Breaking the Cycle: Perceived Control and Teacher–Student Relationships Shield Adolescents from Bullying Victimization over Time

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Perceived Control and Bullying Victimization

1.2. Perceived Control and Teacher–Student Relationships

1.3. Teacher–Student Relationships and Bullying Victimization

1.4. The Current Research

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measurement Instruments

2.2.1. Bullying Victimization

2.2.2. Perceived Control

2.2.3. Teacher–Student Relationship

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlational Analysis

3.2. Trajectories of Bullying Victimization, Perceived Control, and Teacher–Student Relationships Development

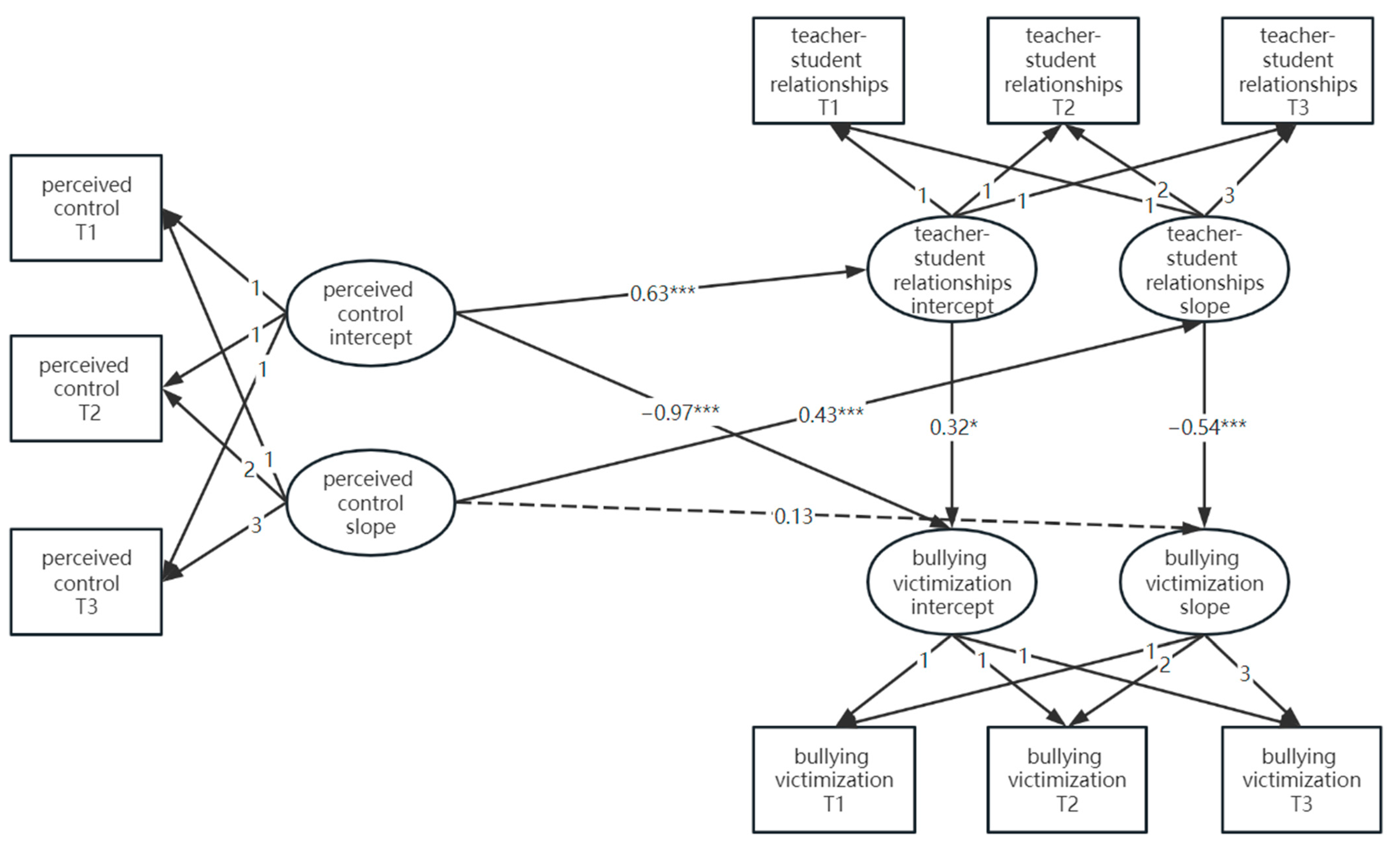

3.3. The Longitudinal Mediating Role of Teacher–Student Relationships Between Perceived Control and Bullying Victimization

4. Discussion

4.1. The Developmental Trajectories of Early Adolescent Perceived Control, Teacher–Student Relationships, and Bullying Victimization

4.2. The Longitudinal Impact of Perceived Control on Bullying Victimization

4.3. The Longitudinal Mediating Role of Teacher–Student Relationships Between Perceived Control and Bullying Victimization

