The Effect of Downward Social Comparison on Creativity in Organizational Teams, with the Moderation of Narcissism and the Mediation of Negative Affect

Abstract

1. Introduction

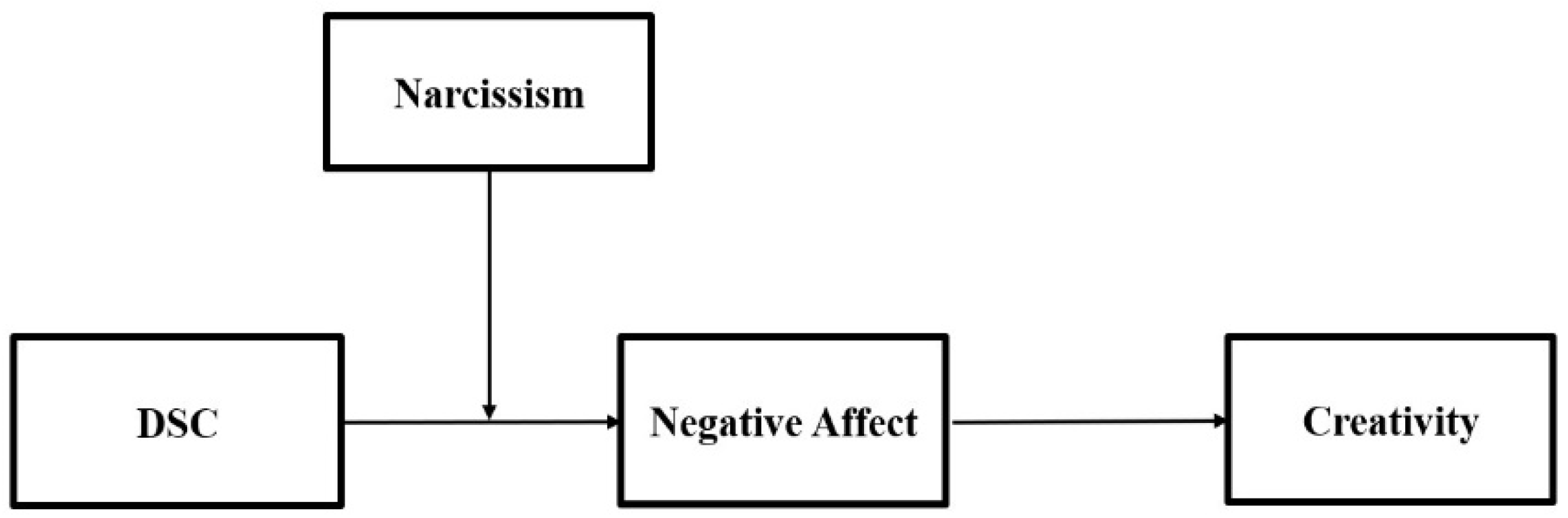

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Social Comparison Theory

2.2. Downward Social Comparison and Negative Affect

2.3. The Moderating Role of Narcissism

2.4. Negative Affect and Creativity

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedures

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Downward social comparison (DSC) of creative ability

