1. Introduction

Urban–rural inequality in educational outcomes is a classic and vital issue worldwide, and urban–rural education gaps are especially huge in developing countries, such as Russia [

1], Ghana [

2], and Vietnam [

3]. In contemporary China, despite the educational expansion that has occurred in the last two decades, effectively increasing the educational opportunities for rural children, the urban–rural gap has not narrowed, especially in terms of educational outcomes, and the concern of urban–rural educational inequality is still a crucial social problem [

4,

5,

6].

Family socioeconomic status (SES) is considered an essential factor in explaining educational inequality in the existing literature from both Eastern and Western countries. Scholars agree that there is a correlation between family SES and various educational outcome variables [

7,

8,

9,

10], and this family SES effect is stable across geographic and temporal borders [

11]. According to the literature, parental advantages can be transmitted to children through two paths. First, parental advantages can directly enhance children’s achievements by the provision of high-quality educational resources [

12] (p. 29), including both in- and out-of-school educational resources. In-school resources focus on the school environment, teaching facilities, and faculty strength within the school [

13,

14,

15], whereas out-of-school resources emphasize summer programs, extracurricular activities, private tutoring, and shadow education [

16,

17,

18,

19]. Second, family SES indirectly affects children’s achievements through specific cultural factors, including education-related attitudes, educational expectations, family cultural capital, parent–child interactions, and family tutoring [

13,

20,

21,

22], all of which are important mediating variables connecting family SES and children’s achievements.

All the aforementioned studies assumed that the influence of family SES on achievement does not vary among different groups of children when explaining educational inequality; however, this assumption is debatable. Transferring family SES advantages to children’s achievements requires specific resources, culture, and environments which are usually nested in social structure. Children in different social structural positions may face drastic distinctions in their educational environments and resources. Therefore, the influence of family SES on children’s achievements may differ in groups with different structural attributes. In Western literature, researchers have proposed that race is an essential structural factor that moderates the association between family SES and achievement. In explaining why Asian Americans academically outperform White people despite their socioeconomic disadvantages, scholars have stated that family SES has a more significant impact on their achievements, whereas Asian Americans rely on positive educational attitudes and high educational expectations to promote their achievements [

23,

24]. Household registration, which is unique in China, is another significant structural factor within the Chinese context. The household registration system is a fundamental system in China for population regulation based on place of residence. Household registration can be transferred from generation to generation, which means children’s household registrations will follow one of their parents’ household registrations, regardless of their actual living areas. Location and type are the two most crucial attributes of the household registration system. Location distinguishes the place people live according to Chinese administration planning, and type divides people into agricultural and non-agricultural household registration according to rural/urban types of residence. In this study, we focus on the different types of household registration. We regard people holding agricultural household registration as rural residents, and people holding non-agricultural household registration as urban residents. The household registration system, established by the urban–rural binary system, divides the population into urban and rural residents. People holding different household registrations may have significant differences not only in terms of geographic living area, but also in resources, environment, and culture. As a result, such a structural divide may lead to different processes of transforming family SES into achievement among urban and rural children. Such a conclusion is supported by empirical studies with similar results. For example, a Chinese study discovered the distinct impact of family SES on achievement by analyzing different pathways of children’s school learning. The study showed that family SES had a significantly more positive impact on achievement among urban children than among rural children. In contrast, rural children’s achievements are more closely related to their learning behaviors [

25]. The moderating role of household registration is an essential issue for urban–rural educational equalization because it shows different patterns of family SES and achievement associations between rural and urban areas, and this may lead to different strategies for improving children’s achievements, especially for resource allocation and policy orientation in rural areas. However, in the previous literature, few studies systematically analyzed the relationship between household registration, family SES, and achievement. Given this literature gap, this study aims to examine the moderating role of household registration in the relationship between family SES and achievement by asking the research question: Does family SES have a heterogeneous effect on achievement across urban and rural children?

