Factors Influencing Participation in Physical Activity, Sports, and Exercise in Children and Adolescents with Spinal Pain or Spinal Conditions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Ethnography

Abstract

1. Introduction

Objectives

- (a)

- To describe factors influencing participation in sports, exercise, and PA in children and adolescents aged 18 years or under with thoracic or lumbar spinal pain or diagnosed conditions;

- (b)

- To identify any trends or differences in factors influencing participation between discrete sub-populations, such as age, gender, or spinal condition.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient and Public Involvement

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Information Sources

2.4. Search Strategy

2.5. Data Management

2.6. Selection Process

2.7. Data-Collection Process

2.8. Data Items

2.9. Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

2.10. Outcomes and Prioritisation

2.11. Synthesis Methods

2.12. Reporting Bias and Trustworthiness Assessment

2.13. Certainty Assessment

3. Results

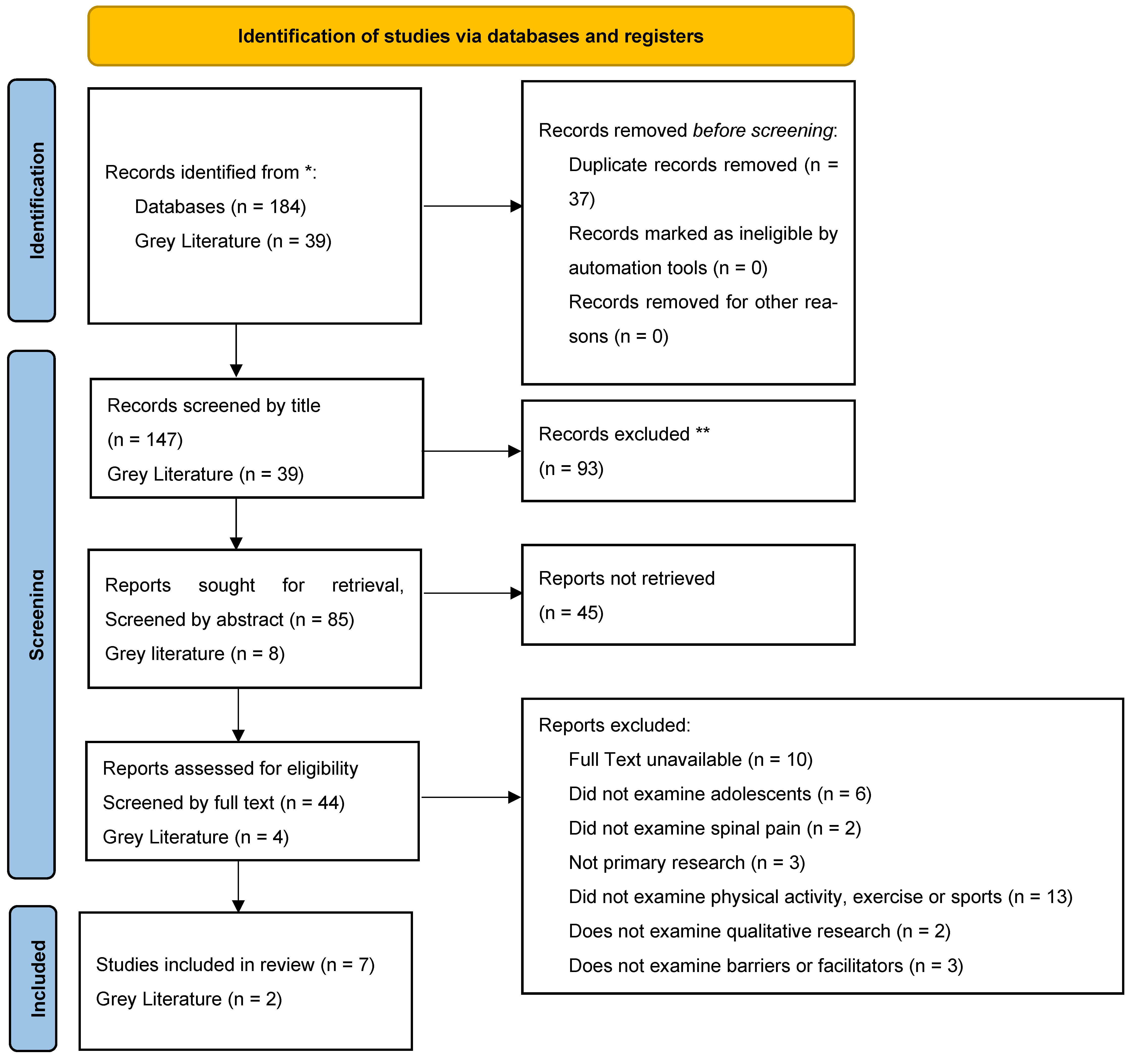

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

| Study | Participant Characteristics (n = Children, p = Parents, c = Caregivers) | Participant Gender (F n = Female Children, M n = Male Children, F p = Female Parents, M p = Male Parents, F c = Female Caregivers, M c = Male Caregivers) | Participant Age (Years) | Participant Diagnosis | Setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bloemen, et al. (2015) [24] | 4–7 years olds: n = 11 p =13 8–18 years: c = 33 p = 31 | 4–7 years olds: F n = 4 M n = 7 8–18 years olds: F n = 15 M n = 18 | n = 11 × 4 to 7 n = 33 × 8 to 18 | Spina bifida | A rehabilitation centre, a paediatric physiotherapy institution, or in the home situation in The Netherlands. |

| Gorzkowski, et al. (2011) [25] | c = 201 | F n = 52% M n = 48% | n mean age at interview = 12.60 n mean age at injury = 7.19 | Spinal-cord injury | Three paediatric spinal- cord injury centres. |

| Nahal, et al. (2019) [26] | n = 10 | F n = 4 M n = 6 | n = 7 to 18 | Spinal bifida | Participants were recruited from three main rehabilitation centres from the north (n = 3), the middle (n = 3), and the south (n = 4) of the West Bank in Palestine. |

