Investigating Structural Relationships between Professional Identity, Learning Engagement, Academic Self-Efficacy, and University Support: Evidence from Tourism Students in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

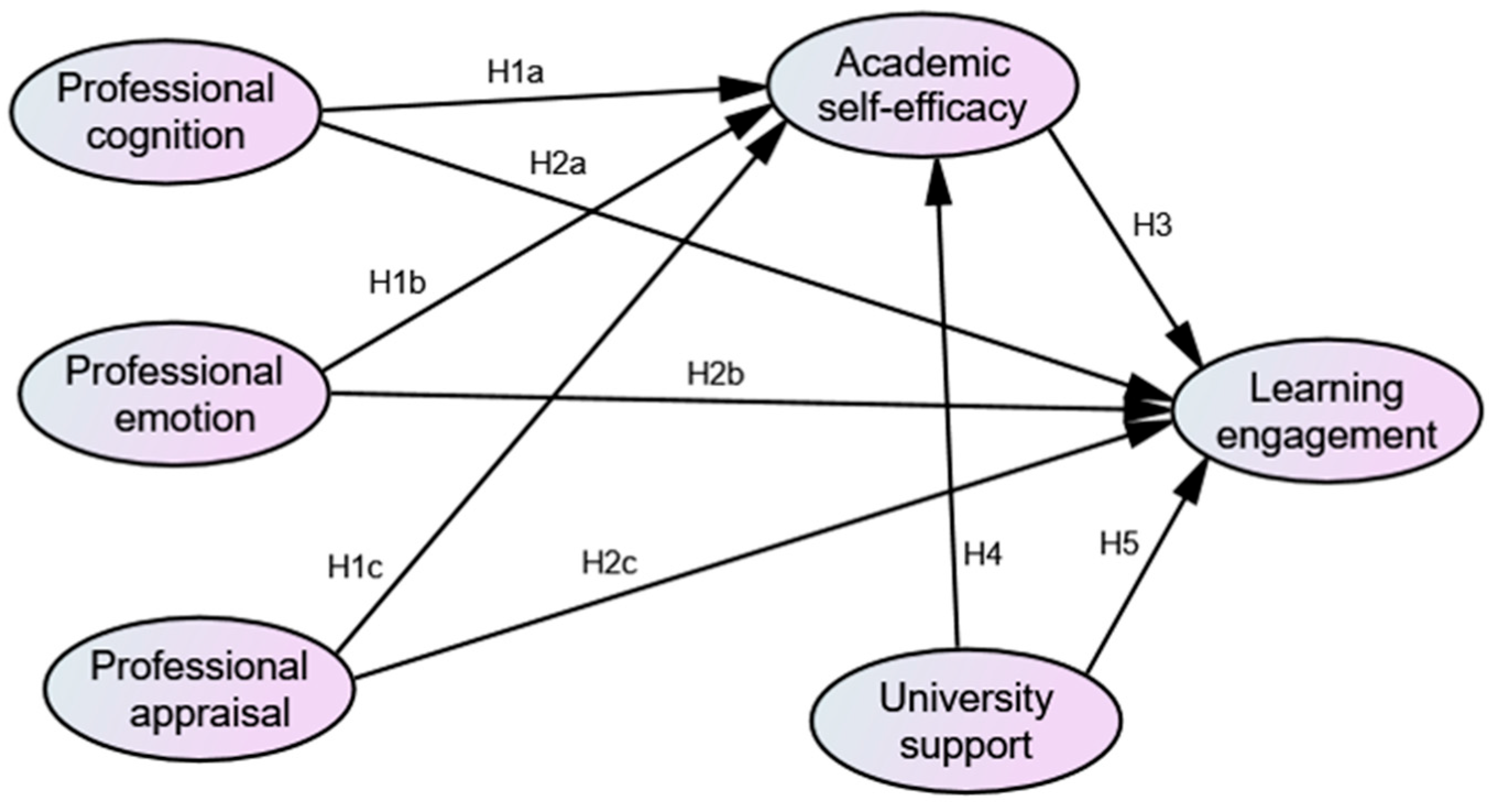

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Professional Identity

2.2. Self-Efficacy

2.3. Learning Engagement

2.4. University Support

