“SHIELDing” Our Educators: Comprehensive Coping Strategies for Teacher Occupational Well-Being

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Participant Recruitment and Sampling

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Approval

3. Results

3.1. Personal Well-Being Enabling Initiatives

“So, I think I’ve learned to set my boundaries. Now I’m older and better at saying, this is what I can do and take it or leave it sort of thing in a nice way. But I think leadership in every school I’ve worked at they’ve always tried to take more and push more for more. …So, I think it’s important to create boundaries and to say what you want to do and what you physically can’t do…”(Zelon)

“I think for the most part I would say to myself, I can only do what I can do within the plan that I’ve got and I’m not going to be sitting here till 11 o’clock at night marking papers and doing whatever if I don’t get it done within a certain time, it just doesn’t get done. So, I just figured, if I don’t do this, or this or this, it’s not gonna matter so much… and that was just a survival thing because, I’ve got one friend who is a person who can’t leave those things…, and she had to take time away from teaching a couple of times…. She just wearied herself to the bone, and I’m not the type of person that will do that. I will just let you know that’s enough. And I’ll do what I think is important, regardless of what anyone else is telling me is important. I’ll just make up my own mind and decide if I can do that, or if I can’t, and if I can’t, I just leave it”(Lally)

“Coping is sometimes saying ‘no’ to certain things. You know, being able to stop, but also standing your ground also to certain things …, like emails from parents. And I’ll say right now I don’t respond to emails at all. So that parents know that I also have a life outside of school. …, I’m going to respond in the morning and all that. …, I really disciplined myself to respond like during school time. So that it doesn’t become a habit for parents to just think they can just email me any time. Really discipline myself to just stop, and enjoy something else.…”(Saks)

“I exercise 3 to 4 times a week, and yeah. Eat well, try to just eat well and exercise, and going outside when I can. Take a walk. Enjoying nature and stuff that still helps me with my well-being. Going to the seaside. and that sort of stuff”(Mira)

“Every five weeks I’m taking a mental health day, and I’m going away for the weekend. And that’s a big improvement than what I’ve done previously. I’m taking some time out in the holidays to go away and look at the ocean”(Ash)

“Going for a walk, Pilates’, talking to colleagues, talking to friends…. I suppose smiling when you meet someone and genuinely interested. Finding something that is common ground. I suppose just going and talking to them”(Maz)

“So, getting out, camping and spending time with friends. Like everyone, kind of worked hard. But then they are really fun”(Sey)

“I suppose getting a good network of friends. Make time for doing things in the evening. So, I catch up with friends in the evening sometimes. I do pilates with a friend once a week so I have to go with her, and I catch up with a friend regularly to walk her dog or dogs”(Maz)

“I make time in the evenings or weekends to do something with my friends. It helps me relax and enjoy time away from school.”(Mira)

“I’m getting better at not internalising it. Like I used to think, particularly in the time when I wasn’t coping and ended up going on workers comp. I thought I should be able to deal with it myself. And I was keeping it to myself, then. So, it was just becoming big. I see a psychologist now. But I’ve only seen her twice in the last 12 months, because I did have a period where I was seeing her regularly recently in the last two years”(Ash)

“I just take a deep breath, and I just pray to God. Am a Christian, I just pray to God to help me. That’s what I do to be honest. I go to the gym to exercise, so that helps me too mentally”(Zem)

“It was that, when you leave school for the day, walk out the gate knowing that you did everything you could. You worked as hard as you could, and then you leave it there. You don’t take it home with you. So, if I have had a bad day, or the class I’m teaching is challenging, then I don’t take that home with me and think about it all night at home. I put it down there at work and then I tackle the next challenge the next day when I come. I think it’s important to have that work/life balance. let everything that has happened to remain in school so you don’t go home with them”(Raba)

“I try to relax on the weekends. I’m doing gardening, and I have a pool which is really nice so I’m lucky. We go down to the beach and go swimming. So, you know, with my children, and I’ve got 2 at home, and 2 stepchildren as well, that are here at weekends. So, you know, we take them off to the beach, and things”(Esan)

“Only because I work point 8. If I was full time, I wouldn’t have been able to do it. Point 8 is 4 days a week. One day off. Oh, on that one day I would do my school work. May be 4 or 6 h of school work. So, that I can spend my weekends more free with my family but also when it gets to Sunday evening I am also doing school work”(Maz)