| Page and Coetzee (2021) [27] | n = 7 | F n = 2 M n = 5 F c = 2 M c = 5 | n = 13–16 n mean age = 14.5 c = 39–75 c mean age = 49.5 | Spinal bifida | The Cape Flats, southeast of central Cape Town, South Africa. |

| Pfeiffer, et al. (2021) [28]. | n = 32 | F n = 20 M n = 12 | n = 9 to 17 n mean =13 n = 13 × 9 to 12 n = 9 × 12 to 15 n = 10 × 15 to 18 | Achondro-plasia | 16 participants from the USA, and 16 participants from Spain. |

| Volfson, et al. (2020) [29]. | n = 9 | F n = 6 M n = 3 | n = 1 × 14 n = 2 × 15 n = 3 × 16 n = 3 × 17 n mean = 15.9 | Spina bifida | Spina bifida outpatient clinic at a rehabilitation centre located in a large urban centre in Canada. |

| Willson, et al. (2021) [30]. | n = 8 | F n = 4 M n = 4 | n = 14 to 17 n mean = 15.4 | Returning to PA following spinal surgery | Unclear |

| Fischer, et al. (2015) [31]. | n = 11 10 parents | F n = 7 M n = 4 F p = 7 M p = 3 | n = 1 × 6 n = 1 × 8 n = 1 × 9 n = 3 × 10 n = 1 × 14 n = 1 × 15 n = 1 × 16 n = 1 × 17 n = 1 × 18 | Spina bifida | Spina bifida clinic at a large paediatric rehabilitation hospital in Canada. |

| Strömfors, et al. (2017) [32]. | n = 8 | F n = 4 M n = 4 | n = 1 × 10 n = 1 × 11 n = 1 × 12 n = 2 × 14 n = 1 × 15 n = 2 × 17 | Spina bifida | Swedish children and adolescents. Recruitment took place at a bowel- and bladder-functions clinic for children and adolescents with SB. Two participants completed interviews at home. Six participants completed interviews at a local health-care facility that they visited regularly. |

3.3. Study Trustworthiness

3.4. Results of Individual Studies

3.5. Results of Synthesis

3.5.1. Theme 1: Biological Factors

- Subthemes:

Subtheme 1: Challenges to PA, Sports, or Exercise Participation Resulting from Biological Aspects of Physical Condition

- Example:

‘If he wants to go to a sledge hockey camp overnight and this kind of thing for a week, that’s the kind of thing you need to have more independence with’[31].

‘… but still being aware if there is back pain… how much of it’[29].

- Uniqueness:

- CERQual Summary:

Subtheme 2: Bladder and Bowel Care and Its Impact on Participation in PA, Sports, and Exercise

- Example:

‘whenever I run [my bladder] just lets go’ (10 years, female)[31].