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Survey Instrument

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Profile of Respondents

4.2. Common Method Bias

4.3. Assessment of Measurement Model

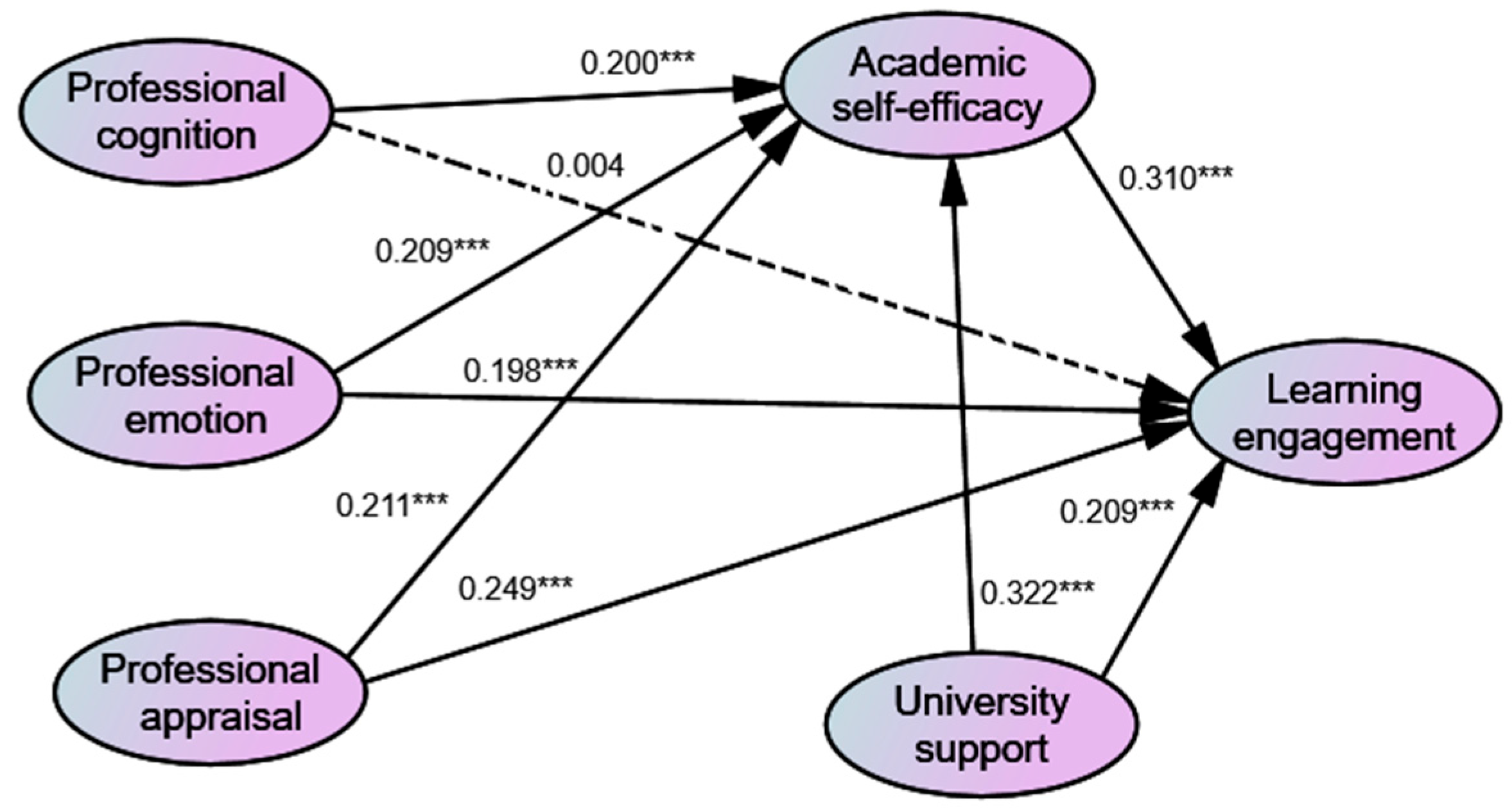

4.4. Assessment of the Structural Model

4.5. Indirect and Mediating Effects

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Further Research Suggestions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Measurement Items |