3.2. School-Based Well-Being Enabling Initiatives

“I make sure I’m very open with my supervisors. So, if I’ve got things going on in my home world, I try and let them know what is going on. So, they will be more empathetic to my situation. If something was to happen or that kind of thing”(Raba)

“I trust and I know that my assistant principal and my principal are very aware of my personal well-being needs. And I get the support that I need to deal with those”(Ash)

“I think I felt more valued then, I felt more supported. I think the principal that I had then was the type of person that is always, if a parent complained about something, she’d pass it on to you if she didn’t think it was warranted. Whereas the principal that I have [now]…, they’re more likely to listen to what the parent had to say and make you more accountable to the parent, follow-up phone calls, those sorts of things all the time you know. That principal I had first had a psychology degree, was able to make staff feel valued and part of the school community, and she would protect you”(Lally)

“Talking with colleagues after school, you have a really hard day you go to the staff room and you debrief with your colleagues. They usually know what I’m talking about”(Sod)

“I think it is also important to get into the staffroom and interact with other people. It kind of even limits any stress or kind of just brings you back into perspective. So that you don’t get stuck in your classroom doing everything you need to do. Sometimes it’s important to prioritise just being social, interacting with other people so that’s helpful. And then as well I got given some advice when I started my teaching career”(Raba)

“I have respect for my colleagues, and I know that they have respect for me. They have a lot of respect for me and my role. We have bond together… which is important. You can be yourself. Yeah, everybody can be (themselves)…I would say that 90% of the staff feel like they can be themselves and not be judged”(Ash)

“Talking to colleagues actually, and especially because I was, quite new to teaching, and I had a really good sort of bunch of colleagues around me, and I could talk to them about any problems at work, and they would support me”(Esan)

“If genuinely teachers are expected to do things over and above the classroom role like paperwork, for example reports, personalised plans, stuff like that, they’re generally given time out of class to work on those”(Ash)

“Because I am a part time teacher. I can maintain my stress okay. I feel like it’s in hand because I have lot of interest outside of school with animals or community, volunteering, whatever, and I have flexibility in my role. I feel a balance, and I feel happy with that. So, I can maintain any of the stress build-up from school. I can let it go. I can release it. I’m feeling good about my well-being right now”(Nath)

“I like distance [online] education because it allows for a lot more flexibility. I’m just happy with where we are at the moment.”(Penny)

“As far as the school providing me with the resources I need to work with the kids, I don’t think it’s a realistic expectation. Schools would probably need double the funding they have now to do that”(Ash)

“If I make a resource, I keep it. I don’t throw it out. I laminate it and I keep it, so it’s always there. But you’re always creating new resources too. I’ve got a lot of stuff online that I’ve made over the years and then I can go back and reuse it or I can tweak it. I try to work smarter not harder”(Ash)

“It’s not necessarily about the training it could be the physical environment, and it could be about the support that teachers need in order to be able to cater for the different needs. We know what the needs are. We understand what they are. We got that training…. We’ve got all tht. We just don’t have the means to actually carry out a program that would support the situation”(Lally)

“We tried things like proactive breaks, where the student knows, they are going to have a break at a set time, he calls it the ‘Fun House’, so it’s where he goes and they set up the punching bag, different activities. So, we’re not waiting for a meltdown to happen, then [before] taking him out for break, No!”(Saks)

“Getting to know the kids through the parents. Having meetings around what their strengths are…, manipulating the curriculum a little bit to be able to accommodate those strengths. Working around the things that might be preventing them from learning.… So really just individualised, tailored, targeted instruction”(Wet)

