1. Introduction

In a knowledge-based economy, knowledge serves as a critical resource for enterprises to secure a sustainable competitive advantage [

1]. Establishing an environment conducive to knowledge sharing and fostering knowledge creation by urging employees to disseminate their expertise is vital for effective knowledge management [

2]. Given that a substantial portion of an organization’s knowledge resides within individual employees, harnessing this collective expertise and bolstering knowledge exchange among members can significantly augment organizational knowledge stock and innovation capability [

3]. In practical enterprise management, while many organizations implement policies to encourage knowledge sharing internally, there is an observable reluctance among employees to share or, worse, deliberately conceal their knowledge. This tendency can evolve into a counterproductive norm, with evidence suggesting that deliberate knowledge hiding is pervasive [

4]. For instance, a survey found that 46% of respondents would choose not to share knowledge with colleagues upon request [

5]. Another study by AMR indicated that despite substantial investments to foster knowledge sharing, knowledge retention remains prevalent [

6]. Such deliberate withholding, termed “knowledge hiding”, may momentarily benefit the individual but, in the long haul, it could undermine the performance at individual, team, and organizational levels. It is also detrimental to cultivating a knowledge-sharing culture and inhibiting innovation. Hence, addressing knowledge hiding to bolster knowledge sharing is crucial for enhancing enterprises’ technological innovation capabilities, especially in the volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA) environment [

7]. Concurrently, delving into the ramifications of knowledge hiding has enriched associated theoretical discussions, advancing academic insights into knowledge sharing within organizational behavior.

The extant literature on employees’ knowledge-hiding behavior primarily revolves around three central themes: personal factors, organizational and leadership factors, and the characteristics of the knowledge itself. Focusing on personal factors, a body of research has explored the interplay between the Big Five personality traits and knowledge hiding. Studies by Lin and Wang [

8], Anand and Jain [

9], and Wen et al. [

10] found that extraversion, neuroticism, and agreeableness were negatively correlated with knowledge-hiding tendencies. In contrast, conscientiousness and openness were positively associated with such behaviors [

11]. Another study illuminated a pronounced positive correlation between employees’ psychological ownership of knowledge and knowledge hiding [

12]. Furthermore, workplace rejection was shown to enhance knowledge-hiding tendencies. On the organizational and leadership front, research has underscored the negative influence of a conducive organizational knowledge-sharing environment, trust atmosphere, and equity atmosphere on knowledge-hiding tendencies [

13,

14]. Leadership styles also play a pivotal role. For instance, shared leadership [

15] and non-abusive leadership dynamics [

16] act as deterrents to knowledge-hiding behaviors among employees. Turning to the characteristics of knowledge, its complexity, uniqueness, and significance are found to bolster knowledge-hiding tendencies among employees [

17]. Collectively, these comprehensive research findings enrich our comprehension of the intricacies within the knowledge-hiding domain.

Within organizational contexts, workplace envy has emerged as a prevalent emotion among employees. This is primarily attributable to finite resources, propelling incessant competition for opportunities such as promotions, pay hikes, and career advancement [

18,

19]. Rooted in social comparison, workplace envy arises when employees make upward comparisons, leading to painful emotional experiences. Such envy can engender feelings of inferiority, hostility, and resentment, prompting individuals to engage in potentially destructive behaviors in an attempt to bridge perceived disparities [

20]. Despite its significance, the literature offers limited insight into the influence of workplace envy on knowledge-hiding behaviors. Initial studies were primarily concentrated on the detrimental aspects, particularly malicious envy. Research has elucidated that malicious envy can instigate workplace ostracism and curtail employees’ proclivity for self-improvement [

21]. However, recent scholarly endeavors have shed light on a constructive facet of workplace envy, termed “benign envy” [

22,

23]. Although both malicious and benign envy stem from social comparisons, they differ inherently, guiding individuals toward markedly distinct behavioral paths. While malicious envy propels individuals toward actions detrimental to organizational well-being, benign envy acts as a catalyst, motivating individuals to augment organizational performance through heightened dedication [

24]. Yet, the realm of benign envy remains under-explored. Specifically, there is a dearth of studies that delineate the two dimensions of workplace envy and investigate their distinct impacts on knowledge-hiding behaviors.