|---|---|

| Professional cognition | I know what the tourism program requires of students. |

| I understand the employment situation in the tourism program. | |

| I know what the outside world says about the tourism program. | |

| I know the position of tourism program in our university. | |

| In general, I have a clear understanding of the tourism program. | |

| Professional emotion | I am willing to engage in work related to the tourism program. |

| I have accepted the tourism program in my heart. | |

| I haven’t thought about changing my program. | |

| I have a positive evaluation of the tourism program. | |

| I have great confidence in the development prospects of the tourism program. | |

| I have developed positive feelings towards the tourism program. | |

| I am satisfied with the overall situation of the tourism program at our university. | |

| In general, I like tourism programs. | |

| Professional appraisal | I have good professional thinking in tourism. |

| My personality matches my program in tourism. | |

| The tourism program can reflect my expertise. | |

| I am persistent in my study of tourism. | |

| I am well suited to study tourism. | |

| I feel at ease studying tourism. | |

| Academic self-efficacy | I can always manage to solve difficult problems in my studies if I try hard enough. |

| If someone opposes me, I can find means and ways to get what I want in studying. | |

| It is easy for me to stick to my study aims and accomplish my academic goals. | |

| I am confident that I could deal efficiently with unexpected events during my studies. | |

| Thanks to my resourcefulness, I know how to handle unforeseen situations in study. | |

| I can solve most study problems if I invest the necessary effort. | |

| I can remain calm when facing difficulties in studying because I can rely on my coping abilities. | |

| When I am confronted with a problem in my study, I can usually find several solutions. | |

| If I am in a bind, I usually have something to do. | |

| No matter what comes my way, I’m usually able to handle it. | |

| Learning engagement | I am very resilient mentally, as far as my studies are concerned. |

| I feel strong and vigorous when I’m studying or going to class. | |

| When I’m doing my work as a student, I feel bursting with energy. | |

| I am enthusiastic about my studies. | |

| I am proud of my studies. | |

| I find my studies full of meaning and purpose. | |

| When I am studying, I forget everything else around me. | |

| I am immersed in my studies. | |

| It is difficult to detach myself from my studies. | |

| University support | My university offers professional courses on tourism. |

| My university offers project work focused on tourism. | |

| My university offers internship focused on tourism. | |

| My university offers a bachelor’s or master’s degree in tourism. | |

| My university arranges conferences/workshops on tourism. | |

| My university brings tourism students into contact with each other. | |

| My university creates awareness of tourism as a possible career choice. | |

| I feel very comfortable with the overall teaching and learning environment, atmosphere, equipment, and facilities of my university. | |

| The library of my university has abundant and authoritative information and an excellent environment, which can meet my learning needs. | |

| I can always get notice and information related to my tourism program in a timely and convenient way. | |

| The teachers/mentors at my university will take the initiative to praise and affirm my progress in my tourism studies. | |

| The teachers/mentors at my university will actively listen to my confusion in tourism studies and give me comfort. | |

| The faculty or teaching support staff of my university will give me advice and guidance for further study. |

