How China’s Great Bay Area Policies Affect the National Identity of Hong Kong Youth—A Study of a Quasi-Natural Experiment Based on the Difference-in-Differences Model

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Basis and Research Hypothesis

2.1. National Identity from the Perspective of Acculturation

2.2. The Effect of the GBA Policies on National Identity

2.3. The Role of Cultural Adaptation and Government Trust in Policy Effect

2.4. Heterogeneity of the Policy Effect among Groups

3. Research Design

3.1. Model Setting

3.2. Data Sources and Operated Variables

3.3. Descriptive Statistics

4. Empirical Analysis Results

4.1. Analysis Results Based on the DID Model

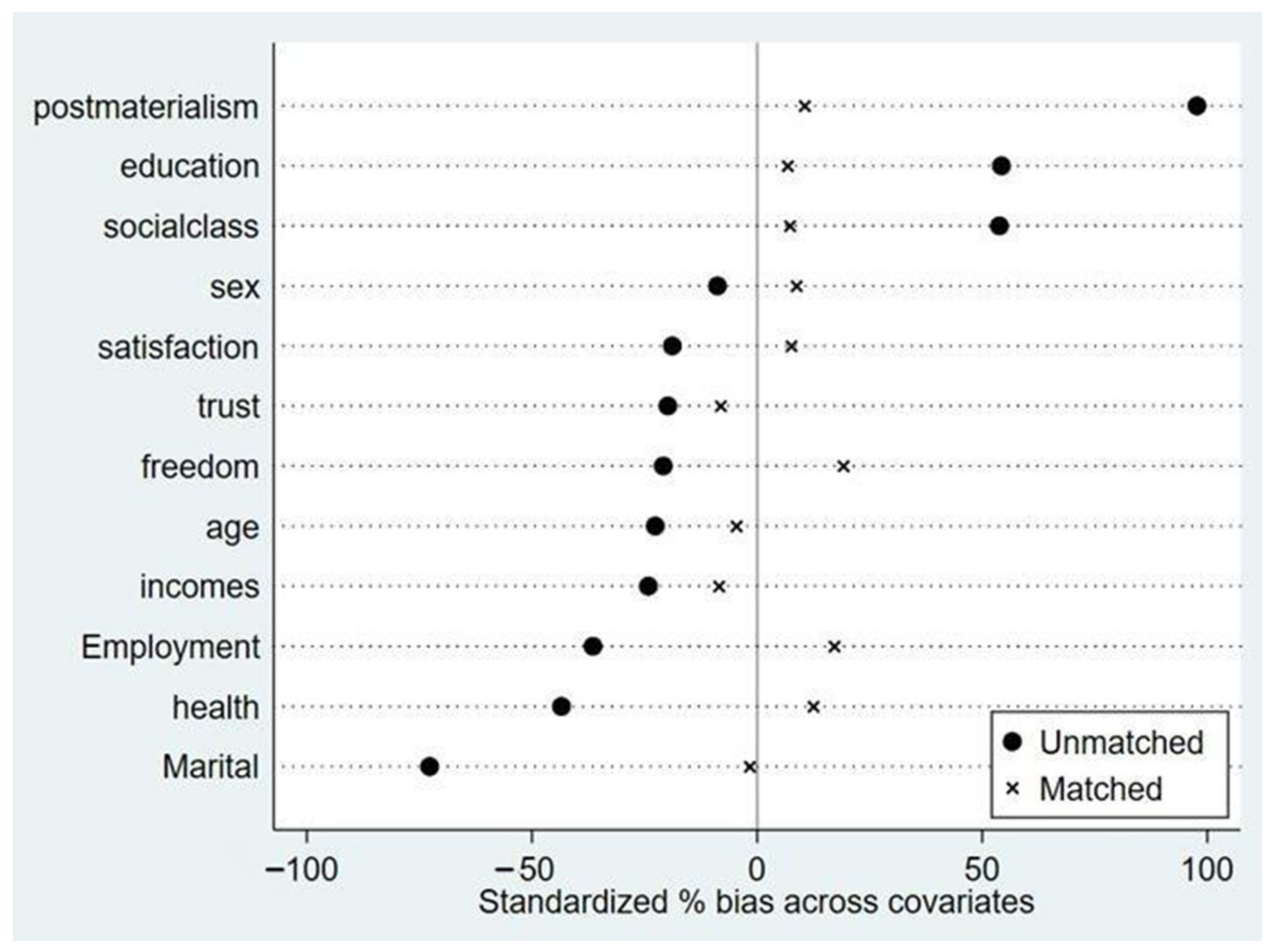

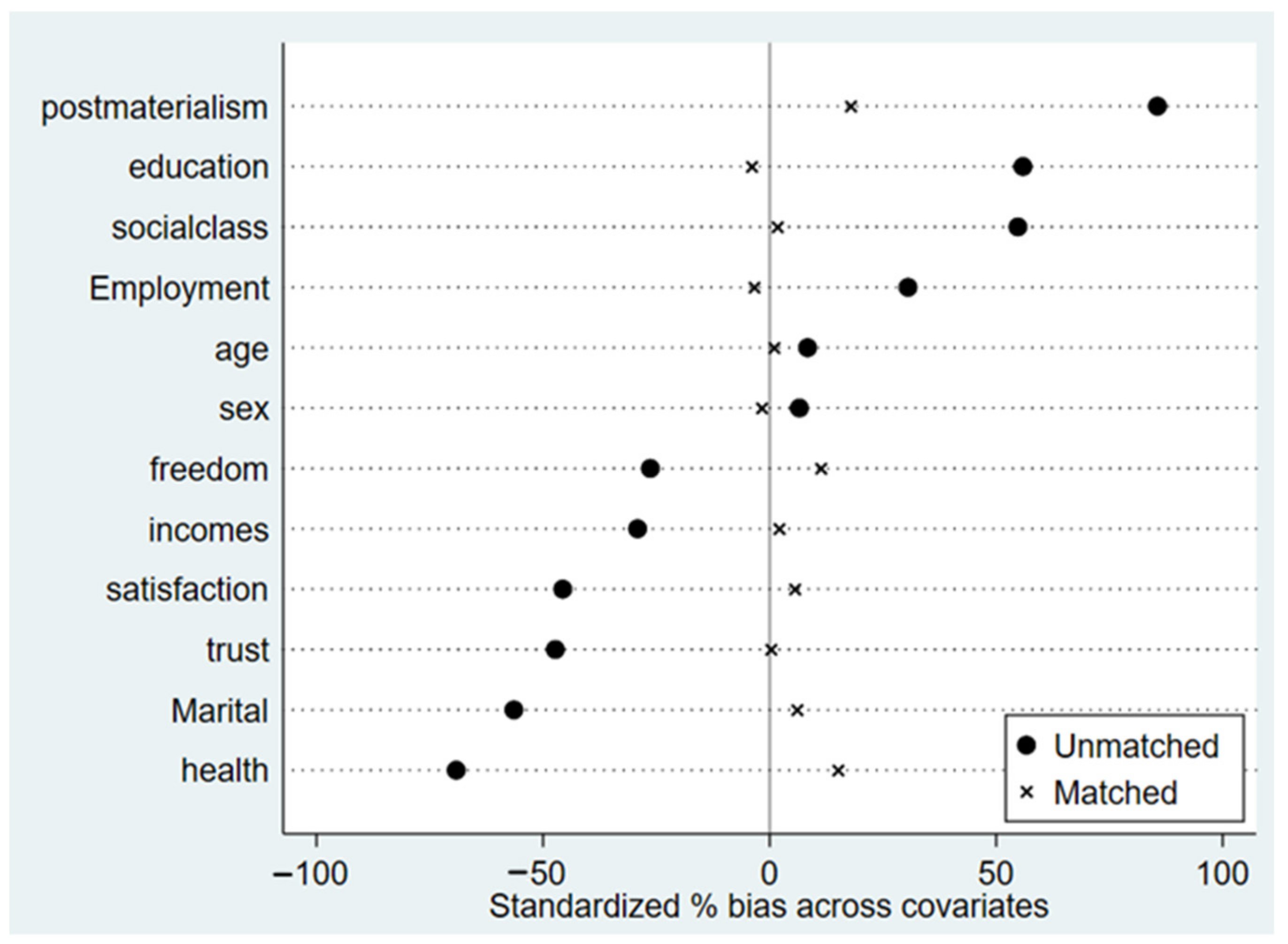

4.2. Robustness Test: Propensity Score Matching (PSM)-DID Model Results

