Adolescent Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Interplay of Age, Gender, and Mental Health Outcomes in Two Consecutive Cross-Sectional Surveys in Northern Italy

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Age and gender have been identified as significant predictors for elevated cumulative scores for symptoms of generalized anxiety, depression, and psychosomatic complaints, as well as lower cumulative scores for health-related quality of life. These four scores can be categorized into normal and symptomatic cases. The aim was to explore whether the percentage of participants classified as symptomatic varied significantly by age and gender. This question was examined across four dichotomous outcome variables: symptoms of anxiety, depressive symptoms, at least three psychosomatic complaints per week, and low health-related quality of life.

- Is it feasible to infer one outcome variable from another? In other words, does any symptomatic variable serve as a predictor for other symptoms?

- Can adolescents with “lowered family climate due to the pandemic”, “difficult social factors not related to the pandemic”, or “increased burden due to the pandemic” be identified as vulnerable groups at a significantly higher risk for any of the four outcome parameters?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Framework and Participants

2.2. Assessment Tools

2.2.1. Sociodemographic Information and COVID-19 Impact

2.2.2. HRQoL and Mental Health

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics and Pandemic-Related Variables

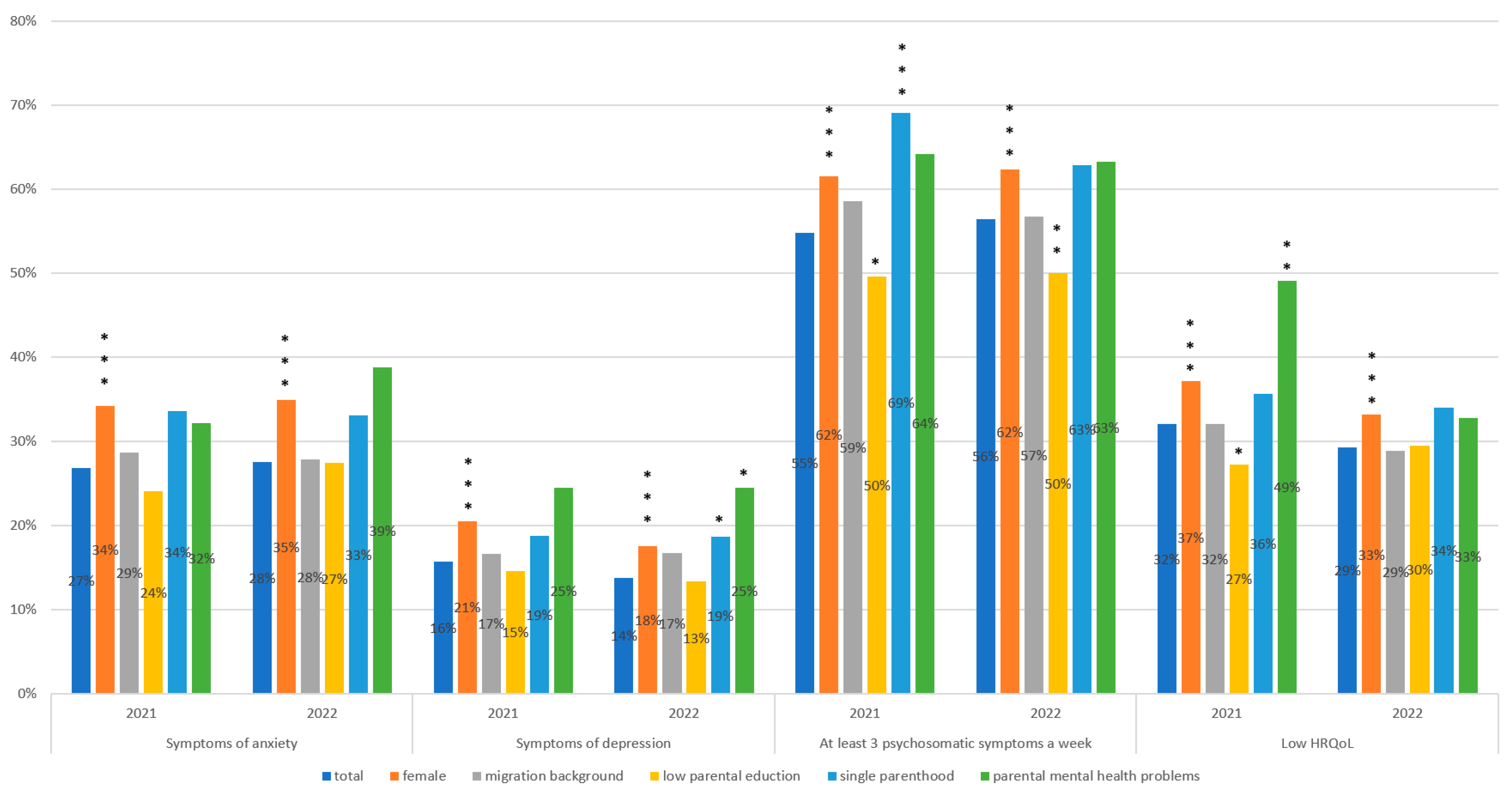

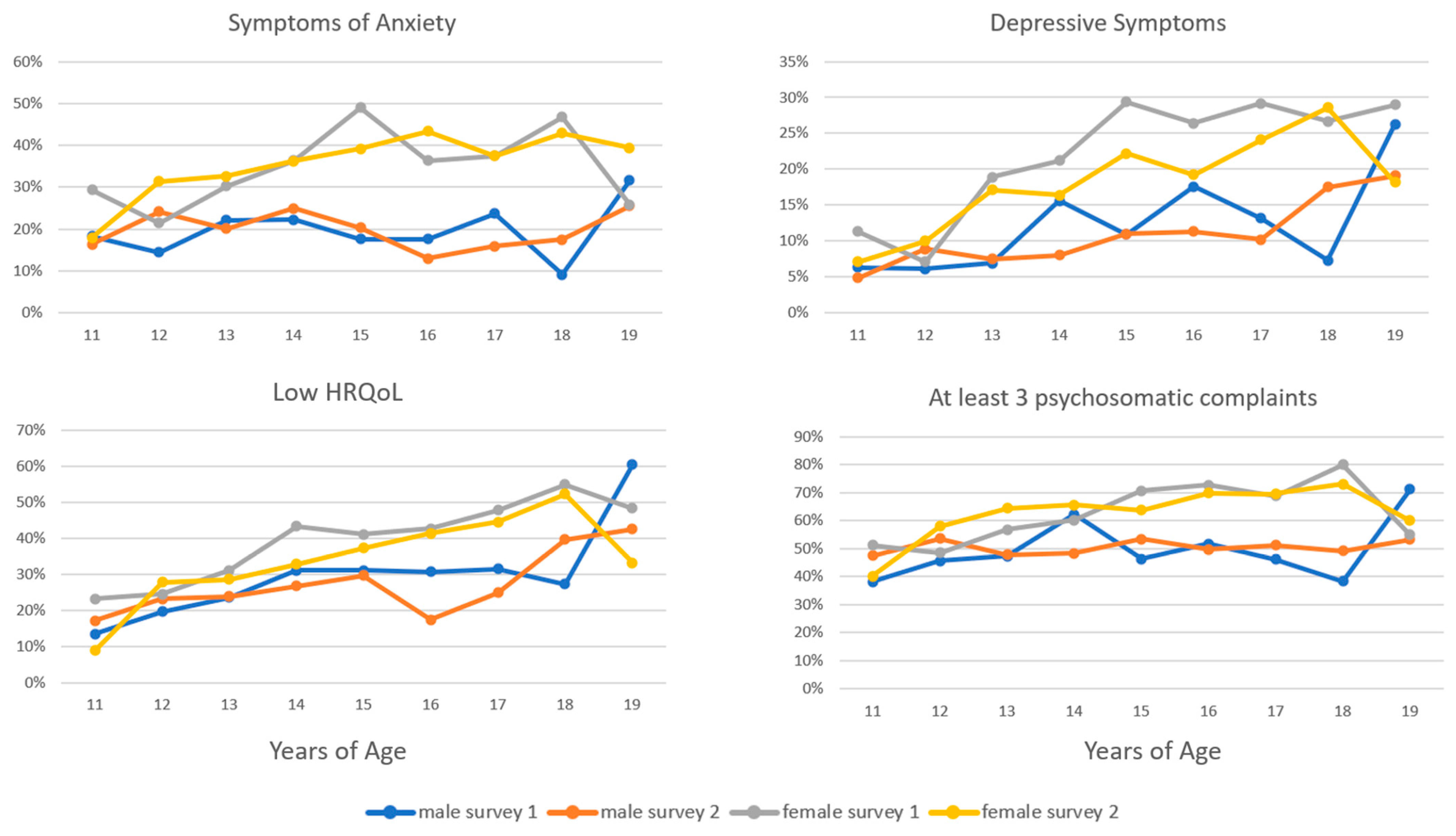

3.2. Age- and Gender-Specific HRQoL and Mental Health Outcomes

3.3. Self-Versus Proxy-Reported HRQoL and Psychosomatic Complaints

3.4. Sensitivities, Specificities, and Correlations between HRQoL and Mental Health Outcomes

3.5. Construction of the Logistic Regression Model: Incorporating Pandemic-Related Factors and Health Outcomes

3.5.1. Predictors for the Model

3.5.2. Logistic Regression Models for Dichotomous Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Harrison, L.; Carducci, B.; Klein, J.D.; Bhutta, Z.A. Indirect Effects of COVID-19 on Child and Adolescent Mental Health: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e010713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, C.; Deutsch, N.; Cuadros, O.; Franco, E.; Rojas, M.; Roux, G.; Sánchez, F. Adolescent Peer Processes in Extracurricular Activities: Identifying Developmental Opportunities. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 118, 105457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, N. Participation in Extracurricular Activities and Adolescent Adjustment: Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Findings. J. Youth Adolesc. 2005, 34, 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eder, D.; Nenga, S.K. Socialization in Adolescence. In Handbook of Social Psychology; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 157–182. [Google Scholar]

