1. Introduction

With increasing specialization in medicine and the growing complexity of healthcare delivery systems, interest in integrating leadership and teamwork training into medical education has increased significantly [

1]. Physicians must not only treat patients using their knowledge and skills but also act as leaders who communicate with and guide multidisciplinary healthcare teams, hospital departments, patients and their families, and fellow doctors. As a result, they are increasingly required to possess not only individual abilities but also competencies such as communication, teamwork, organizational skills, consideration, and service within a team context. These competencies are closely linked to leadership training [

2]. Ford et al. [

3] detail the intricate relationship between leadership and teamwork in the healthcare environment and emphasize that team efficiency is inextricably linked to patient safety outcomes. They also suggest that clinical training, including simulation exercises, is a representative example of team-based activities and is considered a form of leadership training in medical schools.

Some medical schools abroad have recognized the importance of leadership and have integrated leadership training into their curricula [

4,

5,

6]. However, determining the specifics of the training to be implemented and how it should be carried out in medical schools still poses a challenge. This dilemma arises because the best approach to leadership education is to provide students with practical experiences rather than mere theoretical instruction. Several medical schools in South Korea also have curricula focused on developing leadership competencies, ultimately emphasizing communication and teamwork [

7,

8]. These leadership courses utilize various methods, including lectures, discussions, workshops, student presentations, written assignments, hospital experiences, and volunteer activities, all of which involve direct student participation. However, a review of the leadership education currently implemented in medical schools reveals that the number of programs related to sports activities is limited [

9]. Research on general physical education (PE) programs at universities is also restricted to topics such as the development of a healthy self-identity [

10], interpersonal relationships [

11], and adjustment to university life [

12].

This study provides a phenomenological exploration of the internal changes in teamwork and leadership among students at the University of Ulsan College of Medicine (UUCM) who participated in leadership training through team sports, specifically through rowing. Rowing emphasizes teamwork and requires a strong sense of commitment to the team [

9]. Schools that participate in rowing competitions as intercollegiate events include Oxford and Cambridge, Harvard and Yale, and Waseda and Keio universities internationally, as well as Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, and Yonsei University in South Korea.

The educational goal of UUCM is to “cultivate future leaders who will lead the medical field”. To achieve this goal, a new curriculum was developed and implemented in 2022, which includes a leadership course utilizing rowing exercises. This study aims to discover the subjective experiences of second-year pre-medical students who participated in a rowing exercise class by analyzing the reflection journals they submitted as part of a leadership program. By understanding the students’ experiences in the rowing exercise class, the study seeks to derive implications for leadership education in medical schools.

2. Research Methodology

2.1. Study Participants

This study involved 40 second-year premedical students who participated in a leadership course from 23 May to 11 June 2022. After completing the rowing exercise, the students were asked to submit a reflective journal, approximately two A4 pages long, in which they freely expressed their thoughts on the rowing exercise. All 40 students submitted their reflective journals, which were subsequently analyzed.