5. Research Limitations, Practical Implications, and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Olweus, D. Bullying at School: What We Know and What We Can Do; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg, L. Cognitive and affective development in adolescence. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2005, 9, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroger, J. Why is identity achievement so elusive? Identity 2007, 7, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hymel, S.; Swearer, S.M. Four decades of research on school bullying: An introduction. Am. Psychol. 2015, 70, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosozawa, M.; Bann, D.; Fink, E.; Elsden, E.; Baba, S.; Iso, H.; Patalay, P. Bullying victimisation in adolescence: Prevalence and inequalities by gender, socioeconomic status, and academic performance across 71 countries. eClinicalMedicine 2021, 41, 101142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowes, L.; Maughan, B.; Ball, H.; Shakoor, S.; Ouellet-Morin, I.; Caspi, A.; Moffitt, T.E.; Arseneault, L. Chronic bullying victimization across school transitions: The role of genetic and environmental influences. Dev. Psychopathol. 2013, 25, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLara, E. Bullying Scars: The Impact on Adult Life and Relationships; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Denio, E.B.; Keane, S.P.; Dollar, J.M.; Calkins, S.D.; Shanahan, L. Children’s peer victimization and internalizing symptoms: The role of inhibitory control and perceived positive peer relationships. Merrill-Palmer Q. 2020, 66, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhoff, A.; Ribeaud, D.; Eisner, M.; Shanahan, L. Developmental trajectories of self-, other-, and dual-harm across adolescence: The role of relationships with peers and teachers. Psychopathology 2023, 56, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demol, K.; Leflot, G.; Verschueren, K.; Colpin, H. Trajectory classes of relational and physical bullying victimization: Links with peer and teacher-student relationships and social-emotional outcomes. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 51, 1354–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlechter, P.; Hellmann, J.H.; Morina, N. The longitudinal relationship between well-being comparisons and anxiety symptoms in the context of uncontrollability of worries and external locus of control: A two-wave study. Anxiety Stress Coping 2024, 37, 602–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Jin, B.; Cui, Y. Do teacher autonomy support and teacher-student relationships influence students’ depression? A 3-year longitudinal study. Collab. Innov. Cent. Assess. Basic Educ. Qual. 2022, 14, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcik, M.; Flak, W.; Leśniewski, J. Downward spiral of bullying: Victimization timeline from former victims’ perspective. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP10985–NP11008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kay, A.C.; Whitson, J.A.; Gaucher, D.; Galinsky, A.D. Compensatory control: Achieving order through the mind, our institutions, and the heavens. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 18, 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenny, O.A. Low self-control and school bullying: Testing the GTC in Nigerian sample of middle school students. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP11386–NP11412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Lee, J.R. Impacts of low self-control and delinquent peer associations on bullying growth trajectories among Korean youth: A latent growth mixture modeling approach. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, NP4139–NP4169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awaworyi Churchill, S.; Smyth, R. Locus of control and the mental health effects of local area crime. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 301, 114910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, S.N.; Ioannou, M.; Stavrinides, P. Parenting styles and bullying at school: The mediating role of locus of control. Int. J. Sch. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 5, 226–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Tian, L. Bullying victimization and developmental trajectories of internalizing and externalizing problems: The moderating role of locus of control among children. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2021, 49, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotter, J.B. Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychol. Monogr. Gen. Appl. 1966, 80, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliday, S.; Gregory, T.; Taylor, A.; Digenis, C.; Turnbull, D. The impact of bullying victimization in early adolescence on subsequent psychosocial and academic outcomes across the adolescent period: A systematic review. J. Sch. Violence 2021, 20, 351–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudasill, K.M.; Rimm-Kaufman, S.E. Teacher-child relationship quality: The roles of child temperament and teacher-child interactions. Early Child Res. Q. 2009, 24, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, K.M.; Spinrad, T.L.; Eisenberg, N.; Sulik, M.J.; Valiente, C.; Huerta, S.; Edwards, A.; Eggum, N.D.; Kupfer, A.S.; Lonigan, C.J.; et al. Relations of children’s effortful control and teacher-child relationship quality to school attitudes in a low-income sample. Early Educ. Dev. 2011, 22, 434–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, F.; Chen, J.; Torney-Purta, J. Profiles of adolescents’ perceptions of democratic classroom climate and students’ influence: The effect of school and community contexts. J. Youth Adolesc. 