- Von Soest, T.; Bakken, A.; Pedersen, W.; Sletten, M.A. Life Satisfaction among Adolescents before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Tidsskr. Nor. Laegeforen. 2020, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branje, S.; Morris, A.S. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Adolescent Emotional, Social, and Academic Adjustment. J. Res. Adolesc. 2021, 31, 486–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magson, N.R.; Freeman, J.Y.; Rapee, R.M.; Richardson, C.E.; Oar, E.L.; Fardouly, J. Risk and Protective Factors for Prospective Changes in Adolescent Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, B.; Biswas, U.N.; Mansukhani, R.T.; Casarín, A.V.; Essau, C.A. The Impact of COVID-19 Lockdown on Internet Use and Escapism in Adolescents. Rev. Psicol. Clín.a Niños Adolesc. 2020, 7, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawes, M.T.; Szenczy, A.K.; Klein, D.N.; Hajcak, G.; Nelson, B.D. Increases in Depression and Anxiety Symptoms in Adolescents and Young Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychol. Med. 2022, 52, 3222–3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacco, D. Loneliness and Mood Disorders: Consequence, Cause and/or Unholy Alliance? Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2023, 36, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velez, G.; Hahn, M.; Troyer, B. Making Meaning of COVID-19: An Exploratory Analysis of US Adolescent Experiences of the Pandemic. Transl. Issues Psychol. Sci. 2022, 8, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benninger, E.; Schmidt-Sane, M.; Hajski, A. Youth Lens: Youth Perspectives on the COVID-19 Pandemic and its Impact on Well-being in an Urban Community. Int. J. Child Malt. 2022, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patton, G.C.; Sawyer, S.M.; Santelli, J.S.; Ross, D.A.; Afifi, R.; Allen, N.B.; Arora, M.; Azzopardi, P.; Baldwin, W.; Bonell, C.; et al. Our Future: A Lancet Commission on Adolescent Health and Wellbeing. Lancet 2016, 387, 2423–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, R.M.; Foch, T.T. (Eds.) Biological-Psychosocial Interactions in Early Adolescence; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; ISBN 978-1-00-321799-2. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging Adulthood: A Theory of Development from the Late Teens through the Twenties. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barzeva, S.A.; Richards, J.S.; Veenstra, R.; Meeus, W.H.; Oldehinkel, A.J. Quality over Quantity: A Transactional Model of Social Withdrawal and Friendship Development in Late Adolescence. Soc. Dev. 2022, 31, 126–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skinner, A.T.; Çiftçi, L.; Jones, S.; Klotz, E.; Ondrušková, T.; Lansford, J.E.; Alampay, L.P.; Al-Hassan, S.M.; Bacchini, D.; Bornstein, M.H. Adolescent Positivity and Future Orientation, Parental Psychological Control, and Young Adult Internalising Behaviours during COVID-19 in Nine Countries. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinlay, A.R.; May, T.; Dawes, J.; Fancourt, D.; Burton, A. ‘You’Re Just There, Alone in Your Room with Your Thoughts’: A Qualitative Study about the Psychosocial Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic among Young People Living in the UK. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e053676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockyer, B.; Endacott, C.; Dickerson, J.; Sheard, L. Growing up during a Public Health Crisis: A Qualitative Study of Born in Bradford Early Adolescents during COVID-19. BMC Psychol. 2022, 10, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garagiola, E.R.; Lam, Q.; Wachsmuth, L.S.; Tan, T.Y.; Ghali, S.; Asafo, S.; Swarna, M. Adolescent Resilience during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review of the Impact of the Pandemic on Developmental Milestones. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Torsheim, T.; Hetland, J.; Vollebergh, W.; Cavallo, F.; Jericek, H.; Alikasifoglu, M.; Välimaa, R.; Ottova, V.; Erhart, M.; et al. Subjective Health, Symptom Load and Quality of Life of Children and Adolescents in Europe. Int. J. Public Health 2009, 54 (Suppl. 2), 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demkowicz, O.; Ashworth, E.; O’Neill, A.; Hanley, T.; Pert, K. “Will My Young Adult Years be Spent Socially Distancing?”: A Qualitative Exploration of Adolescents’ Experiences During the COVID-19 UK Lockdown. J. Adolesc. Res. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Kaman, A.; Erhart, M.; Devine, J.; Schlack, R.; Otto, C. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Quality of Life and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents in Germany. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 31, 879–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Kaman, A.; Erhart, M.; Otto, C.; Devine, J.; Löffler, C.; Hurrelmann, K.; Bullinger, M.; Barkmann, C.; Siegel, N.A.; et al. Quality of Life and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents during the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Results of a Two-Wave Nationwide Population-Based Study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2023, 32, 575–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Erhart, M.; Devine, J.; Gilbert, M.; Reiss, F.; Barkmann, C.; Siegel, N.; Simon, A.; Hurrelmann, K.; Schlack, R.; et al. Child and Adolescent Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Results of the Three-Wave Longitudinal COPSY Study; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Meda, N.; Pardini, S.; Slongo, I.; Bodini, L.; Zordan, M.A.; Rigobello, P.; Visioli, F.; Novara, C. Students’ Mental Health Problems before, during, and after COVID-19 Lockdown in Italy. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 134, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melegari, M.G.; Giallonardo, M.; Sacco, R.; Marcucci, L.; Orecchio, S.; Bruni, O. Identifying the Impact of the Confinement of Covid-19 on Emotional-Mood and Behavioural Dimensions in Children and Adolescents with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Psychiatry Res. 2021, 296, 113692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, V.; Wiedermann, C.J.; Kaman, A.; Erhart, M.; Piccoliori, G.; Plagg, B.; Mahlknecht, A.; Ausserhofer, D.; Engl, A.; Ravens-Sieberer, U. Quality of Life and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents after the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Large Population-Based Survey in South Tyrol, Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, V.; Wiedermann, C.J.; Piccoliori, G.; Mahlknecht, A.; Plagg, B.; Ausserhofer, D.; Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Engl, A. Evolution of Youth’s Mental Health and Quality of Life during the COVID-19 Pandemic in South Tyrol, Italy: Comparison of Two Representative Surveys. Children 2023, 10, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loades, M.E.; Chatburn, E.; Higson-Sweeney, N.; Reynolds, S.; Shafran, R.; Brigden, A.; Linney, C.; McManus, M.N.; Borwick, C.; Crawley, E. Rapid Systematic Review: The Impact of Social Isolation and Loneliness on the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents in the Context of COVID-19. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 59, 1218–1239.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breaux, R.; Dvorsky, M.R.; Marsh, N.P.; Green, C.D.; Cash, A.R.; Shroff, D.M.; Buchen, N.; Langberg, J.M.; Becker, S.P. Prospective Impact of COVID-19 on Mental Health Functioning in Adolescents with and without ADHD: Protective Role of Emotion Regulation Abilities. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2021, 62, 1132–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Justice Canada. Policy on Gender-Based Analysis Plus: Applying an Intersectional Approach to Foster Inclusion and Address Inequities. Available online: https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/abt-apd/pgbap-pacsp.html (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- König, W.; Lüttinger, P.; Müller, W. A Comparative Analysis of the Development and Structure of Educational Systems: Methodological Foundations and the Construction of a Comparative Educational Scale; Institut für Sozialwissenschaften, Universität Mannheim: Mannheim, Germany, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Brauns, H.; Scherer, S.; Steinmann, S. The CASMIN Educational Classification in International Comparative Research. In Advances in Cross-National Comparison: A European Working Book for Demographic and Socio-Economic Variables; Hoffmeyer-Zlotnik, J.H.P., Wolf, C., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 221–244. ISBN 978-1-4419-9186-7. [Google Scholar]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Herdman, M.; Devine, J.; Otto, C.; Bullinger, M.; Rose, M.; Klasen, F. The European KIDSCREEN Approach to Measure Quality of Life and Well-Being in Children: Development, Current Application, and Future Advances. Qual. Life Res. 2014, 23, 791–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birmaher, B.; Brent, D.A.; Chiappetta, L.; Bridge, J.; Monga, S.; Baugher, M. Psychometric Properties of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): A Replication Study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1999, 38, 1230–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitkamp, K.; Romer, G.; Rosenthal, S.; Wiegand-Grefe, S.; Daniels, J. German Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): Reliability, Validity, and Cross-Informant Agreement in a Clinical Sample. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2010, 4, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocetti, E.; Hale, W.W.; Fermani, A.; Raaijmakers, Q.; Meeus, W. Psychometric Properties of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED) in the General Italian Adolescent Population: A Validation and a Comparison between Italy and The Netherlands. J. Anxiety Disord. 2009, 23, 824–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Haugland, S.; Wold, B.; Stevenson, J.; Aaroe, L.E.; Woynarowska, B. Subjective Health Complaints in Adolescence. A Cross-National Comparison of Prevalence and Dimensionality. Eur. J. Public Health 2001, 11, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: Validity of a Two-Item Depression Screener. Med. Care 2003, 41, 1284–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, M.; Strohmayer, M.; Mühlig, S.; Schwaighofer, B.; Wittmann, M.; Faller, H.; Schultz, K. Assessment of Depression before and after Inpatient Rehabilitation in COPD Patients: Psychometric Properties of the German Version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9/PHQ-2). J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 232, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Argenio, P.; Minardi, V.; Mirante, N.; Mancini, C.; Cofini, V.; Carbonelli, A.; Diodati, G.; Granchelli, C.; Trinito, M.O.; Tarolla, E. Confronto Tra Due Test per La Sorveglianza Dei Sintomi Depressivi Nella Popolazione. Not. Ist. Super. Sanità 2013, 26, i–iii. [Google Scholar]