4.2.1. Propensity Score Matching

4.2.2. Balance Diagnostics after Matching

4.2.3. Average Treatment Effect

4.2.4. Robustness Test of the Policy Effect

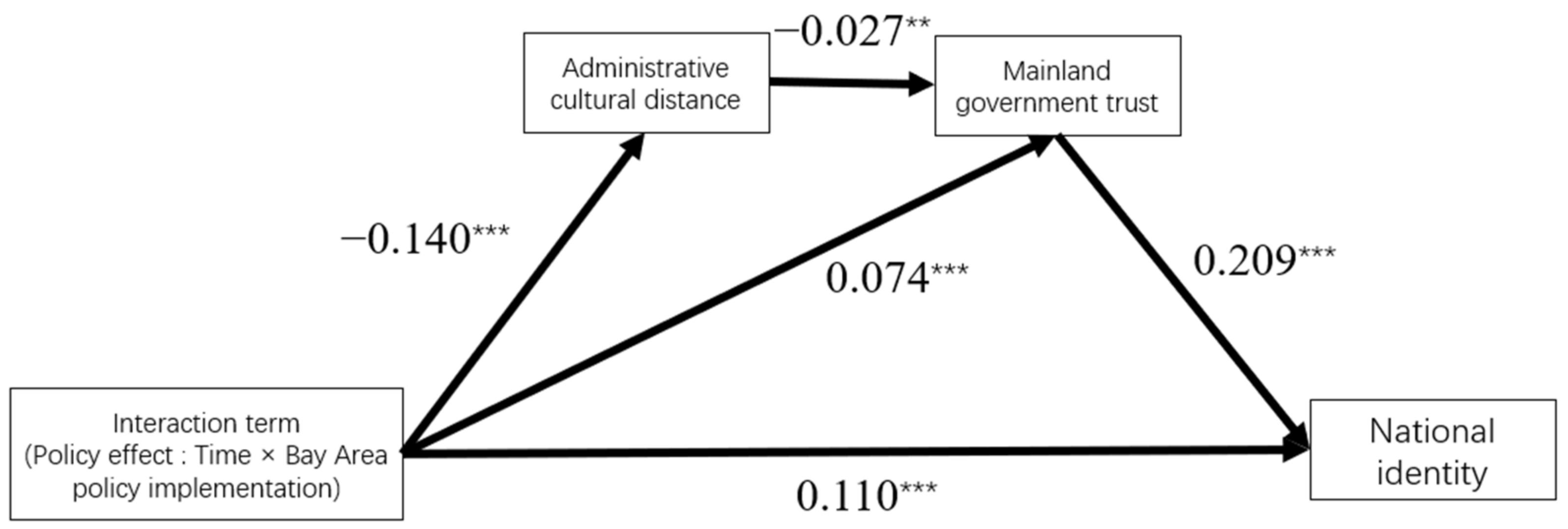

4.3. Analysis of the Mechanism of the Policy Effects

4.4. Robustness Testing of the Subjective Variables Explaining the Subjective Variables

4.5. Heterogeneity of the Policy Effect among Groups

5. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dovidio, J.F.; Gaertner, S.L.; Saguy, T. Another view of “we”: Majority and minority group perspectives on a common ingroup identity. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 18, 296–330. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, M.; Wu, C.; Sun, H. Research on the implementation mechanism of strengthening the national identity of the youth in Hong Kong and Macao. Youth Explor. 2021, 3, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Huo, W.; Zhang, J. Policies for Hong Kong youth development in the Mainland and the integrated development of the GBA: An empirical study based on HKPSSD Data. J. Public Adm. 2020, 13, 176–200. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, B. Opportunities and challenges to enhance the national identity of Hong Kong And Macao youths from the perspective of ecosystem. Contemp. Youth Res. 2019, 6, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- An, D. The national identity of Hong Kong youth during the construction of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao China’s Bay Area: Contemporary value, realistic dilemma and reconstruction path. Lingnan J. 2020, 1, 40–46. [Google Scholar]