2018, 47, 1279–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakadorova, O.; Raufelder, D. The essential role of the teacher-student relationship in students’ need satisfaction during adolescence. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2018, 58, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moller, A.C.; Deci, E.L.; Elliot, A.J. Person-level relatedness and the incremental value of relating. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 36, 754–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, C.; Schwarz, D.S.; Kollerová, L. Teachers can make a difference in bullying: Effects of teacher interventions on students’ adoption of bully, victim, bully-victim, or defender roles across time. J. Youth Adolesc. 2022, 51, 2312–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, H.A. Conceptualizing the role and influence of student-teacher relationships on children’s social and cognitive development. Educ. Psychol. 2003, 38, 207–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschueren, K.; Koomen, H.M.Y. Teacher-child relationships from an attachment perspective. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2012, 14, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demol, K.; Leflot, G.; Verschueren, K.; Colpin, H. Revealing the transactional associations among teacher-child relationships, peer rejection, and peer victimization in early adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 2020, 49, 2311–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H. The situation and influencing factors of 15-year-old school students’ bullying in China: Based on the analysis of PISA 2015 data from four provinces and cities in China. Educ. Sci. Res. 2017, 11, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- ten Bokkel, I.M.; Verschueren, K.; Demol, K.; van Gils, F.E.; Colpin, H. Reciprocal links between teacher-student relationships and peer victimization: A three-wave longitudinal study in early adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 2166–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ten Bokkel, I.M.; Roorda, D.L.; Maes, M.; Verschueren, K.; Colpin, H. The role of affective teacher-student relationships in bullying and peer victimization: A multilevel meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2023, 52, 110–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bear, G.G.; Yang, C.; Mantz, L. Technical Manual for the Delaware School Survey; University of Delaware: Newark, DE, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, J.; Huang, S. Revision of Chinese version of Delaware Bullying Victimization Scale-student in adolescents. Econ. Manag. Coll. Guangzhou Univ. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2018, 26, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachman, M.E.; Weaver, S.L. The sense of control as a moderator of social class differences in health and well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, R.; Guo, Y. Is materialism all that bad? Challenges from empirical and conceptual research. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 25, 1811–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianta, R.C. Manual and Scoring Guide for the Student-Teacher Relationship Scale; University of Virginia: Charlottesville, VA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Z.; Zhao, Y. The characteristics of teacher-student relationships and its relationship with school adjustment of students. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2007, 23, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, J.S.; Midgley, C.; Wigfield, A.; Buchanan, C.M.; Reuman, D.; Flanagan, C.; Mac Iver, D. Development during adolescence: The impact of stage-environment fit on young adolescents’ experiences in schools and in families. Am. Psychol. 1993, 48, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J.S.; Roeser, R.W. Schools, academic motivation, and stage-environment fit. In Handbook of Adolescent Psychology: Individual Bases of Adolescent Development, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 404–434. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A.; Barbaranelli, C.; Caprara, G.V.; Pastorelli, C. Self-efficacy beliefs as shapers of children’s aspirations and career trajectories. Child Dev. 2001, 72, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engels, M.C.; Colpin, H.; Van Leeuwen, K.; Bijttebier, P.; Van Den Noortgate, W.; Claes, S.; Goossens, L.; Verschueren, K. Behavioral engagement, peer status, and teacher-student relationships in adolescence: A longitudinal study on reciprocal influences. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 1192–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, A.; Hofkens, T.L.; Pianta, R.C. Teacher-student relationships across the first seven years of education and adolescent outcomes. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 71, 101200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirtas-Zorbaz, S.; Ergene, T. School adjustment of first-grade primary school students: Effects of family involvement, externalizing behavior, teacher and peer relations. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 101, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Z.; Sun, Y. Difference between cognitive empathy and affective empathy in development: Meta-analysis preliminary exploration. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2021, 37, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, B.; Finkelstein, B.D.; Betts, N.T. A developmental meta-analysis of peer conflict resolution. Dev. Rev. 2001, 21, 423–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulig, T.C.; Pratt, T.C.; Cullen, F.T.; Chouhy, C.; Unnever, J.D. Explaining bullying victimization: Assessing the generality of the low self-control/risky lifestyle model. Vict. Offenders 2017, 12, 891–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.S.; Park, J.H. The effects of school violence victimization on cyberbullying perpetration in middle school students and the moderating role of self-control. Korean J. Child Stud. 2016, 37, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terranova, A.; Harris, J.; Kavetski, M.; Oates, R. Responding to peer victimization: A sense of control matters. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2011, 40, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unnever, J.D.; Cornell, D.G. Bullying, self-control, and ADHD. J. Interpers. Violence 2003, 18, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Cheung, S.-F.; Chio, J.H.-M.; Chan, M.-P.S. Cultural meaning of perceived control: A meta-analysis of locus of control and psychological symptoms across 18 cultural regions. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2013, 139, 152–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Xu, J.; Gao, Y. Bullying victimization, coping strategies, and depression of children of China. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, 195–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Aalst, D.A.E.; Huitsing, G.; Mainhard, T.; Cillessen, A.H.N.; Veenstra, R. Testing how teachers’ self-efficacy and student-teacher relationships moderate the association between bullying, victimization, and student self-esteem. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2021, 18, 928–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Hui, Z.; Bai, W.; Terry, P.; Ma, M.; Li, Y.; Cheng, L.; Gu, W.; Wang, M. The mediating effect of regulatory emotional self-efficacy on the association between self-esteem and school bullying in middle school students: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, A.G.; Zane, N.W.S. Ethnic differences in coping with interpersonal stressors: A test of self-construals as cultural mediators. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2004, 35, 446–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.; Valiente, C.; Eggum, N.D. Self-regulation and school readiness. Early Educ. Dev. 2010, 21, 681–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, K.D. Ostracism. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 425–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greitemeyer, T.; Sagioglou, C. Subjective socioeconomic status causes aggression: A test of the theory of social deprivation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 111, 178–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reavis, R.D.; Keane, S.P.; Calkins, S.D. Trajectories of peer victimization: The role of multiple relationships. Merrill-Palmer Q. 2010, 56, 303–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serdiouk, M.; Berry, D.; Gest, S.D. Teacher-child relationships and friendships and peer victimization across the school year. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 46, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliot, M.; Cornell, D.; Gregory, A.; Fan, X. Supportive school climate and student willingness to seek help for bullying and threats of violence. J. Sch. Psychol. 2010, 48, 533–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.; Nguyen, H.M.T.; Ha, T.T.; Nguyen, N.N. The role of teacher and peer support against bullying among secondary school students in Vietnam. J. Genet. Psychol. 2022, 183, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Chan, M.K.; Ma, T.L. School-wide social emotional learning (SEL) and bullying victimization: Moderating role of school climate in elementary, middle, and high schools. J. Sch. Psychol. 2020, 82, 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ryzin, M.J.; Roseth, C.J. Cooperative Learning in Middle School: A Means to Improve Peer Relations and Reduce Victimization, Bullying, and Related Outcomes. J. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 110, 1192–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. bullying victimization T1 | 21.83 | 8.28 | ||||||||