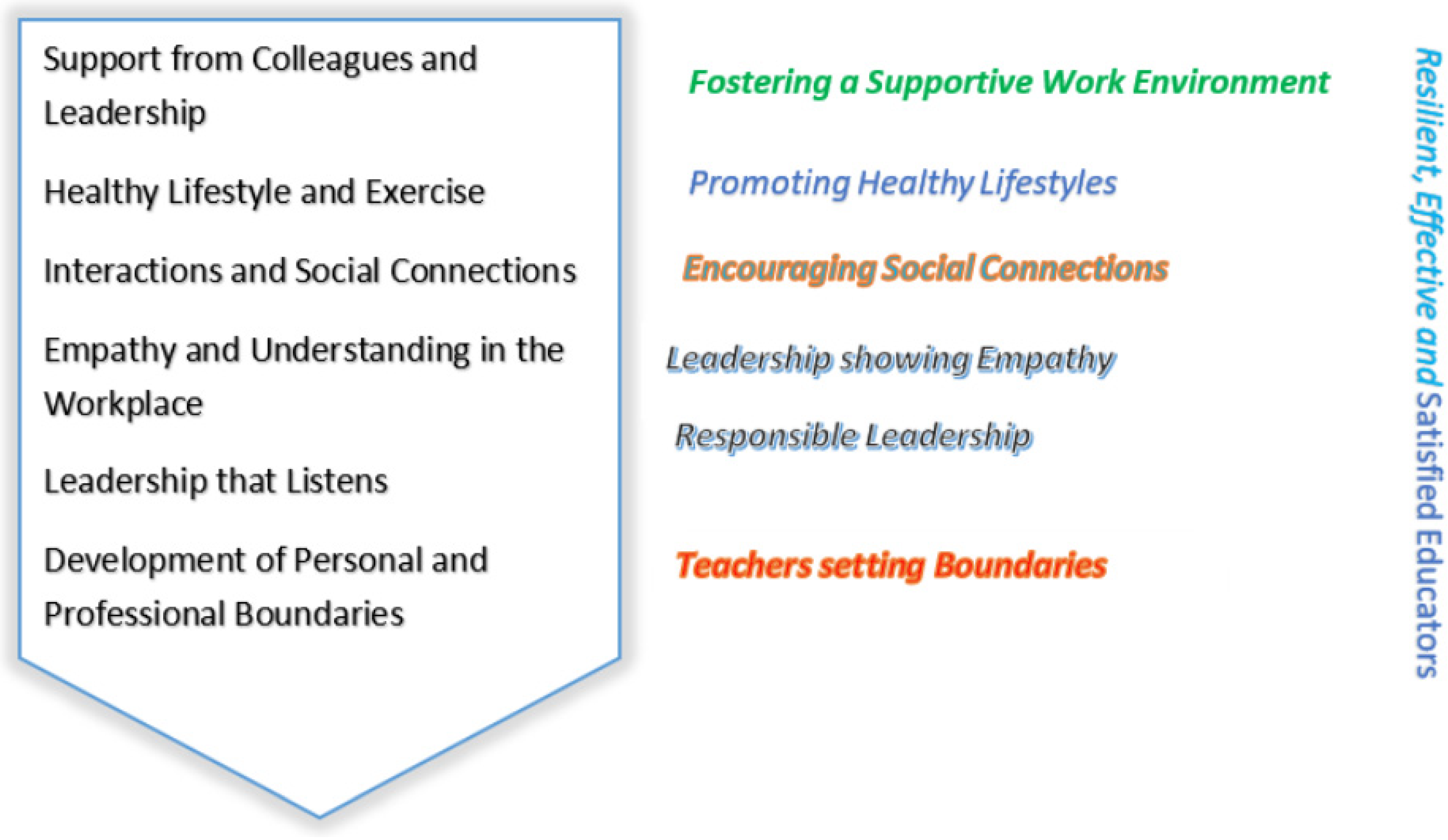

3.3. The SHIELD Model to Enhance Teachers’ Occupational Well-Being

- Support from Colleagues: The foundation of the SHIELD model is robust support from both colleagues and leadership. In a teaching environment, mutual support and collaboration among colleagues create a sense of community and shared responsibility. Teachers benefit from having colleagues who understand their challenges and provide emotional and practical support. This fosters an inclusive and supportive school culture. Ash emphasised, “The people I work with, they’re really good. They are supportive, everybody works together, it’s a collective responsibility for the children”.

- Healthy Lifestyle and Exercise: Maintaining a healthy lifestyle is vital for managing stress and enhancing overall well-being. Regular exercise, a balanced diet, and sufficient rest contribute to physical and mental health, enabling teachers to cope better with the demands of their profession. Encouraging teachers to prioritise their health can improve energy levels, reduced stress, and greater resilience. Mira shared, “I exercise 3 to 4 times a week, and eat well, try to just eat well and exercise, and going outside when I can”.

