Strength Use and Well-Being at Work among Teachers: The Mediating Role of Basic Need Satisfaction

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. SU and Well-Being at Work

1.2. The Mediating Role of Basic Need Satisfaction

1.3. This Study

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Strength Use

2.2.2. Basic Need Satisfaction

2.2.3. Hedonic and Eudaimonic Well-Being at Work

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Ethics Statement

3. Results

3.1. Correlations among SU, Well-Being at Work, and Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction

3.2. Measurement Model

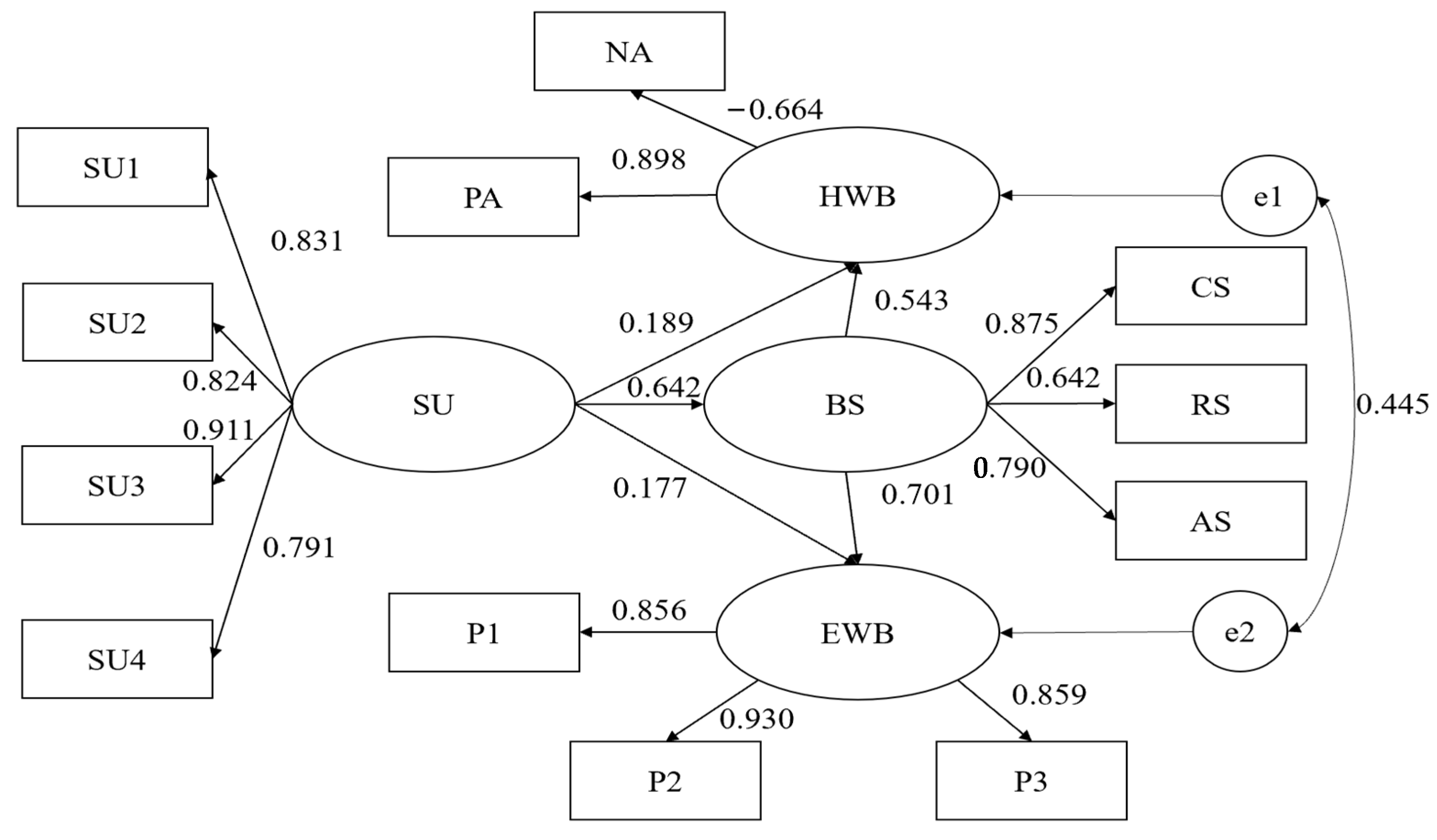

3.3. Structural Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdullah, A.; Ling, Y.L.; Peng, C.S. An exploratory analysis of happiness at workplace from Malaysian teachers perspective using performance-welfare model. Int. J. Asian Soc. Sci. 2016, 6, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorli, M.; Angelo, C.; Corvino, C. Innovation, participation and tutoring as key-leverages to sustain well-being at school. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindji, R.; Linley, P.A. Strengths use, self-concordance and well-being: Implications for strengths coaching and coaching psychologists. Int. Coach. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 2, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker; Hetland, J.; Olsen, O.K.; Espevik, R. Daily strengths use and employee well-being: The moderating role of personality. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2019, 92, 144–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JIN, W.; Zheng, X.; Gao, L. Basic psychological needs satisfaction mediates the link between strengths use and teachers’ work engagement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satici, S.A.; Uysal, R.; Akin, A. Investigating the relationship between flourishing and self-compassion: A structural equation modeling approach. Psychol. Belg. 2013, 53, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tov, W. Well-Being Concepts and Components. In Handbook of Subjective Well-Being; Noba Scholar: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Momtaz, Y.A.; Hamid, T.A.; Haron, S.A.; Bagat, M.F. Flourishing in later life. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2016, 63, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Yin, H.; Lv, L. Job characteristics and teacher well-being: The mediation of teacher self-monitoring and teacher self-efficacy. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 39, 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; King, R.B.; Fu, L.K.; Leung, S.O. Understanding Students’ Subjective and Eudaimonic Well-Being: Combining both Machine Learning and Classical Statistics. In Applied Research in Quality of Life; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nina, M.; Pratiwi, H.D.; Wahyuni, A.S.; Wahyuniar, L. Work family balance and optimism as a predictor of women worker’ subjective well-being. In Proceedings of the 2019 Ahmad Dahlan International Conference Series on Education & Learning, Social Science & Humanities (ADICS-ELSSH 2019), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 26–27 August 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundi, Y.M.; Aboramadan, M.; Elhamalawi, E.M.I.; Shahid, S. Employee psychological well-being and job performance: Exploring mediating and moderating mechanisms. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2020, 29, 736–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harzer, C.; Ruch, W. The application of signature character strengths and positive experiences at work. J. Happiness Stud. 2012, 14, 965–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, M. Character Strengths, Strengths Use, Future Self-Continuity and Subjective Well-Being Among Chinese University Students. Front Psychol 2018, 9, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Halbesleben, J.; Neveu, J.