Whole-Body Photobiomodulation Therapy for Fibromyalgia: A Feasibility Trial

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Trial Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Interventions

2.4. Outcomes

2.5. Sample Size

2.6. Statistical Methods

3. Results

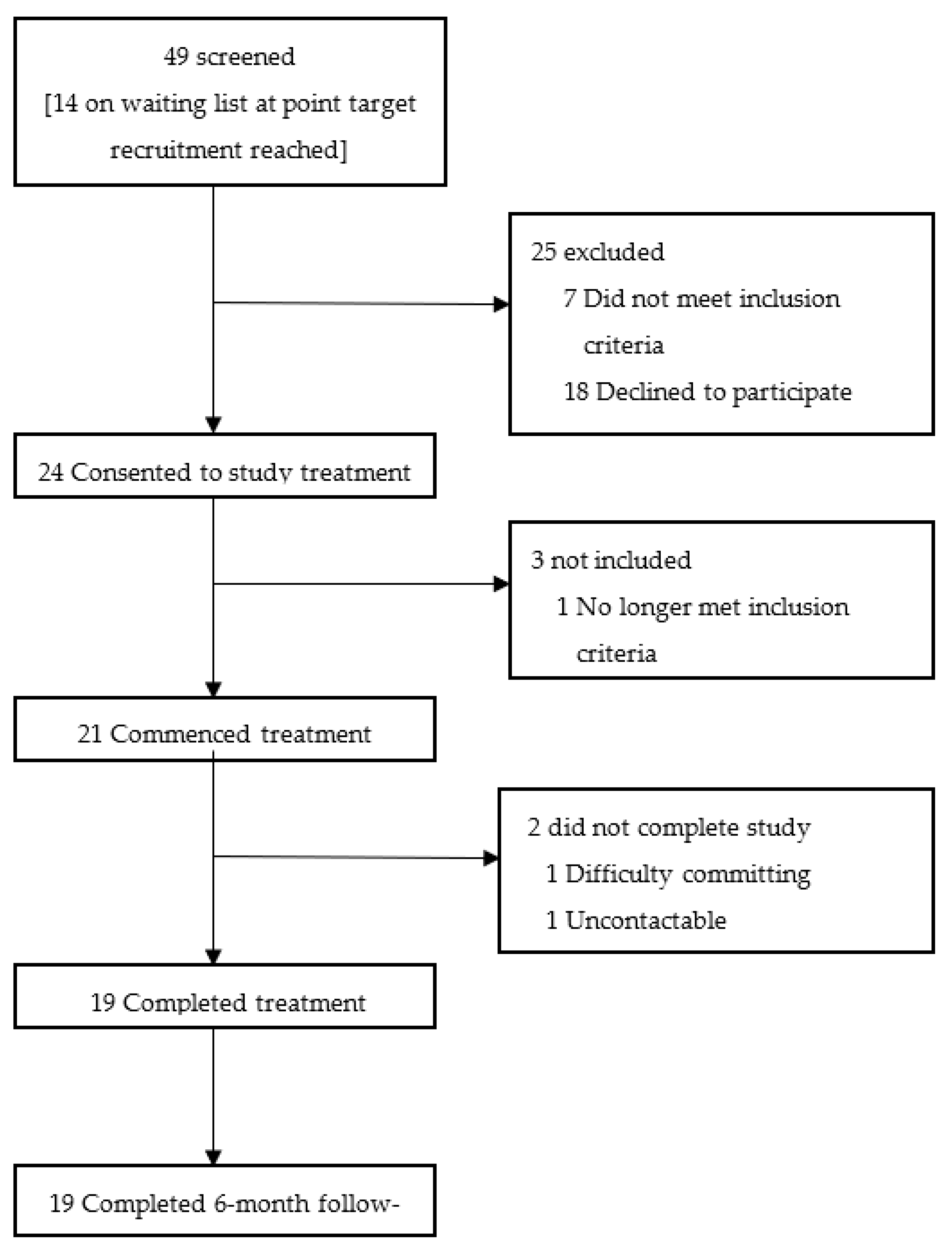

3.1. Participant Flow

3.2. Recruitment

3.3. Baseline Data

3.4. Primary (Feasibility) Outcomes

3.4.1. Recruitment-Related Feasibility Outcomes

- Eligibility: of the 25 participants that were excluded prior to consent, seven were excluded due to ineligibility; one became pregnant, two did not meet the inclusion criteria for pain type, two had received recent steroid injections and two had uncontrolled co-morbidities. Throughout the recruitment period, a considerable number of participants did not reach the screening phase due to having recently received steroids.

- Barriers to uptake: of the 18 participants that ‘declined to participate’, seven participants could not commit the time to the treatment schedule, three participants felt they would be too fatigued by the travel, one participant could not afford the petrol for the travel (lived more than 20 miles away), one participant was worried about personal unreliability due to unpredictability of flare ups, two participants were uncontactable, one participant had moved areas, one participant was actively trying to become pregnant and one participant was claustrophobic. The latter participant came to try the device but could not enter the study due to physical discomfort in the device and claustrophobia. One participant was commenced on a course of oral steroids during the latter stages of her treatment schedule in order to treat a respiratory infection.

- Trial retention: of the three participants that consented but did not proceed, one participant became pregnant, one became uncontactable and one participant re-considered due to both taxi costs and getting to top of the list for a steroid injection for their pain condition, and did not wish to postpone this. Subsequent to commencing the treatment schedule, one participant exited the trial after four ad hoc treatments due to difficulty with committing to the treatment schedule. The other participant exited the trial after completing 17 treatments secondary to a reported road traffic collision. All participants (n = 19) were contactable at a 6-month follow up.

3.4.2. Trial-Related Feasibility Outcomes

- Provision of information prior to trial: all participants were satisfied with the level of information they received prior to commencing the trial. One participant (5.3%) felt a video demonstration of the device prior to visiting the hospital might be helpful.

- Acceptability of treatment schedule: twelve participants (63.1%) were satisfied with the number and frequency of treatment sessions. One participant was ‘not sure’ and the remaining six participants (31.6%) said they would like to see a change in the number and frequency of treatment sessions. Of the latter six, five participants expressed a preference towards more frequent treatments (daily), longer treatment duration and an increased number of treatments over a longer time period. The remaining participant felt three days per week were too many visits. The same participant found the expense of transport an obstacle.

- Adherence to treatment schedule: for those participants who received the full treatment schedule, and the one participant receiving the majority of treatments, 50% participants (n = 10) received three treatments thrice weekly (Monday, Wednesday, Friday) for six weeks, as scheduled. Ten participants were non-adherent with the treatment schedule. These participants received all 18 treatments spanning a duration of 7–9 weeks, over which time 41 visits were postponed. Twenty-five visits (61%) were missed on the scheduled day attributable to medical reasons; ‘fibro flare’ (n = 2), fall (n = 1), poor sleep (n = 2), viral symptoms (n = 5), COVID-19 (n = 7), migraine (n = 1), burning sensations behind cheekbones (n = 4) and elective sinus surgery (n = 3). Practical reasons included lost car keys (n = 1), staffing and investigator availability (n = 3), dissatisfaction with travel expenses (n = 4), ‘Did Not Attend’ (n = 4) and ‘unforeseen circumstances’ (n = 1). Family reasons included a daughter having surgery (n = 1) and bereavement (n = 1). Work/study reasons included attending a course in Wales (n = 1).

- Acceptability of travel and expenses: single journey distance ranged from 0.6 miles to 9.6 miles (assuming the participant travelled from home). Participants’ distance travelled summated to a mean average ± SD of 181.45 miles ± 87.85 (range 22.8–364.8 miles). Thirteen participants (65%) travelled by car, two by bus, one by motorbike/scooter and one participant walked. Three participants travelled via taxi, one of which was through choice due to anxiety of driving and parking. Of the three that travelled by taxi, two reported difficulties relating to funding their journey. In one case, this led to missed appointments due to lack of funds, and the other participant who chose to come by taxi missed several appointments due to dissatisfaction relating to travel re-imbursement.

- Acceptability of participant-reported outcome measures: a total of 17 participants (89.5%) felt questionnaires administered were easy to follow and complete, with the remaining 10.5% (n = 2) being ‘not sure’. All participants (n = 19) felt the number and breadth of questionnaires was appropriate and necessary. Two participants (10.5%) felt more questionnaires were warranted to express further aspects of their condition impacting on their daily life. One participant felt that stiffness should have been measured objectively.