- Interactions and Social Connections: Social interactions and connections within and outside the school environment are essential for alleviating stress and maintaining a positive outlook. Engaging with colleagues and friends, participating in social activities, and building strong relationships can provide emotional support and a sense of belonging. These interactions help teachers to debrief, share experiences, and gain new perspectives on handling challenges. Raba noted, “It is important to get into the staffroom and interact with other people. It kind of even limits any stress or kind of just brings you back into perspective”.

- Empathy and Understanding in the Workplace: Empathy and understanding from both colleagues and leadership are critical components of the SHIELD model. When teachers feel understood and supported, they are more likely to express their concerns and seek help when needed. Empathy in the workplace fosters a culture of care and respect, which can significantly reduce feelings of isolation and stress. Sore mentioned, “They (leadership) have that bond, everybody does. They are pretty good in terms of support for our mental health”.

- Leadership that Listens: Effective leadership that listens and responds to teachers’ needs is fundamental for a supportive work environment. Leaders who are approachable, empathetic, and proactive in addressing teacher concerns can significantly enhance teacher morale and job satisfaction. Providing opportunities for professional development, recognising achievements, and involving teachers in decision-making processes are ways leaders can demonstrate their commitment to teacher well-being. Open communication channels between teachers and school leaders ensure that teachers feel heard, valued, and supported in their professional journey. Penny stated, “I’ve had really good support and understanding from them [leadership]. Goes both ways as well. Being honest and upfront”.

- Development of Personal and Professional Boundaries: Setting and maintaining personal and professional boundaries is crucial for preventing burnout and ensuring sustainable well-being. Teachers need to learn how to manage their workload effectively, prioritise tasks, and say no when necessary. Encouraging teachers to establish clear boundaries helps them balance their work and personal lives, reducing the risk of stress and exhaustion. Zelon said, “I think I’ve learned to set my boundaries. Now I’m older and better at saying, this is what I can do, and take it or leave it sort of thing in a nice way”.

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Practice

4.2. Strengths and Limitations of This Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- With regards to organisational support, tell me how well the school supports you?

- Describe how you manage/cope with stress at work?

- How would you describe your relationships with leadership/management?

- How would you describe your dealings/relationships with colleagues?

- To what extent do you feel supported by your other colleagues and school administrators (other school stakeholders)?

- What are the formal structures and systems in place that provide you helpful support when needed?

References

- Thakur, M.; Chandrasekaran, V.; Guddattu, V. Role Conflict and Psychological Well-Being in School Teachers: A Cross-Sectional Study from Southern India. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2018, 12, VC01–VC6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The Job Demands-Resources Model of Burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. TALIS 2013 Results: An International Perspective on Teaching and Learning; TALIS; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallum, F.; Price, D.; Graham, A.; Morrison, A. Teacher Wellbeing: A Review of the Literature; AIS: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2017; Available online: https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2017-10/apo-nid201816.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Rajesh, C.; Ashok, L.; Rao, C.R.; Kamath, V.G.; Kamath, A.; Sekaran, V.C.; Devaramane, V.; Swamy, V.T. Psychological well-being and coping strategies among secondary school teachers: A cross-sectional study. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2022, 11, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, S.V.; von der Embse, N.P.; Pendergast, L.L.; Saeki, E.; Segool, N.; Schwing, S. Leaving the teaching profession: The role of teacher stress and educational accountability policies on turnover intent. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 66, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermejo-Toro, L.; Prieto-Ursúa, M.; Hernández, V. Towards a model of teacher well-being: Personal and job resources involved in teacher burnout and engagement. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 36, 481–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, C.; O’Malley, K.; Eveleigh, F. Australian Teachers and the Learning Environment: An Analysis of Teacher Response to TALIS 2013 Final Report. 2014. Available online: https://research.acer.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1001&context=talis (accessed on 5 April 2021).