‘The reason that I have not told my friends, is that I see how they are now. Young people, and now I mean people my age, they are kind of, what can I say, immature, or they say certain things. They think that if a person is different, then that person is a freak or something like that. That is why I have not dared [to tell them about having SB]’ (15 years, male)[32].

‘Everything is difficult in my life. I feel tired of living with incontinence and diapers… I hate the catheterization… I wondered why children like me with spina bifida should stay alive’ (12 years, female)[26].

- Uniqueness:

- CERQual Summary:

3.5.2. Theme 2: Psychological Factors

- Subthemes:

Subtheme 3: Feelings of Struggle and Needing for Physical Assistance from Others; Desire for Independence When Participating in Sports, Exercise, and PA

- Example:

‘I would like to join a public sports club. I love swimming and playing football with other children… I am very sad… It is difficult to reach these areas… I am not allowed to participate… I prefer to stay home’ (16 years, male)[26].

- Uniqueness:

- CERQual Summary:

Subtheme 4: Children and Adolescents Perceiving Themselves as Different from Their Peers; That They Do Not Fit in due to Physical Differences Limiting Activity Participation

- Example:

‘The school took me out of my comfort zone… I became aware that I’m different from some children who stared at me and made fun of my shaky walk’ (12 years, female)[26].

- Uniqueness:

- CERQual Summary:

Subtheme 5: Emotions of Anger, Fear, or Sadness towards Limited Participation in School Activities and Social Events

- Example:

‘I would like to join a public sports club. I love swimming and playing football with other children… I am very sad… It is difficult to reach these areas… I am not allowed to participate… I prefer to stay home’. (Boy, 16)[26].

‘It sucked for a while; I was a pretty active person so the first 6–7 months kind of sucked’[80].

- Uniqueness:

- CERQual Summary:

Subtheme 6: Need to Adjust and Accept Spinal Pain or Disability and Its Influence on Participation in Sports, Exercise, and PA

- CERQual Summary:

‘I went through very many emotional rollercoasters to finally realise that I was not like every-one else and I had to accept that’ (14 years, female)[31].

- Uniqueness:

- CERQual Summary:

3.5.3. Theme 3: Sociological Factors

- Subthemes:

Subtheme 7: Fear and Worry towards Participation in Sports, Exercise and PA; Fear towards Socialising in a Sports Group and Peer Rejection

- Example:

‘Of those killing, killing kids, girls, taking girls and grabbing them and killing taking the body parts. I don’t go outside anymore. I never go outside’ (13 years, female)[27].

- Uniqueness:

- CERQual Summary:

Subtheme 8: Dependence of Child on Caregivers and Impact on Routine (Work, Family, and Time)

- Example:

‘Managing university studies alongside a serious health condition and restrictions in mobility can be a daily struggle. I will not be able to study at university, or to work and get married. I’m afraid of what will happen to me if my mother is no longer able to care for me… who will help me in this miserable life?’ (14 years, male)[26].

- Uniqueness:

- CERQual Summary:

Subtheme 9: Negative Attitudes from Others and Lack of Social Acceptance; Experiencing Ridicule and Feeling Ashamed

- Example:

‘The reason that I have not told my friends is that I see how they are now. Young people, and now I mean people my age, they are kind of, what can I say, immature, or they say certain things. They think that if a person is different, then that person is a freak, or something like that. That is why I have not dared (to tell them about having SB)’ (15 years, male)[32].

- Uniqueness:

- CERQual Summary:

Subtheme 10: Friends Providing Needed Emotional Support and Role Models

- Example:

Three participants reported ‘many close friends’, ‘weekly sleepovers with friends’, and ‘a consistent group of close friends that she spent time with every weekend’[31].

- Uniqueness:

- CERQual Summary:

Subtheme 11: Youth Dependent on Parents for Physical and Emotional Advice or Support

- Example:

‘I knew that I had to because my parents aren’t going to be there in Grade 1 and I just didn’t want everybody knowing and I didn’t want everybody to be involved in it. I’m just like okay, I’m gonna do it’ (9 years, female)[31].

- Uniqueness:

- CERQual Summary:

Subtheme 12: Lacking Information or Support from Sports Counsellors, Local Clubs or Organisations Regarding PA

- Example:

‘A lot of things you have to find out yourself… I do miss that…I think, if you’re in a hospital, we visit the hospital regularly, that there should be…more information…and listening to what the child wants and I do miss that…they ask for example ‘how is it’, ‘yes everything goes well’ he (the child) says, well he always says everything goes well…but I think…you should ask ‘what else do you want, how is it going with playing sports, do you play sports’, it is always about what school do you go to and that’s that’ (Parent, child 8–18 years, unknown gender)[24].