Social comparison theory posits that in the absence of objective benchmarks, individuals engage in self-evaluative comparisons with others to bolster their self-esteem and self-worth [

25,

26]. Festinger [

24] asserts that social comparison is an intentional act, with individuals typically selecting peers resembling themselves, such as colleagues or classmates, for comparison. The outcomes of these comparisons significantly sway subsequent attitudes and behaviors. Envy emerges as the disconcerting emotion experienced when individuals discern that others possess what they desire [

27]. Recognizing this disparity, individuals might undertake measures to bridge the perceived gap, thereby alleviating their internal dissonance [

28,

29]. This paper proceeds to delve into regulatory focus theory [

30], offering a nuanced examination of how various dimensions of workplace envy influence knowledge-hiding behaviors. Furthermore, this research juxtaposes the effects of workplace envy on knowledge hiding across different generational cohorts. This comparison is pivotal, considering the pronounced divergences in values and behavioral patterns among employees of different age groups, which are shaped by their unique socio-economic experiences [

31].

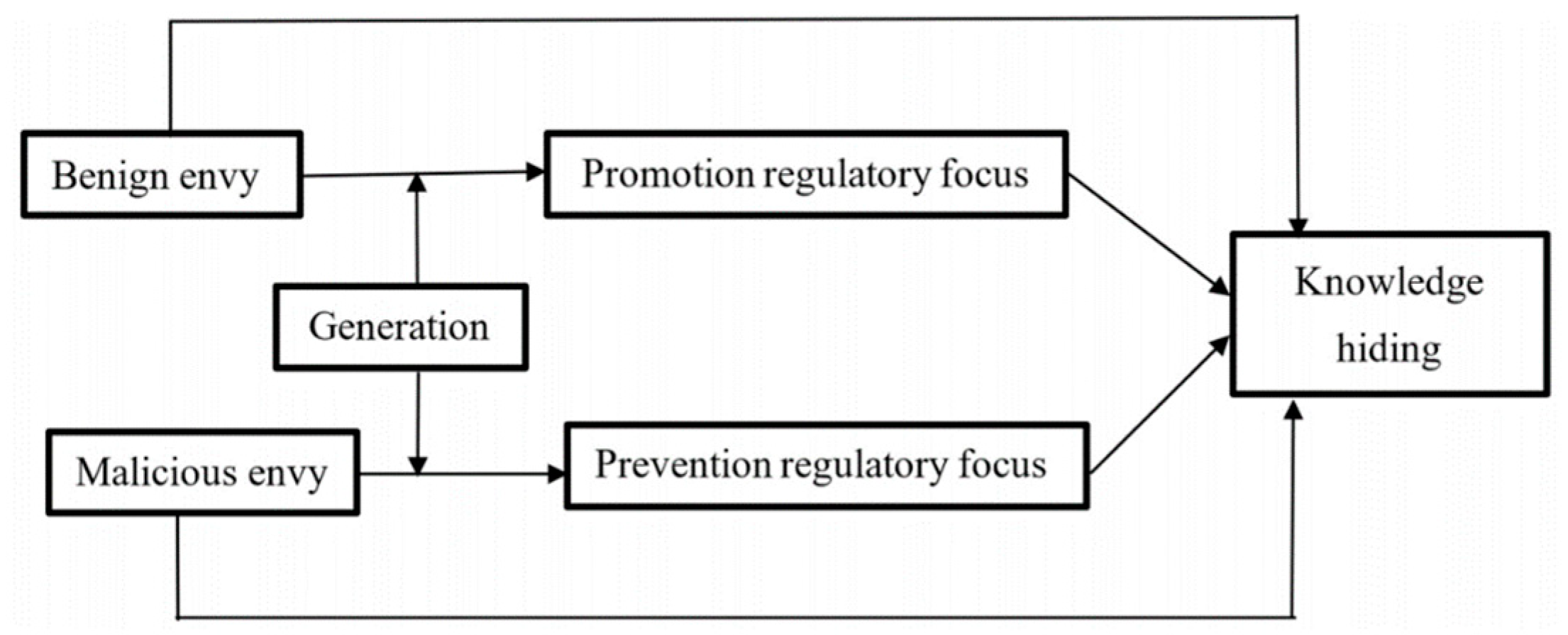

This study delves into the intricate mechanisms underlying the impact of workplace envy on employees’ knowledge-hiding behaviors, drawing from both social comparison theory and regulatory focus theory. We propose a dual-path model that distinguishes the influence of two dimensions of workplace envy: benign envy and malicious envy. This study seeks to elucidate the inner mechanisms of how these dimensions shape knowledge-hiding behaviors and aims to validate the roles of promotion regulatory focus and prevention regulatory focus therein. Furthermore, anchoring our exploration in the generation cohort theory, we investigate intergenerational variations in the effects of workplace envy on knowledge-hiding behavior. This aspect aims to discern the distinct responses of varied generational cohorts in analogous situations. Next, this paper is organized as follows: the second part is the literature review and hypotheses; the third part is the research design, including aspects of sample selection and variable measurement; the fourth part is the analysis of empirical results; and the final part is the research results and discussion.

1.1. Literature Review and Hypotheses

1.1.1. Workplace Envy and Knowledge-Hiding Behavior

Research on workplace envy is predominantly anchored in social comparison theory, which posits that individuals contrast their capabilities and attributes with others to derive a distinct self-evaluation [