References

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. Striding towards Higher Education Powers at the 18th Party Congress, China’s Higher Education Reform and Development of Documentary. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xwfb/xw_zt/moe_357/jjyzt_2022/2022_zt09/02gdjy/202205/t20220523_629506.html (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Song, H.S. Current Situation, Problems and Optimization Path of the Quality Assurance System of China’s Higher Education in the Popularization Stage. Contemp. Educ. Forum 2023, 2, 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, F.; Chen, Q.; Hou, B. Understanding the impacts of Chinese undergraduate tourism students’ professional identity on learning engagement. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.Y.; Zhang, H. A study on the anthems and outcome variables of professional identity of undergraduates majoring in Tourism Management—A case study of School of Tourism, Sun Yat-sen University. Tour. Forum 2022, 15, 99–112. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Wang, P.; Chen, L.Y. Reflections on the Reform of Undergraduate Practical Teaching in Tourism Management. Tour. Trib. 2006, 1, 120–123. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.H.; Xu, Y.Z.; Liao, B. Characteristics analysis and promotion strategies of Tourism Management undergraduates’ professional identity: A case study of Hengyang Normal University. For. Teach. 2023, 2, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, J.G.; Zhu, F. On the shrinking of China’s tourism undergraduate education and way out: Thoughts about thirty years of development of tourism higher education. Tour. Trib. 2008, 23, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Yang, Q. A Study on the Relationship between Professional Identity, Learning Burnout, and Learning Efficacy of Special Education Normal College Students. China Spec. Educ. 2018, 1, 39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Marchiori, D.M.; Mainardes, E.W.; Rodrigues, R.G. Do Individual Characteristics Influence the Types of Technostress Reported by Workers? Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2019, 35, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daumiller, M.; Rinas, R.; Olden, D.; Dresel, M. Academics’ motivations in professional training courses: Effects on learning engagement and learning gains. Int. J. Acad. Dev. 2021, 26, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. The investigation and analysis of tourism management students’ cognition, emotion and employment intention of professional: Taking Nanyang normal university as an example. Nanyang Norm. Univ. 2013, 12, 74–78. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, S.H.; Ashforth, B.E.; Corley, K.G. Organizational sacralization and sacrilege. Res. Organ. Behav. 2009, 29, 225–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J.S.; Roeser, R.W. Schools as developmental contexts. In Blackwell Handbook of Adolescence; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 129–148. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, M.; Bolkan, S. Intellectually stimulating students’ intrinsic motivation: The mediating influence of student engagement, self-efficacy, and student academic support. Commun. Educ. 2021, 70, 146–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azila-Gbettor, E.M.; Agbenyo, L.; Fiati, H.M.; Mensah, C. Student adjustment during COVID-19 pandemic: Exploring the moderating role of university support. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, J.K.; Fish, J.N.; Grossman, A.H.; Russell, S.T. Gay-straight alliances, inclusive policy, and school climate: LGBTQ youths’ experiences of social support and bullying. J. Res. Adolesc. 2020, 30, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Li, M.; Wang, X.; Ma, S.; Ma, J. Being bullied and depressive symptoms in Chinese high school students: The role of social support. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 284, 112676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, M. The Ethical-politics of Teacher Identity. Educ. Philos. Theory 2008, 3, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Schinoff, B.S. Identity under construction: How individuals come to define themselves in organizations. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2016, 3, 111–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markstrom-Adams, C.; Hofstra, G.; Dougher, K. The ego-virtue of fidelity: A case for the study of religion and identity formation in adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 1994, 23, 453–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salling Olesen, H. Professional identity as learning processes in life histories. J. Work. Learn. 2001, 13, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.M.; Liu, Y.C. Survey on Professional Identity of Master’s Students. Res. High. Educ. China 2007, 8, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Beagan, B.L. “Even if i don’t know what I’m doing i can make it look like i know what i’m doing”: Becoming a doctor in the 1990s. Can. Rev. Sociol. Can. Sociol. 2001, 38, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dall’Alba, G. Learning to Be Professionals; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. In The Health Psychology Reader; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A.; Freeman, W.H.; Lightsey, R. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.R.; Xin, T.; Li, Q. A study on the relationship between self-efficacy, attribution and academic achievement in Middle school students. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 1999, 4, 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Britner, S.L.; Pajares, F. Sources of science self-efficacy beliefs of middle school students. J. Res. Sci. Teach. Off. J. Natl. Assoc. Res. Sci. Teach. 2006, 43, 485–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kıran, D.; Sungur, S. Middle school students’ science self-efficacy and its sources: Examination of gender difference. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2012, 21, 619–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Liu, Y.L. Peng Wenbo. The relationship between academic Emotion and Learning Engagement of College students: The mediating role of Academic Self-efficacy. China Spec. Educ. 2020, 04, 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Pintrich, P.R.; Schunk, D.H. Motivation in Education: Theory, Research, and Applications, 2nd ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Schunk, D.H.; Mullen, C.A. Self-efficacy as an engaged learner. In Handbook of Research on Student Engagement; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 219–235. [Google Scholar]