2.2. Overview of the Rowing Exercise Course

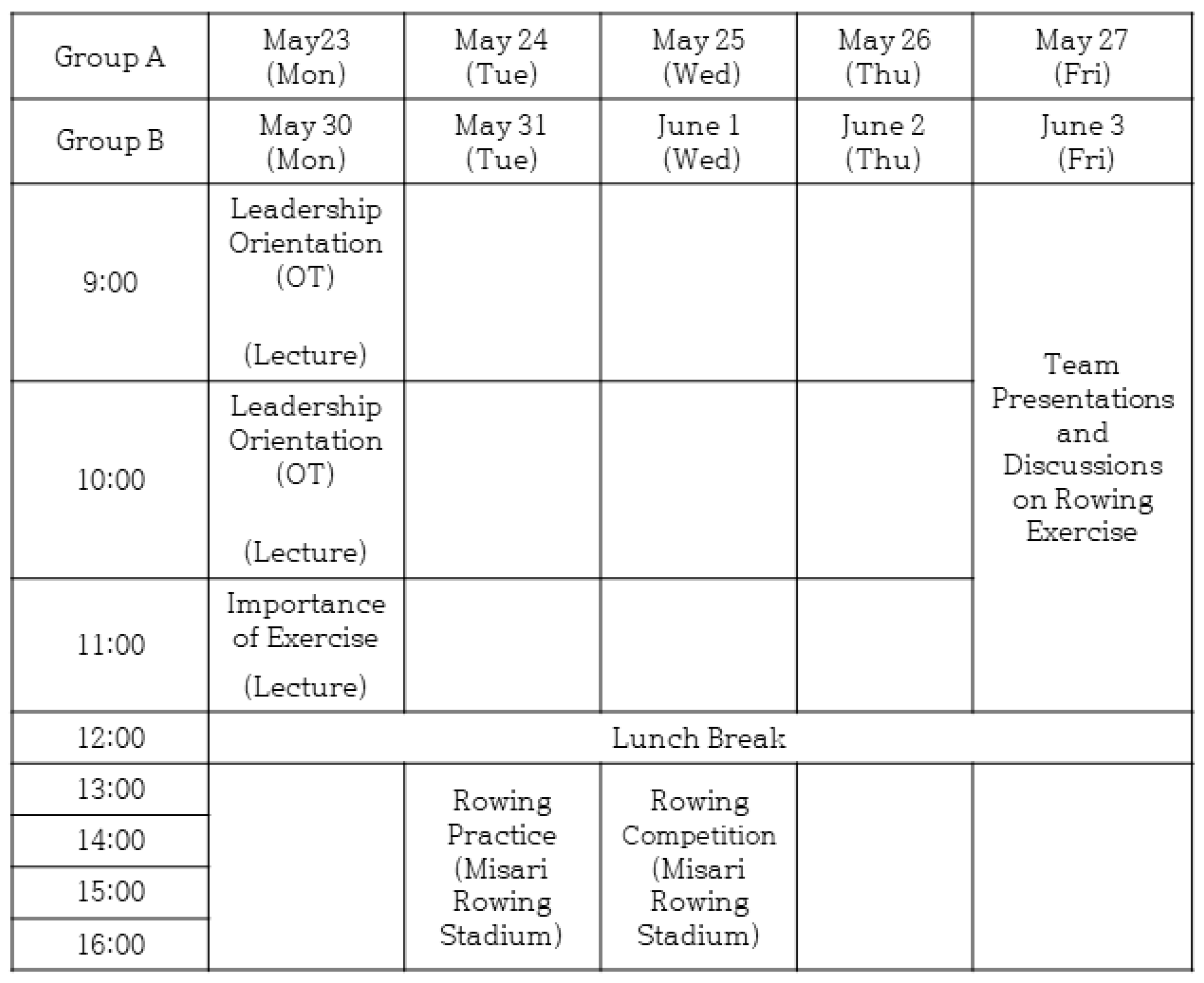

UUCM is committed to its mission of “continuously striving for the healthy lives of humanity” and aims to cultivate medical leaders equipped with communication, ethics, and creativity skills. Since 2022, UUCM has implemented a new curriculum under the motto “Less Competitive, More Excellence” (LCME). This curriculum focuses on avoiding unnecessary and unproductive competition while fostering the essential competencies required of a good physician. An 11-week humanities and social sciences course is conducted for second-year premedical students, with the leadership course spanning two weeks. The content and schedule of the rowing exercise conducted as part of the leadership course are depicted in

Figure 1.

The rowing exercise was conducted as part of the leadership course. The students were divided into Groups A and B, with 20 in each, and the exercise was conducted over one week for each group at the Misari Rowing Stadium. On the first day, the students attended a theoretical class on the importance of exercise and the history and techniques of rowing. On the second day, the students experienced a rowing machine workout at the Misari Rowing Stadium, along with warm-up exercises. The rowing machine was used indoors for aerobic and strength training to maintain the necessary sensations for rowing. On the third day, the students were divided into five teams to participate in a rowing practice session. Before boarding the boat, the students chose their roles freely (cox, seats 1, 2, 3, 4). After practicing rowing, they participated in team-based rowing races. On the final day of the course, the students submitted their reflective journals and participated in group presentations to share their thoughts and experiences.