11]. Given the inherent competition for limited resources in the workplace, employees invariably engage in comparisons with peers, especially when vying for such scarce resources. Consequently, workplace envy surfaces as an emotional byproduct of these comparisons within a competitive milieu [

32]. Historically, the literature predominantly associated workplace envy with counterproductive employee behaviors, such as hostility and sabotage. However, recent scholarship has acknowledged the duality of envy, bifurcating it into “benign” and “malicious” facets [

33,

34]. For workplace envy, we divide it by whether it will generate hostility toward the comparison object. Benign envy, devoid of hostility, encompasses emotions of desire without animosity toward the envied. It serves as a catalyst, driving individuals to earnestly pursue their aspirations. Conversely, malicious envy—laden with hostility—harbors resentment toward the envied and impels individuals toward actions aimed at diminishing this discomforting emotion. The divergent motivations emanating from these envy types are palpable: benign envy propels employees to relentlessly hone their skills and chase their ambitions, while malicious envy incites detrimental behaviors intended to undermine the comparison target [

35,

36,

37].

Within organizational contexts, the competitive landscape often seeds envy among employees. This envy, born from upward social comparisons, propels individuals to behaviors that mitigate the discomfort associated with such comparisons and bolster a positive self-view. Given that knowledge stands as a pivotal resource enabling employees to accrue organizational power and status, many opt to expand their knowledge base as a tactic to reinforce their stature within the organization. When faced with a colleague’s request for knowledge sharing, maliciously envious employees, driven by resentment, may resort to knowledge hiding. Their aim? To curtail the colleague’s comparative advantage and bridge the perceived competence gap [

25,

38]. Conversely, employees harboring benign envy, while recognizing their positional disparities, align with the spirit of collective advancement. Such employees are predisposed to sharing knowledge, envisaging mutual learning and enhancement as the payoff. Existing literature corroborates these dynamics: malicious envy often fuels exclusionary behaviors aimed at stunting peers’ professional trajectories, whereas benign envy serves as a catalyst, spurring individuals to amplify collaborative endeavors and personal achievements [

39,

40]. As a result, this paper proposes the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1a: Employee benign envy negatively influences knowledge-hiding behavior.

