The Relationship between Childhood Abuse and Suicidal Ideation among Chinese College Students: The Mediating Role of Core Self-Evaluation and Negative Emotions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Common Method Deviation Test

3.2. Preliminary Analysis

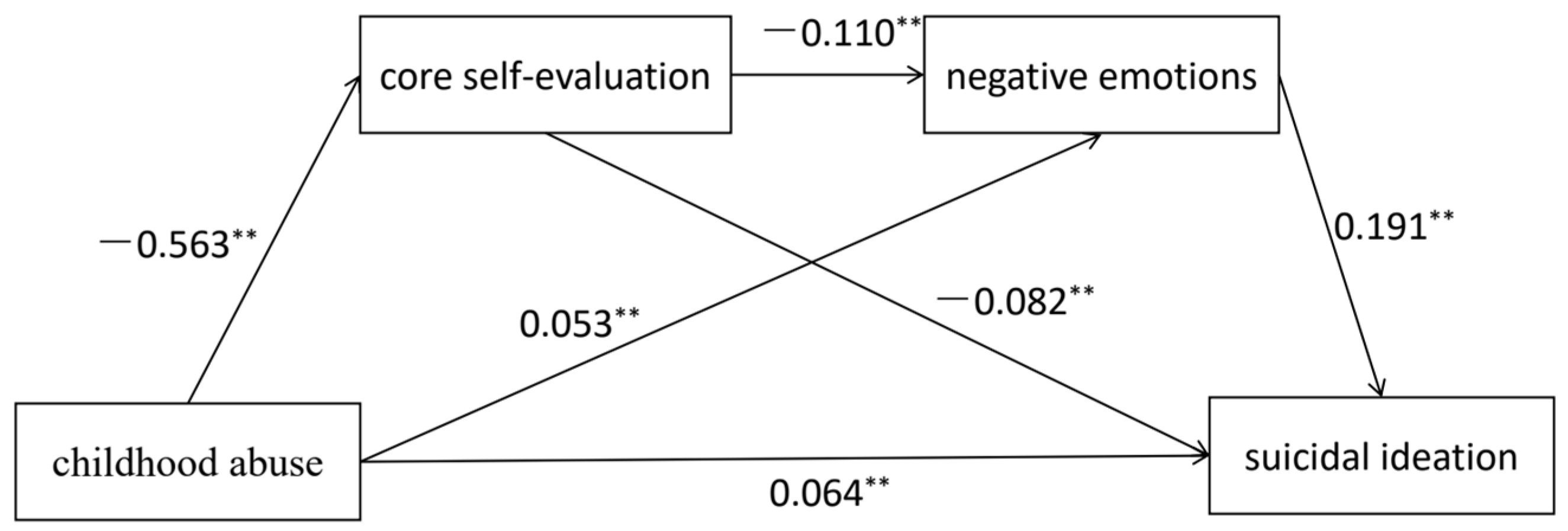

3.3. Testing for Mediating Effects

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Glenn, C.R.; Kleiman, E.M.; Kellerman, J.; Pollak, O.; Cha, C.B.; Esposito, E.C.; Porter, A.C.; Wyman, P.A.; Boatman, A.E. Annual Research Review: A Meta-Analytic Review of Worldwide Suicide Rates in Adolescents. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2020, 61, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallford, D.J.; Rusanov, D.; Winestone, B.; Kaplan, R.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M.; Melvin, G. Disclosure of Suicidal Ideation and Behaviours: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Prevalence. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2023, 101, 102272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janiri, D.; Doucet, G.E.; Pompili, M.; Sani, G.; Frangou, S. Risk and Protective Factors for Childhood Suicidality: A US Population-Based Study. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Kou, C.; Bai, W.; Song, Y.; Liu, X.; Yu, W.; Li, Y.; Hua, W.; Li, W. Prevalence and Correlates of Suicidal Ideation Among College Students: A Mental Health Survey in Jilin Province, China. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 246, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinchin, I.; Doran, C.M. The cost of youth suicide in Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlewska, K.; Orlewska, E. Burden of suicide in Poland in 2012: How could it be measured and how big is it? Eur. J. Health Econ. 2018, 19, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ireland, T.O.; Smith, C.A.; Thornberry, T.P. Developmental Issues in the Impact of Child Maltreatment on Later Delinquency and Drug Use. Criminology 2002, 40, 359–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.S.; Naimi, A.I.; Brooks, M.M.; Richardson, G.A.; Burke, J.G.; Bromberger, J.T. Life-Course Impact of Child Maltreatment on Midlife Health-Related Quality of Life in Women: Longitudinal Mediation Analysis for Potential Pathways. Ann. Epidemiol. 2020, 43, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.S.; Pierce, H. Early Exposure to Adverse Childhood Experiences and Youth Delinquent Behaviour in Fragile Families. Youth Soc. 2021, 53, 841–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, D.P.; Ahluvalia, T.; Pogge, D.; Handelsman, L. Validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in an Adolescent Psychiatric Population. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1997, 36, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagan, A.A. Child Maltreatment and Aggressive Behaviors in Early Adolescence: Evidence of Moderation by Parent/Child Relationship Quality. Child Maltreat. 2020, 25, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Peng, C.; Chang, H.; Yu, M.; Rong, F.; Yu, Y. Interaction Between Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) Polymorphisms and Childhood Maltreatment on Aggression Risk in Chinese Male Adolescents. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 309, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cernat, V.A. Coherence Optimization Model of Suicide. 11 May 2011. Available online: http://cogprints.org/1081/1/coherencesuicide.htm (accessed on 14 November 2023).

- Wang, Q.; Tu, R.; Hu, W.; Luo, X.; Zhao, F. Childhood Psychological Maltreatment and Depression Among Chinese Adolescents: Multiple Mediating Roles of Perceived Ostracism and Core Self-Evaluation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, Y.H.; Yuan, R.; Zhao, J.X. The Relationship Between Childhood Maltreatment and Loneliness in Adulthood: The Mediating Role of Rumination and Core Self-Evaluation. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 44, 191–198. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, T.A.; Locke, E.A.; Durham, C.C. The Dispositional Causes of Job Satisfaction: A Core Evaluations Approach. Res. Organ. Behav. 1997, 19, 151–188. [Google Scholar]