| 2. bullying victimization T2 | 19.67 | 7.31 | 0.46 *** | |||||||

| 3. bullying victimization T3 | 19.23 | 6.82 | 0.36 *** | 0.46 *** | ||||||

| 4. perceived control T1 | 55.34 | 9.09 | −0.33 *** | −0.21 *** | −0.16 *** | |||||

| 5. perceived control T2 | 55.72 | 9.74 | −0.31 *** | −0.28 *** | −0.28 *** | 0.56 *** | ||||

| 6. perceived control T3 | 55.92 | 9.69 | −0.28 *** | −0.24 *** | −0.27 *** | 0.46 *** | 0.60 *** | |||

| 7. teacher–student relationships T1 | 68.77 | 9.52 | −0.20 *** | −0.12 *** | −0.07 *** | 0.31 *** | 0.24 *** | 0.23 *** | ||

| 8. teacher–student relationships T2 | 70.41 | 9.27 | −0.13 *** | −0.19 *** | −0.14 *** | 0.22 *** | 0.32 *** | 0.32 *** | 0.43 *** | |

| 9. teacher–student relationships T3 | 71.22 | 9.22 | −0.17 *** | −0.17 *** | −0.14 *** | 0.18 *** | 0.26 *** | 0.42 *** | 0.36 *** | 0.51 *** |

| Intercept | Slope | r (Intercept with Slope) | Model Fit | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Variance | Mean | Variance | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR | ||

| bullying victimization | 21.29 *** | 36.40 *** | −0.69 *** | 6.69 | −0.15 | 0.98 | 0.92 | 0.05 | 0.02 |

| perceived control | 54.73 *** | 47.86 *** | 0.57 *** | 15.68 *** | −0.26 | 1.00 | 1.00 | <0.01 | 0.01 |

| teacher–student relationships | 68.98 *** | 43.94 *** | 0.98 *** | 8.64 *** | −0.31 ** | 0.98 | 0.95 | 0.07 | 0.02 |

| Mediating Effect | β | SE | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept: Perceived control → Teacher–student relationships → Bullying victimization | 0.20 | 0.10 | [0.07, 0.45] |

| Slope: Perceived control → Teacher–student relationships → Bullying victimization | −0.23 | 0.52 | [−0.60, −0.10] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Z.; Lu, K.; Wang, X.; Zheng, J.; Gao, X.; Fan, Q. Breaking the Cycle: Perceived Control and Teacher–Student Relationships Shield Adolescents from Bullying Victimization over Time. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 1198. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121198

Wang Z, Lu K, Wang X, Zheng J, Gao X, Fan Q. Breaking the Cycle: Perceived Control and Teacher–Student Relationships Shield Adolescents from Bullying Victimization over Time. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(12):1198. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121198

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Zhongjie, Kaiyuan Lu, Xuezhen Wang, Juanjuan Zheng, Xinyi Gao, and Qianqian Fan. 2024. "Breaking the Cycle: Perceived Control and Teacher–Student Relationships Shield Adolescents from Bullying Victimization over Time" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 12: 1198. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121198

APA StyleWang, Z., Lu, K., Wang, X., Zheng, J., Gao, X., & Fan, Q. (2024). Breaking the Cycle: Perceived Control and Teacher–Student Relationships Shield Adolescents from Bullying Victimization over Time. Behavioral Sciences, 14(12), 1198. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121198