- Acceptability of performance-based outcome measures: a total of 17 participants (89.5%) found the Stroop Test delivered via mobile application straightforward to use and understood what was being asked of them. One participant (5.3%) was ‘not sure’, as they had no memory of performing the test. All participants (n = 19) reported that they would be happy to complete further additional cognitive objective measures in a future trial. All participants (n = 19) felt the tender point examinations were necessary towards assessing their condition and all would be happy for the same examination in a future trial. However, participants admitted they did not want considerable pressure applied at week 6 due to concerns over inducing a FM flare and no longer having the treatment available to aid this.

- Acceptability of audio-recorded semi-structured interviews: sixteen participants (84.2%) underwent audio-recorded semi-structured interviews. Fourteen of these participants found the interviews straightforward and felt comfortable. One participant did not answer and one participant felt a little uncomfortable due to not liking the sound of their voice.

3.4.3. Treatment-Related Feasibility Outcomes

- Acceptability of trial device: when asked to give comment about access and accessibility, six participants (31.6%) did not answer. The remaining 13 participants (68.4%) felt both the trial location and the device itself were easy to access. Constructive comments related to suggestion of a supporting rail for ease of entry and exit onto and off the device and a larger changing space. Two participants (10.5%) were asked to remove their transdermal fentanyl patch for every treatment. One participant managed to re-apply using adhesive dressings. The second participant required a temporary increase in quantity via prescription due to unsuccessful re-application of patches. All participants graded usability and comfort of trial device on a Likert scale from 1 = strongly agree through to 5 = strongly disagree (Figure 5).

- 2.

- Treatment satisfaction: participants were asked to list three words to describe their experience of the ‘light therapy pod’. Positive experiences included: helpful (n = 4), pleasant (n = 3), positive (n = 3), enjoyable (n = 2), comfortable (n = 1), efficient (n = 1), great (n = 1), useful (n = 1), interesting (n = 1), painless (n = 1), quick (n = 1), beneficial (n = 1), easy (n = 1), worthwhile (n = 1) and necessary (n = 1). One negative experience was described with regard to pain impeding ability to make appointments: difficult (n = 1). Low-energy positive emotions were: relaxing (n = 11), calming (n = 3) and soothing (n = 2). High-energy positive emotions were: pain relief (n = 4), warm (n = 3), better memory (n = 2), good mood (n = 2), better sleep (n = 1), more energy (n = 1), less confused (n = 1), reduced headaches (n = 1), clearer mind (n = 1), addictive (n = 1) and fun (n = 1). One future-related description was: hope (n = 1).

- 3.

- Willingness towards future trial: all trial participants were willing to be involved in future research related to this device and all were happy with the prospect of a 50:50 chance of receiving 18 placebo treatments, selected at random, and being ‘blinded’ with goggles.

3.5. Secondary Outcomes

3.5.1. Core Domains: Participant-Reported Outcome Measures

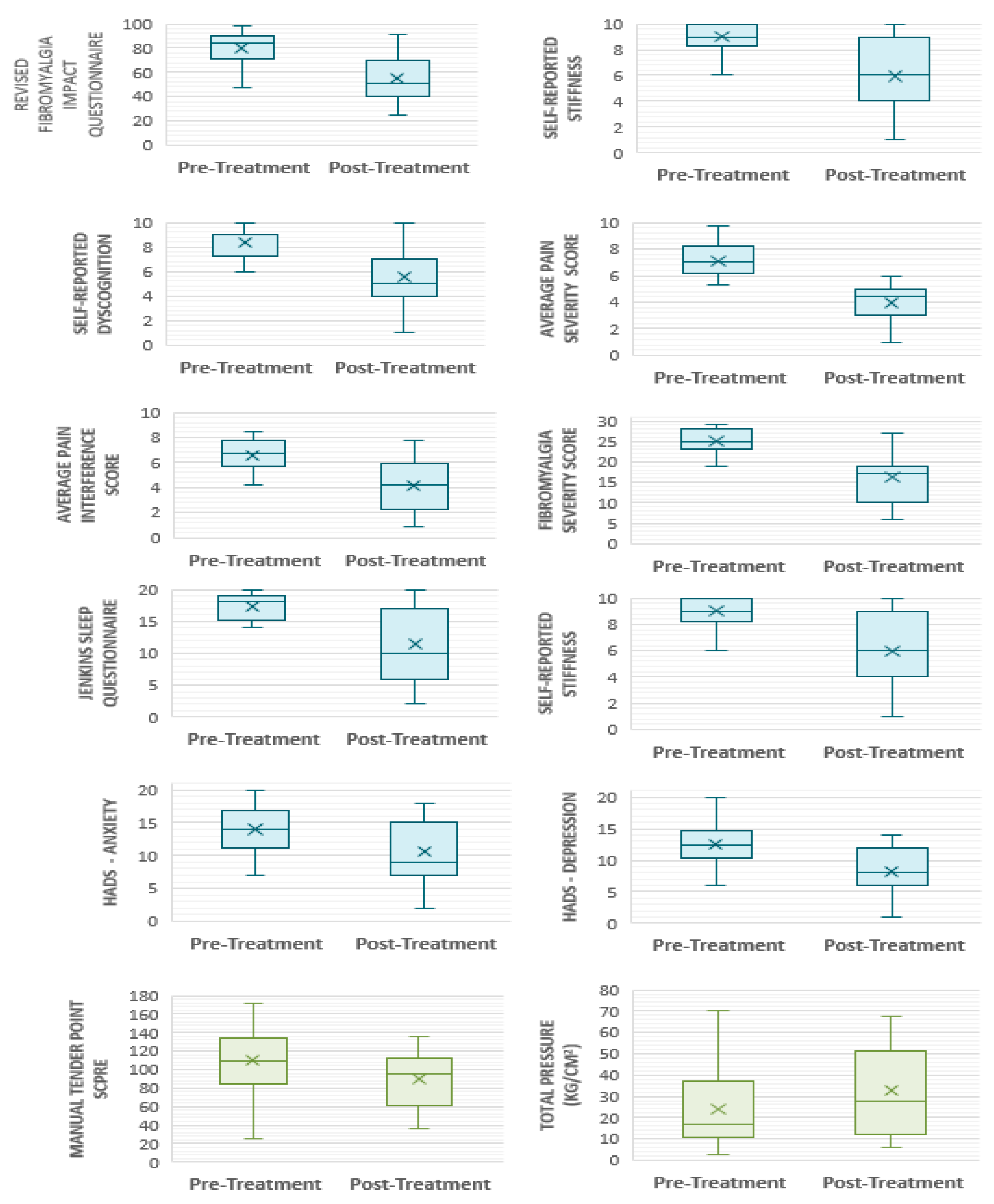

- Multidimensional function: pre-treatment FIQR scores were 79.7 ± 13.26. At week 6, scores had reduced to 55.3 ± 19.72—an improvement of 24.44 ± 20.38 points (p ≤ 0.001). By week 24, scores were 65.68 ± 16.53; an increase compared with week 6 (p = 0.23), but clinically [78] and statistically significantly (p = 0.001) lower compared with baseline scores (Figure 7). FIQR score can be categorised by severity [78]. According to this scale, 17 participants (89.5%) commenced the trial with their FM symptoms having a severe effect on them and their symptoms being very intrusive. Six of the participants (37.5%) who commenced the trial with ‘severe’ FM (score ≥ 59 to 100), had only ‘moderate’ FM (score ≥ 39 to 59) after 6 weeks of PBMT, whilst four (25%) finished with treatment with ‘mild’ FM (score 0 to <39). Seven participants remained in the severe category, albeit all with a lower post-treatment score.

- 2.

- Pain: both pain-intensity and pain-interference scores showed clinically significant improvements post-intervention [78,79,80]. Pre-treatment pain-intensity was 7.08 ± 1.28. Post-treatment pain-intensity was 3.93 ± 1.38. Pain-interference score improved to 4.17 ± 1.99 from a pre-treatment score of 6.59 ± 1.32. A further question (which does not contribute to overall scoring) aims to ascertain the extent of relief from currently used analgesics—with improvements seen at week 6. Baseline perceived analgesic efficacy was 43.5% ± 17.55, rising to 53.89% ± 20.0 by week 6. All participants were confirmed to have FM, reflected in their scores of 25.1 ± 2.86 at baseline (comprised of WPI 15 ± 2.45 and SSS 10.1 ± 1.45). Scores improved to 16.21 ± 5.78 at week 6 (WPI 9.89 ± 4.21; SSS 6.32 ± 2.54). There is no reported MCID (minimal clinically important difference) for the 2016 Fibromyalgia Diagnostic Criteria, rather the American College of Rheumatology recommends use as a severity score in the longitudinal evaluation of participants [61]. When using the tool for its primary purpose—as a diagnostic tool—almost a third of participants (31.6%, n = 6) experienced an improvement in the order of magnitude that they would have been described as ‘negative’ for FM if were being assessed for diagnosis for the first time. At the commencement of each calendar week, each participant reported an average pain score out of 10 according to the NRS for pain for the preceding 7 days. There was a gradual decline in pain scores during the course of the trial. The average pain score reported at Visit 4 was 6.89. The average pain score reported at the start week 6 of treatment was 5.86.