2.3. Data Analysis

This study utilized Colaizzi’s phenomenological analysis procedure to understand and structure students’ experiences with the rowing exercise [

13]. Colaizzi’s phenomenological analysis is a methodology employed by researchers to systematically analyze phenomenological data, aiming to understand the subjective experiences of research participants. The procedure involves several key steps: initially, meaningful statements related to the research phenomenon are identified and meanings are derived from these statements. Subsequently, these meanings are categorized, with the themes synthesized and integrated. Finally, the essential structure of the phenomenon is articulated as revealed through the research. In this study, Colaizzi’s method guided the data analysis, encompassing the phases of familiarization, meaning extraction, meaning clustering and thematization, and structure development [

14].

Familiarization: Both researchers, experienced in qualitative research and phenomenological analysis, independently read and re-read all 40 reflective journals to capture the overall sentiment and identify key themes.

Meaning Extraction: Meaningful statements relating to the rowing experience and the development of leadership and teamwork were extracted from each journal. A detailed coding scheme was developed and consistently applied by both researchers.

Meaning Clustering and Thematization: Similar statements were grouped into clusters of meanings, which were then synthesized into broader themes. Any disagreements regarding the categorization of meanings and themes were resolved through discussion and consensus.

Structure Development: The themes were systematically integrated to construct an essential structure that reflects the comprehensive phenomenological experience of the rowing exercise, focusing on attitudes prior to the course, factors enhancing teamwork, hindering factors, and reflections following the course.

2.4. Ensuring Trustworthiness

To enhance the trustworthiness of the qualitative research findings, this study utilized prolonged engagement, triangulation, audit trail, and reflexivity.

Prolonged Engagement: To gain a deeper understanding of students’ experiences in the rowing-based leadership program and enhance data richness, the researchers participated in the two-week program, conducting an in-depth analysis of students’ reflective journals. This immersive approach facilitated a more precise understanding of students’ experiences and the transformative process they underwent.

Triangulation: To ensure trustworthiness, this study employed inter-rater reliability through triangulation. Two researchers with extensive experience in qualitative research independently analyzed the reflective journals. The researchers compared their individual analyses, identifying points of congruence and divergence. Disagreements were resolved through thorough discussion and consensus-building.

Audit Trail: To ensure transparency, a detailed research log was maintained, documenting the research questions, the literature review, phenomenological methodology, and the data analysis process (including data analysis records, coding, and interpretations). Furthermore, the coding data used in the study were made publicly available on the FigShare online repository to allow for scrutiny and potential use by other researchers.

Reflexivity: The researchers actively mitigated the potential influence of personal biases and values on the research findings. Regular research meetings facilitated the sharing of research processes and results, along with reciprocal feedback.

4. Discussion

The Association of American Medical Colleges [

15] emphasizes the growing importance of leadership development in medical schools, stating that “leadership development has become more crucial than ever to anticipate, navigate, and address the complex challenges faced by medical schools and teaching hospitals today”. While numerous medical schools have developed and implemented leadership training programs focusing on communication and teamwork enhancement [

16,

17], the utilization of sports, particularly rowing, as a vehicle for leadership development represents a novel and underexplored approach in medical education.

The study analyzed the reflective journals written by pre-medical students who participated in rowing exercise classes conducted as part of a leadership course to understand their subjective experiences of the rowing classes. The analysis revealed the following results: first, before the rowing exercise course, students did not fully appreciate the value of incorporating physical activity into their medical education. Students viewed the course as a stress-free break from studying, that is, a time to relax and have fun. They felt a sense of anticipation and excitement about trying a sport they had never experienced. Meanwhile, they were also concerned about not performing well and whether the exercise might be too physically demanding. In addition, some dissatisfaction was expressed about why such a sport was included in the medical school curriculum. Medical students lead competitive lives even before entering medical school, particularly in preparation for their admission. After entering medical school, students experience significant amounts of coursework, pressure to maintain high grades, feelings of relative failure, and academic stress due to intense competition [

18]. They also often suffer from issues such as sleep deprivation and chronic fatigue [

19]. Previous research [

20] documents that medical students’ perfectionist tendencies lead them to set excessively high standards for themselves and to strive for perfection. Furthermore, they tend to be highly self-critical when they fail to meet these standards.

According to previous studies [

21], sports education can contribute to students’ health as well as their interpersonal relationships, personal psychosocial skills, and professionalism. Therefore, there is a need for educational programs that promote mental and physical health for medical students who are exposed to competition and experience high levels of stress. However, to date, there has been a lack of basic research in South Korea on how much physical activity education medical students are engaging in at university and what types of exercise classes are included in the official curriculum. It is necessary to provide reasons as to why educational programs focused on physical activity are needed for medical students, as well as to design effective educational plans for the implementation of these programs. Additionally, follow-up studies should be conducted on the effectiveness of educational programs utilizing sports in medical education.