- King, G.; Keohane, R.O.; Verba, S. Designing social inquiry scientific inference in qualitative research. Contemp. Sociol. 1994, 24, 424. [Google Scholar]

- Park, R.E. Human Migration and the Marginal Man; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA; p. 1928.

- Yieh, T.K. The Adjustment Problems of Chinese Graduate Students in American Universities. Ph.D. Dissertation, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Redfield, R.; Linton, R.; Herskovits, M.J. Memorandum for the study of acculturation. Am. Anthropol. 2010, 38, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J.W. Integration and multiculturalism: Ways towards social solidarity. Pap. Soc. Represent. 2011, 20, 2.1–2.21. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. Psychology of Intergroup Relations 1986, 13, 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, P. Analysis of Identity Research. Forward Position 2019, 2, 68–70. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, J.; Guo, Q. The psychological path of conceptual boundary and structural dimension of national identity. J. Southwest Minzu Univ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2019, 40, 214–221. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J. The time dimension of national identity: An analysis based on intergenerational justice. J. Jiangsu Adm. Inst. 2020, 5, 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, B. Understanding national identity—Reflections on the constituent elements, predicament and realization mechanism of national identity. Soc. Sci. Front. 2018, 7, 203–209. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S. The political logic of modern national identity construction. Soc. Sci. China 2013, 8, 22–205. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, B. On the formation of children’s national identity. Educ. Res. Exp. 2000, 2, 33–73. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, J.; Hogg, M.A.; Livingstone, A.G.; Choi, H.S. From uncertain boundaries to uncertain identity: Effects of entitativity threat on identity–uncertainty and emigration. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 49, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Pang, Q. The role of the other in the national identity of Hong Kong college students: An empirical comparative study on the national identity of college students in Beijing and Hong Kong. J. Sun Yat-Sen Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2015, 55, 147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J.W. Family and Youth Development: Some Concepts and Findings Linked to The Ecocultural and Acculturation Models. Societies 2022, 12, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Yang, A. The psychological integration mechanism of Hong Kong youth’s national identity. Contemp. Youth Res. 2018, 6, 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Babiker, I.E.; Cox, J.L.; Miller, P.M. The measurement of cultural distance and its relationship to medical consultations, symptomatology and examination performance of overseas students at Edinburgh University. Soc. Psychiatry 2004, 15, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Yang, L. Location determinants of China’s OFDI—Based on the Test of Geographical Distance and Cultural Distance. Econ. Geogr. 2021, 32, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, W.; Chen, H. How does cultural integration affect the bilateral trade between China and countries along the Belt and Road Initiative?—An empirical test based on micro trade data from 1995 to 2013. J. Int. Trade 2016, 2, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. What kind of trust and why trust?—An empirical analysis of the current situation and sources of public political trust in contemporary China. J. Public Manag. 2014, 11, 16–140. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, N. Investigation on the formation of national identity: From the perspective of conceptual reproduction of political rituals. J. Anhui Norm. Univ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 49, 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, X. Governance and Chaos in Hong Kong: Political Imagination in 2047; People’s Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fred, W. Riggs. International relations as a prismatic system. World Politics 1961, 14, 144–181. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, M.; Shils, E.A. Max Weber on Law in Economy and Society; Havard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.H.; Bilsky, W. Toward a universal psychological structure of human values. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 53, 550. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Song, F.; Zhang, Y. A review of the theoretical model of acculturation. Cult. Ind. 2022, 24, 53–55. [Google Scholar]

