Parent–Child Relationships and Adolescents’ Non-Cognitive Skills: Role of Social Anxiety and Number of Friends

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Parent–Child Relationship and Adolescents’ Non-Cognitive Skills

2.2. Mediating Effect of Number of Friends

2.3. Mediating Effect of Social Anxiety

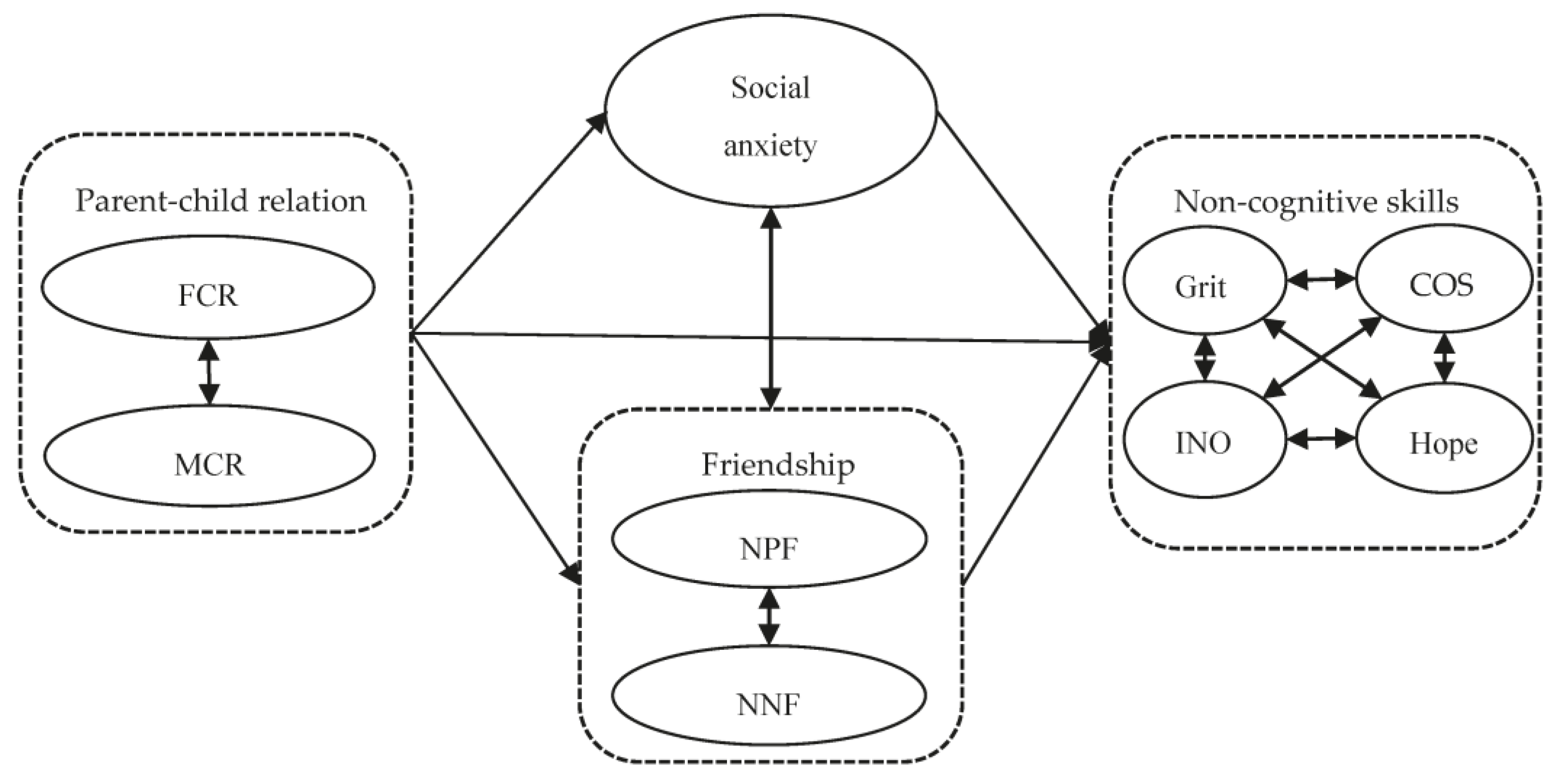

2.4. Research Hypotheses

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Subjects

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Parent–Child Relationships

3.2.2. Non-Cognitive Skills

3.2.3. Social Anxiety Scale of Children (SASC)

3.2.4. Number of Friends

3.3. Procedure

3.4. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Direct Effect

4.3. Mediation Model Testing

5. Discussion

6. Implications

7. Limitations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, Y.; Afari, E.; Khine, M.S. Effect of Non-Cognitive Factors on Academic Achievement among Students in Suzhou: Evidence from OECD SSES Data. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2023, 38, 1643–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautz, T.; Heckman, J.J.; Diris, R.; Ter Weel, B.; Borghans, L. Fostering and Measuring Skills: Improving Cognitive and Non-Cognitive Skills to Promote Lifetime Success. 2014. Available online: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w20749/w20749.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2024).

- Heckman, J.J.; Kautz, T. Fostering and Measuring Skills: Interventions that Improve Character and Cognition. In The Myth of Achievement Tests: The GED and the Role of Character in American Life; Heckman, J.J., Humphries, J.E., Kautz, T., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2014; pp. 341–430. [Google Scholar]

- Humphries, J.E.; Kosse, F. On the Interpretation of Non-Cognitive Skills–What is Being Measured and Why It Matters. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2017, 136, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutman, L.M.; Schoon, I. The Impact of Non-Cognitive Skills on Outcomes for Young People; Education Endowment Foundation: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, H.; Miyatake, N.; Kusaka, T. Non-Cognitive Skills and the Parent–Child Relationship: A Cross-Sectional Study. Preprints 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veas, A.; Castejón, J.L.; Gilar, R.; Miñano, P. Academic Achievement in Early Adolescence: The Influence of Cognitive and Non-Cognitive Variables. J. Gen. Psychol. 2015, 142, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Li, Z.Y. Effect of Preschool Experience on Non-Cognitive Skills in Junior Middle School Students: An Empirical Study Based on CEPS. Educ. Econ. 2018, 4, 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Zhao, W.L.; Bian, W.J. Empirical Study of the Influence of Family Background on Non-Cognitive Skills. Educ. Dev. Stud. 2017, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Bowles, S.; Gintis, H. Schooling in Capitalist America; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- McGue, M.; Willoughby, E.A.; Rustichini, A.; Johnson, W.; Iacono, W.G.; Lee, J.J. The Contribution of Cognitive and Noncognitive Skills to Intergenerational Social Mobility. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 31, 835–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smithers, L.G.; Sawyer, A.C.; Chittleborough, C.R.; Davies, N.M.; Davey Smith, G.; Lynch, J.W. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Effects of Early Life Non-Cognitive Skills on Academic, Psychosocial, Cognitive and Health Outcomes. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2018, 2, 867–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, J.L. School-Based Practices for the 21st Century: Noncognitive Factors in Student Learning and Psychosocial Outcomes. Policy Insights Behav. Brain Sci. 2020, 7, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckman, J.J.; Kautz, T.D. Achievement Tests and the Role of Character in American Life. In The Myth of Achievement Tests: The GED and the Role of Character in American Life; Heckman, J.J., Humphries, J.E., Kautz, T., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2014; pp. 1–71. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, B.W.; DelVecchio, W.F. The rank-order consistency of personality traits from childhood to old age: A quantitative review of longitudinal studies. Psychol. Bull. 2000, 126, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tottenham, N.; Galván, A. Stress and the adolescent brain: Amygdala-prefrontal cortex circuitry and ventral striatum as developmental targets. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 70, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, S.; Gu, Q.; Lei, Y.; Shen, J.; Niu, Q. Can physical exercise promote the development of teenagers’ non-cognitive ability? —Evidence from China education panel survey (2014–2015). Children 2022, 9, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Chen, B. Parental migration and non-Cognitive abilities of left-Behind children in rural China: Causal effects by an instrumental variable approach. Child Abus. Negl. 2022, 123, 105389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Tang, X.; Yang, H.; Liu, Y. Parental Marriage and the Non-Cognitive Abilities of Infants and Toddlers: Survey Findings from China Family Panel Studies. Econ. Hum. Biol. 2023, 50, 101272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, L.; Tong, T. Parenting Style and the development of on cognitive ability in Children. China Econ. Rev. 2020, 62, 101477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grätz, M.; Lang, V.; Diewald, M. The ffects of arenting on arly dolescents’ oncognitive kills: Evidence from a ample of wins in Germany. Acta Sociol. 2022, 65, 398–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Bono, E.; Kinsler, J.; Pavan, R. Skill ormation and the rouble with Child on-ognitive kill easures. IZA Discuss. Pap. 2020, 13713. [Google Scholar]