- Tushnova, Y.; Rashchupkina, Y.; Khachaturyan, N. Features of professional identity of students “hel**” occupations with different levels of self-efficacy. SHS Web Conf. 2019, 70, 08041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhang, J.J.; Zhao, Y. The relationship between professional identity, learning engagement, and self-efficacy among college students majoring in special education: A case study of Leshan Normal University. J. Neijiang Norm. Univ. 2018, 6, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.Y.; Jiang, F. The impact of professional identity and academic self-efficacy on learning burnout among nursing students. J. Nurs. 2010, 5, 69–71. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; González-Romá, V.; Bakker, A.B. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B. UWES–Utrecht Work Engagement Scale: Test Manual; Department of Psychology, Utrecht University: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kuh, G.D.; Kinzie, J.; Cruce, T.; Shoup, R.; Gonyea, R.M. Connecting the Dots: Multi-Faceted Analyses of the Relationships between Student Engagement Results from the NSSE, and the Institutional Practices and Conditions that Foster Student Success; Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Y.G. The Development and Current Situation Investigation of a Questionnaire on Learning Engagement among College Students. J. Jimei Univ. (Educ. Sci. Ed.) 2011, 2, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Fredricks, J.A.; Blumenfeld, P.C.; Paris, A.H. School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Rev. Educ. Res. 2004, 74, 59–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, R.Q.; Yu, C. A Learning Engagement Evaluation Model for Distance Learners Based on LMS Data. Open Educ. Res. 2018, 1, 91–102. [Google Scholar]

- Su, L.Q. A Study on the Relationship between Learning Engagement and Gains of Engineering College Students. China High. Educ. Res. 2020, 2, 70–76. [Google Scholar]