- Dallinger, U. Public support for redistribution: What factors explain the international differences? Journal of European Social Policy. 2010, 20, 333–349. Hu, A. Propensity score matching and causal inference: A methodological review. Sociol. Stud. 2012, 1, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, T.J. Cultural values and political trust—A comparison of the People’s Republic of China and Taiwan. Comp. Politics 2001, 33, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. A new approach to the study of values and behavior patterns of the new generation. Acad. Mon. 2021, 53, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machura, S.; Jones, S.O.; Würgler, A.; Cuthbertson, J.; Hemmings, A. National Identity and Distrust in the Police: The Case of North West Wales; SAGE Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhardt, H.C.; Li, L.C.; Jiang, Y. The identity shift in Hong Kong since 1997: Measurement and explanation. J. Contemp. China 2018, 27, 261–276. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, B.; Zhang, D. How is political trust transformed into political identity—An analysis based on the data of the comprehensive survey of China’s social conditions in 2019. J. Shanghai Adm. Inst. 2022, 23, 52–65. [Google Scholar]

- Alvesson, M.; Lee Ashcraft, K.; Thomas, R. Identity matters: Reflections on the construction of identity scholarship in organization studies. Organization 2008, 15, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.H. Hidden order: How adaptation builds complexity. Leonardo 1995, 29, 453. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Bian, Y. Constructing an aggregated policy evaluation model. J. Manag. World 2022, 38, 92–104. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, H. Knowledge construction of behavioral public policy research: Three levels and paradigm selection. Chin. Public Adm. 2021, 9, 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J. Policy target group factor influencing the effective implementation of public policy. Acad. Forum 2007, 197, 53–57. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Z.; Forrest, D.; McHale, I.G. Happiness and Job Satisfaction in a Casino-Dominated Economy. J. Gambl. Stud. 2013, 29, 471–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.E.; Jang, S.J. National identity, national pride, and happiness: The case of South Korea. Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 121, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, E.; Ren, C. Analysis of the political and economic reasons of Hong Kong’s anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill movement. J. Manag. 2019, 32, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hang, C.; Hu, A. The essence of the phenomenon of spiritual poverty is individual failure—From the perspective of behavioral science. J. Chin. Acad. Gov. 2017, 4, 97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Ahlfeldt, G.M. Weights to address non-parallel trends in panel difference-in-differences models. CESifo Econ. Stud. 2018, 64, 216–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Hou, J.; Xia, L.; Zhu, S. The Belt and Road Initiative and RMB internationalization—Empirical evidence from real RMB trading data. J. Manag. World 2022, 38, 49–67. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, F.; Luo, X.; Song, J. A review of the research on the national identity of Hong Kong youth. Contemp. Youth Res. 2016, 6, 103–122. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. Nationality and espoused values of managers. J. Appl. Psychol. 1976, 61, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, T.F.; Tropp, L.R.; Wagner, U.; Christ, O. Recent advances in intergroup contact theory. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2011, 35, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhang, X. The guiding ways of young people’s national identity in Hong Kong. Theor. Res. 2018, 347, 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y. Development of civic education in Hong Kong based on the concept of active citizenship—The perspective of national identity. J. South China Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2011, 1, 109–114+159. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, Y. The rhetorical construction of national identity in Hong Kong media—Taking the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area news text of the South China Morning Post as an example. Contemp. Rhetor. 2021, 227, 54–66. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman, J.J.; Hidehiko, I.; Todd, P.E. Matching as an econometric evaluation estimator: Evidence from evaluating a job training programme. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1997, 4, 22–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Entire Sample | Control Group: HK Youth | Treatment Group: Mainland Youth (Except Those in Guangdong Province) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M | %/SD | M | %/SD | M | %/SD |

| Implementation of Bay Area Policy | 0.252 | 0.434 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Time | 0.605 | 0.489 | 0.646 | 0.478 | 0.579 | 0.494 |

| National identity | 3.163 | 0.631 | 3.007 | 0.617 | 3.263 | 0.619 |

| Mainland Government Trust | 2.787 | 1.000 | 1.906 | 0.810 | 3.320 | 0.632 |

| Administrative Cultural Distance | 5.156 | 6.360 | 4.227 | 5.572 | 5.750 | 6.751 |