- Kretzschmar, A.; Wagner, L.; Gander, F.; Hofmann, J.; Proyer, R.T.; Ruch, W. Character trengths and luid ntelligence. J. Pers. 2022, 90, 1057–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harzer, C.; Bezuglova, N.; Weber, M. NCSsemental alidity of haracter trengths as redictors of ob erformance eyond eneral ental bility and the ig ive. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 518369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, L. Good character is what we look for in a friend: Character strengths are positively related to peer acceptance and friendship quality in early adolescents. J. Early Adolesc. 2019, 39, 864–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, W.P.; Li, Z.Y. The Impact of Non-cognitive Skills on Junior High School Students’ Academic Achievement: An Empirical Analysis Based on CEPS. J. Cent. China Norm. Univ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2021, 60, 154–163. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U.; Morris, P.A. The Bioecological Model of Human Development. In Handbook of Child Psychology: Theoretical Models of Human Development; Damon, W., Lerner, R.M., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 793–828. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, I.W.; Ryan, C.E.; Keitner, G.I.; Bishop, D.S.; Epstein, N.B. The McMaster Approach to Families: Theory, Assessment, Treatment and Research. J. Fam. Ther. 2000, 22, 168–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedro, M.F.; Ribeiro, T.; Shelton, K.H. Romantic Attachment and Family Functioning: The Mediating Role of Marital Satisfaction. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2015, 24, 3482–3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Weiser, D.A.; Fischer, J.L. Self-Efficacy, Parent–Child Relationships, and Academic Performance: A Comparison of European American and Asian American College Students. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2016, 19, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Halty, M.; Salanova, M.; Schaufeli, W.B. The Strengthening Starts at Home: Parent–Child Relationships, Psychological Capital, and Academic Performance—A Longitudinal Mediation Analysis. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 3788–3796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerns, K.A.; Stevens, A.C. Parent-Child Attachment in Late Adolescence: Links to Social Relations and Personality. J. Youth Adolesc. 1996, 25, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Liu, X. Understanding the Role of Parent–Child Relationships in Conscientiousness and Neuroticism Development among Chinese Middle School Students: A Cross-Lagged Model. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhou, Z.; Gu, C.; Lei, Y.; Fan, C. Family Socio-Economic Status and Parent-Child Relationships Are Associated with the Social Creativity of Elementary School Children: The Mediating Role of Personality Traits. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2018, 27, 2999–3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, T.A.; Rijsdijk, F.V.; Narusyte, J.; Ganiban, J.M.; Reiss, D.; Spotts, E.; Eley, T.C. Associations Between the Parent–Child Relationship and Adolescent Self-Worth: A Genetically Informed Study of Twin Parents and Their Adolescent Children. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2017, 58, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, P.A.; Le Brocque, R.; Hammen, C. Maternal Depression, Parent–Child Relationships, and Resilient Outcomes in Adolescence. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2003, 42, 1469–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Liu, L.; Shan, N. Parent–Child Relationships and Resilience Among Chinese Adolescents: The Mediating Role of Self-Esteem. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoeve, M.; Dubas, J.S.; Eichelsheim, V.I.; Van der Laan, P.H.; Smeenk, W.; Gerris, J.R. The relationship between parenting and delinquency: A meta-analysis. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2009, 37, 749–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, S.; Wu, X.; Li, X. Coparenting Behavior, Parent–Adolescent Attachment, and Peer Attachment: An Examination of Gender Differences. J. Youth Adolesc. 2020, 49, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorrese, A.; Ruggieri, R. Peer Attachment: A Meta-analytic Review of Gender and Age Differences and Associations with Parent Attachment. J. Youth Adolesc. 2012, 41, 650–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, W.A.; Laursen, B. Parent-adolescent Relationships and Influences. Handb. Adolesc. Psychol. 2004, 331, 331–361. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, L.G.; Coatsworth, J.D.; Greenberg, M.T. A Model of Mindful Parenting: Implications for Parent–child Relationships and Prevention Research. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 12, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldrip, A.M.; Malcolm, K.T.; Jensen-Campbell, L.A. With a Little Help from Your Friends: The Importance of High-quality Friendships on early Adolescent Adjustment. Soc. Dev. 2008, 17, 832–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, C.M.; Wentzel, K.R. Friend Influence on Prosocial Behavior: The Role of Motivational Factors and Friendship Characteristics. Dev. Psychol. 2006, 42, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gest, S.D.; Graham-Bermann, S.A.; Hartup, W.W. Peer Experience: Common and Unique Features of Number of Friendships, Social Network Centrality, and Sociometric Status. Soc. Dev. 2001, 10, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, K.E.; Ladd, G.W. Connectedness and Autonomy Support in Parent–child Relationships: Links to Children’s Socioemotional Orientation and Peer Relationships. Dev. Psychol. 2000, 36, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.; Friedlander, M.; Pieterse, A.L. Contributions of Acculturation, Enculturation, Discrimination, and Personality Traits to Social Anxiety Among Chinese Immigrants: A Context-specific Assessment. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2016, 22, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contractor, R.; Sarkar, S. Understanding the Relationship between Social Anxiety and Personality. Indian J. Ment. Health 2018, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costache, M.E.; Frick, A.; Månsson, K.; Engman, J.; Faria, V.; Hjorth, O.; Furmark, T. Higher-and Lower-order Personality Traits and Cluster Subtypes in Social Anxiety Disorder. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, J.; Wang, A.; Qian, M.; Zhang, L.; Gao, J.; Yang, J.; Chen, P. Shame, Personality, and Social Anxiety Symptoms in Chinese and American Nonclinical Samples: A cross-cultural study. Depress. Anxiety 2008, 25, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welander-Vatn, A.; Torvik, F.A.; Czajkowski, N.; Kendler, K.S.; Reichborn-Kjennerud, T.; Knudsen, G.P.; Ystrom, E. Relationships Among Avoidant Personality Disorder, Social Anxiety Disorder, and Normative Personality Traits: A Twin Study. J. Personal. Disord. 2019, 33, 289–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karsten, J.; Penninx, B.W.; Riese, H.; Ormel, J.; Nolen, W.A.; Hartman, C.A. The State Effect of Depressive and Anxiety Disorders on Big Five Personality Traits. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2012, 46, 644–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prince, E.J.; Siegel, D.J.; Carroll, C.P.; Sher, K.J.; Bienvenu, O.J. A Longitudinal Study of Personality Traits, Anxiety, and Depressive Disorders in Young Adults. Anxiety Stress Coping 2021, 34, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S.C.; Levinson, C.A.; Rodebaugh, T.L.; Menatti, A.; Weeks, J.W. Social Anxiety and the Big Five Personality Traits: The Interactive Relationship of Trust and Openness. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2015, 44, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, K.A.; Elliott, R.; Ware, K.; Juhasz, G.; Brown, L.J.E. Associations Between Facets and Aspects of Big Five Personality and Affective Disorders: A Systematic Review and Best Evidence Synthesis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 288, 175–188. [Google Scholar]