Hypothesis 1b: Employee malicious envy positively influences knowledge-hiding behavior.

1.1.2. The Mediating Effect of the Regulatory Focus

The regulatory focus theory, introduced by Higgins [

41], posits that individuals’ self-regulatory orientations lead them to adopt distinct behaviors and strategies in the pursuit of goals. Broadly, this theory discerns between two primary self-regulatory focuses: promotion and prevention [

42]. Those with a promotional regulatory focus on prioritizing personal growth and development, aiming for positive outcomes. They are oriented toward achieving aspirations and the embodiment of their “ideal self”. Conversely, individuals with a prevention regulatory focus emphasize personal safety and security. Their behaviors typically skew toward avoidance, as they are keen to circumvent negative outcomes or potential losses. They prioritize fulfilling responsibilities and becoming their “ought self”, ensuring they do not deviate from expected roles or norms [

43,

44].

Thus, drawing from the regulatory focus theory, it can be posited that the nature of envy—whether benign or malicious—can activate distinct regulatory focus responses in individuals. Benign envy, being rooted in a positive emotional space, is likely to stimulate the promotion focus in employees. When experiencing benign envy, employees feel inspired by the success or qualities of the comparator and are often motivated to elevate themselves to a similar stature or accomplishment. Such envy serves as a catalyst, driving individuals to aspire, learn, and achieve more, aligning with the characteristics of the promotion focus where individuals seek growth and opportunities. Conversely, malicious envy, stemming from a negative emotional standpoint, can trigger the prevention focus in employees. This form of envy is characterized by resentment toward the comparator and is often paired with a desire to see them lose or face setbacks. Rather than self-improvement, the emotions fuelled by malicious envy incline employees toward defensive actions, safeguarding their current status, or even engaging in behaviors to undercut the comparator. Such responses reflect the essence of the prevention focus, wherein individuals are more cautious, risk-averse, and intent on avoiding adverse outcomes. In light of the above, it becomes evident that the emotional undertone of envy—whether positive (benign) or negative (malicious)—plays a pivotal role in determining the regulatory focus response it elicits in individuals, thereby influencing their consequent behaviors and strategies in the workplace. As a result, the following hypotheses are proposed in this paper.

Hypothesis 2a: Employees’ benign envy has a positive effect on promotion regulatory focus.

Hypothesis 2b: Employees’ malicious envy has a positive effect on prevention regulatory focus.

Promotion regulatory focus pertains to individuals’ growth and development needs. Consequently, employees with this focus aim to achieve their ideal selves, working to bridge the discrepancy between their current and ideal states. When seeking knowledge, such employees are inclined to enhance their skills and understanding through knowledge sharing and communication and are driven by personal growth motivations [

45]. Conversely, prevention regulatory focus emphasizes individuals’ needs for security and stability. Employees under this focus strive to attain their desired selves, seeking to minimize the distance between their current state and this ideal. Within a knowledge-seeking context, those with a prevention regulatory focus are apprehensive about potential losses of power and status and the increasing gap with peers. As a result, they prioritize knowledge protection and security, often displaying knowledge-hiding tendencies and limiting their sharing [

46,

47]. As a result, this paper proposes the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 3a: Promotion regulatory focus reduces employees’ knowledge-hiding behavior.

Hypothesis 3b: Prevention regulatory focus increases employees’ knowledge-hiding behavior.

Integrating Hypothesis 2 and Hypothesis 3 reveals that upward social comparisons among employees, leading to workplace envy, foster two distinct regulatory focus tendencies. These tendencies subsequently influence knowledge-hiding behaviors differently. Specifically, benign envy, characterized as a positive emotion, activates the promotion regulatory focus in employees, reducing knowledge-hiding tendencies. In contrast, malicious envy, rooted in negative emotionality, triggers the prevention regulatory focus, increasing the likelihood of knowledge hiding [

11,

31]. As a result, the following hypotheses are proposed in this paper.