- Uniqueness:

- CERQual Summary:

Subtheme 13: Desire to Be Active and Increase Environmental Access

- Example:

‘Cause I don’t wanna be, like, in a wheelchair—it’s not fun to be in. Then I can do nothing, like, say (me) now I wanna go play soccer, then I can’t cause I’m in here. And then I can’t do what other children can do’ (13 years, male)[27].

- Uniqueness:

- CERQual Summary:

- Certainty of evidence

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Clinical Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. PRISMA Flow Diagram

References

- Wu, A.; March, L.; Zheng, X.; Huang, J.; Wang, X.; Zhao, J.; Blyth, F.M.; Smith, E.; Buchbinder, R.; Hoy, D. Global low back pain prevalence and years lived with disability from 1990 to 2017: Estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, G.T.; Macfarlane, G.J. Epidemiology of low back pain in children and adolescents. Arch. Dis. Child. 2005, 90, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigdal, Ø.N.; Storheim, K.; Munk Killingmo, R.; Småstuen, M.C.; Grotle, M. Characteristics of older adults with back pain associated with choice of first primary care provider: A cross-sectional analysis from the BACE-N cohort study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e053229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hébert, J.J. Spinal pain in childhood: Prevalence, trajectories, and diagnoses in children 6 to 17 years of age. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2022, 181, 1727–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coenen, P. Trajectories of Low Back Pain From Adolescence to Young Adulthood. Arthritis Care Res. 2017, 69, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, A.M.; Smith, A.J.; Straker, L.M.; Bragge, P. Thoracic spine pain in the general population: Prevalence, incidence and associated factors in children, adolescents and adults. A systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2009, 10, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, M.; Minozzi, S.; Bettany-Saltikov, J.; Zaina, F.; Chockalingam, N.; Kotwicki, T.; Maier-Hennes, A.; Negrini, S. Exercises for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 2012, CD007837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshami, A.M. Prevalence of spinal disorders and their relationships with age and gender. Saudi Med. J. 2015, 36, 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinathan, N.R.; Viswanathan, V.K.; Crawford, A.H. Cervical Spine Evaluation in Pediatric Trauma: A Review and an Update of Current Concepts. Indian J. Orthop. 2018, 52, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fares, J.; Fares, M.Y.; Fares, Y. Musculoskeletal neck pain in children and adolescents: Risk factors and complications. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2017, 8, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS. Physical Activity Guidelines for Children and Young People. 2021. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/exercise/exercise-guidelines/physical-activity-guidelines-children-and-young-people/ (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Calvo-Muñoz, I.; Gómez-Conesa, A.; Sánchez-Meca, J. Physical therapy treatments for low back pain in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2013, 14, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayden, J.A.; Ellis, J.; Ogilvie, R.; Malmivaara, A.; van Tulder, M.W. Exercise therapy for chronic low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 9, Cd009790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geneen, L.J.; Moore, R.A.; Clarke, C.; Martin, D.; Colvin, L.A.; Smith, B.H. Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: An overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 4, CD011279. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mueller, S.; Mueller, J.; Stoll, J.; Prieske, O.; Cassel, M.; Mayer, F. Incidence of back pain in adolescent athletes: A prospective study. BMC Sport. Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2016, 8, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, B.N.; Johnson, C.; Moreau, W. Is physical activity contraindicated for individuals with scoliosis? A systematic literature review. J. Chiropr. Med. 2009, 8, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frosch, M.; Leinwather, S.; Bielack, S.; Blödt, S.; Dirksen, U.; Dobe, M.; Geiger, F.; Häfner, R.; Höfel, L.; Hübner-Möhler, B.; et al. Treatment of Unspecific Back Pain in Children and Adolescents: Results of an Evidence-Based Interdisciplinary Guideline. Children 2022, 9, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gov.UK. New Physical Activity Guidelines 25 July 2011. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-physical-activity-guidelines (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- NICE. Low Back Pain and Sciatica in Cver 16s: Assessment and Management. 2016. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng59/chapter/Recommendations (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Michaleff, Z.A.; Kamper, S.J.; Maher, C.G.; Evans, R.; Broderick, C.; Henschke, N. Low back pain in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the effectiveness of conservative interventions. Eur. Spine J. 2014, 23, 2046–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motyer, G.S.; Kiely, P.J.; Fitzgerald, A. Adolescents’ Experiences of Idiopathic Scoliosis in the Presurgical Period: A Qualitative Study. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2021, 47, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrini, S.; Donzelli, S.; Aulisa, A.G.; Czaprowski, D.; Schreiber, S.; De Mauroy, J.C.; Diers, H.; Grivas, T.B.; Knott, P.; Kotwicki, T.; et al. 2016 SOSORT guidelines: Orthopaedic and rehabilitation treatment of idiopathic scoliosis during growth. Scoliosis Spinal Disord. 2018, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joergensen, A.C.; Strandberg-Larsen, K.; Andersen, P.K.; Hestbaek, L.; Andersen, A.N. Spinal pain in pre-adolescence and the relation with screen time and physical activity behavior. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2021, 22, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloemen, M.A.; Verschuren, O.; van Mechelen, C.; Borst, H.E.; de Leeuw, A.J.; van der Hoef, M.; de Groot, J.F. Personal and environmental factors to consider when aiming to improve participation in physical activity in children with Spina Bifida: A qualitative study. BMC Neurol. 2015, 15, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorzkowski, J.; Kelly, E.H.; Klaas, S.J.; Vogel, L.C. Obstacles to community participation among youth with spinal cord injury. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2011, 34, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahal, M.S.; Axelsson, A.B.; Imam, A.; Wigert, H. Palestinian children’s narratives about living with spina bifida: Stigma, vulnerability, and social exclusion. Child Care Health Dev. 2019, 45, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, D.T.; Coetzee, B.J. South African adolescents living with spina bifida: Contributors and hindrances to well-being. Disabil. Rehabil. 