- Festa, C.C.; Ginsburg, G.S. Parental and Peer Predictors of Social Anxiety in Youth. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2011, 42, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, J.; Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J. Parent Relationships and Adolescents’ Depression and Social Anxiety: Indirect Associations Via Emotional Sensitivity to Rejection Threat. Aust. J. Psychol. 2014, 66, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, M.S.; Bowlby, J. An Ethological Approach to Personality Development. Am. Psychologist. 1991, 46, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Buman Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge. Master’s Thesis, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, C.M.; Maccoby, E.E.; Dornbusch, S.M. Caught Between Parents: Adolescents’ Experience in Divorced Homes. Child Dev. 1991, 62, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, Q.; Deng, L.; Fang, X.; Liu, Z.; Lan, J. Parent-Child Relationship and Internet Addiction among Adolescents: The Mediating Role of Loneliness. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2011, 27, 641–647. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L. Does Class Size Affect Students’ Non-Cognitive Abilities?—An Empirical Study Based on CEPS. Educ. Econ. 2020, 1, 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, C.R.; Harris, C.; Anderson, J.R.; Holleran, S.A.; Irving, L.M.; Sigmon, S.T.; Harney, P. The Will and The Ways: Development and Validation of an Individual-differences Measure of Hope. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 60, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Sun, Y. The Examination of the Reliability and Validity of the Chinese Version of the Children’s Hope Scale. Chin. J. Ment. Health 2011, 6, 454–459. [Google Scholar]

