What Motivates Chinese Mothers’ Involvement in Adolescents’ Learning? Longitudinal Investigation on the Role of Mothers’ Expectations of Adolescents’ Family Obligations and Adolescents’ Academic Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Parental Involvement in Children’s Learning in China

1.2. Chinese Parents’ Expectations of Adolescents’ Family Obligations and Involvement in Adolescents’ Learning

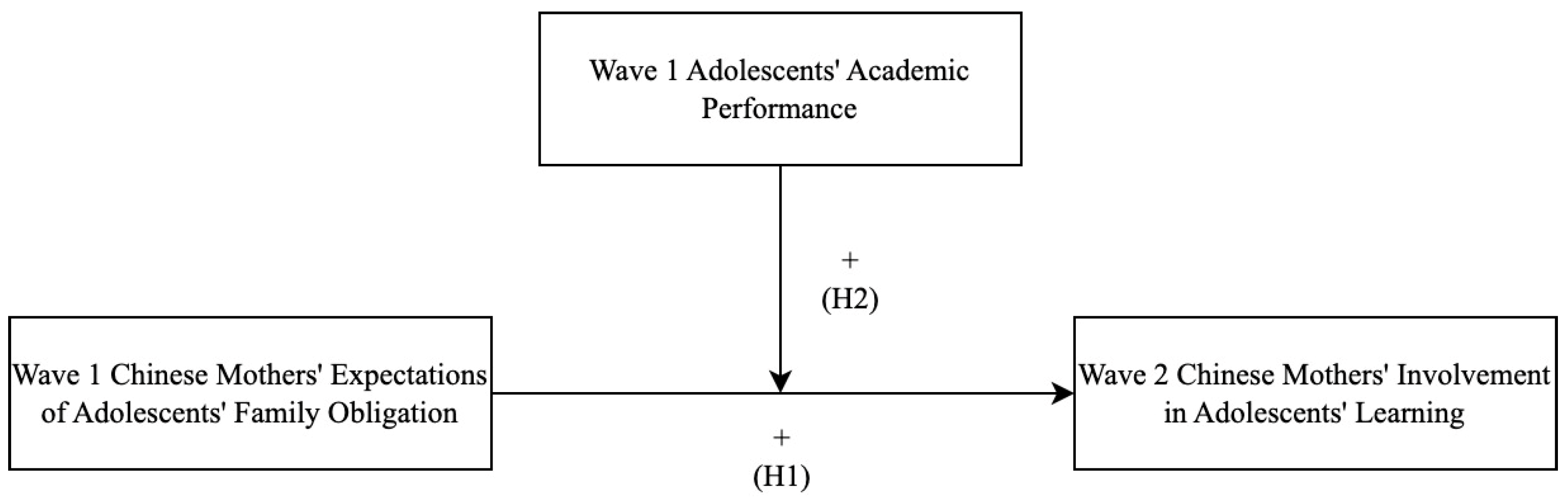

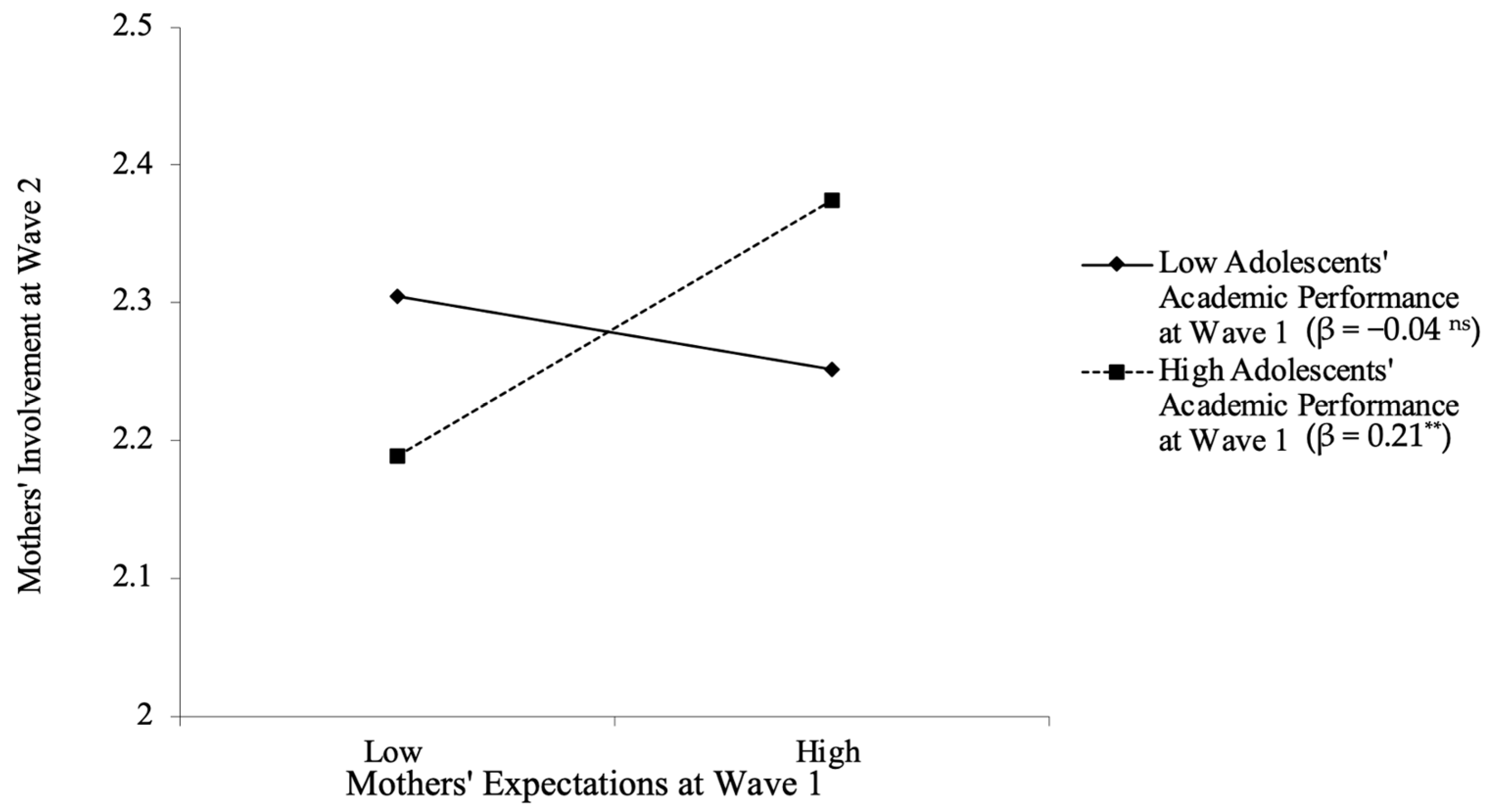

1.3. The Moderating Role of Adolescents’ Academic Performance

1.4. Overview of the Current Research

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Mothers’ Involvement in Adolescents’ Learning

2.3.2. Mothers’ Expectations of Adolescents’ Family Obligations

2.3.3. Adolescents’ Academic Performance

2.4. Data Analyses Plan

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

3.2. Central Analyses

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- I help with homework.

- I know how my child is doing in school.

- I check to make sure my child’s homework is completed.

- I enforce family rules or expectations about completing homework.

- 5.

- I attend parent–teacher organization meetings.

- 6.

- I attend parent–teacher conferences.

- 7.

- I volunteer at my child’s school.

- 8.

- I watch my child in sports or school activities.

- 9.

- I talk to my child about what he/she is learning in school.

- 10.

- I help my child select which courses to take (e.g., tutoring class).

- 11.

- I talk with my child about how his/her courses in school will prepare him/her for future careers.

- 12.

- I talk with my child about his/her educational plans for the future.

- 13.

- I help my child select which courses to take (e.g., extracurricular interest class).

Appendix B

- Spend time at home with parents.

- Spend holidays with parents.

- Help with housework that parents need done.

- Respect parents.

- Obey parents.

- Please parents.

- Look after parents when they get older.

- Help parents financially when they get older.