In the context of Chinese household registration system, compared with children from rural areas, urban families are more likely to possess better family SES, which is due to unequal economic development between urban and rural areas in China, and such advantages of urban families can be transformed into better achievements for urban children in both direct and indirect ways, as mentioned before. In addition, since resources and culture are key factors in the processes of converting family SES into achievement [

21,

26,

27,

28] and there are limited educational resources and a negative culture around education for rural children, they are more likely to have lower efficiency in converting family SES into achievement than their urban counterparts. Based on the above analysis, Hypotheses 1 and 2 are proposed.

Hypothesis 1. Urban children generally have better achievements than rural children because of their higher family SES.

Hypothesis 2. Family SES has a heterogeneous effect on achievement among urban and rural children. Compared with urban children, family SES has a weaker positive effect on achievement among rural children.

In addition to the patterns of “Family SES-achievement” among different groups, the internal mechanisms and implications are studied as well. Studies from Western countries demonstrated that the heterogenous effect of family SES on achievement in terms of race is through culture. Researchers found that Asian American children tend to perform better academically than White children [

15]. Why can Asian Americans achieve academic success despite their relatively low family SES? Researchers suggest that, compared to White families, Asian American families are more serious about education and act upon a stronger belief that education facilitates upward mobility. Owing to the unique Asian education culture, Asian Americans are more likely to achieve positive educational outcomes, even if they have disadvantages in family SES [

24,

29]. Furthermore, cultural factors moderate the relationship between family SES and educational outcomes. Compared with White people, family SES has a minor influence on achievement and cultural factors among Asian Americans, who are more influenced by Asian culture. This conclusion suggests a heterogeneous impact of family SES on educational outcomes based on race, in which culture plays an essential role [

23].

Chinese scholars also noticed culture as a mediating mechanism between family background and achievement by focusing on cultural factors, including educational expectations, cultural capital, cultural environment, and cultural beliefs [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. An empirical study showed that the advantages of parental education can be transmitted to children through cultural reproduction. Educational expectations, cultural capital, and human capital are the three main mechanisms in this process [

21]. Another study suggested that the effect of cultural capital on achievement varies across social classes and schools. Compared to children from low-SES families and lower-quality schools, cultural capital has a more significant promoting effect on achievement among children from high-SES families and higher-quality schools; the author calls this “dual reproduction” [

22].

The above literature revealed the analytical framework of the racial moderating effect by emphasizing the mediating role of the cultural differences of race within the Western context. Chinese studies also demonstrated the cultural influence on educational inequality. However, the existing studies provide unclear information on the combination of the cultural mediating effect and household registration moderating effect. This study aims to explore the internal mechanism of urban–rural heterogeneous effects of family SES on children’s achievements and will try to analyze the mediating role of culture.

Although different moderating structural variables may lead to different mechanisms, the analytical frameworks of race offer significant implications for comprehending urban–rural educational inequality in China. Traditional Confucianism culture influences both urban and rural Chinese families, but cultural disparities still exist between urban and rural areas in terms of education. Middle-class families in cities with higher family SES tend to share an elite culture around education to prevent downward mobility for the next generation. They usually aim for higher education and regard educational success as one of the most valuable events in their children’s lives [

35]. In contrast, rural educational culture is more practical. Rural families with relatively high family SES may possess passive values on education due to the low rate of return from education in rural areas [

36], and their children may form negative learning beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors, and enter schools with disadvantaged learning environments and atmospheres. Therefore, the advantages of family SES can be converted differently into positive education-related cultural factors for urban and rural families, leading to urban–rural achievement gaps as a consequence. In this sense, education-related cultural factors mediate the heterogeneous effects of family SES on achievement. The education-related cultural factors in this study refer to the most essential learning attributes influenced by culture, as mentioned before, i.e., learning environments and beliefs. Based on the above analysis, Hypotheses 3 and 4 are proposed.

Hypothesis 3. Family SES has a heterogeneous effect on education-related cultural factors among urban and rural children. Compared with urban children, family SES has a weaker positive effect on education-related cultural factors among rural children.

Hypothesis 4. Education-related cultural factors mediate the urban–rural heterogeneous effect of family SES on achievement.

By exploring the different urban and rural family SES achievement patterns, and the internal mechanism of culture, this study aspires to discuss a more theoretical issue regarding education in Chinese society, that is, will urban–rural educational inequality be reduced, maintained, or expanded?