- Nyberg, G.; Helgadóttir, B.; Kjellenberg, K.; Ekblom, Ö. COVID-19 and Unfavorable Changes in Mental Health Unrelated to Changes in Physical Activity, Sedentary Time, and Health Behaviors among Swedish Adolescents: A Longitudinal Study. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1115789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, G.; Cohen, Z.P.; Paulus, M.P.; Tsuchiyagaito, A.; Kirlic, N. Sustained Increase in Depression and Anxiety among Psychiatrically Healthy Adolescents during Late Stage COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1137842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorisdottir, I.E.; Agustsson, G.; Oskarsdottir, S.Y.; Kristjansson, A.L.; Asgeirsdottir, B.B.; Sigfusdottir, I.D.; Valdimarsdottir, H.B.; Allegrante, J.P.; Halldorsdottir, T. Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Adolescent Mental Health and Substance Use up to March, 2022, in Iceland: A Repeated, Cross-Sectional, Population-Based Study. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2023, 7, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Devine, J.; Napp, A.-K.; Kaman, A.; Saftig, L.; Gilbert, M.; Reiß, F.; Löffler, C.; Simon, A.M.; Hurrelmann, K.; et al. Three Years into the Pandemic: Results of the Longitudinal German COPSY Study on Youth Mental Health and Health-Related Quality of Life. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1129073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, N.; Kadowaki, T.; Takanaga, S.; Shigeyasu, Y.; Okada, A.; Yorifuji, T. Longitudinal Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Development of Mental Disorders in Preadolescents and Adolescents. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newlove-Delgado, T.; Russell, A.E.; Mathews, F.; Cross, L.; Bryant, E.; Gudka, R.; Ukoumunne, O.C.; Ford, T.J. Annual Research Review: The Impact of Covid-19 on Psychopathology in Children and Young People Worldwide: Systematic Review of Studies with Pre- and within-Pandemic Data. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2022, 64, 611–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viner, R.; Russell, S.; Saulle, R.; Croker, H.; Stansfield, C.; Packer, J.; Nicholls, D.; Goddings, A.-L.; Bonell, C.; Hudson, L.; et al. School Closures During Social Lockdown and Mental Health, Health Behaviors, and Well-Being Among Children and Adolescents During the First COVID-19 Wave: A Systematic Review. JAMA Pediatr. 2022, 176, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, J.; Zhou, F.; Hou, W.; Heybati, K.; Lohit, S.; Abbas, U.; Silver, Z.; Wong, C.Y.; Chang, O.; Huang, E.; et al. Prevalence of Mental Health Symptoms in Children and Adolescents during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Meta-Analysis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2023, 1520, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussières, E.-L.; Malboeuf-Hurtubise, C.; Meilleur, A.; Mastine, T.; Hérault, E.; Chadi, N.; Montreuil, M.; Généreux, M.; Camden, C. Consequences of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children’s Mental Health: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 691659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, J.; Xu, H.; An, N.; Zhang, P.; Liu, F.; He, S.; Hu, N.; Xiao, X.; Cui, Y.; Li, Y. The Prevalence of Mental Problems for Chinese Children and Adolescents During COVID-19 in China: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 661796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elharake, J.A.; Akbar, F.; Malik, A.A.; Gilliam, W.; Omer, S.B. Mental Health Impact of COVID-19 among Children and College Students: A Systematic Review. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2023, 54, 913–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.M.; Nesa, F.; Das, J.; Aggad, R.; Tasnim, S.; Bairwa, M.; Ma, P.; Ramirez, G. Global Burden of Mental Health Problems among Children and Adolescents during COVID-19 Pandemic: An Umbrella Review. Psychiatry Res. 2022, 317, 114814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Listernick, Z.I.; Badawy, S.M. Mental Health Implications of the COVID-19 Pandemic Among Children and Adolescents: What Do We Know so Far? Pediatr. Health Med. Ther. 2021, 12, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig-Walz, H.; Dannheim, I.; Pfadenhauer, L.M.; Fegert, J.M.; Bujard, M. Increase of Depression among Children and Adolescents after the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Europe: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2022, 16, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meade, J. Mental Health Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children and Adolescents: A Review of the Current Research. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 68, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, C.S.M.; Ng, S.S.L. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children’s Mental Health: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 975936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, J.M.D.; Butini, L.; Pauletto, P.; Lehmkuhl, K.M.; Stefani, C.M.; Bolan, M.; Guerra, E.; Dick, B.; De Luca Canto, G.; Massignan, C. Mental Health Effects Prevalence in Children and Adolescents during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Worldviews Evid.-Based Nurs. 2022, 19, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oostrom, T.G.; Cullen, P.; Peters, S.A. The Indirect Health Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children and Adolescents: A Review. J. Child Health Care 2022, 13674935211059980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saulle, R.; De Sario, M.; Bena, A.; Capra, P.; Culasso, M.; Davoli, M.; De Lorenzo, A.; Lattke, L.S.; Marra, M.; Mitrova, Z.; et al. School Closures and Mental Health, Wellbeing and Health Behaviours among Children and Adolescents during the Second COVID-19 Wave: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Epidemiol. Prev. 2022, 46, 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śniadach, J.; Szymkowiak, S.; Osip, P.; Waszkiewicz, N. Increased Depression and Anxiety Disorders during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Children and Adolescents: A Literature Review. Life 2021, 11, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theberath, M.; Bauer, D.; Chen, W.; Salinas, M.; Mohabbat, A.B.; Yang, J.; Chon, T.Y.; Bauer, B.A.; Wahner-Roedler, D.L. Effects of COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Survey Studies. SAGE Open Med. 2022, 10, 20503121221086710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Chen, L.; Ran, H.; Che, Y.; Fang, D.; Sun, H.; Peng, J.; Liang, X.; Xiao, Y. Depression and Anxiety among Children and Adolescents Pre and Post COVID-19: A Comparative Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 917552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amicucci, G.; Salfi, F.; D’Atri, A.; Viselli, L.; Ferrara, M. The Differential Impact of COVID-19 Lockdown on Sleep Quality, Insomnia, Depression, Stress, and Anxiety among Late Adolescents and Elderly in Italy. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdzovic Andreas, J.; Brunborg, G.S. Self-Reported Mental and Physical Health Among Norwegian Adolescents Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2121934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, S.E.; Best, J.; Selles, R.; Naqqash, Z.; Lin, B.; Lu, C.; Au, A.; Snell, G.; Westwell-Roper, C.; Vallani, T.; et al. Age-Specific Determinants of Psychiatric Outcomes after the First COVID-19 Wave: Baseline Findings from a Canadian Online Cohort Study. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2023, 17, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanfredi, M.; Dagani, J.; Geviti, A.; Di Cosimo, F.; Bussolati, M.; Rillosi, L.; Albini, D.; Pizzi, M.; Ghidoni, R.; Fazzi, E.; et al. Risk and Protective Factors Associated with Mental Health Status in an Italian Sample of Students during the Fourth Wave of COVID-19 Pandemic. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2023, 17, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brites, R.; Paulino, M.; Brissos, S.; Gabriel, S.; Alho, L.; Simões, M.R.; Silva, C.F. Initial Psychological Reactions to COVID-19 of Middle Adolescents in Portugal. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witteveen, A.B.; Young, S.Y.; Cuijpers, P.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Barbui, C.; Bertolini, F.; Cabello, M.; Cadorin, C.; Downes, N.; Franzoi, D.; et al. COVID-19 and Common Mental Health Symptoms in the Early Phase of the Pandemic: An Umbrella Review of the Evidence. PLoS Med. 2023, 20, e1004206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, K.; Schmitz, J. Scoping review: Longitudinal effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on child and adolescent mental health. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2023, 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geweniger, A.; Haddad, A.; Barth, M.; Högl, H.; Mund, A.; Insan, S.; Langer, T. Mental Health of Children with and without Special Healthcare Needs and of Their Caregivers during COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2022, 6, e001509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenter, A.; Schickl, M.; Sevecke, K.; Juen, B.; Exenberger, S. Children’s Mental Health During the First Two Years of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Burden, Risk Factors and Posttraumatic Growth—A Mixed-Methods Parents’ Perspective. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 901205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevecke, K.; Wenter, A.; Haid-Stecher, N.; Fuchs, M.; Böge, I. A three-country comparison of mental health and treatment options of children and adolescents with mental health problems in times after the COVID-19 pandemic. Neuropsychiatrie 2022, 36, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.J.; Barblan, L.P.; Lory, I.; Landolt, M.A. Age-Related Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health of Children and Adolescents. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2021, 12, 1901407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babore, A.; Trumello, C.; Lombardi, L.; Candelori, C.; Chirumbolo, A.; Cattelino, E.; Baiocco, R.; Bramanti, S.M.; Viceconti, M.L.; Pignataro, S.; et al. Mothers’ and Children’s Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown: The Mediating Role of Parenting Stress. Child. Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2023, 54, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Z.; Mazzeschi, C.; Delvecchio, E. The Impact of Parental Stress on Italian Adolescents’ Internalizing Symptoms during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Longitudinal Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total † | ||