- 3.

- Fatigue: FSS pre-treatment score was 6.30 ± 0.86, reducing to 5.61 ± 1.16 post-treatment.

- 4.

- Sleep disturbance: following six weeks of PBMT in this study sample, JSQ scores exhibited a reduction from additive score of 17.35 ± 1.90 (mean 4.34 ± 0.97) at baseline to 11.53 ± 6.17 (2.91 ± 1.74) post-treatment. The Jenkins Sleep Questionnaire (JSQ) categorises sleep into ‘little sleep disturbance’ and ‘high frequency of sleep disturbance’ [63]. All participants commenced the trial in the high frequency category, that is, difficulty falling to sleep and staying asleep, waking several times per night and feeling worn out after their usual night’s sleep. Ten participants (52.6%) fell into the ‘little sleep disturbance’ category post-intervention. Of those that demonstrated better sleep post-treatment (68.4%, n = 13), all improvements were ≥20% (range 20% to 88.9%), with an overall mean improvement of 33.6%.

- 5.

- Patient global: post-treatment, participants were asked to rate the change to their overall quality of life, symptoms, emotions and activity limitation related to their pain condition. The mean average score was 5.47 ± 1.43. Four participants (21.1%) gave a score of 7. A further question denotes degree of change since commencing the treatment. At week 6, seventeen participants (89.5%) trended toward ‘much better’, whilst two participants scored ‘no change’. No participant trended towards ‘much worse’. By week 24, the mean average score was 3.79 ± 2.1, an indication that participants remained ‘a little better’ and ‘somewhat better’ at this timepoint. Thirteen participants (68.4%) continued to trend toward ‘much better’, five participants (26.3%) felt no change and one participant (5.3%) felt worse. Eleven participants (57.9%) had overall benefits in their condition in the order of ‘moderate’ or ‘substantial’ [79,81], with five participants (26.3%) reporting clinically significant improvements that were still ongoing at 24 weeks.

3.5.2. Core Domains: Performance-Based Outcome Measures

- Tenderness: the majority of participants did not tolerate the recommended pressure application of 4 kg/cm2 [54,68] across most tender points. The results are, therefore, presented according to the maximum pressure tolerated. Prior to commencement of the trial intervention, participants tolerated an average of 1.21 kg/cm2 ± 1.05 across each of the 18 recommended tender points. Post-treatment at week 6, participants tolerated higher pressures of 1.71 kg/cm2 ± 1.16. Average pain scores across 18 tender points (also known as Fibromyalgia Intensity Score or FIS) pre-treatment were 6.35 ± 1.84 compared with 5.17 ± 1.908 post-treatment. Figure 8 depicts the total MTPS score (sum of 18 NRS scores) for the corresponding total pressure tolerated when considering each tender point in isolation. A negative correlation can be seen post-treatment. That is, participants tolerated a higher pressure on examination for a corresponding lower pain score. It is clear that by the end of week 6, participants can tolerate a higher applied pressure for a corresponding lower MTPS score. Of the 342 total points examined pre-treatment, only three participants tolerated a pressure of 4 kg/cm2 across a collective of nine tender points. Post-treatment, five participants tolerated 4 kg/cm2 (27 points between them).

3.5.3. Peripheral Domains: Participant-Reported Outcome Measures

- Anxiety and depression: depression scores post-treatment were 8.21 ± 3.68 compared to 12.5 ± 3.26 at baseline, representing a 34.3% reduction post-treatment. Similarly, anxiety scores exhibited a 24.8% reduction, which were 14 ± 3.71 pre-treatment and 10.53 ± 4.57 post-treatment. The HADS scale categorises anxiety and depression as mild, moderate and severe. A score ≤ 7 denotes non-cases [82]. All but one participant suffered with anxiety and depression at the outset of the trial (42.1% ‘severe’ anxiety; 26.3% ‘severe’ depression). Ten participants (52.6%) moved into a lower severity category of anxiety post-treatment, three of which improved by ≥2 categories. Five participants (26.3%) no longer suffered anxiety post-treatment and were classed as ‘non-cases’; one of which commenced the trial in the ‘severe’ category. Post-treatment, 78.9% of the participants (n = 15) moved into a milder category of depression than at the trial outset. Five participants (26.3%) improved by ≥2 categories, and 36.8% of the participants’ (n = 7) reported having their depressive symptoms resolved, being classed as ‘non-cases’ post-treatment.

- Stiffness scores pre-treatment were 9.05 ± 1.02, compared with 5.95 ± 2.56 post-treatment. Self-reported dyscognition also demonstrated improvement with a pre-treatment value of 8.35 ± 1.31, compared with 5.58 ± 2.56 post-treatment.

3.5.4. Peripheral Domains: Performance-Based Outcome Measures

- Dyscognition: the Stroop Test results are presented according to total correct score and accuracy (%). Total score achieved pre-treatment was 27.4 ± 16.0, compared with 31.21 ± 15.11 post-treatment. Accuracy was similar post-treatment (pre-treatment 85.23 ± 24.06; post-treatment 85.45 ± 24.04). When comparing self-report cognitive impairment to objective measures used, only four participants (21.1%) demonstrated absolute consistency, with a further five participants (26.3%) exhibiting relative consistency. Self-reported memory problems showed an overall mean improvement of 33.2% post-treatment.

3.6. Confidence Intervals and Effect Sizes

3.7. Medication Changes

3.8. Power Calculation

3.9. Harms

4. Discussion

4.1. Preliminary Feasibility Data Show Improvements in All OMERACT FM Domains Following a Course of Whole-Body Photobiomodulation Therapy

4.2. Proposed Biochemical Mechanisms of Photobiomodulation Therapy and Its Relation to FM Pathogenesis

4.3. Whole-Body Treatment Approach Could Be Advantageous in the FM Population

4.4. Limitations

4.5. Recommendations for Future Research and Clinical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Okifuji, A.; Gao, J.; Bokat, C.; Hare, B.D. Management of fibromyalgia syndrome in 2016. Pain Manag. 2016, 6, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooten, W.M.; Townsend, C.O.; Decker, P.A. Gender differences among patients with fibromyalgia undergoing multidisciplinary pain rehabilitation. Pain Med. 2007, 8, 624–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, D.C.; Glass, J.M.; Minear, M.; Crofford, L.J. Cognitive function in fibromyalgia patients. Arthritis Rheum 2001, 44, 2125–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, D.L.; Burckhardt, C.; Crofford, L. Management of fibromyalgia syndrome. JAMA 2004, 292, 2388–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, A.P.; Santo, A.; Berssaneti, A.A.; Matsutani, L.A.; Yuan, S.L.K. Prevalence of fibromyalgia: Literature review update. Rev. Bras. Reum. (Engl. Ed.) 2017, 57, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A.; Dukes, E.; Martin, S.; Edelsberg, J.; Oster, G. Characteristics and healthcare costs of patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Int. J. Clin. Pr. 2007, 61, 1498–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacasse, A.; Bourgault, P.; Choinière, M. Fibromyalgia-related costs and loss of productivity: A substantial societal burden. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2016, 17, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, L.M.; Bennett, R.M.; Crofford, L.J.; Dean, L.E.; Clauw, D.J.; Goldenberg, D.L.; Fitzcharles, M.A.; Paiva, E.S.; Staud, R.; Sarzi-Puttini, P.; et al. AAPT Diagnostic Criteria for Fibromyalgia. J. Pain 2019, 20, 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tugwell, P.; Boers, M.; Brooks, P.; Simon, L.; Strand, V.; Idzerda, L. OMERACT: An international initiative to improve outcome measurement in rheumatology. Trials 2007, 8, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kia, S.; Choy, E. Update on Treatment Guideline in Fibromyalgia Syndrome with Focus on Pharmacology. Biomedicines 2017, 5, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kisselev, S.B.; Moskvin, S.V. The Use of Laser Therapy for Patients with Fibromyalgia: A Critical Literary Review. J. Lasers Med. Sci. 2019, 10, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health, T.L.P. Opioid overdose crisis: Time for a radical rethink. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Chronic Pain (Primary and Secondary) in over 16s: Assessment of all Chronic Pain and Management of Chronic Primary Pain NICE Guideline [NG193]. 2021. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng193 (accessed on 24 May 2021).