There are two competing theories on educational inequality in Western literature: cultural mobility and cultural reproduction theory. According to industrialization theory, with widespread industrialization and a more specialized labor division, parental resources and advantages from family SES cannot be directly transmitted to children. Instead, children gain these advantages through competition in education and through careers. Due to the continuous expansion of education and the enhancement of educational opportunities, the impact of ascribed and structural factors brought about by family SES on educational outcomes will gradually decrease, whereas the influence of achieved factors, such as effort, attitude, and belief, will increase. In this sense, education will reduce class inequality [

37]. Empirical studies also showed that the achievement gap between high- and low-social-class students grows faster during vacation periods than during school hours [

38,

39], which indicates that children of lower SES families can accomplish upward mobility through the education system by actively acquiring the advantages of prestigious status cultures from high-status socioeconomic families. This is called the cultural mobility model [

40]. Another opinion suggests that education may maintain or even expand social class inequality; the most representative theory is the cultural reproduction theory. This theory proposes that social and educational inequality is not at the individual level, but is embedded within social structure. Cultural capital can be transmitted across generations through an educational system within a structure, resulting in social reproduction. Cultural capital refers to the cultural factors embedded in structures and institutions and includes three forms: disposition of the mind and body, cultural goods, and an institutionalized state [

41] (p. 235). Families in higher social classes provide their children with prestigious cultural resources that can be transformed into positive educational outcomes and higher occupational status through the education system. Thus, children can maintain the social status of their previous generations and achieve cultural reproduction.

In the Chinese context, studies consistently show that the cultural reproduction model is more suitable for contemporary China in terms of social inequality of class [

21,

22], but few studies test the two competing theories in terms of urban–rural inequality. This study will contribute to discussing the role of the education system in contemporary China and how Western inequality theories apply in China in terms of urban–rural educational inequality. If Hypothesis 1 is supported, it means that the family SES advantages among urban children can be directly transferred into their achievement advantages. If Hypotheses 2–4 are supported, it means that the family SES advantages among urban children can be indirectly transferred into achievement advantages through education-related cultural variables, and such transfer is more effective for urban children. The moderating role of household registration and the mediating role of culture are tested. Therefore, urban–rural achievement gaps will expand due to existing gaps in family SES between urban and rural children, and contemporary China will experience a cultural reproduction mode rather than a cultural mobility mode.