Hypothesis 4a: Promotion regulatory focus plays a mediating effect in the relationship between benign envy and knowledge-hiding behavior.

Hypothesis 4b: Prevention regulatory focus plays a mediating effect in the relationship between malicious envy and knowledge-hiding behavior.

1.1.3. The Moderating Effect of Generation

In recent times, the influx of newer generations such as the post-1980s, post-1990s, and post-2000s into the workforce has accentuated inter-generational diversity. Consequently, the concept of generation cohorts has garnered significant attention in human resource management discourse. Mannheim defines a generation cohort as a group born within the same timeframe and shaped by identical socio-economic, political, and cultural influences [

48]. These cohorts, experiencing pivotal historical events during formative years, develop shared generational identities and consciousness. This shared experience gives rise to common values, cognitive frameworks, and behavioral tendencies. It is also evident that generational groups, molded by varied socio-historical contexts, possess distinct psychological attributes and preferences [

49,

50].

Research on generational classification in Europe and the U.S. primarily delineates four groups: the Traditionalists (born pre-World War II), Baby Boomers (1946–1964), Generation X (1965–1980), and Generation Y (post-1980), the latter often termed the “new generation”. Meanwhile, China’s generational divisions are more varied, with frameworks ranging from two to four generational cohorts [

51,

52,

53]. Using strict birth years as classification criteria oversimplifies distinctions. For instance, employees born in December 1979 and January 1980 have experienced virtually the same societal context, with no significant differences. Based on an extensive review of the literature and the significance of China’s 1992 economic landmark, this study categorizes current working generations into two broad cohorts: the new generation (born post-1992) and the non-new generation (pre-1992). This division stems from China’s pivot toward a market-driven economy in 1992 [

54]. In October 1992, the pivotal 14th Party Congress asserted China’s commitment to a socialist market economy, marking a departure from planning-driven resource allocation. This transition reinvigorated state-owned enterprises, clarifying property rights and responsibilities, and emphasizing the “separation of government and enterprises” and “scientific management”. Consequently, state-owned enterprises gained momentum, and the private sector became instrumental in employment, taxation, and technological innovation. The new generation, molded in this renewed economic landscape, typically boasts better education, coupled with heightened learning aptitude and innovative spirit [

55,

56].

While a wealth of research has explored inter-generational differences in areas such as citizenship behavior, innovation behavior, consumer behavior, and employee well-being [

53,

57], the relationship between workplace envy and knowledge-hiding behavior across different generations remains under-investigated. Much of the prevailing literature leverages Meyer et al.’s [

58] work values framework to discern generational distinctions, focusing on three primary areas: competence and growth, status and independence, and comfort and security. These values, respectively, reflect individuals’ emphasis on learning opportunities and factors like income and promotion and the perceived safety of the work environment. Contrastingly, the new generation, which matured amidst China’s post-reform rapid socio-economic transformation, tends to have a pronounced inclination toward competence and growth. They frequently seek growth via continual learning and communication. On the other hand, the non-new generation (e.g., post-1960s and post-1970s cohorts) was raised during the more materially constrained planned economy, manifesting values centered on income, achievement, and authority. Empirical findings corroborate that the new-generation employees lean more toward competence and growth values, whereas the non-new-generation inclines toward status and independence [

59].