- Jack, K.; McLean, S.M.; Moffett, J.K.; Gardiner, E. Barriers to treatment adherence in physiotherapy outpatient clinics: A systematic review. Man. Ther. 2010, 15, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McVeigh, J.G.; Lucas, A.; Hurley, D.A.; Basford, J.R.; Baxter, G.D. Patients’ perceptions of exercise therapy in the treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome: A survey. Musculoskelet. Care 2003, 1, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, R., Jr.; Pergolizzi, J.V.; Puenpatom, R.A.; Summers, K.H. Economic implications of potential drug-drug interactions in chronic pain patients. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2013, 13, 725–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Commonly Used Treatments for Chronic Pain can do more Harm than Good and should not be used, Says NICE in Draft Guidance. 2020. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/news/article/commonly-used-treatments-for-chronic-pain-can-do-more-harm-than-good-and-should-not-be-used-says-nice-in-draft-guidance (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Chung, H.; Dai, T.; Sharma, S.K.; Huang, Y.Y.; Carroll, J.D.; Hamblin, M.R. The nuts and bolts of low-level laser (light) therapy. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2012, 40, 516–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Low-Level Laser Therapy for Preventing or Treating Oral Mucositis Caused by Radiotherapy or Chemotherapy. 2018. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ipg615 (accessed on 18 July 2020).

- Farivar, S.; Malekshahabi, T.; Shiari, R. Biological effects of low level laser therapy. J. Lasers Med. Sci. 2014, 5, 58–62. [Google Scholar]

- Bisset, L.; Coombes, B.; Vicenzino, B. Tennis elbow. BMJ Clin. Evid. 2011, 2011, 1117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carcia, C.R.; Martin, R.L.; Houck, J.; Wukich, D.K. Achilles pain, stiffness, and muscle power deficits: Achilles tendinitis. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2010, 40, A1–A26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, R.T.; Johnson, M.I.; Lopes-Martins, R.A.; Bjordal, J.M. Efficacy of low-level laser therapy in the management of neck pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo or active-treatment controlled trials. Lancet 2009, 374, 1897–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clijsen, R.; Brunner, A.; Barbero, M.; Clarys, P.; Taeymans, J. Effects of low-level laser therapy on pain in patients with musculoskeletal disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2017, 53, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrade, A.L.; Bossini, P.S.; Parizotto, N.A. Use of low level laser therapy to control neuropathic pain: A systematic review. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2016, 164, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deana, N.F.; Zaror, C.; Sandoval, P.; Alves, N. Effectiveness of Low-Level Laser Therapy in Reducing Orthodontic Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pain Res. Manag. 2017, 2017, 8560652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favejee, M.M.; Huisstede, B.M.; Koes, B.W. Frozen shoulder: The effectiveness of conservative and surgical interventions—Systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2011, 45, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazov, G.; Yelland, M.; Emery, J. Low-level laser therapy for chronic non-specific low back pain: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Acupunct. Med. 2016, 34, 328–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haldeman, S.; Carroll, L.; Cassidy, J.D.; Schubert, J.; Nygren, A. The Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders: Executive summary. Spine 2008, 33, S5–S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huisstede, B.M.; Hoogvliet, P.; Franke, T.P.; Randsdorp, M.S.; Koes, B.W. Carpal Tunnel Syndrome: Effectiveness of Physical Therapy and Electrophysical Modalities. An Updated Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2018, 99, 1623–1634.e1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maia, M.L.; Bonjardim, L.R.; Quintans Jde, S.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Maia, L.G.; Conti, P.C. Effect of low-level laser therapy on pain levels in patients with temporomandibular disorders: A systematic review. J. Appl. Oral. Sci. 2012, 20, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Association for the Study of Pain. Myofascial Pain. 2010. Available online: https://s3.amazonaws.com/rdcmsiasp/files/production/public/Content/ContentFolders/GlobalYearAgainstPain2/20092010MusculoskeletalPain/14.%20Myofascial%20Pain%20Fact%20Sheet%20Revised%202017.pdf (accessed on 5 July 2020).

- Raja, S.N.; Carr, D.B.; Cohen, M.; Finnerup, N.B.; Flor, H.; Gibson, S.; Keefe, F.J.; Mogil, J.S.; Ringkamp, M.; Sluka, K.A.; et al. The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: Concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain 2020, 161, 1976–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rooney, S.; McFadyen, D.A.; Wood, D.L.; Moffat, D.F.; Paul, P.L. Minimally important difference of the fatigue severity scale and modified fatigue impact scale in people with multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2019, 35, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zadik, Y.; Arany, P.R.; Fregnani, E.R.; Bossi, P.; Antunes, H.S.; Bensadoun, R.J.; Gueiros, L.A.; Majorana, A.; Nair, R.G.; Ranna, V.; et al. Systematic review of photobiomodulation for the management of oral mucositis in cancer patients and clinical practice guidelines. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 3969–3983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzmaurice, B.; Heneghan, N.R.; Rayen, A.; Soundy, A. Whole-body photobiomodulation therapy for chronic pain: A protocol for a feasibility trial. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e060058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Lima, F.; Barrett, D.W. Augmentation of cognitive brain functions with transcranial lasers. Front Syst. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- THOR Photomedicine Ltd., T.P. Novothor. 2019–2023. Available online: https://www.novothor.com/?utm_source=google&utm_medium=cpc&keyword=novothor&utm_campaign=602860951&gad=1&gclid=CjwKCAjww7KmBhAyEiwA5-PUSgUI0Ry2inGx2zfW936PictCTP41gfbKRfJXWx3lQ7m5qovrNDs8VBoCnlUQAvD_BwE (accessed on 8 December 2021).

- Eldridge, S.M.; Chan, C.L.; Campbell, M.J.; Bond, C.M.; Hopewell, S.; Thabane, L.; Lancaster, G.A. CONSORT 2010 statement: Extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ 2016, 355, i5239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvert, M.; King, M.; Mercieca-Bebber, R.; Aiyegbusi, O.; Kyte, D.; Slade, A.; Chan, A.W.; Basch, E.; Bell, J.; Bennett, A.; et al. SPIRIT-PRO Extension explanation and elaboration: Guidelines for inclusion of patient-reported outcomes in protocols of clinical trials. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e045105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, T.C.; Glasziou, P.P.; Boutron, I.; Milne, R.; Perera, R.; Moher, D.; Altman, D.G.; Barbour, V.; Macdonald, H.; Johnston, M.; et al. Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014, 348, g1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mease, P.; Arnold, L.M.; Choy, E.H.; Clauw, D.J.; Crofford, L.J.; Glass, J.M.; Martin, S.A.; Morea, J.; Simon, L.; Strand, C.V.; et al. Fibromyalgia syndrome module at OMERACT 9: Domain construct. J. Rheumatol. 2009, 36, 2318–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umay, E.; Gundogdu, I.; Ozturk, E.A. What happens to muscles in fibromyalgia syndrome. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 189, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranidharan, G.W.A.; Wilson, S.; Cameron, P.; Tan, T. Outcome Measures. British Pain Society, Faculty of Pain Medicine of the Royal College of Anaesthetists. Available online: https://www.britishpainsociety.org/static/uploads/resources/files/Outcome_Measures_January_2019.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2021).