3.2.2. Narcissism

3.2.3. Negative affect

3.2.4. Creativity

3.2.5. Control variables

4. Results

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

4.2. Correlation Analysis

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

4.3.1. Effect of downward social comparison on negative affect

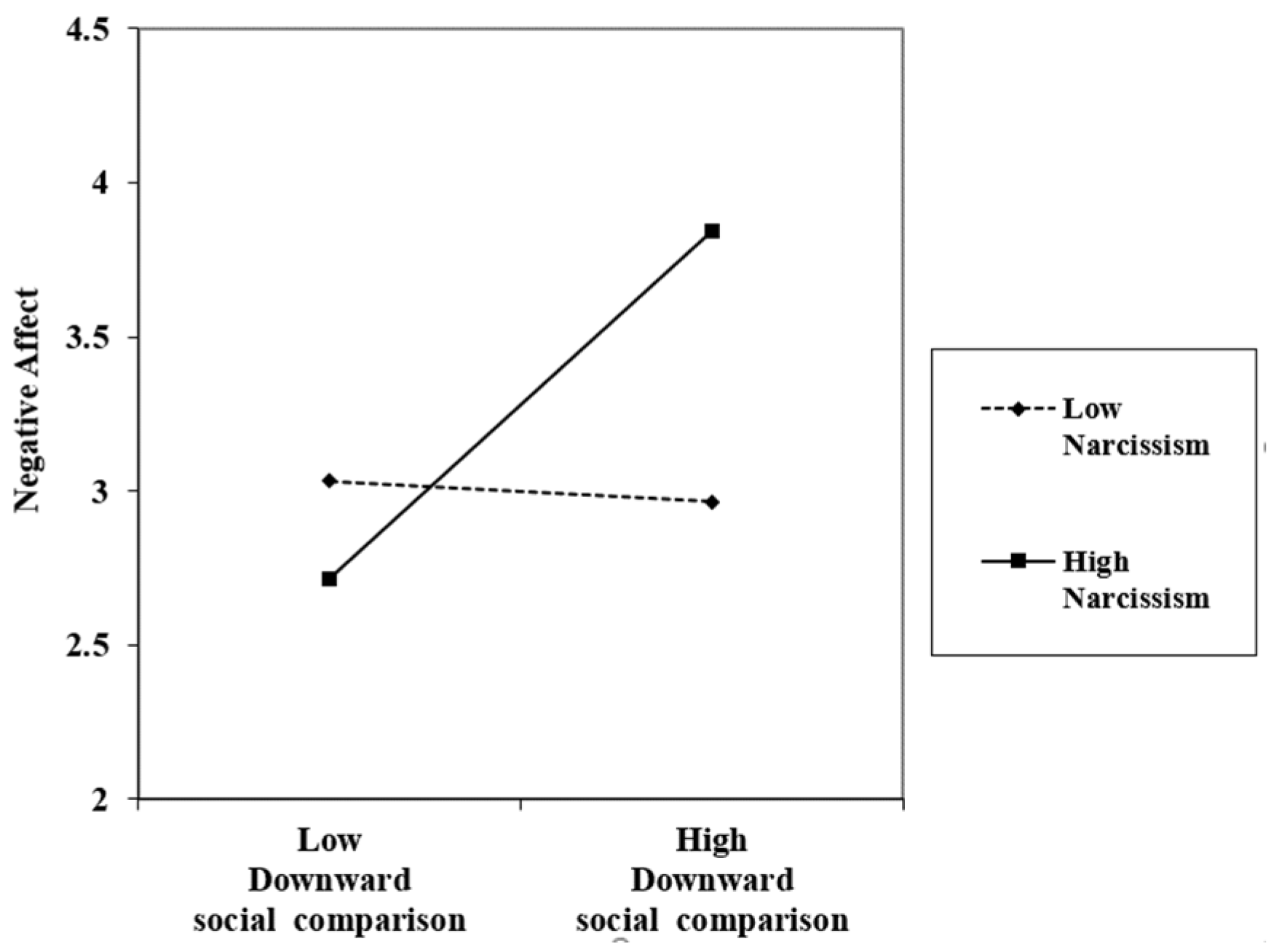

4.3.2. Moderating effect of narcissism

4.3.3. Negative affect and creativity

4.3.4. Moderated mediation by narcissism

5. Discussion

5.1. Overall Findings

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Study Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Joshi, A.; Roh, H. The role of context in work team diversity research: A meta-analytic review. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 599–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zattoni, A.; Leventis, S.; Van Ees, H.; De Masi, S. Board diversity’s antecedents and consequences: A review and research agenda. Leadersh. Q. 2022, 34, 101659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Tajpour, M.; Razavi, S.M. The effect of team performance on the internationalization of Digital Startups: The mediating role of entrepreneurship. Int. J. Hum. Cap. Urban Manag. 2023, 8, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. A theory of social comparison processes. Hum. Relat. 1954, 7, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crusius, J.; Corcoran, K.; Mussweiler, T. Social comparison: A review of theory, research, and applications. In Theories in Social Psychology, 2nd ed.; Chadee, D., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber, J.P.; Wheeler, L.; Suls, J. A social comparison theory meta-analysis 60+ years on. Psychol. Bull. 2018, 7, 177–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wills, T.A. Downward comparison principles in social psychology. Psychol. Bull. 1981, 90, 245–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buunk, B.P.; Gibbons, F.X. Toward an Enlightenment in Social Comparison Theory. In Handbook of Social Comparison: Theory and Research; Suls, J., Wheeler, L., Eds.; Springer Science Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 487–499. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.; Ding, W.; Li, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhao, M. Compared with Him or Her, I Am Not Good Enough: How to Alleviate Depression Due to Upward Social Comparison? J. Psychol. 2022, 156, 512–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.V.; Taylor, S.E.; Lichtman, R.R. Social comparison in adjustment to breast cancer. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 49, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, R.L. For better or worse: The impact of upward social comparison on self-evaluations. Psychol. Bull. 1996, 119, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zell, E.; Strickhouser, J.E. Comparisons across dimensions, people, and time: On the primacy of social comparison in self-evaluations. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 2020, 11, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P.; Price, J.; Allan, S. Social comparison, social attractiveness and evolution: How might they be related? New Ideas Psychol. 1995, 13, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crusius, J.; Lange, J. How do people respond to threatened social status? Moderators of benign versus malicious envy. In Envy at Work and in Organizations; Smith, R.H., Merlone, U., Duffy, M.K., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 85–110. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. Upward social comparison and depression in social network settings: The roles of envy and self-efficacy. Internet Res. 2019, 29, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suls, J.; Martin, R.; Wheeler, L. Social comparison: Why, with whom, and with what effect? Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2002, 11, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, S.; Hennekam, S. Constructing a positive identity as a disabled worker through social comparison: The role of stigma and disability characteristics. J. Vocat. Behav. 2021, 125, 103528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakkar Sudha, K.; Shahnawaz, M.G. Narcissism personality trait and performance: Task-oriented leadership and authoritarian styles as mediators. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2020, 41, 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazire, S.; Funder, D.C. Impulsivity and the self-defeating behavior of narcissists. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 10, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker, J.; Gallo, L. The Self-Enhancing Effect of Downward Comparison; 93rd Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Burleson, K.; Leach, C.W.; Harrington, D.M. Upward social comparison and self-concept: Inspiration and inferiority among art students in an advanced programme. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 44, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morry, M.M.; Sucharyna, T.A. Relationship social comparison interpretations and dating relationship quality, behaviors, and mood. Pers. Relatsh. 2016, 23, 554–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buunk, B.P.; Collins, R.L.; Taylor, S.E.; Vanyperen, N.W.; Dakof, G.A. The affective consequences of social comparison: Either direction has its ups and downs. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 59, 1238–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, N.; Kuhl, J. Intuition, affect, and personality: Unconscious coherence judgments and self-regulation of negative affect. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 1213–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Zee, K.; Oldersma, F.; Buunk, B.P.; Bos, D. Social comparison preferences among cancer patients as related to neuroticism and social comparison orientation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 75, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheshure, A.; Zeigler-Hill, V.; Sauls, D.; Vrabel, J.K.; Lehtman, M.J. Narcissism and emotion dysregulation: Narcissistic admiration and narcissistic rivalry have divergent associations with emotion regulation difficulties. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2020, 154, 109679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodewalt, F.; Morf, C.C. Self and interpersonal correlates of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory: A review and new findings. J. Res. Pers. 1995, 29, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogart, L.M.; Benotsch, E.G.; Pavlovic, J.D.P. Feeling superior but threatened: The relation of narcissism to social comparison. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 26, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, E.; Huang, X.; Robinson, S.L.; Ouyang, K. Loving or loathing? A power-dependency explanation for narcissists’ social acceptance in the workplace. J. Organ. Behav. 2022, 43, 783–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, P.J.; Hickman, S.E.; Morris, R.J. Self-reported narcissism and shame: Testing the defensive self-esteem and continuum hypotheses. Pers. Individ. Differ. 1996, 21, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, W.K.; Foster, C.A.; Finkel, E.J. Does self-love lead to love for others? A story of narcissistic game playing. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, A.J.; Jeschke, J.; Jordan, C.H.; Bruner, M.W.; Arnocky, S. Will they stay or will they go? Narcissistic admiration and rivalry predict ingroup affiliation and devaluation. J. Pers. 2019, 87, 871–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, W.K.; Hoffman, B.J.; Campbell, S.M.; Marchisio, G. Narcissism in organizational contexts. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2011, 21, 268–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baas, M.; De Dreu, C.K.W.; Nijstad, B.A. A meta-analysis of 25 years of mood-creativity research: Hedonic tone, activation, or regulatory focus? Psychol. Bull. 2008, 134, 779–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.M.; Zhou, J. Dual tuning in a supportive context: Joint contributions of positive mood, negative mood, and supervisory behaviors to employee creativity. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 605–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.A.; Tang, J. The role of entrepreneurs in firm-level innovation: Joint effects of positive affect, creativity, and environmental dynamism. J. Bus. Ventur. 2011, 26, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ye, Z.; Shafait, Z.; Zhu, H. The effect of abusive supervision on employee creativity: The mediating role of negative affect and moderating role of interpersonal harmony. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 796355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, J.R.; Lambert, L.S. Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brislin, R.W. The wording and translation of research instrument. In Field Methods in Cross-Cultural Research; Lonner, W.J., Berry, J.W., Eds.; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1986; pp. 137–164. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.N.; Anderson, T.A.; Veillette, A. Contextual inhibitors of employee creativity in organizations: The insulating role of creative ability. Group Organ. Manag. 2009, 34, 330–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonason, P.K.; Webster, G.D. The dirty dozen: A concise measure of the dark triad. Psychol. Assess. 2010, 22, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, P.; Bindl, U.K.; Parker, S.K.; Inceoglu, I. Four-quadrant investigation of job-related affects and behaviours. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2014, 23, 342–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madjar, N.; Greenberg, E.; Chen, Z. Factors for radical creativity, incremental creativity, and routine, noncreative performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 730–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, H.; Park, J. The effects of routinization on radical and incremental creativity: The mediating role of mental workloads. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudenbush, S.W.; Bryk, A.S. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G.; Reno, R.R. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Shalley, C.E.; Zhou, J.; Oldham, G.R. The effects of personal and contextual characteristics on creativity: Where should we go from here? J. Manag. 2004, 30, 933–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry-Smith, J.E.; Mannucci, P.V. From creativity to innovation: The social network drivers of the four phases of the idea journal. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2017, 42, 53–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodman, R.W.; Sawyer, J.E.; Griffin, R.W. Toward a theory of organizational creativity. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1993, 18, 293–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Spec. | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 18 | 13.8 |