- LaGreca, A.M.; Ingles, C.J.; Lai, B.S.; Marzo, J.C. Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents: Factorial Invariance Across Gender and Age in Hispanic American Adolescents. Assessment 2015, 22, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Su, L.; Jin, Y. Norms of the Children’s Social Anxiety Scale in Chinese urban areas. Chin. J. Child Health 2006, 14, 335–337. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob, C. A Power Primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar]

- Kumpfer, K.L.; Summerhays, J.F. Prevention Approaches to Enhance Resilience Among High-Risk Youth: Comments on the Papers of Dishion & Connell and Greenberg. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1094, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McElwain, A.D.; Bub, K.L. Changes in Parent–child Relationship Quality Across Early Adolescence: Implications for Engagement in Sexual Behavior. Youth Soc. 2018, 50, 204–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oriol, X.; Miranda, R.; Oyanedel, J.C.; Torres, J. The Role of Self-control and Grit in Domains of School Success in Students of Primary and Secondary School. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starrels, M.E. Gender Differences in Parent-child Relations. J. Fam. Issues. 1994, 15, 148–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, B.F. The Relationship Between Creativity and Self-Directed Learning among Adult Community College Students. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dollinger, S.J.; Dollinger, S.M.C.; Centeno, L. Identity and Creativity. Identity 2005, 5, 315–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaven, P.; Ciarrochi, J. Parental Styles, Gender and the Development of Hope and Self-esteem. Eur. J. Pers. 2008, 22, 707–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asher, M.; Asnaani, A.; Aderka, I.M. Gender Differences in Social Anxiety Disorder: A Review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 56, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Osso, L.; Abelli, M.; Pini, S.; Carpita, B.; Carlini, M.; Mengali, F.; Massimetti, G. The Influence of Gender on Social Anxiety Spectrum Symptoms in a Sample of University Students. Riv. Psichiatr. 2015, 50, 295–301. [Google Scholar]

- Izzaty, R.E.; Ayriza, Y. Parental Bonding as a Predictor of Hope in Adolescents. Psikohumaniora 2021, 6, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowska, D.M.; Gralewski, J. The Familial Context of Children’s Creativity: Parenting Styles and the Climate for Creativity in Parent–child Relationship. Creat. Stud. 2022, 15, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yendork, J.S. Vulnerabilities in Ghanaian Orphans: Using the Ecological Systems Theory as a Lens. New Ideas Psychol. 2020, 59, 100811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, M.E. The Role of the Father in Child Development, 5th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kuppens, S.; Grietens, H.; Onghena, P.; Michiels, D. Associations Between Parental Control and Children’s Overt and Relational Aggression. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2009, 33, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snyder, C.R.; Shorey, H.S.; Cheavens, J.; Pulvers, K.M.; Adams, V.H.; Wiklund, C. Hope and Academic Success in College. J. Educ. Psychol. 2002, 94, 820–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, A.L.; Peterson, C.; Matthews, M.D.; Kelly, D.R. Grit: Perseverance and Passion for Long-term Goals. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1087–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashdan, T.B.; Steger, M.F. Expanding the Topography of Social Anxiety: An Experience-sampling Assessment of Positive Emotions, Positive Events, and Emotion Suppression. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 17, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, N.B.; Richey, J.A.; Cromer, K.R.; Buckner, J.D. Dispositional anxiety and negative reinforcement sensitivity. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2006, 40, 483–494. [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel, K.R.; Barry, C.M.; Caldwell, K.A. Friendships in Middle School: Influences on Motivation and School Adjustment. J. Educ. Psychol. 2011, 96, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry-Smith, J.E.; Mannucci, P.V. From Creativity to Innovation: The Social Network Drivers of the Four Phases of the Idea Journey. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2017, 42, 53–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runco, M.A.; Charles, R.J. Judgments of Originality and Appropriateness as Predictors of Creativity. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1993, 15, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bögels, S.M.; Brechman-Toussaint, M.L. Family Issues in Child Anxiety: Attachment, Family Functioning, Parental Rearing, and Beliefs. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 26, 834–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredricks, J.A.; Blumenfeld, P.C.; Paris, A.H. School Engagement: Potential of the Concept, State of the Evidence. Rev. Educ. Res. 2004, 74, 59–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Ju, J.; Liang, L.; Bian, Y. Trajectories of Chinese Paternal Emotion-related Socialization Behaviors During Early Adolescence: Contributions of Father and Adolescent Factors. Fam. Process. 2023, 63, e12913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China (MEPRC). The Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Promotion of Family Education. 2021. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_sjzl/sjzl_zcfg/zcfg_qtxgfl/202110/t20211025_574749.html (accessed on 17 February 2023).

