported | Not Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pan, L.; Pan, X.; Mo, X.; Xia, T. Factors Influencing Willingness to Continue Using Online Sports Videos: Expansion Based on ECT and TPB Theoretical Models. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 510. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060510

Pan L, Pan X, Mo X, Xia T. Factors Influencing Willingness to Continue Using Online Sports Videos: Expansion Based on ECT and TPB Theoretical Models. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(6):510. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060510

Chicago/Turabian StylePan, Li, Xinyi Pan, Xiaohong Mo, and Tiansheng Xia. 2024. "Factors Influencing Willingness to Continue Using Online Sports Videos: Expansion Based on ECT and TPB Theoretical Models" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 6: 510. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060510

APA StylePan, L., Pan, X., Mo, X., & Xia, T. (2024). Factors Influencing Willingness to Continue Using Online Sports Videos: Expansion Based on ECT and TPB Theoretical Models. Behavioral Sciences, 14(6), 510. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060510