|---|---|---|

| 2021 (n = 1760) | 2022 (n = 1885) | |

| Sociodemographic | M (SD) | M (SD) |

| Age | 14.22 (2.34) | 14.40 (2.31) |

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Female | 903 (51.3) | 975 (51.7) |

| Migration background ‡ | 181 (11.1) | 179 (10.3) |

| Low parental education ‡ | 419 (24.8) | 391 (21.5) |

| Single parenthood ‡ | 149 (8.6) | 188 (10.0) |

| Parental mental health problem ‡ | 53 (3.0) | 49 (2.6) |

| Pandemic-related | ||

| Extended parental workload ‡,§ | 605 (38.1) | 619 (35.6) |

| General burden | 528 (30.2) | 22.9 (9.58) |

| Lower family climate | 464 (26.5) | 348 (18.5) |

| Elevated burden at school | 1151 (65.5) | 1087 (57.9) |

| Less contact with friends | 1067 (60.7) | 720 (38.2) |

| Extended use of digital media | 1214 (69.1) | 1049 (55.9) |

| Gender | COP-S Survey | n | Low HRQoL † | At least 3 Psychosomatic Complaints a Week † | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Reported | Proxy-Reported | p-Value ‡ | Self-Reported | Proxy-Reported | p-Value ‡ | |||

| Boys | 2021 | 858 | 229 (26.7) | 244 (29.0) | n.s. | 411 (47.9) | 377 (44.8) | n.s. |

| 2022 | 911 | 231 (25.4) | 208 (23.3) | n.s. | 457 (50.2) | 395 (44.3) | <0.001 | |

| p-value § | n.s. | 0.008 | n.s. | n.s. | ||||

| Girls | 2021 | 903 | 335 (37.1) | 280 (31.6) | <0.001 | 555 (61.5) | 465 (52.7) | <0.001 |