- Hofer, S.M.; Sliwinski, M.J.; Flaherty, B.P. Understanding Ageing: Further Commentary on the Limitations of Cross-sectional Designs for Ageing Research. Gerontology 2002, 48, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 FCR | 1 | ||||||||

| 2 MCR | 0.66 ** | 1 | |||||||

| 3 Grit | 0.17 ** | 0.17 ** | 1 | ||||||

| 4 INO | 0.20 ** | 0.16 ** | 0.52 ** | 1 | |||||

| 5 COS | 0.26 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.65 ** | 0.60 ** | 1 | ||||

| 6 Hope | 0.28 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.39 ** | 0.50 ** | 0.45 ** | 1 | |||

| 7 SA | −0.30 ** | −0.21 ** | −0.07 * | −0.18 ** | −0.13 ** | −0.24 ** | 1 | ||

| 8 NPF | 0.11 ** | 0.11 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.14 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.26 ** | −0.10 ** | 1 | |

| 9 NNF | −0.06 | −0.15 ** | −0.10 ** | 0.08 * | −0.09 * | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 1 |

| Total Mean | 3.64 ± 0.92 | 3.75 ± 0.79 | 3.27 ± 0.61 | 3.11 ± 0.60 | 3.10 ± 0.56 | 4.20 ± 1.19 | 0.76 ± 0.47 | 2.66 ± 0.43 | 1.54 ± 0.53 |

| Female | 3.55 ± 0.88 | 3.72 ± 0.78 | 3.27 ± 0.58 | 3.03 ± 0.54 | 3.12 ± 0.50 | 4.11 ± 1.11 | 0.86 ± 0.45 | 2.69 ± 0.39 | 1.35 ± 0.42 |

| Male | 3.73 ± 0.95 | 3.78 ± 0.80 | 3.27 ± 0.65 | 3.18 ± 0.64 | 3.08 ± 0.61 | 4.30 ± 1.26 | 0.66 ± 0.46 | 2.64 ± 0.47 | 1.74 ± 0.56 |

| Primary school | 3.85 ± 0.91 | 3.90 ± 0.73 | 3.34 ± 0.54 | 3.23 ± 0.56 | 3.21 ± 0.50 | 4.26 ± 1.12 | 0.74 ± 0.48 | 2.60 ± 0.43 | 1.58 ± 0.48 |

| Secondary school | 3.52 ± 0.91 | 3.67 ± 0.81 | 3.23 ± 0.65 | 3.04 ± 0.61 | 3.04 ± 0.58 | 4.17 ± 1.23 | 0.78 ± 0.46 | 2.70 ± 0.43 | 1.52 ± 0.55 |

| Min | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Max | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Alpha | 0.89 | 0.85 | 0.76 | 0.69 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.77 | 0.78 |

| Model 1 (SE) | Model 2 [95%CI] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grit | INO | COS | Hope | Grit | INO | COS | Hope | |