- Carroll, A.; Forrest, K.; Sanders-O’Connor, E.; Flynn, L.; Bower, J.M.; Fynes-Clinton, S.; York, A.; Ziaei, M. Teacher stress and burnout in Australia: Examining the role of intrapersonal and environmental factors. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2022, 25, 441–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, K.C.; Prewett, S.L.; Eddy, C.L.; Savala, A.; Reinke, W.M. Profiles of middle school teacher stress and coping: Concurrent and prospective correlates. J. Sch. Psychol. 2020, 78, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albulescu, P.; Tuşer, A.; Sulea, C. Effective strategies for coping with burnout. A study on romanian teachers. Psihol. Resur. Um. 2018, 16, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E.; Skaalvik, S. Teacher Stress and Coping Strategies—The Struggle to Stay in Control. Creat. Educ. 2021, 12, 1273–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, A.S.; Ploumpi, A.; Ntalla, M. Occupational stress and professional burnout in teachers of primary and secondary education: The role of coping strategies. Psychology 2013, 4, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, M.G.; Riding, R.J. Occupational stress and satisfaction in teaching. Br. Educ. Res. J. 1991, 17, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkinos, C.M. Job stressors, personality and burnout in primary school teachers. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2007, 77, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viac, C.; Fraser, P. Teachers’ well-being: A framework for data collection and analysis. In OECD Education Working Papers; Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD): Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, J.; Wilson, E. Comparing sources of stress for state and private school teachers in England. Improv. Sch. 2022, 25, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.W.; Romer, N.; Horner, R.H. Teacher Well-Being and the Implementation of School-Wide Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports. J. Posit. Behav. Interv. 2012, 14, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perryman, J.; Calvert, G. What motivates people to teach, and why do they leave? Accountability, performativity and teacher retention. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 2019, 68, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allies, S. Supporting Teacher Wellbeing: A Practical Guide for Primary Teachers and School Leaders; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borman, G.D.; Dowling, N.M. Teacher Attrition and Retention: A Meta-Analytic and Narrative Review of the Research. Rev. Educ. Res. 2008, 78, 367–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E.M.; Skaalvik, S. Job demands and job resources as predictors of teacher motivation and well-being. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2018, 21, 1251–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forlin, C. Inclusion: Identifying potential stressors for regular class teachers. Educ. Res. 2001, 43, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Bakker, A.B.; Schaufeli, W.B. Burnout and work engagement among teachers. J. Sch. Psychol. 2006, 43, 495–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buric, I.; Sliskovic, A.; Penezic, Z. Understanding teacher well-being: A cross-lagged analysis of burnout, negative student-related emotions, psychopathological symptoms, and resilience. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 39, 1136–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenzel, A.C. Teacher emotions. In Educational Psychology Handbook Series. International Handbook of Emotions in Education; Pekrun, R., Linnenbrink-Garcia, L., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2014; pp. 494–518. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, A.H.S.; Chen, K.; Chong, E.Y.L. Work stress of teachers from primary and secondary schools in Hong Kong. In Proceedings of the International Multiconference of Engineers and Computer Scientists, Hong Kong, 17–19 March 2010; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Timms, C.; Graham, D.; Caltabiano, M. Gender implication of perceptions of trustworthiness of school administration and teacher burnout/job stress. Aus. J. Soc. Issues 2006, 41, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwoko, J.C.; Emeto, T.I.; Malau-Aduli, A.E.O.; Malau-Aduli, B.S. A systematic review of the factors that influence teachers’ occupational well-being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhuri, S.; Muhonen, H.; Pakarinen, E.; Lerkkanen, M.-K. Teachers’ Focus of Attention in First-grade Classrooms: Exploring Teachers Experiencing Less and More Stress Using Mobile Eye-tracking. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2021, 66, 1076–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidek, Z.; Surat, S.; Kutty, F.M. Student misbehaviour in classrooms at secondary schools and the relationship with teacher job well-being. Int. J. Psychosoc. Rehabil. 