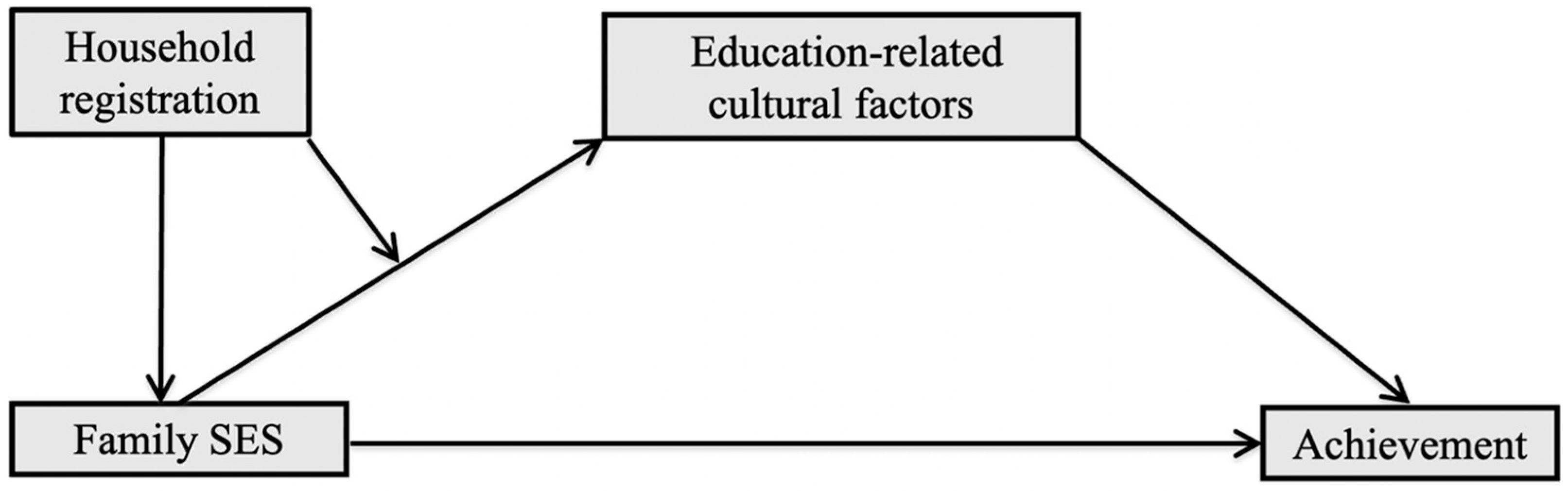

In summary, this study attempts to answer the following research questions: (1) Does household registration modify the relationship between family SES and achievement, and how? (2) Does culture play a mediating role in such a heterogeneous effect in terms of household registration? (3) Which theoretical model, cultural reproduction or cultural mobility mode, is more applicable to contemporary China? Based on the literature, this study hypothesizes that rural children possess not only lower family SES but also weaker associations between family SES and achievement, and as a result rural children will have worse achievements than urban children. We also hypothesize that education-related cultural factors play a mediating role in such a relationship. That is to say, family SES has a weaker positive effect on education-related cultural factors among rural children than their urban counterparts, and this will lead to an urban–rural achievement gap. The relationships of different variables are shown in the theoretical framework (

Figure 1). To test the hypotheses, this study plans to use the China Education Panel Survey (CEPS) data of 18,672 junior high school students, including 10,126 rural students and 8546 urban students. Random-effects models and OLS regression with clustered standard errors will be selected in the data analysis due to the research questions and data structure. Furthermore, this study offers policy implications for policymakers concerned with rural educational development and urban–rural equalization in educational outcomes.

This study contributes to the literature in three ways. First, although the existing literature has extensively researched the effect of family SES on children’s educational outcomes, few researchers have noticed that family SES effect varies between urban and rural children. This study enriches the literature on the effect of family SES by examining how family SES influences children’s achievements differently with different household registrations, which helps disentangle a more precise relationship between family SES and educational outcomes. Second, there are a large number of studies discussing the mediating role of cultural factors in educational inequality, but less attention has been paid to the linkage between the moderating role of household registration and the mediating role of culture. This study enriches the literature on the mediating role of cultural variables in urban–rural educational inequality. Third, this study further verifies the applicability of cultural reproduction and mobility models within the Chinese context, enriching the literature on the validation of classical educational inequality theories and providing data support for understanding the patterns and mechanisms of education inequality in contemporary China.