| Sex | 0.456 | 0.498 | 0.457 | 0.498 | 0.456 | 0.498 |

| Employment Status | 0.751 | 0.433 | 0.763 | 0.426 | 0.743 | 0.437 |

| Marital Status | 0.589 | 0.492 | 0.406 | 0.491 | 0.706 | 0.456 |

| Age | 29.933 | 6.740 | 29.780 | 6.851 | 30.031 | 6.668 |

| Income | 6.297 | 1.686 | 6.027 | 1.593 | 6.470 | 1.721 |

| Social class | 2.583 | 0.839 | 2.856 | 0.870 | 2.408 | 0.770 |

| Education level | 2.372 | 0.589 | 2.566 | 0.515 | 2.249 | 0.601 |

| Self-assessed Feeling of Freedom | 6.785 | 1.833 | 6.509 | 1.693 | 6.960 | 1.896 |

| Health Condition | 3.875 | 0.805 | 3.592 | 0.727 | 4.056 | 0.801 |

| Life Satisfaction | 6.837 | 1.853 | 6.440 | 1.665 | 7.090 | 1.922 |

| Post-materialist Values | 1.860 | 1.254 | 2.503 | 1.317 | 1.449 | 1.017 |

| Explained Variable | National Identity | National Identity | Administrative Cultural Distance | Government Trust |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

| Time | −0.111 *** | −0.109 *** | 0.230 *** | 0.037 ** |

| (Based on 2014) | (0.028) | (0.029) | (0.310) | (0.032) |

| Implementation of the Policies | −0.280 *** | −0.234 *** | 0.029 | −0.690 *** |

| (Mainland as the Control Group) | (0.037) | (0.040) | (0.432) | (0.050) |

| Interactive Term | 0.127 *** | 0.141 *** | −0.142 *** | 0.089 *** |

| (Time × Implementation of the Policies) | (0.047) | (0.048) | (0.479) | (0.056) |

| Sex | 0.022 | 0.046 ** | 0.023 * | |

| (0.023) | (0.231) | (0.026) | ||

| Age | 0.038 | −0.003 | 0.022 | |

| (0.002) | (0.023) | (0.003) | ||

| Income | 0.018 | −0.024 | −0.002 | |

| (0.008) | (0.093) | (0.009) | ||

| Social Class | −0.014 | −0.056 ** | 0.040 ** | |

| (0.017) | (0.179) | (0.019) | ||

| Employment Status | −0.061 *** | −0.001 | −0.042 *** | |

| (0.037) | (0.388) | (0.043) | ||

| Marital status | 0.024 | 0.031 | 0.036 * | |

| (0.031) | (0.313) | (0.037) | ||

| Education Level | 0.033 * | −0.088 *** | −0.040 *** | |

| (0.021) | (0.230) | (0.024) | ||

| Self-assessed Feeling of Freedom | 0.013 | 0.042 * | 0.007 | |

| (0.008) | (0.080) | (0.009) | ||

| Health Condition | 0.060 *** | 0.033 | 0.026 * | |

| (0.016) | (0.160) | (0.019) | ||

| Social Trust | 0.004 | −0.042 ** | 0.071 *** | |

| (0.024) | (0.241) | (0.027) | ||

| Life Satisfaction | 0.069 *** | 0.037 | 0.057 *** | |

| (0.008) | (0.085) | (0.00901) | ||

| Post-materialist Values | −0.064 *** | −0.003 | −0.107 *** | |

| (0.010) | (0.095) | (0.011) | ||

| Con | 3.343 *** | 2.852 *** | 4.749 *** | 2.923 *** |

| (0.019) | (0.140) | (1.486) | (0.162) | |

| R-sq | 0.046 | 0.066 | 0.062 | 0.532 |

| F | 54.93 | 15.00 | 11.58 | 227.6 |

| N | 3032 | 2946 | 2946 | 2946 |

| Percent Bias | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Before Matching | After Matching | Difference t-Test after Matching |