2021, 43, 920–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeiffer, K.M.; Brod, M.; Smith, A.; Ota, S.; Charlton, R.W.; Viuff, D. Functioning and well-being in older children and adolescents with achondroplasia: A qualitative study. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2021, 188, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volfson, Z.; Arbour-Nicitopoulos, K.P.; McPherson, A.C.; Tomasone, J.R.; Faulkner, G.E. Examining factors of physical activity participation in youth with spina bifida using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Disabil. Health J. 2020, 13, 100922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willson, L.R.; Klootwyk, M.; Rogers, L.G.; Sasseville, C.; Shearer, K.; Southon, S. Timelines for returning to physical activity following pediatric spinal surgery: Recommendations from the literature and preliminary data. BMC Res. Notes 2021, 14, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, N. A qualitative exploration of the experiences of children with spina bifida and their parents around incontinence and social participation. Child Care Health Dev. 2015, 41, 954–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strömfors, L.; Wilhelmsson, S.; Falk, L.; Höst, G.E. Experiences among children and adolescents of living with spina bifida and their visions of the future. Disabil. Rehabil. 2017, 39, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamper, S.J.; Apeldoorn, A.T.; Chiarotto, A.; Smeets, R.J.E.M.; Ostelo, R.W.J.G.; Guzman, J.; van Tulder, M.W. Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Br. Med. J. 2015, 350, h444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: Children and Youth Version: ICF-CY; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ptyushkin, P.; Vidmar, G.; Burger, H.; Marinček, Č.; Escorpizo, R. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) in vocational rehabilitation and disability assessment in Slovenia: State of law and users’ perspective. Disabil. Rehabil. 2011, 33, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, A.-W.; Yen, C.-F.; Liou, T.-H.; Bedell, G.; Granlund, M.; Teng, S.-W.; Chang, K.-H.; Chi, W.-C.; Liao, H.-F. Development and validation of the ICF-CY-Based Functioning Scale of the Disability Evaluation System—Child Version in Taiwan. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2015, 114, 1170–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanches-Ferreira, M.; Simeonsson, R.J.; Silveira-Maia, M.; Alves, S.; Tavares, A.; Pinheiro, S. Portugal’s special education law: Implementing the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health in policy and practice. Disabil. Rehabil. 2013, 35, 868–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Polo, G.; Pradal, M.; Bortolot, S.; Buffoni, M.; Martinuzzi, A. Children with disability at school: The application of ICF-CY in the Veneto region. Disabil. Rehabil. 2009, 31 (Suppl. S1), S67–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDougall, J.; Wright, V.; Schmidt, J.; Miller, L.; Lowry, K. Applying the ICF framework to study changes in quality-of-life for youth with chronic conditions. Dev. Neurorehabil. 2011, 14, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrell-Carrió, F.; Suchman, A.L.; Epstein, R.M. The biopsychosocial model 25 years later: Principles, practice, and scientific inquiry. Ann. Fam. Med. 2004, 2, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, G.L. The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science 1977, 196, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mescouto, K.; Olson, R.E.; Hodges, P.W.; Setchell, J. A critical review of the biopsychosocial model of low back pain care: Time for a new approach? Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 44, 3270–3284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.J. Encouraging healthy spine habits to prevent low back pain in children: An observational study of adherence to exercise. Physiotherapy 2016, 102, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holopainen, R.; Simpson, P.; Piirainen, A.; Karppinen, J.; Schütze, R.; Smith, A.; O’Sullivan, P.; Kent, P. Physiotherapists’ perceptions of learning and implementing a biopsychosocial intervention to treat musculoskeletal pain conditions: A systematic review and metasynthesis of qualitative studies. PAIN 2020, 161, 1150–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimiecik, J.C.; Horn, T.S.; Shurin, C.S. Relationships among Children’s Beliefs, Perceptions of Their Parents’ Beliefs, and Their Moderate-to-Vigorous Physical Activity. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 1996, 67, 324–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, S.C.; Patel, S.; Underwood, M.; Keating, J.L. What Are Patient Beliefs and Perceptions About Exercise for Nonspecific Chronic Low Back Pain? A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. Clin. J. Pain 2014, 30, 995–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, R.; Lawton, R.; Panagioti, M.; Johnson, J. Meta-ethnography in healthcare research: A guide to using a meta-ethnographic approach for literature synthesis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Stern, C.; Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Jordan, Z. What kind of systematic review should I conduct? A proposed typology and guidance for systematic reviewers in the medical and health sciences. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noblit, G.W.; Hare, R.D. Meta-Ethnography: Synthesizing Qualitative Studies; Hare, R.D., Ed.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA; London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- France, E.F.; Cunningham, M.; Ring, N.; Uny, I.; Duncan, E.A.S.; Jepson, R.G. Improving reporting of meta-ethnography: The eMERGe reporting guidance. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. ahead of print. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.E.; Ryan, A. Postpositivism in Health Professions Education Scholarship. Acad. Med. 2020, 95, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, B. Generalizability in qualitative research: Misunderstandings, opportunities and recommendations for the sport and exercise sciences. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2018, 10, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.M. The qualitative-quantitative debate: Moving from positivism and confrontation to post-positivism and reconciliation. J. Adv. Nurs. 1998, 27, 1242–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIHR. PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews. 2023. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/ (accessed on 9 February 2023).