4. Discussion

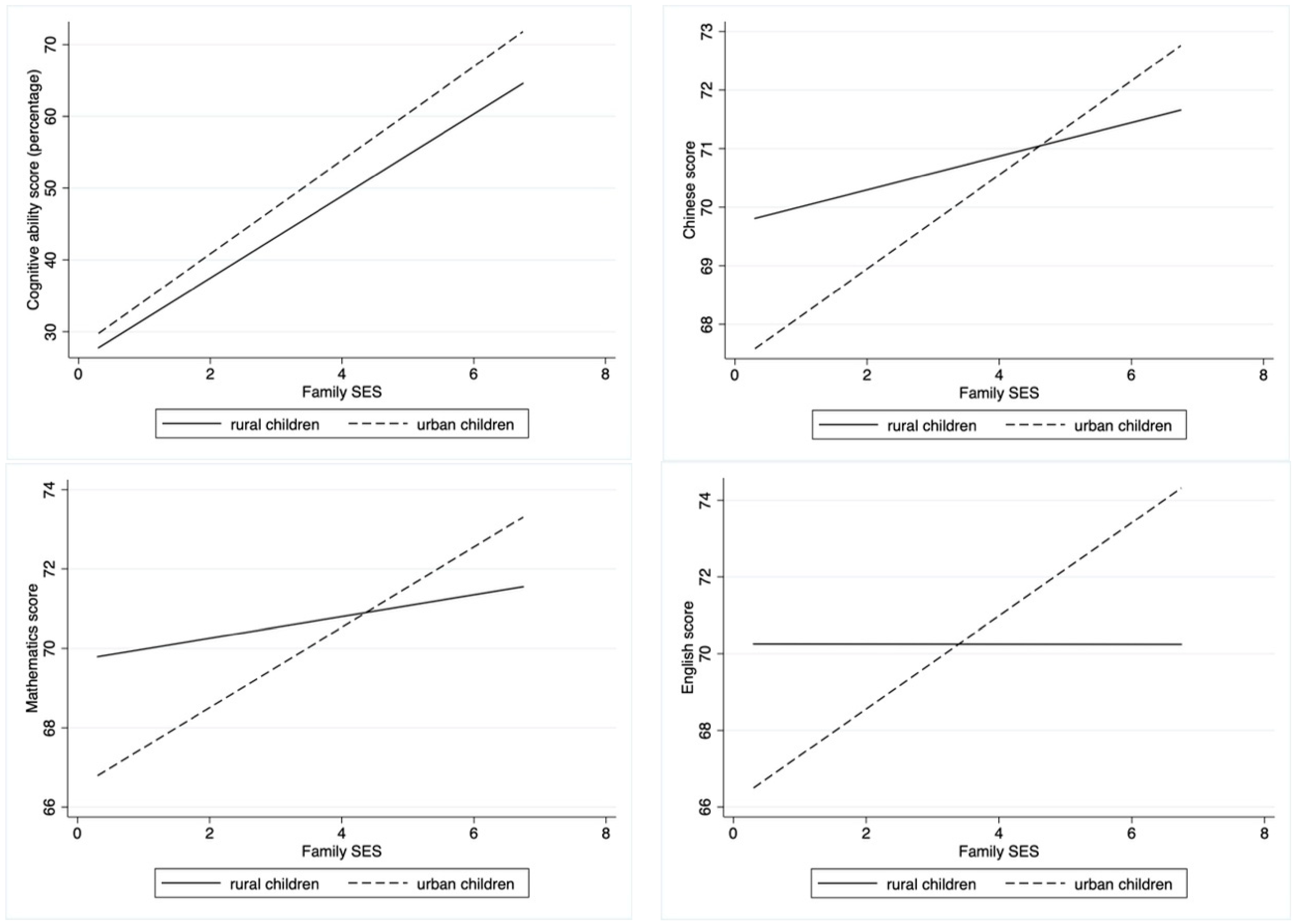

This study indicated different patterns between family SES and achievement in urban and rural areas, and the relationship between family SES and achievement was stronger in urban areas than in rural areas. The findings respond to the first research question, and the findings are consistent with the patterns of the previous study by Wu et al. [

22]. In addition, this study also revealed that the urban–rural heterogeneous effect of family SES on achievement is the result of the urban–rural heterogeneous effect of family SES on learning environments and beliefs, which determines that education-related cultural factors are important to academic success. The results answer the second research question. The mediating effect of culture is similar to that found in Western studies [

15,

23]. Given the giant economic development gap between urban and rural areas, urban children not only have better family SES but can also more effectively transform SES advantages into achievement advantages through learning environments and beliefs, which may encourage them to obtain higher education levels and occupational status in the future. Owing to the above findings, Chinese society remains in a mode of cultural reproduction, and our conclusion confirms previous studies regarding class inequality [

21,

22], which answers the third research question. “Impoverished families can hardly nurture rich sons” is a popular phrase in China, meaning that children from low SES families can hardly achieve success. Such a phrase reflects the public opinion that deems family SES a strong predictor of academic success. We concede that the family SES gap plays a vital role in urban–rural educational inequality in China and other countries [

1,

46,

47], and with economic development and increasing income in both rural and urban areas, the urban–rural educational gap may further expand in the future due to the pattern of family SES heterogeneous effect shown in this study. The education system continues to play a role in maintaining or expanding the inequality of urban and rural education under the existing household registration and education system.