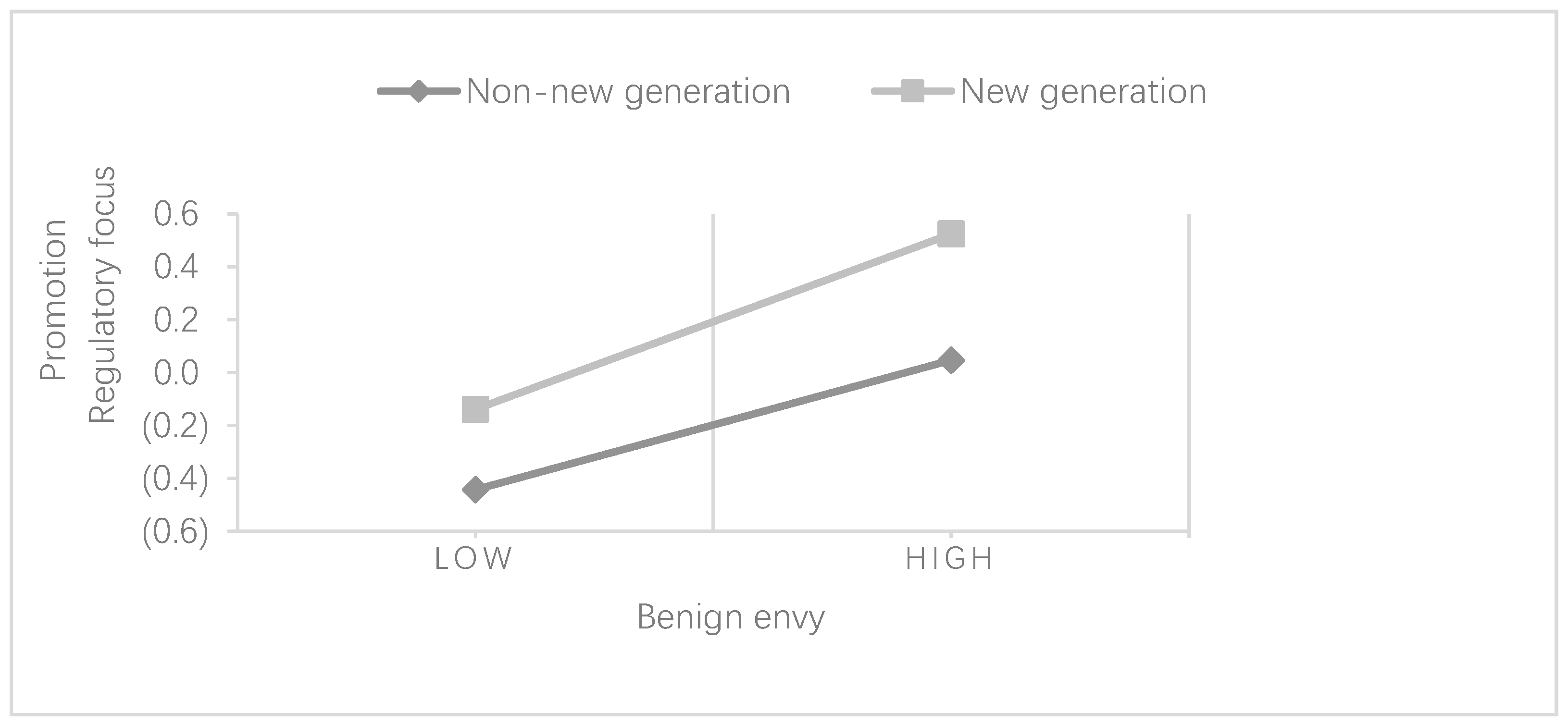

In organizational contexts, generational distinctions might influence how workplace envy affects knowledge hiding, which stems from the varying values of different generational cohorts. While non-new-generation employees often prioritize preserving their existing achievements and status, their newer counterparts emphasize competence and growth in their work value orientation. Consequently, when experiencing benign envy, new-generation employees are likely to manifest a more pronounced promotion regulatory focus. This disposition decreases knowledge-hiding tendencies, fosters knowledge sharing, and bolsters collective competence and knowledge acquisition alongside peers. Conversely, in situations of malicious envy, non-new-generation employees, relative to their newer peers, display a heightened prevention regulatory focus. Such an inclination amplifies knowledge hiding and curtails knowledge sharing. Individuals are motivated by a desire to safeguard their present income and achievements. As a result, this paper proposes the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 5a: “Generation” positively moderated the relationship between benign envy and promotion focus. The younger the employee’s generation, the more pronounced the effect of benign envy on the promotion regulatory focus.