2020, 24, 5373–5380. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, H.L.; Fox, H.B. Understanding Teacher Well-Being During the Covid-19 Pandemic Over Time: A Qualitative Longitudinal Study. J. Organ. Psychol. 2021, 21, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, J.; Steptoe, A.; Cropley, M. An investigation of coping strategies associated with job stress in teachers. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 1999, 69, 517–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.-L. An Appraisal Perspective of Teacher Burnout: Examining the Emotional Work of Teachers. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 21, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spilt, J.L.; Koomen, H.M.Y.; Thijs, J.T. Teacher Wellbeing: The Importance of Teacher—Student Relationships. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 23, 457–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajorek, Z.; Gulliford, J.; Taskila, T. Healthy Teachers, Higher Marks? Establishing a Link between Teacher Health and Wellbeing and Student Outcomes; The Work Foundation: London, UK, 2014; Available online: https://f.hubspotusercontent10.net/hubfs/7792519/healthy_teachers_higher_marks_report.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Folkman, S.; Lazarus, R.S. Ways of Coping Questionnaire Research Edition; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, P.D.; Martin, A.J. Coping and buoyancy in the workplace: Understanding their effects on teachers’ work-related well-being and engagement. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2009, 25, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancio, E.J.; Larsen, R.; Mathur, S.R.; Estes, M.B.; Johns, B.; Chang, M. Special Education Teacher Stress: Coping Strategies. Educ. Treat. Children. 2018, 41, 457–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, L.E.; Oxley, L.; Asbury, K. “My brain feels like a browser with 100 tabs open”: A longitudinal study of teachers’ mental health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 92, 299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stapleton, P.; Garby, S.; Sabot, D. Psychological distress and coping styles in teachers: A preliminary study. Aust. J. Educ. 2020, 64, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorilli, C.; Gabola, P.; Pepe, A.; Meylan, N.; Curchod-Ruedi, D.; Albanese, O.; Doudin, P.-A. The effect of teachers’ emotional intensity and social support on burnout syndrome. A comparison between Italy and Switzerland. Rev. Eur. Psychol. Appl. 2015, 65, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullrich, A.; Lambert, R.G.; McCarthy, C.J. Relationship of German Elementary Teachers’ Occupational Experience, Stress, and Coping Resources to Burnout Symptoms. Int. J. Stress. Manag. 2012, 19, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutz, P.A.; Davis, H.A. Emotions and Self-Regulation During Test Taking. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 35, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamama, L.; Ronen, T.; Shachar, K.; Rosenbaum, M. Links Between Stress, Positive and Negative Affect, and Life Satisfaction Among Teachers in Special Education Schools. J. Happiness. Stud. 2013, 14, 731–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J. Stress Coping Strategies and Status of Job Burnout of Middle School Teachers in China. In Proceedings of the 2021 5th International Seminar on Education, Management and Social Sciences (ISEMSS 2021), Chengdu, China, 9–11 July 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samfira, E.M.; Paloş, R. Teachers’ Personality, Perfectionism, and Self-Efficacy as Predictors for Coping Strategies Based on Personal Resources. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 751930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustems-Carnicer, J.; Calderon, C.; Calderon-Garrido, D.; Martin-Piñol, C. Academic Progress, Coping Strategies and Psychological Distress among Teacher Education Students. Int. J. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 9, 290–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buettner, C.K.; Jeon, L.; Hur, E.; Garcia, R.E. Teachers’ Social-Emotional Capacity: Factors Associated with Teachers’ Responsiveness and Professional Commitment. Early Educ. Dev. 2016, 27, 1018–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, S.; Johnson, B. Resilient teachers: Resisting stress and burnout. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2004, 7, 399–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. (Ed.) Five qualitative approaches to inquiry. In Qualitative Inquiry Design: Choosing among Five Approaches; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 53–84. [Google Scholar]