- France, E.F.; Uny, I.; Ring, N.; Turley, R.L.; Maxwell, M.; Duncan, E.A.S.; Jepson, R.G.; Roberts, R.J.; Noyes, J. A methodological systematic review of meta-ethnography conduct to articulate the complex analytical phases. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2019, 19, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis: JBI. 2020. Available online: https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- McGowan, J.; Sampson, M.; Salzwedel, D.M.; Cogo, E.; Foerster, V.; Lefebvre, C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 75, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramer, W. Updating search strategies for systematic reviews using EndNote. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2017, 105, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, A.; Smith, D.; Booth, A. Beyond PICO: The SPIDER Tool for Qualitative Evidence Synthesis. Qual. Health Res. 2012, 22, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porritt, K.; Gomersall, J.; Lockwood, C. JBI’s Systematic Reviews: Study Selection and Critical Appraisal. Am. J. Nurs. 2014, 114, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noblit, G.; Hare, D. Meta-Ethnography: Synthesiszing Qualitative Studies; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- France, E.F.; Ring, N.; Thomas, R.; Noyes, J.; Maxwell, M.; Jepson, R. A methodological systematic review of what’s wrong with meta-ethnography reporting. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JBI. The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools for Use in JBI Systematic Reviews Checklist for Qualitative Research. Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research [Internet]. 2017. Available online: https://jbi.global/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI_Critical_Appraisal-Checklist_for_Qualitative_Research2017_0.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Hannes, K. A Comparative Analysis of Three Online Appraisal Instruments’ Ability to Assess Validity in Qualitative Research. Qual. Health Res. 2010, 20, 1736–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JBI. Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research 2020. Available online: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Lewin, S.; Booth, A.; Glenton, C.; Munthe-Kaas, H.; Rashidian, A.; Wainwright, M.; Bohren, M.A.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Colvin, C.J.; Garside, R.; et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings: Introduction to the series. Implement. Sci. 2018, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Care Quality Commission. From the Pond into the Sea: Children’s Transition to Adult Health Services [PDF]. Gallowgate. 2014. Available online: https://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/CQC_Transition%20Report.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Jarvis, S.; Richardson, G.; Flemming, K.; Fraser, L. Estimation of age of transition from paediatric to adult healthcare for young people with long term conditions using linked routinely collected healthcare data. Int. J. Popul. Data Sci. 2021, 6, 1685. [Google Scholar]