- Stay in contact with parents when they get older.

References

- Wigfield, A.; Eccles, J.S. 35 Years of Research on Students’ Subjective Task Values and Motivation: A Look Back and a Look Forward. In Advances in Motivation Science; Elsevier Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; Volume 7, pp. 161–198. ISBN 978-0-12-819634-2. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, N.E.; Tyson, D.F. Parental Involvement in Middle School: A Meta-Analytic Assessment of the Strategies That Promote Achievement. Dev. Psychol. 2009, 45, 740–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grolnick, W.S.; Pomerantz, E.M. Should Parents Be Involved in Their Children’s Schooling? Theory Pract. 2022, 61, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. won Meta-Analysis of Parental Involvement and Achievement in East Asian Countries. Educ. Urban Soc. 2020, 52, 312–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barger, M.M.; Kim, E.M.; Kuncel, N.R.; Pomerantz, E.M. The Relation between Parents’ Involvement in Children’s Schooling and Children’s Adjustment: A Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2019, 145, 855–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover-Dempsey, K.V.; Walker, J.M.T.; Sandler, H.M.; Whetsel, D.; Green, C.L.; Wilkins, A.S.; Closson, K. Why Do Parents Become Involved? Research Findings and Implications. Elem. Sch. J. 2005, 106, 105–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomerantz, E.M.; Ng, F.F.-Y.; Cheung, C.S.-S.; Qu, Y. Raising Happy Children Who Succeed in School: Lessons from China and the United States. Child Dev. Perspect. 2014, 8, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, R.K.; Tseng, V. Parenting of Asians. In Handbook of Parenting: Volume 4 Social Conditions and Applied Parenting; Psychology Press: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2002; Volume 4, pp. 59–93. ISBN 0-8058-3778-7. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Y.; Pomerantz, E.M.; Wang, M.; Cheung, C.; Cimpian, A. Conceptions of Adolescence: Implications for Differences in Engagement in School over Early Adolescence in the United States and China. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 1512–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q. Filial Piety. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Lifespan Human Development; Bornstein, M.H., Ed.; SAGE Reference: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018; Volume 2, pp. 880–882. [Google Scholar]