| Sex | 6.6 | −1.8 | −0.32 |

| Age | 8.4 | 1.0 | 0.19 |

| Income | −29.1 | 2.1 | 0.41 |

| Social Class | 54.8 | 1.7 | 0.34 |

| Employment Status | 30.5 | −9.5 | −0.70 |

| Marital Status | −56.4 | 6.1 | 1.09 |

| Education Level | 55.9 | −4.0 | −0.80 |

| Feeling of Freedom | −26.3 | 11.3 | 2.31 ** |

| Health Condition | −69.2 | 15.1 | 2.82 *** |

| Social Trust | −47.3 | 0.3 | 0.05 |

| Life Satisfaction | −45.7 | 5.6 | 1.05 |

| Post-materialist Values | 85.6 | 17.9 | 3.46 *** |

| Group | Matching Method | Sample | Control Group | Treatment Group | Difference | Standard Error | T Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Unmatched | Unmatched | 3.263 | 3.007 | 0.256 | 0.023 | 10.991 *** |

| 2 | 1:1 nearest neighbor matching | ATT | 3.205 | 3.044 | 0.161 | 0.041 | 3.962 *** |

| 3 | 4:1 nearest neighbor matching | ATT | 3.232 | 3.018 | 0.213 | 0.029 | 7.284 *** |

| 4 | Caliper matching | ATT | 3.192 | 3.022 | 0.170 | 0.032 | 5.291 *** |

| 5 | Kernel matching | ATT | 3.343 | 2.987 | 0.356 | 0.035 | 10.119 *** |

| 6 | MDM | ATT | 3.204 | 3.021 | 0.182 | 0.031 | 5.908 *** |

| Explained Variable | National Identity | National Identity | Administrative Cultural Distance | Government Trust |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 |

| Time (Based on 2014) | −0.162 *** (0.055) | −0.162 *** (0.055) | 0.187 *** (0.572) | 0.021 (0.063) |

| Implementation of the Policies (Mainland as the Control Group) | −0.252 *** (0.048) | −0.243 *** (0.049) | −0.012 (0.541) | −0.676 *** (0.065) |

| Interactive Term (Time×Implementation of the Policies) | 0.191 *** (0.068) | 0.202 *** (0.067) | −0.112 * (0.678) | 0.133 *** (0.079) |

| Cons | 3.332 *** (0.036) | 2.995 *** (0.201) | 4.867 ** (2.036) | 3.063 *** (0.255) |

| Control variable | Uncontrolled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| R2 | 0.031 | 0.047 | 0.047 | 0.450 |

| F | 20.90 | 6.055 | 4.587 | 103.9 |

| N | 1536 | 1536 | 1536 | 1536 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. National Identity | 1.00 | ||

| 2. Government Trust | 0.240 *** | 1.00 | |

| 3. Administrative Cultural Distance | 0.041 ** | 0.064 *** | 1.00 |

| Goodness-of-Fit Index | Value | Evaluation Criterion |

|---|---|---|

| χ2/df | 4.761 | <5 |

| RMSEA | 0.035 | <0.08 |

| SRMR | 0.008 | <0.05 |

| CFI | 0.998 | >0.9 |

| TLI | 0.982 | >0.9 |

| AIC | 40,087.673 | |

| BIC | 40,189.962 |

| Explained Variable | Mainland Government Trust | Mainland Government Trust | National Identity | National Identity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Model 9 | Model 10 | Model 11 | Model 12 |

| Administrative Cultural Distance | −0.036 *** | −0.030 ** | ||

| (0.002) | (0.002) | |||

| Mainland Government Trust | 0.185 *** | 0.171 *** | ||

| (0.018) | (0.018) | |||

| Time | 0.046 *** | 0.041 *** | −0.116 *** | −0.118 *** |

| (Taking the Year of 2014 as a Reference) | (0.032) | (0.032) | (0.028) | (0.028) |

| Bay Area Policy Implementation | −0.689 *** | −0.724 *** | −0.106 *** | −0.139 *** |