Second, through their participation in the rowing program, students gained a deeper understanding of the factors that both foster and impede effective teamwork. In their reflective journals, the factors that enhanced teamwork included communication, trust and consideration, and a sense of responsibility, while the hindering factors were competitiveness and impatience, arrogance about individual ability, and avoidance of responsibility. Rowing is characterized by the fact that the boat can only move forward through cooperation and harmony; no matter how skilled someone is, they cannot move the boat on their own. The rowing course allowed even students accustomed to individualism to reflect on how working together could lead to greater efficiency and the ability to go further. Similarly, our findings align with those of Yang [

9], who also investigated rowing exercises at a medical school. Students developed a sense of community as they synchronized their movements, thereby fostering a mindset of consideration and respect for one another. In addition, in team-based general PE courses at universities, students developed confidence in their ability to complete tasks with their peers, which led to improved academic performance [

22].

Our findings strongly suggest that integrating team sports, such as rowing, into medical education curricula can significantly enhance students’ collaborative skills and their capacity to achieve collective goals, potentially improving their performance in multidisciplinary healthcare teams. Because non-cognitive competencies such as communication, trust and respect, and responsibility are difficult to develop in a short period, there is a need for a curriculum that can systematically cultivate non-cognitive abilities that medical students should possess through various activities, including team sports.

Third, through their rowing experience, students developed a new perspective on leadership. They learned that effective leadership emphasizes collaboration and teamwork, with the leader’s role being to facilitate collective effort and progress rather than to rely solely on individual skills. The leader’s role is even more critical in a rowing race because multiple individuals must work together to move the boat. The situation is similar for physicians, who need to collaborate with various professionals. Wiseman et al. [

2] identified critical leadership competencies essential for residency training, encompassing responsibility, teamwork, moral integrity, and empathy, which align with the skills fostered through the rowing exercise. Additionally, Stillman [

23], who studied the relationship between leadership and team performance, reported that leadership is a critical element for the success of an organization and is important for medical staff collaborating with various professions, positively impacting team performance.

Leadership is often defined as the skill of exerting influence over others to motivate them toward achieving a common goal [

24]. To date, most studies on leadership in medical schools have concentrated on self-leadership [

25], which focuses on motivating oneself and taking responsibility through autonomy and self-control, ultimately exerting influence over one’s actions and decisions. However, shared leadership emphasizes the roles of the entire team rather than a single leader. Shared leadership is one of the leadership approaches adopted by many organizations to address the complexities of modern organizations, referring to a team phenomenon where the role and influence of the leader are distributed among team members [

26].

The study found that students experienced the importance of mutual influence among members for the group’s goals rather than individual achievement through the rowing exercise class. In other words, students showed a shift in the concept of leadership, valuing the ‘team’ over ‘self’ through the rowing exercise. In rowing, each team member is assigned specific roles and responsibilities. Students found that while individual abilities are important for maximizing team effectiveness, trust among team members who can achieve common goals and tasks together is crucial. The rowing class provided students with an opportunity to reflect on how the team can grow and develop through mutual feedback from team members. In medical education, shared leadership has traditionally been studied in clinical settings such as emergency situations or simulation training [

27]. This is because simulation training is similar to a sport in which multiple team members work together towards the common goal of patient safety. However, the results of this study indicate that leadership skills in medical students can be developed not only through simulation training limited to clinical practice but also through team sports. Medical schools need to develop and implement curricula that incorporate a variety of activities, including team sports, to provide more meaningful leadership education.

The significance of our study lies in its demonstration of the potential of rowing as a team sport to serve as an effective program for fostering teamwork and leadership within the medical school curriculum. As this study only analyzed the reflective journals of second-year premedical students from a single university who participated in the rowing exercise course, it has limitations in terms of generalizing the results. Future research should analyze students’ experiences using various methods, including not only the analysis of reflective journals but also student interviews and surveys. Moreover, the experiences of students at other medical schools that have incorporated various team sports into their curricula need to be investigated, and the findings used to inform the development of medical education programs.