- Bedford, O.; Yeh, K.-H. Evolution of the Conceptualization of Filial Piety in the Global Context: From Skin to Skeleton. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 570547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunkkari, M.; Aunola, K.; Hirvonen, R.; Silinskas, G.; Kiuru, N. The Quality of Maternal Homework Involvement: The Role of Adolescent and Maternal Factors. Merrill-Palmer Q. 2021, 67, 94–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Qin, X.; Wang, Q.; Ren, P. Parental Involvement in Adolescents’ Learning and Academic Achievement: Cross-Lagged Effect and Mediation of Academic Engagement. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 1811–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomerantz, E.M.; Kim, E.M.; Cheung, C.S.-S. Parents’ Involvement in Children’s Learning. In APA Educational Psychology Handbook, Vol 2: Individual Differences and Cultural and Contextual Factors; Harris, K.R., Graham, S., Urdan, T., Graham, D., Royer, J.M., Zeidner, M., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; Volume 2, pp. 417–440. [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz, E.M.; Grolnick, W.S. The Role of Parenting in Children’s Motivation and Competence: What Underlies Facilitative Parenting? In Handbook of Competence and Motivation: Theory and Application; Elliot, A.J., Dweck, C.S., Yeager, D.S., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 566–585. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, F.F.-Y.; Wei, J. Delving into the Minds of Chinese Parents: What Beliefs Motivate Their Learning-Related Practices? Child Dev. Perspect. 2020, 14, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Li, J.; Bempechat, J. Reconceptualizing Parental Involvement: A Sociocultural Model Explaining Chinese Immigrant Parents’ School-Based and Home-Based Involvement. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 57, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullis, I.V.S.; Martin, M.O.; Foy, P.; Kelly, D.L.; Fishbein, B. TIMSS 2019 International Results in Mathematics and Science; Boston College, TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center: Chestnut Hill, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. PISA 2018 Results (Volume i): What Students Know and Can Do; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, C.S.-S.; Pomerantz, E.M. Value Development Underlies the Benefits of Parents’ Involvement in Children’s Learning: A Longitudinal Investigation in the United States and China. J. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 107, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikels, C. Filial Piety: Practice and Discourse in Contemporary East Asia; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni, A.J.; Zhang, W. Attitudes toward Family Obligation among Adolescents in Contemporary Urban and Rural China. Child Dev. 2004, 75, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Way, N.; Okazaki, S.; Zhao, J.; Kim, J.J.; Chen, X.; Yoshikawa, H.; Jia, Y.; Deng, H. Social and Emotional Parenting: Mothering in a Changing Chinese Society. Asian Am. J. Psychol. 2013, 4, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, K.-H.; Yi, C.-C.; Tsao, W.-C.; Wan, P.-S. Filial Piety in Contemporary Chinese Societies: A Comparative Study of Taiwan, Hong Kong, and China. Int. Sociol. 2013, 28, 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.-P.; Yi, C.-C. A Comparative Analysis of Intergenerational Relations in East Asia. Int. Sociol. 2013, 28, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.C. In Search of the Confucian Family: Interviews with Parents and Their Middle School Children in Guangzhou, China. J. Adolesc. Res. 2014, 29, 765–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, C.S.L.; Leung, C.Y.Y.; Bayram Özdemir, S. Chinese Malaysian Adolescents’ Social-Cognitive Reasoning Regarding Filial Piety Dilemmas. Child Dev. 2018, 89, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X. Exploring Cultural Meanings of Adaptive and Maladaptive Behaviors in Children and Adolescents: A Contextual-Developmental Perspective. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2020, 44, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, J.T. Perceived Parental Sacrifice, Filial Piety and Hopelessness among Chinese Adolescents: A Cross-Lagged Panel Study. J. Adolesc. 2020, 81, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pomerantz, E.M.; Qin, L.; Wang, Q.; Chen, H. Changes in Early Adolescents’ Sense of Responsibility to Their Parents in the United States and China: Implications for Academic Functioning. Child Dev. 2011, 82, 1136–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, Y.; Pomerantz, E.M.; Wang, Q.; Ng, F.F.Y. Early Adolescents’ Stereotypes About Teens in Hong Kong and Chongqing: Reciprocal Pathways with Problem Behavior. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 56, 1092–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Pomerantz, E.M.; Deng, C. Mothers’ Goals for Adolescents in the United States and China: Content and Transmission. J. Res. Adolesc. 2016, 26, 126–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J.S.; Wigfield, A. From Expectancy-Value Theory to Situated Expectancy-Value Theory: A Developmental, Social Cognitive, and Sociocultural Perspective on Motivation. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 61, 101859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Pomerantz, E.M.; Ng, F.F.-Y.; Yu, Y.; Wang, M.; Wang, Q. Why Does Parents’ Involvement in Youth’s Learning Vary across Elementary, Middle, and High School? Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 56, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Hou, Y.; Wang, Q.; Yu, C. Intergenerational Transmission of Educational Aspirations in Chinese Families: Identifying Mediators and Moderators. J. Youth Adolesc. 2018, 47, 1238–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silinskas, G.; Kiuru, N.; Aunola, K.; Lerkkanen, M.K.; Nurmi, J.E. The Developmental Dynamics of Children’s Academic Performance and Mothers’ Homework-Related Affect and Practices. Dev. Psychol. 2015, 51, 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huzhou Bureau of Statistics. Huzhou Statistics Yearbook; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, N.E.; Witherspoon, D.P.; Bartz, D. Parental Involvement in Education during Middle School: Perspectives of Ethnically Diverse Parents, Teachers, and Students. J. Educ. Res. 2018, 111, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, E.; Dotterer, A.M. Parental Involvement and Adolescent Academic Outcomes: Exploring Differences in Beneficial Strategies across Racial/Ethnic Groups. J. Youth Adolesc. 2018, 47, 1332–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.P.; Ho, M.H.R. Principles and Practice in Reporting Structural Equation Analyses. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Methodology in the social sciences; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4625-2334-4. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Y.; Pomerantz, E.M. Divergent School Trajectories in Early Adolescence in the United States and China: An Examination of Underlying Mechanisms. J. Youth Adolesc. 2015, 44, 2095–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosseel, Y. Lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. R Package Version 0.5-15. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, J.T.Y.; Shek, D.T.L. Parental Sacrifice, Filial Piety and Adolescent Life Satisfaction in Chinese Families Experiencing Economic Disadvantage. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2020, 15, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.E.; Sheridan, S.M.; Kim, E.M.; Park, S.; Beretvas, S.N. The Effects of Family-School Partnership Interventions on Academic and Social-Emotional Functioning: A Meta-Analysis Exploring What Works for Whom. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 32, 511–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, T.F.; Costigan, C.L. The Development of Children’s Ethnic Identity in Immigrant Chinese Families in Canada: The Role of Parenting Practices and Children’s Perceptions of Parental Family Obligation Expectations. J. Early Adolesc. 2009, 29, 638–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Fong, V.L. How Parents Help Children with Homework in China: Narratives across the Life Span. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2013, 14, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Zhang, M.; Simon, M.A. The Expectation and Perceived Receipt of Filial Piety among Chinese Older Adults in the Greater Chicago Area. J. Aging Health 2014, 26, 1225–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, F.F.; Sze, I.N.; Tamis-LeMonda, C.S.; Ruble, D.N. Immigrant Chinese Mothers’ Socialization of Achievement in Children: A Strategic Adaptation to the Host Society. Child Dev. 2017, 88, 979–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Adolescents’ Academic Performance at Wave 1 | -- | |||||||