- Warr, P.; Inceoglu, I. Job engagement, job satisfaction, and contrasting associations with person–job fit. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2012, 17, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Simone, S.; Planta, A.; Cicotto, G. The role of job satisfaction, work engagement, self-efficacy and agentic capacities on nurses’ turnover intention and patient satisfaction. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2018, 39, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, M.; Jackson, D. Professional identity formation in contemporary higher education students. Stud. High. Educ. 2021, 46, 885–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roseman, I.J. Cognitive determinants of emotion: A structural theory. Rev. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 5, 11–36. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, J.; Giousmpasoglou, C.; Marinakou, E. Occupational identity and culture: The case of Michelin-starred chefs. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 1362–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y. It’s not only work and pay: The moderation role of teachers’ professional identity on their job satisfaction in rural China. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2020, 15, 971–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.J. A Study on the Impact of Role Identity on Learning Engagement among College Students. J. Yichun Univ. 2017, 7, 116–120. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Sun, J.H.; Ji, F. A Study on the Relationship between Learning Engagement and Professional Identity among Medical College Students. China High. Med. Educ. 2018, 9, 39–40. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, W.Q. Research on the Current Situation of Learning Engagement among College Students; China Institute of Metrology: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Schunk, D.H. Self-efficacy and academic motivation. Educ. Psychol. 1991, 26, 207–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, C.B. Self-efficacy in the context of online learning environments: A review of the literature and directions for research. Perform. Improv. Q. 2008, 20, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferla, J.; Valcke, M.; Cai, Y. Academic self-efficacy and academic self-concept: Reconsidering structural relationships. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2009, 19, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cardona, I.; Rodriguez-Montalbán, R.; Acevedo-Soto, E.; Lugo, K.N.; Torres-Oquendo, F.; Toro-Alfonso, J. Self-efficacy and openness to experience as antecedent of study engagement: An exploratory analysis. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 46, 2163–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouweneel, E.; Le Blanc, P.M.; Schaufeli, W.B. Flourishing students: A longitudinal study on positive emotions, personal resources, and study engagement. J. Posit. Psychol. 2011, 6, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.K.; Huang, R.X.; Wu, X.L. An Empirical Study on the Relationship between Learning Engagement and Learning Self Efficacy among College Students. J. Educ. Acad. Mon. 2021, 11, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.C.; Cai, Y.Q.; Zhang, J.P. Learning efficacy: The core driving force for lifelong development. Contin. Educ. Res. 2007, 1, 129–131. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Zhang, C.H.; Jiang, X.D. A Study on the Impact of Academic Adaptation on Learning Engagement of Graduate Students Studying Abroad in China: An Analysis of Multiple Mediating Effects Based on School Belongingness and Academic Self efficacy. Jiangsu High. Educ. 2022, 4, 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.-J. Multi-dimensional explorations into the relationships between high school students’ science learning self-efficacy and engagement. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2021, 43, 1193–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, T.M.; Tsai, C.-C.; Wang, J.-C. Linking web-based learning self-efficacy and learning engagement in MOOCs: The role of online academic hardiness. Internet High. Educ. 2021, 51, 100819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Z.X.; Shi, J.H. A Study on the Mechanism of the Impact of Institutional Support on the Learning and Development of College Students: An Exploration Based on the Chinese College Student Learning and Development Tracking Survey (CCSS) Data. Res. Educ. Dev. 2020, 23, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Tinto, V. Completing College: Rethinking Institutional Action; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.H.; Fu, M.M.; Xin, Y.W.; Chen, P.P.; Sha, S. The Development of Creativity among Senior Primary School Students: Gender Differences and the Role of School Support. J. Psychol. 2020, 9, 1057–1070. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, C.H. University support, adjustment, and mental health in tertiary education students in Hong Kong. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2017, 18, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, K.R. Exploring Integration and Systems Change in a Model of Integrated Student Supports Implemented in Schools Serving Students with Complex Needs. Master’s Thesis, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Y.; Lomas, L.; MacGregor, J. Students’ perceptions of quality in higher education. Qual. Assur. Educ. 2003, 11, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyers, W.; Goossens, L. Concurrent and predictive validity of the student adaptation to college questionnaire in a sample of European freshman students. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2002, 62, 527–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doo, M.Y.; Bonk, C.J. The effects of self-efficacy, self-regulation and social presence on learning engagement in a large uni-versity class using flipped Learning. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2020, 36, 997–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, S.R.; Dodd, D.K. Student burnout as a function of personality social support, and workload. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2007, 3, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingir, S.; Tas, Y.; Gok, G.; Vural, S.S. Relationships among constructivist learning environment perceptions, motivational beliefs, self-regulation and science achievement. Res. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2013, 31, 205–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Geng, X. University students’ approaches to online learning technologies: The roles of perceived support, affect/emotion and self-efficacy in technology-enhanced learning. Comput. Educ. 2023, 194, 104695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sökmen, Y. The role of self-efficacy in the relationship between the learning environment and student engagement. Educ. Stud. 2021, 47, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattie, J.; Timperley, H. The power of feedback. Rev. Educ. Res. 2007, 77, 81–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.C.; Christensen, A.; Kackar-Cam, H.Z.; Trucano, M.; Fulmer, S.M. Enhancing students’ engagement: Report of a 3-year intervention with middle school teachers. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2014, 51, 1195–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, B.C.; Skinner, E.A.; Connell, J.P. What motivates children’s behavior and emotion? Joint effects of perceived control and autonomy in the academic domain. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 65, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeve, J. A self-determination theory perspective on student engagement. In Handbook of Research on Student Engagement; Christenson, S., Reschly, A., Wylie, C., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 149–172. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Tan, S.C.; Li, L. Technostress in university students’ technology-enhanced learning: An investigation from multi-dimensional person-environment misfit. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 105, 106208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Wang, Q.; Wu, L.; Dong, Y. Exploring the structural relationship between university support, students’ technostress, and burnout in technology-enhanced learning. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2022, 31, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, V.E.; Smith, J.B. Effects of high school restructuring and size on early gains in achievement and engagement. Sociol. Educ. 1995, 68, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voelkl, K.E. Identification with school. Am. J. Educ. 1997, 105, 294–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, A.M.; Gheen, M.H.; Midgley, C. Why do some students avoid asking for help? An examination of the interplay among students’ academic efficacy, teachers’ social–emotional role, and the classroom goal structure. J. Educ. Psychol. 1998, 90, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.-H.; Lin, H.-W.; Lin, R.-M.; Tho, P.D. Effect of peer interaction among online learning community on learning engagement and achievement. Int. J. Distance Educ. Technol. 2019, 17, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindermann, T.A. Natural peer groups as contexts for individual development: The case of children’s motivation in school. Dev. Psychol. 1993, 29, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, R.V.; Wagner, U.; Steelmaker, J. The utility of broader conceptualization of organizational identification: Which aspects really matter? J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2004, 77, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R.; Bäßler, J.; Kwiatek, P.; Schroder, K.; Zhang, J.X. The assessment of optimistic self-beliefs: Comparison of the German, Spanish, and Chinese versions of the general self-efficacy scale. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 46, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breevaart, K.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Hetland, J. The measurement of state work engagement. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2012, 28, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.-S. Computer self-efficacy, learning performance, and the mediating role of learning engagement. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 72, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, S.; Yousafzai, S.Y.; Soriano, Y.D.; Muffatto, M. The role of perceived university support in the formation of students’ entrepreneurial intention. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 51, 1127–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Pyo, J. Creative Self-Efficacy, Cognitive Reappraisal, Positive Affect, and Career Satisfaction: A Serial Mediation Model. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotz, O.; Kerstin, L.-G.; Krafft, M. Evaluation of structural equation models using the partial least squares (PLS) approach. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares: Concepts, Methods and Applications; Esposito Vinzi, V., Wynne, W.C., Henseler, J., Wang, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 691–711. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, H.; Leung, X.; Li, X.; Kwon, J. What influences Chinese students’ intentions to pursue hospitality careers? A comparison of three-year versus four-year hospitality programs. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2018, 23, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach for structural equation modelling. In Modern Methods for Business Research; Marcoulides, G.A., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modelling in international marketing. Adv. Int. Mark. 2009, 20, 277–320. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Li, S.; Zheng, J.; Guo, J. Medical students’ motivation and academic performance: The mediating roles of self-efficacy and learning engagement. Med. Educ. Online 2020, 25, 1742964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs | Items | Loading | Cronach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Professional Cognition | PC1 | 0.860 | 0.900 | 0.902 | 0.714 |