- Hatch, J.A. Doing Qualitative Research in Education Settings, Second Edition, 1st ed.; State University of New York Press: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative & Mixed Methods Approaches, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Fam. Health. Int. 2006, 8, 59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cresswell, J.W. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches to Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, J. Teacher Stress and Coping Strategies: A National Snapshot. Educ. Forum. 2012, 76, 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, F. (Dys)functional Cognitive-Behavioral Coping Strategies of Teachers to Cope with Stress, Anxiety, and Depression. Deviant Behav. 2022, 43, 1558–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P.; Patel, A.K.; Mishra, D. Gender differences in coping style among school teachers. Indian J. Health Wellbeing 2016, 7, 164. [Google Scholar]

- Lindqvist, H.; Weurlander, M.; Wernerson, A.; Thornberg, R. Boundaries as a coping strategy: Emotional labour and relationship maintenance in distressing teacher education situations. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2019, 42, 634–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesens, G.; Stinglhamber, F.; Luypaert, G. The impact of work engagement and workaholism on well-being: The role of work-related social support. Career Dev. Int. 2014, 19, 813–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluschkoff, K.; Elovainio, M.; Keltikangas-Järvinen, L.; Hintsanen, M.; Mullola, S.; Hintsa, T. Stressful psychosocial work environment, poor sleep, and depressive symptoms among primary school teachers. Electron. J. Res. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 14, 462–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, A. Educational change takes ages: Life, career and generational factors in teachers’ emotional responses to educational change. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2005, 21, 967–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, V.; Shah, S.; Muncer, S. Teacher stress and coping strategies used to reduce stress. Occup. Ther. Int. 2005, 12, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustems-Carnicer, J.; Calderón, C. Coping strategies and psychological well-being among teacher education students: Coping and well-being in students. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2013, 28, 1127–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquette, K.R.; Rieg, S.A. Stressors and coping strategies through the lens of Early Childhood/Special Education pre-service teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2016, 57, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darabi, M.; Macaskill, A.; Reidy, L. A qualitative study of the UK academic role: Positive features, negative aspects and associated stressors in a mainly teaching-focused university. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2017, 41, 566–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collie, R.J.; Shapka, J.D.; Perry, N.E. School Climate and Social-Emotional Learning: Predicting Teacher Stress, Job Satisfaction, and Teaching Efficacy. J. Educ. Psychol. 2012, 104, 1189–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuok, A.C.H.; Teixeira, V.; Forlin, C.; Monteiro, E.; Correia, A. The Effect of Self-Efficacy and Role Understanding on Teachers’ Emotional Exhaustion and Work Engagement in Inclusive Education in Macao (SAR). Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2020, 69, 1736–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, J.J.; Wang, C.; Watson, J.R.; Murray, L. Relationships among Principal Authentic Leadership and Teacher Trust and Engagement Levels. J. Sch. Leadersh. 2009, 19, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nobile, J. Organisational communication and its relationships with occupational stress of primary school staff in Western Australia. Aust. Educ. Res. 2016, 43, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuenzalida, Á. A Preliminary Measure of Teachers’ Occupational Well-Being in Baku Schools and Contextual Factors Affecting It. Khazar J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2021, 24, 37–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilgallon, P.; Maloney, C.; Lock, G. Early childhood teachers’ sustainment in the classroom. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2008, 33, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kennedy, Y.; Flynn, N.; O’Brien, E.; Greene, G. Exploring the impact of Incredible Years Teacher Classroom Management training on teacher psychological outcomes. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 2021, 37, 150–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.; Sharkey, J.D.; Lawrie, S.I.; Arch, D.A.N.; Nylund-Gibson, K. Elementary School Teacher Well-Being and Supportive Measures Amid COVID-19: An Exploratory Study. Sch. Psychol. 2021, 36, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skinner, B.; Leavey, G.; Rothi, D. Managerialism and teacher professional identity: Impact on well-being among teachers in the UK. Educ. Rev. 2021, 73, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, G.; Hogan, A.; Rahimi, M. Private funding in Australian public schools: A problem of equity. Aust. Educ. Res. 2019, 46, 893–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, J.; Wilson, E. Teacher wellbeing in England: Teacher responses to school-level initiatives. Camb. J. Educ. 2020, 51, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulén, A.-M.; Pakarinen, E.; Feldt, T.; Lerkkanen, M.-K. Teacher coping profiles in relation to teacher well-being: A mixed method approach. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2021, 102, 103323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nwoko, J.C.; Anderson, E.; Adegboye, O.A.; Malau-Aduli, A.E.O.; Malau-Aduli, B.S. “SHIELDing” Our Educators: Comprehensive Coping Strategies for Teacher Occupational Well-Being. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 918. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100918

Nwoko JC, Anderson E, Adegboye OA, Malau-Aduli AEO, Malau-Aduli BS. “SHIELDing” Our Educators: Comprehensive Coping Strategies for Teacher Occupational Well-Being. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(10):918. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100918

Chicago/Turabian StyleNwoko, Joy C., Emma Anderson, Oyelola A. Adegboye, Aduli E. O. Malau-Aduli, and Bunmi S. Malau-Aduli. 2024. "“SHIELDing” Our Educators: Comprehensive Coping Strategies for Teacher Occupational Well-Being" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 10: 918. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100918

APA StyleNwoko, J. C., Anderson, E., Adegboye, O. A., Malau-Aduli, A. E. O., & Malau-Aduli, B. S. (2024). “SHIELDing” Our Educators: Comprehensive Coping Strategies for Teacher Occupational Well-Being. Behavioral Sciences, 14(10), 918. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100918