However, the weaker relationship between achievement and family SES in rural areas suggests that the monetary influence of the family is less important for rural children’s achievements, and their achievements rely more on cultural factors, which is similar to the conclusion of a previous study [

25]. As a result, improving rural children’s learning environments and beliefs opens up possibilities of alleviating the disadvantages in cognitive and academic achievement due to lower family SES because these cultural factors are not rigidly associated with family SES. In this sense, learning environments and beliefs play a positive role in breaking intergenerational status replication and suggest the possibility that children from low-SES families may have positive educational outcomes and future career development.

The above discussions yield policy implications from a cultural perspective for promoting urban–rural equalization. First, they promote the culture revitalization program in rural areas, which is one of the five essential aspects of the rural revitalization strategy in China. The rural revitalization strategy was proposed at the 19th CPC National Congress in 2017 in China. The goal of the rural revitalization strategy is to promote the development of rural areas. It includes five dimensions, and culture revitalization is one of the five revitalizations. Central government needs to pay more attention to this cultural aspect by improving the overall educational attitudes and beliefs of children, educators, and families in rural counties. Cultural lag theory points out that in the process of social change, changes in material culture always occur before changes in non-material culture [

48]. This theory implies that, although the poverty alleviation program in China has dramatically improved the hardware infrastructure in rural areas, changes in the cultural environment of rural schools and families may be left behind. In contemporary China, many rural parents, and even teachers, still think that education is useless for children’s future development. Such beliefs lead to low expectations, unclear study motivation, and negative study behavior, and harm educational outcomes as a result. In this context, the government needs to put more effort into helping rural educators and families establish positive attitudes and beliefs toward education. Second, education informatization strategies, like massive open online courses (MOOCs) and mobile learning, should be encouraged in rural areas. Education informatization will not only share urban education resources to rural areas, but also promote urban–rural cultural integration. Although there is no level of superiority between urban and rural cultures, urban culture is more conducive to children’s educational outcomes than rural culture. Therefore, actively achieving education-related urban culture will benefit rural children in the process of cultural integration. With improvements in Internet hardware, online education facilitates rural children not only in enhancing educational resources, but in promoting positive urban culture regarding educational beliefs, attitudes, and environments. Through online education, rural children are more likely to be influenced by positive urban culture and further enhance their educational outcomes.