| Male | 112 | 86.2 | |

| Age | 20 | 12 | 9.2 |

| 30 | 68 | 52.3 | |

| 40 | 45 | 34.6 | |

| Over 50 | 5 | 3.9 | |

| Education | High school graduated | 2 | 1.5 |

| College graduated | 44 | 33.8 | |

| University graduated | 31 | 23.8 | |

| Over graduate school | 53 | 40.9 | |

| Tenure | Under 5 years | 18 | 13.8 |

| 5–10 years | 29 | 22.3 | |

| 10–15 years | 42 | 32.3 | |

| 15–20 years | 21 | 16.2 | |

| Over 20 years | 20 | 15.4 | |

| Model | No. of Factors a | χ2 | df | Δχ2 | RMSEA | CFI | IFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline model | 4 factors: DSC, NA, NAR, CRE | 390.322 | 202 | 0.085 | 0.909 | 0.910 | |

| Model 1 | 3 factors: (DSC + NA), NAR, CRE | 659.200 | 205 | 268.878 ** | 0.131 | 0.780 | 0.783 |

| Model 2 | 2 factors: (DSC + NA + NAR), CRE | 1005.551 | 207 | 615.229 ** | 0.173 | 0.613 | 0.617 |

| Variable | Mean | S. D | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 37.12 | 6.15 | ||||||||

| 2. Gender | 0.42 | 0.35 | 0.16 | |||||||

| 3. Tenure | 2.82 | 74.26 | 0.83 *** | 0.18 * | ||||||

| 4. Education | 7.66 | 1.10 | −0.29 ** | −0.20 * | −0.38 *** | |||||

| 5. DSC | 4.80 | 0.65 | 0.32 *** | 0.08 | 0.22 * | −0.19 * | <0.93> | |||

| 6. Narcissism | 4.00 | 0.68 | −0.70 | −0.13 | −0.07 | 0.06 | 0.08 | <0.94> | ||

| 7. Negative affect | 4.80 | 0.71 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.01 | −0.21 * | 0.30 *** | 0.10 | <0.88> | |

| 8. Creativity | 4.80 | 0.54 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.04 | −0.15 | 0.04 | −0.23 * | <0.89> |

| Variable | Negative Affect | Creativity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | |

| Constant | 2.10 ** | 2.51 ** | 2.45 ** | 2.23 ** | 2.29 ** | 2.28 ** | 2.26 ** |

| Age | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 * |

| Gender | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.22 * | 0.21 | 0.00 |

| Tenure | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Education | −0.15 * | −0.13 * | −0.13 * | −0.11 * | 0.03 | 0.01 | -10 |

| Downward social comparison (DSC) | 0.30 * | 0.28 * | 0.25 * | −0.14 * | |||

| Narcissism (NAR) | 0.10 | 0.15 | |||||

| DSC X NAR | 0.31 * | ||||||

| Negative affect | −0.11 * | ||||||

| Pseudo R square | 0.48 | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.53 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.08 |

| Independent Variable | Mediator | Dependent Variable | Moderator | Moderator Level | Conditional Indirect Effect | Bootstrapping Bias-Corrected 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Downward Social Comparison | Negative Affect | Creativity | Narcissism | Low (Mean − 1 SD) | −0.009 | −0.077 | 0.042 |

| High (Mean + 1 SD) | −0.073 | −0.190 | −0.014 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, Y.; Chae, H. The Effect of Downward Social Comparison on Creativity in Organizational Teams, with the Moderation of Narcissism and the Mediation of Negative Affect. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 633. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080633

Yang Y, Chae H. The Effect of Downward Social Comparison on Creativity in Organizational Teams, with the Moderation of Narcissism and the Mediation of Negative Affect. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(8):633. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080633

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Yuha, and Heesun Chae. 2023. "The Effect of Downward Social Comparison on Creativity in Organizational Teams, with the Moderation of Narcissism and the Mediation of Negative Affect" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 8: 633. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080633

APA StyleYang, Y., & Chae, H. (2023). The Effect of Downward Social Comparison on Creativity in Organizational Teams, with the Moderation of Narcissism and the Mediation of Negative Affect. Behavioral Sciences, 13(8), 633. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080633