| PC2 | 0.848 | ||||

| PC3 | 0.837 | ||||

| PC4 | 0.808 | ||||

| PC5 | 0.869 | ||||

| Professional Emotion | PE1 | 0.868 | 0.924 | 0.927 | 0.654 |

| PE2 | 0.839 | ||||

| PE3 | 0.814 | ||||

| PE4 | 0.819 | ||||

| PE5 | 0.767 | ||||

| PE6 | 0.799 | ||||

| PE7 | 0.704 | ||||

| PE8 | 0.849 | ||||

| Professional Appraisal | PA1 | 0.811 | 0.921 | 0.922 | 0.718 |

| PA2 | 0.856 | ||||

| PA3 | 0.837 | ||||

| PA4 | 0.844 | ||||

| PA5 | 0.870 | ||||

| PA6 | 0.867 | ||||

| Learning engagement | LE1 | 0.735 | 0.910 | 0.914 | 0.582 |

| LE2 | 0.777 | ||||

| LE3 | 0.749 | ||||

| LE4 | 0.801 | ||||

| LE5 | 0.836 | ||||

| LE6 | 0.775 | ||||

| LE7 | 0.713 | ||||

| LE8 | 0.711 | ||||

| LE9 | 0.762 | ||||

| Academic Self-efficacy | SE1 | 0.793 | 0.942 | 0.943 | 0.656 |

| SE2 | 0.774 | ||||

| SE3 | 0.786 | ||||

| SE4 | 0.821 | ||||

| SE5 | 0.832 | ||||

| SE6 | 0.833 | ||||

| SE7 | 0.756 | ||||

| SE8 | 0.872 | ||||

| SE9 | 0.851 | ||||

| University support | SE10 | 0.778 | |||

| US1 | 0.826 | 0.962 | 0.962 | 0.686 | |

| US2 | 0.826 | ||||

| US3 | 0.826 | ||||

| US4 | 0.810 | ||||

| US5 | 0.830 | ||||

| US6 | 0.812 | ||||

| US7 | 0.816 | ||||

| US8 | 0.820 | ||||

| US9 | 0.850 | ||||

| US10 | 0.857 | ||||

| US11 | 0.822 | ||||

| US12 | 0.821 | ||||

| US13 | 0.851 |

| PA | PC | PE | LE | SE | US | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA | 0.848 | |||||

| PC | 0.783 | 0.845 | ||||

| PE | 0.871 | 0.852 | 0.809 | |||

| LE | 0.809 | 0.760 | 0.824 | 0.763 | ||

| SE | 0.774 | 0.777 | 0.807 | 0.823 | 0.810 | |

| US | 0.719 | 0.735 | 0.746 | 0.774 | 0.772 | 0.828 |

| Endogenous Latent Construct | Coefficients of Determination (R2) | Predictive Relevance (Q2) |

|---|---|---|

| Learning engagement | 0.781 | 0.445 |

| Academic self-efficacy | 0.733 | 0.476 |

| Hypothesized Relationships | Coefficient | Results |

|---|---|---|

| H1a: Professional Cognition → Academic Self-efficacy | 0.200 *** | Supported |

| H1b: Professional Emotion → Academic Self-efficacy | 0.209 *** | Supported |

| H1c: Professional Appraisal → Academic Self-efficacy | 0.211 *** | Supported |

| H2a: Professional Cognition → Learning engagement | 0.004 | Not supported |

| H2b: Professional Emotion → Learning engagement | 0.198 *** | Supported |

| H2c: Professional Appraisal → Learning engagement | 0.249 *** | Supported |

| H3: Academic Self-efficacy → Learning engagement | 0.310 *** | Supported |

| H4: University support →Academic Self-efficacy | 0.322 *** | Supported |

| H5: University support → Learning engagement | 0.209 *** | Supported |

| Original Sample (O) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics | p Values | Variance Accounted for Value (VAF) | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Professional cognition → Academic self-efficacy → Learning engagement | 0.058 | 0.022 | 2.661 | 0.008 | 93.548% | Full mediation |

| Professional emotion → Academic self-efficacy → Learning engagement | 0.079 | 0.033 | 2.402 | 0.016 | 26.246% | Partial mediation |

| Professional appraisal → Academic self-efficacy → Learning engagement | 0.054 | 0.028 | 1.950 | 0.051 | 19.148% | No mediation |

| University support → Academic self-efficacy → Learning engagement | 0.096 | 0.029 | 3.323 | 0.001 | 31.893% | Partial mediation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, F.; Hou, B. Investigating Structural Relationships between Professional Identity, Learning Engagement, Academic Self-Efficacy, and University Support: Evidence from Tourism Students in China. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010026

Chen Q, Zhang Q, Yu F, Hou B. Investigating Structural Relationships between Professional Identity, Learning Engagement, Academic Self-Efficacy, and University Support: Evidence from Tourism Students in China. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Qian, Qingchuo Zhang, Fenglong Yu, and Bing Hou. 2024. "Investigating Structural Relationships between Professional Identity, Learning Engagement, Academic Self-Efficacy, and University Support: Evidence from Tourism Students in China" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010026

APA StyleChen, Q., Zhang, Q., Yu, F., & Hou, B. (2024). Investigating Structural Relationships between Professional Identity, Learning Engagement, Academic Self-Efficacy, and University Support: Evidence from Tourism Students in China. Behavioral Sciences, 14(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010026