- Ono, K.; Takaesu, Y.; Nakai, Y.; Shimura, A.; Ono, Y.; Murakoshi, A.; Matsumoto, Y.; Tanabe, H.; Kusumi, I.; Inoue, T. Associations Among Depressive Symptoms, Childhood Abuse, Neuroticism, and Adult Stressful Life Events in the General Adult Population. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2017, 13, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greger, H.K.; Myhre, A.K.; Klöckner, C.A.; Jozefiak, T. Childhood Maltreatment, Psychopathology and Well-Being: The Mediator Role of Global Self-Esteem, Attachment Difficulties and Substance Use. Child Abuse Negl. 2017, 70, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, F.Y.; Wen, S.; Deng, G.; Tang, Y.L. Self-Concept Mediates the Relationship Between Childhood Maltreatment and Abstinence Motivation as well as Self-Efficacy Among Drug Addicts. Addict. Behav. 2017, 68, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roazzi, A.; Attili, G.; Di Pentima, L.D.; Toni, A. Locus of Control in Maltreated Children: The Impact of Attachment and Cumulative Trauma. Psicol. Refl. Crít. 2016, 29, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and Validation of Brief Measures of Positive and Negative Affect: The Panas Scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousson, A.N.; Fleming, C.B.; Herrenkohl, T.I. Childhood Maltreatment and Later Stressful Life Events as Predictors of Depression: A Test of the Stress Sensitization Hypothesis. Psychol. Violence 2020, 10, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cross, B.J.; Collard, J.J.; Levidi, M.D.C. Core Self-Evaluation, Rumination and Forgiveness as an Influence on Emotional Distress. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 42, 2087–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.W.; Zhou, H.; Xiao, W.L. Boredom Proneness and Core Self-Evaluation as Mediators Between Loneliness and Mobile Phone Addiction Among Chinese College Students. Front. Psychol. 2022, 59, 628–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.B. The Relationship Between Perfectionism, Core Self-Evaluation and Career Anxiety Among College Graduates. Chin. J. Behav. Brain Sci. 2015, 24, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys, K.L.; Lemoult, J.; Wear, J.G.; Piersiak, H.A.; Lee, A.; Gotlib, I.H. Child Maltreatment and Depression: A Meta-analysis of Studies Using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. 2020, 102, 104361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infurna, M.R.; Reichl, C.; Parzer, P.; Schimmenti, A.; Bifulco, A.; Kaess, M. Associations Between Depression and Specific Childhood Experiences of Abuse and Neglect: A Meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 190, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gijzen, M.W.M.; Rasing, S.P.A.; Creemers, D.H.M.; Smit, F.; Engels, R.C.M.E.; De Beurs, D. Suicide Ideation as a Symptom of Adolescent Depression: A Network Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 278, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, C. The Influence of Childhood Psychological Abuse on Psychological Vulnerability Among College Students—A Moderated Mediation Model. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 29, 1064–1068. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Pan, Y.; Liu, G.; Chen, W.; Lu, J.; Li, X. Perceived social support and self-esteem mediate the relationship between childhood maltreatment and psychosocial flourishing in Chinese undergraduate students. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 117, 105303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Ranieri, W.F. Scale for Suicide Ideation: Psychometric Properties of a Self-Report Version. J. Clin. Psychol. 1988, 44, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ara, S.; Ahad, R. Depression and Suicidal Ideation Among Older Adults of Kashmir. Int. J. Indian Psychol. 2016, 3, 136–145. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.Y.; Fei, L.P.; Zhang, Y.L.; Xu, D.; Tong, Y.S.; Yang, P.D. Reliability and Validity of the Chinese Version of Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (BSI-CV) Among University Students. Chin. J. Ment. Health 2011, 25, 862–866. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.C.; Gou, C.Y.; Liu, L.; Ge, X.; Guo, T.; Li, F. Suicidal Ideation and Online Counselling Attitudes Among College Students: The Mediating Effect of Stigma and Online Self-Disclosure. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2023, 31, 230–234. [Google Scholar]