| 2. Mothers’ Expectation of Adolescents’ Family Obligations at Wave 1 | −0.03 | -- | ||||||

| 3. Mothers’ Involvement in Adolescents’ Learning at Wave 1 | 0.04 | 0.21 *** | -- | |||||

| 4. Mothers’ Involvement in Adolescents’ Learning at Wave 2 | 0.04 | 0.18 *** | 0.45 *** | -- | ||||

| 5. Adolescents’ Age | −0.20 *** | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | -- | |||

| 6. Adolescents’ Grade Level | −0.22 *** | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.68 *** | -- | ||

| 7. Adolescents’ Gender | 0.26 *** | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.02 | -- | |

| 8. Mothers’ Educational Attainment | 0.19 *** | −0.02 | 0.15 ** | 0.15 ** | −0.06 | −0.08 | 0.09 | -- |

| Mean | 76.47 | 4.24 | 2.25 | 2.28 | 13.78 | 7.40 | 1.49 | 2.37 |

| SD | 15.52 | 0.59 | 0.39 | 0.41 | 0.71 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.89 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shi, Z.; Yang, B.; Chen, B.-B.; Chen, X.; Qu, Y. What Motivates Chinese Mothers’ Involvement in Adolescents’ Learning? Longitudinal Investigation on the Role of Mothers’ Expectations of Adolescents’ Family Obligations and Adolescents’ Academic Performance. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 632. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080632

Shi Z, Yang B, Chen B-B, Chen X, Qu Y. What Motivates Chinese Mothers’ Involvement in Adolescents’ Learning? Longitudinal Investigation on the Role of Mothers’ Expectations of Adolescents’ Family Obligations and Adolescents’ Academic Performance. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(8):632. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080632

Chicago/Turabian StyleShi, Zeyi, Beiming Yang, Bin-Bin Chen, Xiaochen Chen, and Yang Qu. 2023. "What Motivates Chinese Mothers’ Involvement in Adolescents’ Learning? Longitudinal Investigation on the Role of Mothers’ Expectations of Adolescents’ Family Obligations and Adolescents’ Academic Performance" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 8: 632. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080632

APA StyleShi, Z., Yang, B., Chen, B.-B., Chen, X., & Qu, Y. (2023). What Motivates Chinese Mothers’ Involvement in Adolescents’ Learning? Longitudinal Investigation on the Role of Mothers’ Expectations of Adolescents’ Family Obligations and Adolescents’ Academic Performance. Behavioral Sciences, 13(8), 632. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080632