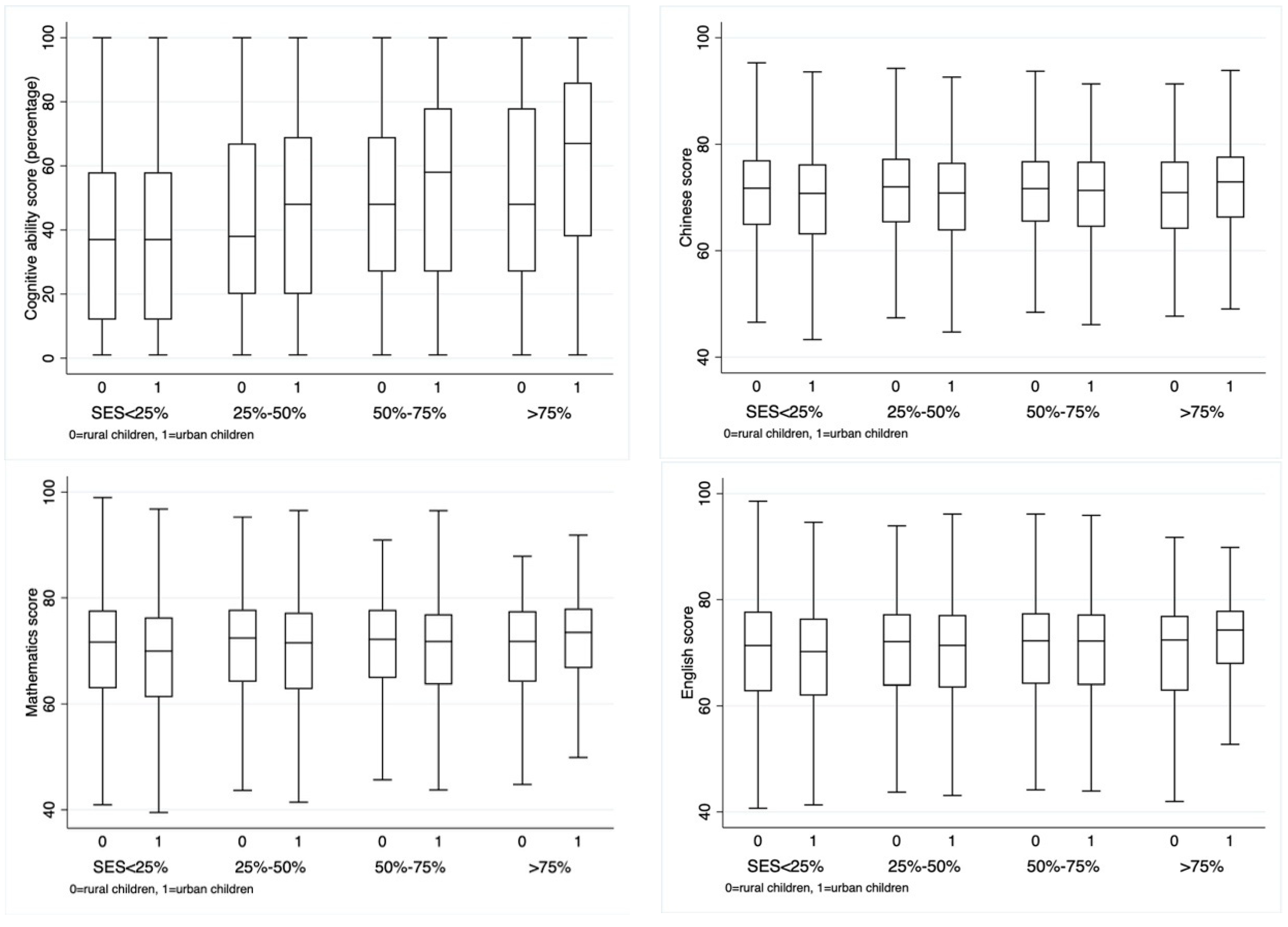

This study has certain limitations. First, the research findings are based on a linear relationship between family SES and achievement; however, a nonlinear relationship is possible. One possibility is that higher family SES promotes children’s achievements more than lower family SES. On average, urban children have higher family SES than rural children, which may result in a more significant family SES effect in urban areas. To further investigate this issue, the author divided the sample into two subsamples based on family SES (high- and low-SES subsamples). In the models of the two subsamples, the interaction term of household registration and family SES was significant for children’s achievements in the high-SES subsample, but insignificant in the low-SES subsample (due to space limitations, these two models are not presented in the article). The results suggest that the impact of family SES on achievement varies among different SES subsamples, and a nonlinear relationship is possible. However, even if there is a nonlinear relationship, the urban–rural heterogeneous effect of family SES on achievement still exists in the subsample with higher SES. Therefore, the results of the present study are still valid. Second, due to data limitations, the measurements of certain variables are not precise enough, which may affect the reliability and validity of the statistical results. It is noted that self-reported economic conditions as a proxy may not reflect family income objectively, and standardized exam scores in Chinese, Math, and English may still have problems in comparison across different schools because of different difficulties. However, subjective and objective economic status are highly correlated [

42], and the patterns of family SES effect on exam scores are consistent with family SES effect on the cognitive achievement score. Therefore, the two variables are valid in the statistical analysis.

Future research can be expanded into three aspects. First, further discussion can be conducted on how the heterogeneous effect and nonlinear relationship commonly influence children’s achievements to more accurately clarify the relationship between family SES, household registration, and achievement. Second, this study only examined the mediating effect of learning environments and beliefs; more cultural factors could be included in the framework of family SES heterogeneous models in future studies. Third, this study is based on the background of the unique Chinese binary household registration system, but the issue of urban–rural educational inequality is a worldwide issue. More comparisons across countries can be conducted in the future.