- Bell, T.; Trost, Z.; Buelow, M.T.; Clay, O.; Younger, J.; Moore, D.; Crowe, M. Meta-analysis of cognitive performance in fibromyalgia. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2018, 40, 698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.V.; Hung, C.H.; Sun, W.Z.; Wu, W.T.; Lai, C.L.; Han, D.S.; Chen, C.C. Evaluating soreness symptoms of fibromyalgia: Establishment and validation of the Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire with Integration of Soreness Assessment. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2020, 119, 1211–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Din, N.C. Computerized Stroop Tests: A Review. Psychol. Med. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Duruoz, M.T.; Ulutatar, F.; Ozturk, E.C.; Unal-Ulutatar, C.; Sanal Toprak, C.; Kayhan, O. Assessment of the validity and reliability of the Jenkins Sleep Scale in ankylosing spondylitis. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2019, 22, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvez-Sánchez, C.M.; de la Coba, P.; Duschek, S.; Del Paso, G.A.R. Reliability, Factor Structure and Predictive Validity of the Widespread Pain Index and Symptom Severity Scales of the 2010 American College of Rheumatology Criteria of Fibromyalgia. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, O.K.; Callesen, J.; Nielsen, M.G.; Ellingsen, T. Reproducibility of tender point examination in chronic low back pain patients as measured by intrarater and inter-rater reliability and agreement: A validation study. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e002532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendoza, T.; Mayne, T.; Rublee, D.; Cleeland, C. Reliability and validity of a modified Brief Pain Inventory short form in patients with osteoarthritis. Eur. J. Pain 2006, 10, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taulaniemi, A.; Kankaanpää, M.; Rinne, M.; Tokola, K.; Parkkari, J.; Suni, J.H. Fear-avoidance beliefs are associated with exercise adherence: Secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial (RCT) among female healthcare workers with recurrent low back pain. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effect Size Calculator for t-Test. Available online: https://www.socscistatistics.com/effectsize/default3.aspx (accessed on 23 September 2022).

- Boomershine, C.S. A comprehensive evaluation of standardized assessment tools in the diagnosis of fibromyalgia and in the assessment of fibromyalgia severity. Pain Res. Treat. 2012, 2012, 653714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R.M.; Friend, R.; Jones, K.D.; Ward, R.; Han, B.K.; Ross, R.L. The Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQR): Validation and psychometric properties. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2009, 11, R120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleeland, C.S.; Ryan, K.M. Pain assessment: Global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 1994, 23, 129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, L.M.; Goldenberg, D.L.; Stanford, S.B.; Lalonde, J.K.; Sandhu, H.S.; Keck, P.E., Jr.; Welge, J.A.; Bishop, F.; Stanford, K.E.; Hess, E.V.; et al. Gabapentin in the treatment of fibromyalgia: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 56, 1336–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleeland, C. The Brief Pain Inventory User Guide. 2009. Available online: https://www.mdanderson.org/documents/Departments-and-Divisions/Symptom-Research/BPI_UserGuide.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2022).

- Wolfe, F.; Clauw, D.J.; Fitzcharles, M.A.; Goldenberg, D.L.; Katz, R.S.; Mease, P.; Russell, A.S.; Russell, I.J.; Winfield, J.B.; Yunus, M.B. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res. 2010, 62, 600–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, F.; Smythe, H.A.; Yunus, M.B.; Bennett, R.M.; Bombardier, C.; Goldenberg, D.L.; Tugwell, P.; Campbell, S.M.; Abeles, M.; Clark, P.; et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1990, 33, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfe, F.; Clauw, D.J.; Fitzcharles, M.A.; Goldenberg, D.L.; Häuser, W.; Katz, R.L.; Mease, P.J.; Russell, A.S.; Russell, I.J.; Walitt, B. Revisions to the 2010/2011 fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2016, 46, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krupp, L.B.; LaRocca, N.G.; Muir-Nash, J.; Steinberg, A.D. The fatigue severity scale. Application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch. Neurol. 1989, 46, 1121–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, C.D.; Stanton, B.A.; Niemcryk, S.J.; Rose, R.M. A scale for the estimation of sleep problems in clinical research. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1988, 41, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, H.; Bolton, J. Assessing the clinical significance of change scores recorded on subjective outcome measures. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 2004, 27, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworkin, R.H.; Turk, D.C.; Wyrwich, K.W.; Beaton, D.; Cleeland, C.S.; Farrar, J.T.; Haythornthwaite, J.A.; Jensen, M.P.; Kerns, R.D.; Ader, D.N.; et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J. Pain 2008, 9, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, A.F. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Occup. Med. 2014, 64, 393–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okifuji, A.; Turk, D.C.; Sinclair, J.D.; Starz, T.W.; Marcus, D.A. A standardized manual tender point survey. I. Development and determination of a threshold point for the identification of positive tender points in fibromyalgia syndrome. J. Rheumatol. 1997, 24, 377–383. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.L.; Huang, C.J.; Fang, S.C.; Ko, L.H.; Tsai, P.S. Cognitive Impairment in Fibromyalgia: A Meta-Analysis of Case-Control Studies. Psychosom. Med. 2018, 80, 432–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew Novak. Stroop Test for Research App: AppAdvice. 2018. Available online: https://appadvice.com/app/stroop-test-for-research/1141685066 (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Kieser, M.; Wassmer, G. On the Use of the Upper Confidence Limit for the Variance from a Pilot Sample for Sample Size Determination. Biom. J. 1996, 38, 941–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, G.A.; Thabane, L. Guidelines for reporting non-randomised pilot and feasibility studies. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2019, 5, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M.; Bromley, K.; Sutton, C.J.; McCray, G.; Myers, H.L.; Lancaster, G.A. Determining sample size for progression criteria for pragmatic pilot RCTs: The hypothesis test strikes back! Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2021, 7, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies: Guided by Information Power. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, C.G.; Carter, R.E.; Nietert, P.J.; Stewart, P.W. Recommendations for planning pilot studies in clinical and translational research. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2011, 4, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. The t Test For Means (Chapter 2). In Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1988; p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R.M.; Bushmakin, A.G.; Cappelleri, J.C.; Zlateva, G.; Sadosky, A.B. Minimal clinically important difference in the fibromyalgia impact questionnaire. J. Rheumatol. 2009, 36, 1304–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mease, P.J.; Spaeth, M.; Clauw, D.J.; Arnold, L.M.; Bradley, L.A.; Russell, I.J.; Kajdasz, D.K.; Walker, D.J.; Chappell, A.S. Estimation of minimum clinically important difference for pain in fibromyalgia. Arthritis Care Res. 2011, 63, 821–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poquet, N.; Lin, C. The Brief Pain Inventory (BPI). J. Physiother. 2016, 62, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surendran, S.; Mithun, C.B. FRI0647 Estimation of minimum clinically important difference in fibromyalgia for fiqr using bpi as the anchor measure. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2018, 77, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snaith, R.P. The Hospital Anxiety And Depression Scale. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 2003, 1, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, A. Exploring Assumptions. In Discovering Statistics Using SPSS, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2009; pp. 138–139. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, S.-W.; Hong, C.-H.; Shih, M.-C.; Tam, K.-W.; Huang, Y.-H.; Kuan, Y.-C. Low-Level Laser Therapy for Fibromyalgia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pain Physician. 2019, 22, 241–254. [Google Scholar]

- Honda, Y.; Sakamoto, J.; Hamaue, Y.; Kataoka, H.; Kondo, Y.; Sasabe, R.; Goto, K.; Fukushima, T.; Oga, S.; Sasaki, R.; et al. Effects of Physical-Agent Pain Relief Modalities for Fibromyalgia Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Pain Res. Manag. 2018, 2018, 2930632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, M.P.; Motta, B.N.; Monteiro, M.C.; Cecatto, R.B. Quality of life (QoL) after laser therapy for the management of fibromyalgia: A systematic review. Mech. Tech. Photodyn. Ther. Photobiomodul. 2021, 11628, 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, B.K.; Piault, E.C.; Lai, C.; Sarzi-Puttini, P. Assessing sleep in fibromyalgia: Investigation of an alternative scoring method for the Jenkins Sleep Scale based on data from randomized controlled studies. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2010, 28, S100–S109. [Google Scholar]