| Gender | −0.026 (0.026) | 0.143 *** (0.025) | −0.078 ** (0.024) | 0.091 *** (0.023) | 0.029 [−0.028–0.085] | 0.087 ** [0.028–0.141] | −0.028 [−0.081–0.024] | 0.044 [−0.005–0.093] |

| Grade | 0.129 *** (0.025) | 0.164 *** (0.024) | 0.197 *** (0.023) | 0.092 *** (0.023) | 0.139 *** [0.087–0.189] | 0.150 *** [0.099–0.200] | 0.188 *** [0.142–0.234] | 0.055 * [0.009–0.100] |

| FCR | 0.099 ** (0.032) | 0.142 *** (0.033) | 0.182 *** (0.03) | 0.158 *** (0.029) | 0.101 ** [0.027–0.175] | 0.144 *** [0.068–0.223] | 0.184 *** [0.114–0.255] | 0.160 *** [0.088–0.235] |

| MCR | 0.101 ** (0.031) | 0.070 * (0.031) | 0.128 *** (0.028) | 0.183 *** (0.028) | 0.102 ** [0.030–0.173] | 0.071 [−0.004–0.147] | 0.130 *** [0.064–0.195] | 0.186 *** [0.116–0.256] |

| SA | −0.024 (0.027) | −0.134 *** (0.027) | −0.053 * (0.025) | −0.204 *** (0.023) | −0.025 [−0.087–0.038] | −0.137 *** [−0.199–0.074] | −0.054 [−0.113–0.004] | −0.209 *** [−0.263–0.154] |

| NPF | 0.287 *** (0.029) | 0.224 *** (0.03) | 0.275 *** (0.028) | 0.222 *** (0.027) | 0.289 *** [0.225–0.353] | 0.226 *** [0.155–0.295]) | 0.277 *** [0.214–0.339] | 0.224 *** [0.163–0.284] |

| NNF | −0.137 *** (0.029) | 0.054 (0.029) | −0.155 *** (0.027) | −0.005 (0.025) | −0.150 *** [−0.220–0.082] | 0.059 [−0.012–0.131] | −0.169 *** [−0.234–0.104] | −0.006 [−0.067–0.055] |

| FCR-SA-NCSs | - | - | 0.026 [0.013–0.043] | 0.010 [−0.001–0.023] | 0.040 [0.024–0.060] | |||

| MCR-SA-NCSs | - | - | 0.012 [0.002–0.025] | 0.005 [0.000–0.013] | 0.019 [0.004–0.035] | |||

| FCR-NPF-NCSs | - | 0.046 [0.022–0.070] | 0.036 [0.017–0.056] | 0.044 [0.022–0.067] | 0.035 [0.017–0.056] | |||

| MCR-NPF-NCSs | - | 0.024 [0.001–0.048] | 0.019 [0.001–0.038] | 0.023 [0.001–0.046] | 0.019 [0.001–0.038] | |||

| FCR-NNF-NCSs | - | 0.016 [0.005–0.029] | - | 0.018 [0.005–0.032] | - | |||

| MCR-NNF-NCSs | - | 0.022 [0.009–0.038] | - | 0.025 [0.012–0.041] | - | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kuang, X.; Ren, F.; Lee, J.C.-K.; Li, H. Parent–Child Relationships and Adolescents’ Non-Cognitive Skills: Role of Social Anxiety and Number of Friends. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 961. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100961

Kuang X, Ren F, Lee JC-K, Li H. Parent–Child Relationships and Adolescents’ Non-Cognitive Skills: Role of Social Anxiety and Number of Friends. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(10):961. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100961

Chicago/Turabian StyleKuang, Xiaoxue, Fen Ren, John Chi-Kin Lee, and Hui Li. 2024. "Parent–Child Relationships and Adolescents’ Non-Cognitive Skills: Role of Social Anxiety and Number of Friends" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 10: 961. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100961

APA StyleKuang, X., Ren, F., Lee, J. C.-K., & Li, H. (2024). Parent–Child Relationships and Adolescents’ Non-Cognitive Skills: Role of Social Anxiety and Number of Friends. Behavioral Sciences, 14(10), 961. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100961