| (with the Mainland as the Reference Group) | (0.050) | (0.050) | (0.044) | (0.046) |

| Interaction Term | 0.084 *** | 0.087 *** | 0.124 *** | 0.125 *** |

| (Time × Bay Area Policy Implementation) | (0.056) | (0.056) | (0.047) | (0.047) |

| Trust Tendency | 0.104 *** | 0.071 *** | ||

| (0.018) | (0.016) | |||

| Other Controlled Variables | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| _cons | 2.950 *** | 3.067 *** | 2.510 *** | 2.584 *** |

| (0.162) | (0.160) | (0.152) | (0.153) | |

| R-sq | 0.534 | 0.543 | 0.082 | 0.087 |

| F | 214.3 | 212.3 | 16.37 | 16.10 |

| N | 2946 | 2938 | 2946 | 2938 |

| Explained Variable | Employed | Unemployed |

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Model 13 | Model 14 |

| Time (Based on 2014) | −0.109 *** (0.031) | −0.154 *** (0.076) |

| Implementation of the Policies (Mainland as the Control Group) | −0.247 *** (0.044) | −0.203 *** (0.094) |

| Interactive Term (Time × Implementation of the Policies) | 0.143 *** (0.053) | 0.154 * (0.113) |

| Cons | 2.644 *** (0.156) | 3.547 *** (0.379) |

| Control variable | Controlled | Controlled |

| R2 | 0.071 | 0.083 |

| F | 14.16 *** | 3.870 *** |

| N | 2482 | 464 |

| Explained Variable | Public Sector and NGOs | For-Profit Private Sector |

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Model 15 | Model 16 |

| Time (Based on 2014) | 0.048 (0.070) | −0.123 *** (0.050) |

| Implementation of the Policies (Mainland as the Control Group) | −0.101 (0.0809) | −0.294 *** (0.066) |

| Interactive Term (Time × Implementation of the Policies) | 0.039 (0.108) | 0.225 *** (0.077) |

| Cons | 1.790 *** (0.319) | 2.612 *** (0.225) |

| Control Variable | Controlled | Controlled |

| R2 | 0.096 | 0.073 |

| F | 4.256 *** | 6.178 *** |

| N | 515 | 1061 |

| Group | Lower-Class Group | Middle-and Upper-Class Group |

|---|---|---|

| Variables | Model 17 | Model 18 |

| Time (based on 2014) | −0.142 *** (0.042) | −0.0786 ** (0.039) |

| Implementation of the Policies (Mainland as the Reference group) | −0.196 *** (0.074) | −0.249 *** (0.048) |

| Interaction Items (Time × Implementation of the Policies) | 0.116 ** (0.090) | 0.137 *** (0.059) |

| Cons | 2.738 *** (0.206) | 2.821 *** (0.163) |

| Control Variables | Controlled | Controlled |

| R2 | 0.0592 | 0.0768 |

| F | 5.775 | 10.84 |

| N | 1222 | 1724 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fu, C.; Liao, L.; Mo, T.; Chen, X. How China’s Great Bay Area Policies Affect the National Identity of Hong Kong Youth—A Study of a Quasi-Natural Experiment Based on the Difference-in-Differences Model. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 644. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080644

Fu C, Liao L, Mo T, Chen X. How China’s Great Bay Area Policies Affect the National Identity of Hong Kong Youth—A Study of a Quasi-Natural Experiment Based on the Difference-in-Differences Model. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(8):644. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080644

Chicago/Turabian StyleFu, Chengzhe, Liao Liao, Tingyang Mo, and Xiaoqing Chen. 2023. "How China’s Great Bay Area Policies Affect the National Identity of Hong Kong Youth—A Study of a Quasi-Natural Experiment Based on the Difference-in-Differences Model" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 8: 644. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080644

APA StyleFu, C., Liao, L., Mo, T., & Chen, X. (2023). How China’s Great Bay Area Policies Affect the National Identity of Hong Kong Youth—A Study of a Quasi-Natural Experiment Based on the Difference-in-Differences Model. Behavioral Sciences, 13(8), 644. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080644