- Mathias, S.D.; Crosby, R.D.; Qian, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Dansey, R.; Chung, K. Estimating minimally important differences for the worst pain rating of the Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form. J. Support. Oncol. 2011, 9, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordin, Å.; Taft, C.; Lundgren-Nilsson, Å.; Dencker, A. Minimal important differences for fatigue patient reported outcome measures-a systematic review. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2016, 16, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.C.; Chen, H.; Xu, W.T.; Song, Y.Y.; Gu, Y.H.; Ni, G.X. Acupuncture therapy for fibromyalgia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Pain Res. 2019, 12, 527–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheijen, E.J.A.; Munts, A.G.; van Haagen, O.B.H.A.M.; de Vries, D.; Vleggeert-Lankamp, C.L.A. The Outcome of Epidural Injections in Lumbar Radiculopathy Is Not Dependent on the Presence of Disc Herniation on Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Assessment of Short-Term and Long-Term Efficacy. World Neurosurg. 2021, 148, e643–e649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfarlane, G.J.; Kronisch, C.; Dean, L.E.; Atzeni, F.; Häuser, W.; Fluß, E.; Choy, E.; Kosek, E.; Amris, K.; Branco, J.; et al. EULAR revised recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2017, 76, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, A.M.; Geenen, R.; Castilho, P.; da Silva, J.A.P. Progress towards improved non-pharmacological management of fibromyalgia. Jt. Bone. Spine 2020, 87, 377–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.K.; Harris, K.; Hadi, S.; Chow, E. What should be the optimal cut points for mild, moderate, and severe pain? J. Palliat. Med. 2007, 10, 1338–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, J.; Lewis, M. The size of a pilot study for a clinical trial should be calculated in relation to considerations of precision and efficiency. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2012, 65, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Ledesma, S.; Carroll, J.; González-Muñoz, A.; Pruimboom, L.; Burton, P. Changes in Circadian Variations in Blood Pressure, Pain Pressure Threshold and the Elasticity of Tissue after a Whole-Body Photobiomodulation Treatment in Patients with Fibromyalgia: A Tripled-Blinded Randomized Clinical Trial. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerdal, A. Fatigue Severity Scale. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Maggino, F., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Billones, R.; Liwang, J.K.; Butler, K.; Graves, L.; Saligan, L.N. Dissecting the fatigue experience: A scoping review of fatigue definitions, dimensions, and measures in non-oncologic medical conditions. Brain. Behav. Immun. Health 2021, 15, 100266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutra, Y.M.; Malta, E.S.; Elias, A.S.; Broatch, J.R.; Zagatto, A.M. Deconstructing the Ergogenic Effects of Photobiomodulation: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of its Efficacy in Improving Mode-Specific Exercise Performance in Humans. Sports Med. 2022, 52, 2733–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferlito, J.V.; Ferlito, M.V.; Leal-Junior, E.C.P.; Tomazoni, S.S.; De Marchi, T. Comparison between cryotherapy and photobiomodulation in muscle recovery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lasers Med. Sci. 2022, 37, 1375–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nampo, F.K.; Cavalheri, V.; Dos Santos Soares, F.; de Paula Ramos, S.; Camargo, E.A. Low-level phototherapy to improve exercise capacity and muscle performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lasers Med. Sci. 2016, 31, 1957–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanin, A.A.; Verhagen, E.; Barboza, S.D.; Costa, L.O.P.; Leal-Junior, E.C.P. Photobiomodulation therapy for the improvement of muscular performance and reduction of muscular fatigue associated with exercise in healthy people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lasers Med. Sci. 2018, 33, 181–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larun, L.; Brurberg, K.G.; Odgaard-Jensen, J.; Price, J.R. Exercise therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 10, Cd003200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luurssen-Masurel, N.; Weel, A.E.A.M.; Hazes, J.M.W.; de Jong, P.H.P. The impact of different (rheumatoid) arthritis phenotypes on patients’ lives. Rheumatology 2021, 60, 3716–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Askalsky, P.; Iosifescu, D.V. Transcranial Photobiomodulation For The Management of Depression: Current Perspectives. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2019, 15, 3255–3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Menéndez, A.; Marcos-Nistal, M.; Méndez, M.; Arias, J.L. Photobiomodulation as a promising new tool in the management of psychological disorders: A systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 119, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehpour, F.; Mahmoudi, J.; Kamari, F.; Sadigh-Eteghad, S.; Rasta, S.H.; Hamblin, M.R. Brain Photobiomodulation Therapy: A Narrative Review. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 55, 6601–6636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehpour, F.; Khademi, M.; Hamblin, M.R. Photobiomodulation Therapy for Dementia: A Systematic Review of Pre-Clinical and Clinical Studies. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2021, 83, 1431–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehpour, F.; Majdi, A.; Pazhuhi, M.; Ghasemi, F.; Khademi, M.; Pashazadeh, F.; Hamblin, M.R.; Cassano, P. Transcranial Photobiomodulation Improves Cognitive Performance in Young Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2019, 37, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero, M.D.; de Miguel, M.; Carmona-López, I.; Bonal, P.; Campa, F.; Moreno-Fernández, A.M. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in fibromyalgia. Neuro. Endocrinol. Lett. 2010, 31, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sui, B.D.; Xu, T.Q.; Liu, J.W.; Wei, W.; Zheng, C.X.; Guo, B.L.; Wang, Y.Y.; Yang, Y.L. Understanding the role of mitochondria in the pathogenesis of chronic pain. Postgrad. Med. J. 2013, 89, 709–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousuf, M.S.; Maguire, A.D.; Simmen, T.; Kerr, B.J. Endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria interplay in chronic pain: The calcium connection. Mol. Pain 2020, 16, 1744806920946889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Santos, R.C.; Souza Guedes, K.; de Sousa Pinto, J.M.; Oliveira, M.F. Acute low-level laser therapy effects on peripheral muscle strength and resistance in patients with fibromyalgia. Lasers Med. Sci. 2020, 35, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dompe, C.; Moncrieff, L.; Matys, J.; Grzech-Leśniak, K.; Kocherova, I.; Bryja, A.; Bruska, M.; Dominiak, M.; Mozdziak, P.; Skiba, T.H.I.; et al. Photobiomodulation-Underlying Mechanism and Clinical Applications. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Junior, E.C.; Lopes-Martins, R.A.; Frigo, L.; De Marchi, T.; Rossi, R.P.; de Godoi, V.; Tomazoni, S.S.; Silva, D.P.; Basso, M.; Filho, P.L.; et al. Effects of low-level laser therapy (LLLT) in the development of exercise-induced skeletal muscle fatigue and changes in biochemical markers related to postexercise recovery. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2010, 40, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagatto, A.M.; Dutra, Y.M.; Lira, F.S.; Antunes, B.M.; Faustini, J.B.; Malta, E.S.; Lopes, V.H.F.; de Poli, R.A.B.; Brisola, G.M.P.; Dos Santos, G.V.; et al. Full Body Photobiomodulation Therapy to Induce Faster Muscle Recovery in Water Polo Athletes: Preliminary Results. Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2020, 38, 766–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.W.; Wong, C.S.; Hui, G.K.; Chung, E.K.; Wong, S.H. Fibromyalgia: Is it a neuropathic pain? Pain Manag. 2018, 8, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alayat, M.S.M.; Battecha, K.H.; Elsodany, A.M.; Alzahrani, O.A.; Alqurashi, A.K.A.; Jawa, A.T.; Alharthi, Y.S. Effectiveness of Photobiomodulation Therapy in the Treatment of Myofascial Pain Syndrome of the Upper Trapezius Muscle: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser. Surg. 2022, 40, 661–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rentz, L.E.; Bryner, R.W.; Ramadan, J.; Rezai, A.; Galster, S.M. Full-Body Photobiomodulation Therapy Is Associated with Reduced Sleep Durations and Augmented Cardiorespiratory Indicators of Recovery. Sports 2022, 10, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobaldini, E.; Costantino, G.; Solbiati, M.; Cogliati, C.; Kara, T.; Nobili, L.; Montano, N. Sleep, sleep deprivation, autonomic nervous system and cardiovascular diseases. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 74, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoccoli, G.; Amici, R. Sleep and autonomic nervous system. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2020, 15, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossema, E.R.; van Middendorp, H.; Jacobs, J.W.G.; Bijlsma, J.W.J.; Geenen, R. Influence of Weather on Daily Symptoms of Pain and Fatigue in Female Patients With Fibromyalgia: A Multilevel Regression Analysis. Arthritis Care Res. 2013, 65, 1019–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagglund, K.J.; Deuser, W.E.; Buckelew, S.P.; Hewett, J.; Kay, D.R. Weather, beliefs about weather, and disease severity among patients with fibromyalgia. Arthritis Care Res. 1994, 7, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, K.; Miki, K.; Hayashi, N.; Hashimoto, R.; Yukioka, M. Weather sensitivity associated with quality of life in patients with fibromyalgia. BMC Rheumatol. 2021, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincent, A.; Whipple, M.O.; Rhudy, L.M. Fibromyalgia Flares: A Qualitative Analysis. Pain Med. 2016, 17, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darnall, B.D.; Sturgeon, J.A.; Kao, M.-C.; Hah, J.M.; Mackey, S.C. From Catastrophizing to Recovery: A pilot study of a single-session treatment for pain catastrophizing. J. Pain Res. 2014, 7, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankovsky, T.; Lynch, M.; Clark, A.; Sawynok, J.; Sullivan, M.J. Pain catastrophizing predicts poor response to topical analgesics in patients with neuropathic pain. Pain Res. Manag. 2012, 17, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takasaki, H.; Treleaven, J. Construct validity and test-retest reliability of the Fatigue Severity Scale in people with chronic neck pain. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2013, 94, 1328–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartley, E.J.; Robinson, M.E.; Staud, R. Pain and Fatigue Variability Patterns Distinguish Subgroups of Fibromyalgia Patients. J. Pain 2018, 19, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L.M.; Zautra, A.J.; Davis, M.C. The role of illness uncertainty on coping with fibromyalgia symptoms. Health Psychol. 2006, 25, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basford, J.R.; An, K.N. New techniques for the quantification of fibromyalgia and myofascial pain. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2009, 13, 376–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genç, A.; Kuş, U.; Agus, A.; Kıymaz, H.M.; Bozdağ, O.; Kurtaiş Aytür, Y.; Kutlay, Ş. The Relationship Between the Tender Point Ultrasound Shear Wave Elastography Velocities and the Symptoms and Quality of Life in Fibromyalgia Syndrome. J. Ank. Univ. Fac. Med. 2019, 72, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karayol, K.C.; Karayol, S.S. A comparison of visual analog scale and shear-wave ultrasound elastography data in fibromyalgia patients and the normal population. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2021, 33, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roots, J.; Trajano, G.S.; Fontanarosa, D. Ultrasound elastography in the assessment of post-stroke muscle stiffness: A systematic review. Insights Imaging 2022, 13, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skivington, K.; Matthews, L.; Simpson, S.A.; Craig, P.; Baird, J.; Blazeby, J.M.; Boyd, K.A.; Craig, N.; French, D.P.; McIntosh, E.; et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: Update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2021, 374, n2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjordal, J.M.; Johnson, M.I.; Iversen, V.; Aimbire, F.; Lopes-Martins, R.A. Low-level laser therapy in acute pain: A systematic review of possible mechanisms of action and clinical effects in randomized placebo-controlled trials. Photomed. Laser. Surg. 2006, 24, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdul, A.J.; Ghai, B.; Bansal, D.; Sachdeva, N.; Bhansali, A.; Dhatt, S.S. Hypothalamic Pituitary Adrenocortical Axis Suppression following a Single Epidural Injection of Methylprednisolone Acetate. Pain Physician. 2017, 20, E991–E1001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Campos, T.M.; do Prado Tavares Silva, C.A.; Sobral, A.P.T.; Sobral, S.S.; Rodrigues, M.F.S.D.; Bussadori, S.K.; Fernandes, K.P.S.; Mesquita-Ferrari, R.A.; Horliana, A.C.R.T.; Motta, L.J. Photobiomodulation in oral mucositis in patients with head and neck cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis followed by a cost-effectiveness analysis. Support. Care Cancer Off. J. Multinatl. Assoc. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 5649–5659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kauark-Fontes, E.; Rodrigues-Oliveira, L.; Epstein, J.B.; Faria, K.M.; Araújo, A.L.D.; Gueiros, L.A.M.; Migliorati, C.A.; Salloum, R.G.; Burton, P.; Carroll, J.; et al. Cost-effectiveness of photobiomodulation therapy for the prevention and management of cancer treatment toxicities: A systematic review. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 2875–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobral, A.P.; Sobral, S.S.; Campos, T.M.; Horliana, A.C.; Fernandes, K.P.; Bussadori, S.K.; Motta, L.J. Photobiomodulation and myofascial temporomandibular disorder: Systematic review and meta-analysis followed by cost-effectiveness analysis. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2021, 13, e724–e732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Procedures | Telephone Call | Baseline Visit | First Visit | Visit 2–Visit 17 | Final Visit | 6-Month Follow-Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eligibility Assessment | ✓ | |||||