| 2022 | 975 | 323 (33.1) | 228 (23.9) | <0.001 | 607 (62.3) | 511 (53.7) | <0.001 | |

| p-value § | n.s. | <0.001 | n.s. | n.s. | ||||

| Gender | COP-S Year | Outcome to Detect | When Having Other Outcome | Kendall Tau-b Correlation Coefficient | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Specificity | ||||

| Boys | 2021 | Anxiety | 54.35 [43.63; 64.78] | 85.25 [82.54; 87.69] | 0.312 *** |

| Depression | 30.67 [23.70; 38.37] | 93.96 [91.92; 95.61] | |||

| 2022 | Anxiety | 52.22 [41.43; 62.87] | 84.04 [81.36; 86.48] | 0.273 *** | |

| Depression | 26.40 [20.09; 33.52] | 94.13 [92.18; 95.72] | |||

| Girls | 2021 | Anxiety | 69.73 [62.56; 76.25] | 74.93 [71.59; 78.06] | 0.380 *** |

| Depression | 41.75 [36.19; 47.47] | 90.57 [87.93; 92.80] | |||

| 2022 | Anxiety | 79.53 [72.70; 85.31] | 74.63 [71.47; 77.60] | 0.432 *** | |

| Depression | 40,00 [34.75; 45.42] | 94.49 [92.42; 96.13] | |||

| Boys | 2021 | Anxiety | 43.23 [36.72; 49.92] | 89.83 [87.19; 92.08] | 0.373 *** |

| HRQoL | 60.74 [52.79; 68.28] | 81.29 [78.19; 84.13] | |||

| 2022 | Anxiety | 46.75 [40.18; 53.41] | 89.71 [87.17; 91.89] | 0.400 *** | |

| HRQoL | 60.67 [53.09; 67.90] | 83.22 [80.31; 85.86] | |||

| Girls | 2021 | Anxiety | 58.51 [53.03; 63.84] | 80.11 [76.58; 83.31] | 0.393 *** |

| HRQoL | 63.43 [57.57; 68.09] | 76.60 [72.98; 79.95] | |||

| 2022 | Anxiety | 66.06 [60.64; 71.17] | 80.66 [77.45; 83.61] | 0.463 *** | |

| HRQoL | 62.94 [57.57; 68.09] | 82.83 [79.67; 85.69] | |||

| Boys | 2021 | Anxiety | 32.36 [27.86; 37.12] | 93.29 [90.56; 95.43] | 0.327 *** |

| Psychosom | 81.6 [74.78; 87.22] | 60 [56.25; 63.66] | |||

| 2022 | Anxiety | 30.84 [26.65; 35.31] | 91.85 [88.94; 94.20] | 0.286 *** | |

| Psychosom | 79.21 [72.51; 84.92] | 56.89 [53.21; 60.51] | |||

| Girls | 2021 | Anxiety | 49.19 [44.95; 53.43] | 88.35 [84.24; 91.71] | 0.398 *** |

| Psychosom. | 88.35 [84.24; 91.71] | 52.53 [48.42; 56.60] | |||

| 2022 | Anxiety | 50.16 [46.15; 54.18] | 90.84 [87.43; 93.57] | 0.419 ** | |

| Psychosom | 90.76 [87.33; 93.52] | 63.60 [60.22; 66.89] | |||

| Boys | 2021 | Depression | 32.61 [26.59; 39.08] | 97.16 [95.54; 98.31] | 0.421 *** |

| HRQoL | 80.43 [70.85; 87.97] | 79.77 [76.74; 82.56] | |||

| 2022 | Depression | 30.74 [24.85; 37.12] | 97.24 [95.72; 98.33] | 0.407 *** | |

| HRQoL | 78.89 [69.01; 86.79] | 80.51 [77.63; 83.17] | |||

| Girls | 2021 | Depression | 46.59 [41.16, 52.07] | 95.10 [93.00; 96.72] | 0.502 *** |

| HRQoL | 84.86 [78.87; 89.70] | 75.21 [71.88; 78.33] | |||

| 2022 | Depression | 44.95 [39.48; 50.52] | 95.92 [94.12; 97.30] | 0.506 *** | |

| HRQoL | 84.80 [78.52; 89.82] | 77.86 [74.83, 80.69] | |||

| Boys | 2021 | Depression | 18.45 [14.82; 22.54] | 96.23 [94.03; 97.79] | 0.223 *** |

| Psychosom | 81.52 [72.07; 88.85] | 56.14 [52.54; 59.69] | |||

| 2022 | Depression | 17.38 [14.05; 21.33] | 97.62 [95.78; 98.81] | 0.264 *** | |

| Psychosom | 90.00 [81.86; 95.32] | 54.20 [50.72; 57.65] | |||

| Girls | 2021 | Depression | 31.13 [27.31; 35.15] | 96.86 [94.45; 98.42] | 0.340 *** |

| Psychosom | 94.05 [89.12; 96.99] | 46.94 [43.23; 50.66] | |||

| 2022 | Depression | 27.51 [24.02; 31.21] | 98.92 [97.26; 99.71] | 0.337 *** | |