Hypothesis 5b: “Generation” positively moderated the relationship between malicious envy and prevention regulatory focus. The older the employee’s generation, the more pronounced the effect of malicious envy on the prevention regulatory focus.

In summary, the theoretical model proposed in this study is shown in

Figure 1.

4. Research Results

Drawing upon the foundations of social comparison and regulatory focus theories, this study, encompassing a sample of 402 enterprise employees, devises a model to examine the influence of workplace envy on knowledge-hiding behavior. The research aimed to understand the unique impacts of benign and malicious envy on knowledge hiding and discern inter-generational variations in these effects.

First, employees’ benign envy has a significant negative effect on their knowledge-hiding behavior, while malicious envy has a significant positive effect on their knowledge-hiding behavior. That is to say, all the relevant content of Hypothesis 1 can be demonstrated.

Second, the regulatory focus plays a partly mediating effect between workplace envy and knowledge-hiding behavior. Specifically, employees’ benign envy significantly and positively influenced their promotion regulatory focus, which had a negative effect on knowledge-hiding behavior, and the promotion regulatory focus had a partially mediating role between benign envy and knowledge-hiding behavior. Employees’ malicious envy significantly and positively influenced their prevention regulatory focus and the prevention regulatory focus positively influenced knowledge-hiding behavior, and the prevention regulatory focus partially mediated the relationship between malicious envy and knowledge-hiding behavior. That is to say, Hypotheses 2–4 have been demonstrated.

Third, generation has a moderating effect on the relationship between workplace envy and regulatory focus. Specifically, “generation” has a positive moderating effect on the relationship between benign envy and promotion focus; therefore, the younger the employee’s generation, the more pronounced the effect of benign envy on promotion focus. On the other hand, generation has a positive moderating effect on the relationship between malicious envy and prevention regulatory focus; therefore, the older the employee’s generation, the more pronounced the effect of malicious envy on prevention regulatory focus. That is to say, all the relevant content of Hypothesis 5 can be demonstrated.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

First, workplace envy, as an emotional response frequently exhibited by employees during workplace comparisons, differentially influences knowledge-hiding behavior, depending on whether it is benign or malicious. This study pioneers a dual-path model that separately scrutinizes the intrinsic mechanisms through which these two distinct dimensions of envy affect knowledge-hiding behavior. Such a bifurcated examination is notably absent in prior literature. For instance, Peng et al. [

11] probed the nexus between malicious envy and knowledge hiding but overlooked the potential interplay between benign envy and knowledge hiding. Yang and Tang [

64], although they amalgamated both envy types into a unified model to assess individual behaviors, failed to delve into any one relationship with the granularity necessary for comprehensive understanding. Addressing this lacuna, our research bifurcates envy into two dimensions and delves deeply into their respective impacts on knowledge-hiding behavior. We aspire to uncover the underpinnings that bridge envy with knowledge hiding. Through our nuanced exploration of the differential influences of benign and malicious envy on knowledge hiding, we aim to enrich and extend the scholarly discourse on workplace envy.