- Du, J.Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y. Reliability, Validation and Construct Confirmatory of Core Self-Evaluations Scale. Psychol. Res. 2012, 5, 54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, R.L.; Mei, S.L.; Liang, L.L.; Zhang, Y. Relationship Between Gratitude and Internet Addiction Among College Students: The Mediating Role of Core Self-Evaluation and Meaning in Life. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2023, 39, 286–294. [Google Scholar]

- Bradburn, N. The Structure of Psychological Well-Being; Aldine: Chicago, IL, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.L.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, M.Q. Family Functioning and Emotional Health in Adolescents: Mediating Effect of Mother–Child Attachment and Its Gender Difference. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 25, 1160–1163. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. J. Educ. Meas. 2013, 51, 335–357. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Long, L.R. Statistical Remedies for Common Method Biases. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 12, 942–950. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-Report in Organizational Research: Problems and Prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Mackenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.Y. The Effect of Childhood Psychological Abuse and Neglect on Suicidal Idea in High School Students: The Mediating Role of Alexithymia and the Moderating Role of Meaning-Seeking. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 45, 1206–1213. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, X.Y.; Wang, L.J. A Pathological Model of Developmental Disorders: A Glimpse into the British Independent School of Psychopathology. J. Nanjing Xiaozhuang Univ. 2020, 36, 82–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hovens, J.G.F.M.; Giltay, E.J.; van Hemert, A.M.V.; Penninx, B.W.J.H. Childhood Maltreatment and the Course of Depressive and Anxiety Disorders: The Contribution of Personality Characteristics. Depress. Anxiety 2016, 33, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiser, S.J.; Power, H.A.; Wright, K.D. Examining the Relationships Between Childhood Abuse History, Attachment, and Health Anxiety. J. Health Psychol. 2021, 26, 1085–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Xiang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Li, Q.; Zhang, W. The Relationship Between Childhood Maltreatment and Benign/Malicious Envy Among Chinese College Students: The Mediating Role of Emotional Intelligence. J. Genet. Psychol. 2020, 147, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, K.; Wang, Y.J.; Bin, J.L.; Liu, Y.-Z. Core self-evaluation, regulatory emotional self-efficacy, and depressive symptoms: Testing two mediation models. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2016, 44, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagstaff, M.F.; del Carmen Triana, M.; Kim, S.; Al-Riyami, S. Responses to Discrimination: Relationships Between Social Support Seeking, Core Self-Evaluations, and Withdrawal Behaviors. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 54, 673–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, Y.; Sun, X.; Wang, Y.; Fang, F. Decoding Six Basic Emotions from Brain Functional Connectivity Patterns. Sci. China Life Sci. 2023, 66, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H. Advances in Understanding Neural Mechanisms of Social and Emotional Behavior. Sci. Sin. Vitae 2021, 51, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | M ± SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Gender | 1.73 ± 0.44 | 1 | ||||