| Informed consent | ✓ | |||||

| Blood Tests: Full blood count, Urea and electrolytes, Liver function tests, HbA1c (if diabetic) | ||||||

| Demographics: Age, Gender, Marital status, Employment status, Educational level, Ethnicity | ✓ | |||||

| Medical History: Chronic pain symptom duration, Co-morbidities, Medications | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Measurements: Height, Weight, BMI, Blood pressure, Heart rate, Oxygen saturations | ✓ | ✓ ✓ | ||||

| Participant-reported outcomes measures (PROMs): Brief Pain Inventory Widespread Pain Index/Symptom Severity Score Fatigue Severity Scale Jenkins Sleep Questionnaire Patient Global Impression of Change Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale | ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ | ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ | ✓ ✓ | |||

| Performance-based outcome measures (PBOMs): Tender Point Count Stroop Test | ✓ ✓ | ✓ ✓ | ||||

| Treatment | ✓ ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Weekly Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) Participant-reported experience measure (PREM) | ✓ | ✓ ✓ ✓ | ||||

| Audio-recorded qualitative interviews (optional) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ ✓ |

| Brief Name |

|

| Why |

|

| What |

|

| Who provided |

|

| How |

|

| Where |

|

| When and how much |

|

| Tailoring |

|

| Modifications |

|

| How well |

|

| NovoTHOR® Parameters | Unit | |

|---|---|---|

| Wavelengths of red and near-infrared (NIR) LEDs 50:50 ratio | 660 850 | nm nm |

| Number of LEDs | 2400 | |

| Power emitted per LED | 0.289 | W |

| Beam area per LED (at the lens/skin contact surface) | 12.0 | cm2 |

| Total Power emitted | 694 | W |

| Total Area of NovoTHOR® emitting surfaces | 26,740 | cm2 |

| Treatment Time | 1200 | s |

| Continuous Wave (CW) (not pulsed) | CW | |

| Irradiance | 0.028 | W/cm2 |

| Fluence | 33.6 | J/cm2 |

| OMERACT Domain and Outcome Measures | Tool Background, Use and Scoring |

|---|---|

| ‘Core’ Domains: | |

| Multidimensional function FIQR (i) (2009, replacing FIQ) | Recommended outcome measure in assessment of ‘multidimensional function’ or health-related quality of life [54]. A total of 21 questions across 3 domains: ‘function’, ‘overall impact’, ‘symptoms’. Each question requires a score based on an 11-point NRS pertaining to previous seven days, with a score of 0 being the ‘best’ and 10 being ‘worst’. Administrator calculates overall score. Nine questions from Domain 1 are totalled and divided by 3. Two questions from Domain 2 are simply added. Ten questions from Domain 3 are totalled and divided by 2. The final sum of resulting 3 figures represents the total (0 to 100). Higher scores indicate increased severity of FM [55]. |

| Pain BPI-SF (ii) (1994) | Distinguishes pain into two components in preceding 24 h—pain intensity and pain interference [56]. The recommended pain assessment tool in FM clinical trials [54]. ‘Sensory dimension’: asked to rate ‘worst’, ‘least’, ‘average’, ‘pain now’ on 11-point NRS. ‘Reactive dimension’: score extent pain has interfered with mood, walking and other physical activity, work, social activity, relations with others, and sleep (0 = ‘does not interfere’, 10 = ‘completely interferes’) [56]. Four pain-intensity and seven pain-interference results averaged to give overall pain-intensity score and pain-interference score (0 to 10), respectively [57,58,59]. |

| WPI + SSS (iii) (2010, updated 2016) | Updated diagnostic tool and a potential alternative [59] to original tender point examination, 1990 [60]. WPI: tick painful anatomical areas in preceding week. Nineteen areas are listed across 5 anatomical regions; 4 of which need to be ‘positive’ for an initial diagnosis of FM to be met. SSS: scored out of maximum of 12. Encompasses array of symptoms—user asked to report their presence and/or severity. Total potential combined WPI-SSS score is 31—higher scores indicate more severe FM [59]. Updated 2016 version: for user to be positive for FM diagnosis must score WPI ≥ 7 and SSS ≥ 5, or WPI 4–6 and SSS ≥ 9 [61]. |

| Fatigue FSS (iv) (1989) | Unidimensional generic fatigue rating scale [62], emphasises functional impact of fatigue [63]. The recommended fatigue assessment tool for FM [54]. Nine fatigue-related questions, each scored on a 7-point Likert agreement scale (1 to 7). Resultant score is average of 9 scores, with maximum possible score of 7—indicating the most severe fatigue-related symptoms and intrusiveness. |