Second, anchored in the foundations of social comparison and regulatory focus theories, this research delves into the intricate mechanisms through which employees’ workplace envy impacts knowledge-hiding behavior. Specifically, it verifies the mediating roles of both promotion and prevention regulatory focuses in the relationship between workplace envy and knowledge-hiding behavior. While Andiappan and Dufour [

45] found a congruence between malicious envy and prevention regulatory focus and benign envy with promotion regulatory focus, our study embarks on an extended journey. We further decipher the knowledge-hiding behaviors triggered by these regulatory focuses under the aforementioned premise. Our findings reveal that workplace envy among employees does not inherently precipitate knowledge-hiding behaviors. Rather, distinct envy emotions catalyze different regulatory focuses, which in turn can either amplify or mitigate knowledge-hiding behaviors. This nuanced understanding transcends the traditionally linear perspective on the influence of workplace envy on knowledge hiding. Consequently, our research substantially augments the theoretical landscape related to knowledge-hiding behavior.

Third, building upon the framework of generation cohort theory, this study delves into generational distinctions in the way workplace envy influences knowledge-hiding behavior, aiming to unravel how employees from varied generational cohorts respond differently in analogous situations. In alignment with Su et al.’s [

29] categorization approach for dissecting employee values, our research adopts 1992 as a demarcation point to differentiate between the “new generation” and the non-new generation, a method that resonates with contemporary Chinese generational research. From our bifurcated sample, it became evident that younger employee cohorts exhibited a more pronounced influence of benign envy on promotion regulatory focus. Conversely, older cohorts displayed a heightened effect of malicious envy on prevention regulatory focus. This exploration into generational nuances in relation to workplace envy’s influence on knowledge-hiding behavior significantly enriches the understanding of how generational cohort attributes intersect with employee work behavior.

5.2. Practical Significance

The research in this paper is of great relevance and includes three main aspects. First, knowledge hiding might offer fleeting advantages to individual employees, but its repercussions stifle the collective growth and innovative spirit of teams and organizations. It is incumbent upon organizations to not only promote but also incentivize knowledge sharing. By reinforcing organizational learning and robust knowledge management systems, an atmosphere conducive to open exchange can be nurtured. Even though knowledge sharing might seem above and beyond an employee’s designated role, its centrality in driving knowledge creation warrants the provision of apt rewards. Such tangible acknowledgments can serve as a potent deterrent against the inclination to hoard knowledge.

Second, envy in the workplace, be it benign or malicious, wields influence over employees’ knowledge-sharing tendencies. Recognizing this, it is crucial for organizational leaders to discern between these two facets of envy. Addressing them requires a dual strategy. Firstly, there is a need to channel malicious envy into its benign counterpart, mitigating its adverse impacts on work dynamics. Simultaneously, fostering an environment that supports and nurtures the aspirations of those with benign envy becomes imperative. Such an atmosphere not only satisfies their growth aspirations but also propels them to excel in their roles.

Third, diverse generational perspectives influence workplace behaviors, particularly around envy and knowledge sharing. With older cohorts or non-new-generation employees exhibiting tendencies to safeguard knowledge to uphold their stature, organizations face a unique challenge. Navigating this intricacy means that organizational strategies should prioritize these employees, cultivating an environment that encourages and rewards open knowledge dissemination.

5.3. Research Limitations

There are some limitations in the research process of this paper.

First, while the survey primarily relied on cross-sectional data, we collected data in two separate phases. However, these collection points were closely spaced. The variables, notably workplace envy and knowledge hiding, are sensitive in nature and may be susceptible to biases, particularly if participants’ emotions influenced their responses. Recognizing these potential limitations, future research could adopt a longitudinal approach, perhaps utilizing a diary study method, or incorporate additional experimental designs for more robust hypothesis testing, aiming to capture data that more accurately reflects reality.

Second, most of the study’s participants were from South China, although the research hypotheses were extensively tested. To enhance the generalizability of the results, future research should consider diversifying the geographical distribution of the sample.

Third, in this study, generational cohorts were categorized as “new generation” and “non-new generation” based on the division using the year 1992 as the demarcation point. It is noteworthy that existing literature on generational studies offers a variety of methods for dividing generational populations. In forthcoming research, alternative divisions could be considered, such as distinguishing cohorts into three or more generations or employing different temporal markers to enhance the depth and scope of relevant investigations.