- Colver, A.; Rapley, T.; Parr, J.R.; McConachie, H.; Dovey-Pearce, G.; Couteur, A.L.; McDonagh, J.E.; Bennett, C.; Maniatopoulos, G.; Pearce, M.S.; et al. Facilitating transition of young people with long-term health conditions from children’s to adults’ healthcare services—Implications of a 5-year research programme. Clin. Med. 2020, 20, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narla, N.P.; Ratner, L.; Bastos, F.V.; Owusu, S.A.; Osei-Bonsu, A.; Russ, C.M. Paediatric to adult healthcare transition in resource-limited settings: A narrative review. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2021, 5, e001059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation. Adolescent Health. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/adolescent-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- World Health Organisation. Adolescence: A Period Needing Special Attention 2014. Available online: https://apps.who.int/adolescent/second-decade/section2/page1/recognizing-adolescence.html (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of the Child. HUMAN RIGHTS [Internet]. 1989; CHAPTER IV(27531). Available online: https://treaties.un.org/doc/Treaties/1990/09/19900902%2003-14%20AM/Ch_IV_11p.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Zimmer, L. Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts. J. Adv. Nurs. 2006, 53, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, G.; Greenhalgh, T.; Westhorp, G.; Buckingham, J.; Pawson, R. RAMESES publication standards: Realist syntheses. BMC Med. 2013, 11, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Higgins, J.P.T. Tools for assessing risk of reporting biases in studies and syntheses of studies: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vögele, C. Behavioral Medicine. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Wright, J.D., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 463–469. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, G.; Willis, C.; Shields, N. Barriers and facilitators of physical activity participation for young people and adults with childhood-onset physical disability: A mixed methods systematic review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2021, 63, 914–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.; Maldonado, I.; Peralta, M.; Santos, S. Exploring psychosocial correlates of physical activity among children and adolescents with spina bifida. Disabil. Health J. 2015, 8, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, T. The implementation of the ICF among Israeli rehabilitation centers—The case of physical therapy. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2013, 29, 536–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, E.; Gustafsson, J. Validation of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) core sets from 2001 to 2019—A scoping review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2022, 44, 3736–3748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suls, J.; Rothman, A. Evolution of the Biopsychosocial Model: Prospects and Challenges for Health Psychology. Health Psychol. 2004, 23, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mays, N.; Pope, C. Qualitative Research in Health Care: Assessing Quality in Qualitative Research. BMJ 2000, 320, 50–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, C. Conducting qualitative research in physiotherapy: A methodological example. Physiotherapy 1997, 83, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, E.A.S.; Nicol, M.M. Subtle Realism and Occupational Therapy: An Alternative Approach to Knowledge Generation and Evaluation. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2004, 67, 453–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahlin, K.B.; Lexell, J. Impact of Organized Sports on Activity, Participation, and Quality of Life in People With Neurologic Disabilities. PM R. 2015, 7, 1081–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Te Velde, S.J.; Lankhorst, K.; Zwinkels, M.; Verschuren, O.; Takken, T.; de Groot, J.; HAYS study group. Associations of sport participation with self-perception, exercise self-efficacy and quality of life among children and adolescents with a physical disability or chronic disease—A cross-sectional study. Sports Med. Open 2018, 4, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, N.; Synnot, A. Perceived barriers and facilitators to participation in physical activity for children with disability: A qualitative study. BMC Pediatr. 2016, 16, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, M.G.; García, M.J. Emotional intelligence, resilience and self-esteem in disabled and non-disabled people. Enfermería Glob. 2018, 17, 263–273. [Google Scholar]