| Sleep disturbance JSQ (v) (1988) | Four-item self-report questionnaire designed to measure frequency of sleep problems in past month. The recommended assessment tool to evaluate sleep in FM patients [54]. A 5-point Likert scale (0 = ‘not at all’ to 5 = ‘22–31 days’) was utilised to evaluate the number of days/month that specific sleep-related issues occur (trouble falling and staying asleep, waking up several times/night, waking up after usual amount of sleep feeling tired and worn out). Maximum possible score is 20. Higher scores indicate higher frequency of sleep problems [64]. |

| Patient Global PGIC (vi) (1970s) | Self-report global change questionnaire: 7-point NRS (1 to 7) to determine degree of change following a treatment from patients’ own perspective. Score of ‘1’ indicates either no change or worsening symptoms since treatment. A ‘7’ indicates the patient feels ‘great deal better, considerable improvement that has made all the difference’ [65]. IMMPACT (Initiative on Methods, Measurement and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials) recommended for evaluating participant ratings of overall improvement in pain treatment trials [65]. Specifically recommended in the assessment of global improvement of FM patients in conjunction with the FIQR [54]. |

| ‘Peripheral’ Domains: | |

| Anxiety HADS (vii) (1983) Anxiety subsection (HADS-A) | A 14-item measure: each item rated on a 4-point severity scale (0 to 3). HADS-A subscales: comprised of 7 items. Acknowledged to have been used in FM trials assessing medication efficacy [54]. |

| Depression HADS (vii) Depression subsection (HADS-D) | HADS-D subscales: comprised of 7 items. Scores range from 0 to 21. Higher scores indicate more severe symptoms [66,67]. The recommended tool for assessment of depressive symptoms in FM patients [54]. |

| Stiffness Subsection of FIQR (i) | |

| Dyscognition Subsection of FIQR (i) |

| OMERACT Domain and Outcome Measures | Tool Background, Use and Scoring |

|---|---|

| ‘Core’ Domains: | |

| Tenderness Tender Point Examination (1990) | Manual Tender Point Survey/Fibromyalgia Intensity Score (MTPS/FIS) method is validated for FM population [68]. The currently recommended tenderness assessment for FM trials [54]. Eighteen specific tender points (9 bilateral anatomical areas) identified by American College of Rheumatology in 1990 [60]. Assessed with hand-held Wagner FORCE TENTM FDX pressure algometer—incremental increase up to a maximum of 4 kg/cm2. Pain severity rated at each point according to verbal NRS, with NRS ≥ 2 ‘positive’ for a tender point. Anatomical points: low cervical (C5-C7); 2nd rib (2nd costochondral junction); greater trochanter (posterior to trochanteric prominence); knee (at medial fat pad proximal to joint line); occiput (at suboccipital muscle insertions); trapezius (a midpoint of upper border), supraspinatus (above scapular spine near medial border), lateral epicondyle (2 cm distal to epicondyles); gluteal (upper outer quadrants of buttocks in anterior fold of muscle). |

| ‘Peripheral’ Domains: | |

| Dyscognition Stroop Test (1935, original) | Selected in attempt to address the cognitive domains of inhibitory control, processing speed and memory, which have been shown to be the most significant cognitive complaints in the FM population [45,69]. The Stroop Test for Research application [70] is a computer-based test, performed via mobile application in the current study. A series of colours are spelt out on the screen; blue, red, yellow, green. Each time the word appears, it is presented in a different colour; blue, red, yellow or green. Timed task over 60 s, user required to select correct colour of word. Scored by number of correct answers. No marks lost for incorrect answers. |

| Demographics and Characteristics | n (%) | Mean ± SD | Median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex Female Male | 14 (70) 6 (30) | ||

| Age (years) | 47.3 ± 10.9 | 49 (41–53) | |

| Symptom duration (years) | 15.6 ± 7.7 | 14.5 (10–20) | |

| Marital status Married Single Divorced Co-habiting Civil partnership | 10 (50) 6 (30) 1 (5) 2 (10) 1 (5) | ||

| Employment status Employed full-time Employed part-time Self-employed Unemployed (looking for work) Unemployed (not looking for work) Sick leave Retired | 4 (20) 1 (5) 2 (10) 1 (5) 7 (35) 1 (5) 4 (20) | ||

| Education level Some secondary school Completed secondary school Completed further education (sixth form) Higher education | 1 (5) 2 (10) 1 (5) 16 (80) | ||

| Ethnicity Asian or Asian British Black British White British | 5 (25) 1 (5) 14 (70) | ||

| Measurements Height (cm) Weight (kg) BMI ((kg/m2) Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) Heart rate Oxygen saturations (%) | 166 ± 10.1 87.9 ± 19.1 31.5 ± 5.9 136 ± 20.9 86 ± 10.9 79 ± 12.0 98 ± 1.0 |

| Outcome Measure | Mean Improvement (95% CI) | Cohen’s d Effect Size |

|---|---|---|

| Participant-reported outcome measures | ||

| Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire FIQR Stiffness FIQR Dyscognition | 24.44 (15.27 to 33.60) * 3.11 (2.05 to 4.16) 2.74 (1.48 to 3.99) | 1.49 * 1.59 1.38 |

| Brief Pain Inventory—Short Form BPI Pain Intensity BPI Pain Interference | 3.01 (2.38 to 3.64) 2.35 (1.31 to 3.39) | 2.37 1.43 |

| Fibromyalgia Severity Score | 8.68 (5.61 to 11.76) | 1.95 |

| Fatigue Severity Scale | 0.67 (0.04 to 1.39) | 0.68 |

| Jenkins Sleep Questionnaire | 5.68 (2.84 to 8.53) | 1.27 |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Score HADS-A HADS-D | 3.47 (2.02 to 4.93) 4.21 (2.65 to 5.77) | 0.83 1.23 |

| Performance-based outcome measures | ||

| Tender Point Examination Fibromyalgia Intensity Score Total Pressure tolerated (kg/cm2) | 1.08 (−0.03 to 2.19) 0.57 (0.16 to 0.99) | 0.52 0.49 |

| Stroop Test Total Score Accuracy (%) | 4.11 (0.61 to 7.60) 0.70 (−7.21 to 8.61) | 0.24 0.01 |

| Outcome Measure | Mean Improvement (95% CI) | Cohen’s d Effect Size |

|---|---|---|

| Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire Week 6/Week 24 Baseline/Week 24 | −10.41 (8.98 to 11.85) * 14.02 (12.55 to 15.49) ** | 0.57 0.94 |

| Patient Global Impression of Change Week 6/Week 24 | 1.68 (1.47 to 1.9) | 0.94 |

| DRUG CLASS | Reduced (or Stopped) | Static | Increased |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paracetamol, n = 6 | 1 (2) | 2 | 1 |

| Anti-inflammatories, n = 4 | 1 (1) | 1 | 1 |

| Opioids, n = 17 | 6 (3) | 6 | 2 |

| Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), n = 11 | 1 (1) | 8 | 1 |

| SSRIs/SNRIs, n = 11 | 0 (2) | 8 | 1 |

| Anticonvulsants, n = 11 | 1 (0) | 9 | 1 |

| Anxiolytics, n = 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Sleeping tablets, n = 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Beta blockers, n = 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Migraine prophylaxis and treatment, n = 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Antipsychotic, n = 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fitzmaurice, B.C.; Heneghan, N.R.; Rayen, A.T.A.; Grenfell, R.L.; Soundy, A.A. Whole-Body Photobiomodulation Therapy for Fibromyalgia: A Feasibility Trial. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 717. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13090717

Fitzmaurice BC, Heneghan NR, Rayen ATA, Grenfell RL, Soundy AA. Whole-Body Photobiomodulation Therapy for Fibromyalgia: A Feasibility Trial. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(9):717. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13090717

Chicago/Turabian StyleFitzmaurice, Bethany C., Nicola R. Heneghan, Asius T. A. Rayen, Rebecca L. Grenfell, and Andrew A. Soundy. 2023. "Whole-Body Photobiomodulation Therapy for Fibromyalgia: A Feasibility Trial" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 9: 717. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13090717

APA StyleFitzmaurice, B. C., Heneghan, N. R., Rayen, A. T. A., Grenfell, R. L., & Soundy, A. A. (2023). Whole-Body Photobiomodulation Therapy for Fibromyalgia: A Feasibility Trial. Behavioral Sciences, 13(9), 717. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13090717