-P.; Westman, M. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyubomirsky, S.; Layous, K. How do simple positive activities increase well-being? Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 22, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M.S.; Jin, J. Exploring the basic psychological needs necessary for the internalized motivation of university students with smartphone overdependence: Applying a self-determination theory. J. Korean Acad. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 28, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The \“What\” and \“Why\” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Overview of self-determination theory: An organismic-dialectical perspective. Handb. Self-Determ. Res. 2002, 2, 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas, R.; García, T. Basic psychological needs, motivation and engagement in adolescent students. Rev. De Psicol. Del Deporte 2018, 27, 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Molinari, L.; Mameli, C. Basic psychological needs and school engagement: A focus on justice and agency. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2017, 21, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, A.E.; North, A.C.; Davidson, J.W. Using self-determination theory to examine musical participation and well-being. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, A.T.; Katigbak, M.S.; Locke, K.D. Need Satisfaction and Well-Being. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2012, 44, 507–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Cai, H.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Li, M.; Han, R.; Chen, S.X. Why does nature enhance psychological well-being?A Self-Determination account. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 83, 101872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.; Huta, V.; Deci, E. Living well: A self-determination theory perspective on eudaimonia. J. Happiness Stud. 2008, 9, 139–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, A.S.; Moran, C.M.; Gregory, J.B. How can humanistic coaching affect employee well-being and performance? An application of self-determination theory. Coach. Int. J. Theory Res. Pract. 2014, 7, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker; van Woerkom, M. Strengths use in organizations: A positive approach of occupational health. Can. Psychol. Psychol. Can. 2018, 59, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.T.; Ho, V.T. A self-determination perspective of strengths use at work: Examining its determinant and performance implications. J. Posit. Psychol. 2016, 11, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Woerkom, M.; Mostert, K.; Els, C.; Bakker, A.B.; de Beer, L.; Rothmann Jr, S. Strengths use and deficit correction in organizations: Development and validation of a questionnaire. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2016, 25, 960–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerasoli, C.P.; Nicklin, J.M.; Nassrelgrgawi, A.S. Performance, incentives, and needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness: A meta-analysis. Motiv. Emot. 2016, 40, 781–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, S.M.; Van Dyne, L.; Kamdar, D. The contextualized self: How team-member exchange leads to coworker identification and helping OCB. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 583–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.; Li, J.; Mu, W. Psychometric characteristics of strengths knowledge scale and strengths use scale among adolescents. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 2017, 36, 756–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci; Ryan, R.M.; Gagné, M. Need satisfaction, motivation, and well-being in the work organizations of a former eastern bloc country: A cross-cultural study of self-determination. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 27, 930–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Wirtz, D.; Tov, W. New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc. Indic. Res. 2009, 97, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David; Cramer, R.J.; Grubka, J.M. Spirituality, life stress, and affective well-being. J. Psychol. Theol. 2007, 35, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Zhao, J.; You, X. Social support mediates the impact of emotional intelligence on mental distress and life satisfaction in Chinese young adults. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2013, 53, 513–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackinnon, D.P.; Lockwood, C.M.; Williams, J. Confidence Limits for the Indirect Effect: Distribution of the Product and Resampling Methods. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2004, 39, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumann, D.; Eiroa-Orosa, F.J. Mental well-being in later life: The role of strengths use, meaning in life, and self-perceptions of ageing. Int. J. Appl. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 1, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, C.; Maltby, J.; Linley, P. Strengths use as a predictor of well-being and health-related quality of life. J. Happiness Stud. 2011, 12, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A.M.; Linley, P.A.; Maltby, J.; Kashdan, T.B.; Hurling, R. Using personal and psychological strengths leads to increases in well-being over time: A longitudinal study and the development of the strengths use questionnaire. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2011, 50, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littman-Ovadia, H.; Lazar-Butbul, V.; Benjamin, B.A. Strengths-based career counseling: Overview and initial evaluation. J. Career Assess. 2013, 22, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Woerkom, M.; Oerlemans, W.; Bakker, A.B. Strengths use and work engagement: A weekly diary study. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2015, 25, 384–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.; Bai, B.; Kong, F. Strength use and nurses’ depressive symptoms: The mediating role of basic psychological needs satisfaction. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 1660–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miglianico, M.; Dubreuil, P.; Miquelon, P.; Bakker, A.B.; Martin-Krumm, C. Strength use in the workplace: A literature review. J. Happiness Stud. 2019, 21, 737–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Strength use | 17.29 (3.53) | -- | |||

| 2. Basic psychological need satisfaction | 33.44 (4.85) | 0.558 *** | -- | ||

| 3. Hedonic well-being | 4.91 (7.63) | 0.491 *** | 0.520 *** | -- | |

| 4. Eudaimonic well-being | 44.06 (7.83) | 0.582 *** | 0.705 *** | 0.618 *** | -- |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wei, C.; Su, J.; Zhao, J.; Ding, K.; Kong, F. Strength Use and Well-Being at Work among Teachers: The Mediating Role of Basic Need Satisfaction. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14020095

Wei C, Su J, Zhao J, Ding K, Kong F. Strength Use and Well-Being at Work among Teachers: The Mediating Role of Basic Need Satisfaction. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(2):95. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14020095

Chicago/Turabian StyleWei, Cangpi, Jiahe Su, Jingjing Zhao, Ke Ding, and Feng Kong. 2024. "Strength Use and Well-Being at Work among Teachers: The Mediating Role of Basic Need Satisfaction" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 2: 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14020095

APA StyleWei, C., Su, J., Zhao, J., Ding, K., & Kong, F. (2024). Strength Use and Well-Being at Work among Teachers: The Mediating Role of Basic Need Satisfaction. Behavioral Sciences, 14(2), 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14020095