| Psychosom. | 97.66 [94.12; 99.36] | 45.27 [41.79; 48.79] | |||

| Boys | 2021 | HRQoL | 45.26 [40.37; 50.21] | 90.38 [87.26; 92.95] | 0.402 *** |

| Psychosom | 81.22 [75.55; 86.06] | 64.23 [60.34; 67.98] | |||

| 2022 | HRQoL | 42.01 [37.44; 46.69] | 91.41 [88.44; 93.82] | 0.384 *** | |

| Psychosom | 83.12 [77.65; 87.71] | 61.03 [57.25; 64.71] | |||

| Girls | 2021 | HRQoL | 54.23 [49.99; 58.44] | 90.23 [86.62; 93.14] | 0.448 *** |

| Psychosom | 89.85 [86.11; 92.87] | 55.28 [51.09; 59.42] | |||

| 2022 | HRQoL | 49.26 [45.21; 53.31] | 93.48 [90.45; 95.78] | 0.440 *** | |

| Psychosom | 92.57 [89.15; 95.18] | 52.76 [48.85; 56.65] | |||

| Outcome | Gender | COP-S | Intercept # | Age # | Sociodemographic Condition #,† | Parent’s Burden #,‡ | Child’s Burden #,§ | Family Climate # | Psychosomatic Complaints # | Model Fit (Nagelkerke’s R2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms of Anxiety | Boys | 2021 | 0.052 *** | 1.582 *** [1.444; 1.731] | 0.227 | |||||

| 2022 | 0.047 *** | 1.870 ** [1.285; 2.741] | 1.697 * [1.085; 2.647] | 1.465 *** [1.341; 1.595] | 0.218 | |||||

| Girls | 2021 | 0.024 *** | 1.130 ** [1.041; 1.243] | 1.565 *** [1.452; 1.692] | 0.295 | |||||

| 2022 | 0.011 ** | 1.177 ** [1.063; 1.289] | 1.823 ** [1.275; 2.806] | 1.633 *** [1.511; 1.768] | 0.378 | |||||

| Depressive symptoms | Boys | 2021 | 0.005 *** | 1.165 ** [1.014; 1.347] | 2.810 *** [1.657; 4.666] | 1.522 *** [1.347; 1.706] | 0.257 | |||

| 2022 | 0.005 *** | 1.178 ** [1.062; 1.315] | 1.597 *** [1.421; 1.786] | 0.205 | ||||||

| Girls | 2021 | 0.001 *** | 1.097 * [1.003; 1.207] | 1.232 *** [1.097; 1.381] | 2.475 *** [1.580; 3.760] | 1.731 *** [1.552; 1.933] | 0.415 | |||

| 2022 | 0.004 *** | 2.287 *** [1.495; 3.649] | 2.099 *** [1.851; 2.380] | 0.458 | ||||||

| Low HRQoL | Boys | 2021 | 0.000 *** | 1.198 ** [1.098; 1.302] | 1.360 *** [1.217; 1.516] | 3.113 *** [2.038; 4.728] | 1.569 *** [1.425; 1.722] | 0.420 | ||

| 2022 | 0.001 *** | 1.150 *** [1.063; 1.254] | 1.680 ** [1.120; 2.439] | 1.303 [1.162; 1.463] | 2.788 *** [1.774; 4.427] | 1.600 *** [1.466; 1.761] | 0.390 | |||

| Girls | 2021 | 0.000 *** | 1.120 *** [1.031; 1.220] | 3.369 ** [1.349; 8.409] | 1.547 *** [1.391; 1.757] | 4.209 *** [2.636; 6.151] | 1.741 *** [1.578; 1.912] | 0.549 | ||

| 2022 | 0.000 * | 1.170 *** [1.079; 1.278] | 1.477 *** [1.477; 1.322] | 2.592 *** [1.666; 1.947] | 1.782 *** [1.622; 1.947] | 0.524 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barbieri, V.; Piccoliori, G.; Mahlknecht, A.; Plagg, B.; Ausserhofer, D.; Engl, A.; Wiedermann, C.J. Adolescent Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Interplay of Age, Gender, and Mental Health Outcomes in Two Consecutive Cross-Sectional Surveys in Northern Italy. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 643. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080643

Barbieri V, Piccoliori G, Mahlknecht A, Plagg B, Ausserhofer D, Engl A, Wiedermann CJ. Adolescent Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Interplay of Age, Gender, and Mental Health Outcomes in Two Consecutive Cross-Sectional Surveys in Northern Italy. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(8):643. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080643

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarbieri, Verena, Giuliano Piccoliori, Angelika Mahlknecht, Barbara Plagg, Dietmar Ausserhofer, Adolf Engl, and Christian J. Wiedermann. 2023. "Adolescent Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Interplay of Age, Gender, and Mental Health Outcomes in Two Consecutive Cross-Sectional Surveys in Northern Italy" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 8: 643. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080643

APA StyleBarbieri, V., Piccoliori, G., Mahlknecht, A., Plagg, B., Ausserhofer, D., Engl, A., & Wiedermann, C. J. (2023). Adolescent Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Interplay of Age, Gender, and Mental Health Outcomes in Two Consecutive Cross-Sectional Surveys in Northern Italy. Behavioral Sciences, 13(8), 643. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080643