| 2 Grade | 2.34 ± 1.08 | 0.009 | 1 | |||

| 3 Childhood abuse | 35.74 ± 13.76 | −0.192 ** | 0.115 ** | 1 | ||

| 4 Core self-evaluation | 34.35 ± 6.43 | −0.065 ** | −0.04 * | −0.300 ** | 1 | |

| 5 Negative affect | 1.59 ± 1.52 | 0.012 | 0.075 ** | 0.239 ** | −0.497 ** | 1 |

| 6 Suicidal ideation | 7.07 ± 2.56 | 0.006 | 0.043 ** | 0.345 ** | −0.345 ** | 0.287 ** |

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | R | R2 | F | Β | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicidal ideation | Childhood abuse | 0.345 | 0.345 | 0.345 | 0.064 | 20.44 *** |

| Core self-rating | Childhood abuse | 0.287 | 0.083 | 279.13 | −0.563 | −16.71 *** |

| Negative emotion | Childhood abuse | 0.509 | 0.259 | 543.17 | 0.053 | 7.105 *** |

| Core self-rating | −0.110 | −28.786 *** | ||||

| Suicidal ideation | Childhood abuse | 0.459 | 0.210 | 275.11 | 0.224 | 17.01 *** |

| Core self-rating | −0.082 | −10.98 *** | ||||

| Negative emotion | 0.191 | 6.125 *** |

| Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | Relative Indirect Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total indirect effect | 0.0171 | 0.0015 | 0.0144 | 0.0203 | 26.62% |

| Indirect effect 1 | 0.0116 | 0.0013 | 0.0092 | 0.0143 | 18.06% |

| Indirect effect 2 | 0.0032 | 0.0006 | 0.0021 | 0.0045 | 5.01% |

| Indirect effect 3 | 0.0023 | 0.0006 | 0.0013 | 0.0036 | 3.55% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pan, Z.; Zhang, D.; Bian, X.; Li, H. The Relationship between Childhood Abuse and Suicidal Ideation among Chinese College Students: The Mediating Role of Core Self-Evaluation and Negative Emotions. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14020083

Pan Z, Zhang D, Bian X, Li H. The Relationship between Childhood Abuse and Suicidal Ideation among Chinese College Students: The Mediating Role of Core Self-Evaluation and Negative Emotions. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(2):83. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14020083

Chicago/Turabian StylePan, Zhaoxia, Dajun Zhang, Xiaohua Bian, and Hongye Li. 2024. "The Relationship between Childhood Abuse and Suicidal Ideation among Chinese College Students: The Mediating Role of Core Self-Evaluation and Negative Emotions" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 2: 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14020083

APA StylePan, Z., Zhang, D., Bian, X., & Li, H. (2024). The Relationship between Childhood Abuse and Suicidal Ideation among Chinese College Students: The Mediating Role of Core Self-Evaluation and Negative Emotions. Behavioral Sciences, 14(2), 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14020083