- LoBianco, A.F.; Sheppard-Jones, K. Perceptions of disability as related to medical and social factors. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 37, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antle, B.J. Factors associated with self-worth in young people with physical disabilities. Health Soc. Work 2004, 29, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, G.A.; Shultz, I.Z.; Steel, K.; Gilpin, M.; Cathers, T. Self-Evaluation and Self-Concept of Adolescents With Physical Disabilities. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 1993, 47, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, S.E.; Steele, C.A.; Jutai, J.W.; Kalnins, I.V.; Bortolussi, J.A.; Biggar, W.D. Adolescents with physical disabilities: Some psychosocial aspects of health. J. Adolesc. Health 1996, 19, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisa Skär, R.N. Peer and adult relationships of adolescents with disabilities. J. Adolesc. 2003, 26, 635–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, A.; Angerer, P.; Weber, J.; Müller, A. The prevention of musculoskeletal complaints: Long-term effect of a work-related psychosocial coaching intervention compared to physiotherapy alone—A randomized controlled trial. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2020, 93, 877–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McManus Holroyd, A.E. Interpretive Hermeneutic Phenomenology: Clarifying Understanding. Indo-Pac. J. Phenomenol. 2007, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, S.; Bohren, M.; Rashidian, A.; Munthe-Kaas, H.; Glenton, C.; Colvin, C.J.; Garside, R.; Noyes, J.; Booth, A.; Tunçalp, Ö.; et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings—Paper 2: How to make an overall CERQual assessment of confidence and create a Summary of Qualitative Findings table. Implement. Sci. 2018, 13, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, S.; Lewin, S.; Smith, H.; Engel, M.; Fretheim, A.; Volmink, J. Conducting a meta-ethnography of qualitative literature: Lessons learnt. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample: | Studies were eligible if they included: (a) children or adolescents aged 18 years or under, (b) experiencing thoracic or (c) lumbar spinal pain, or with any diagnosed spinal condition. Studies were excluded when there was a pure focus on the experience of neck pain. |

| Phenomena of interest: | Studies had to report on the effect of thoracic or lumbar diagnosed spinal condition or spinal pain on physical function. Studies were required to include qualitative data from participants who were aiming to participate in, or who were participating in, any kind of physical functioning, PA, exercise, or sports. Studies examining participation in PA as part of physiotherapy and rehabilitation following medical interventions were included, provided factors influencing participation were examined. |

| Design: | Types of qualitative data were required for inclusion. The different types included (but not limited to): ethnography, descriptive approaches, types of phenomenology, patient narratives, case studies, types of grounded theory, and action research. Studies were included where there was a clear identification, collection, and analysis of qualitative data. |

| Evaluation: | Studies had to include qualitative factors influencing participation in exercise, sports, and PA. Qualitative interviews, field notes, open questions, or focus groups that identified data surrounding PA, exercise, or sports were also included. Studies that only contained quantitative data, or that did not identify patient experiences, beliefs, or perceptions, were excluded. |

| Research Type: | Qualitative studies and mixed-methods studies were included. Conference proceedings, abstracts only, editorials, and opinions were excluded. |

| Other: | Studies where the language was not translatable into English were excluded. Studies requiring translation had to be translated by two authors independently. Both authors had to agree that the clarity and language was clear and without substantial error. Studies where the full text was unavailable from the inter-library loan system were excluded. |

| 1 | ‘adolescen *’ OR ‘child *’ OR ‘teen *’ OR ‘youth’ OR ‘young person’ OR ‘juvenile *’ |

| 2 | ‘back’ OR ‘spinal’ OR ‘thoracic’ |

| 3 | ‘barrier *’ OR ‘facilitator *’ OR ‘reason *’ OR ‘feeling *’ OR ‘belief *’ OR ‘obstacle *’ OR ‘challenge *’ |

| 4 | ‘exercise *’ OR ‘physical activit *’ OR ‘sport *’ OR ‘physical *’ OR ‘activ *’ |

| 5 | ‘questionnaire *’ OR ‘focus group *’ OR ‘interview *’ |

| 6 | ‘participation’ OR ‘quality of life’ OR ‘QOL’ |

| 7 | ‘qualitative’ OR ‘mixed method *’ OR ‘narrative’ OR ‘grounded theory’ OR ‘phenomenology’ OR ‘ethnography’ OR ‘action research’ OR ‘case studies’ |

| 8 | 1 AND 2 AND 3 AND 4 AND 5 AND 6 AND 7 |

| Theme 1: Biological Factors | Theme 2: Psychological Factors | Theme 3: Sociological Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Challenges to PA, sports, or exercise participation resulting from biological aspects of physical condition. | Feelings of struggle and needing for physical assistance from others. Desire for independence when participating in sports, exercise, and PA. | Fear and worry towards participation in sports, exercise, and PA. Fear towards socialising in a sports group and peer rejection. |

| Bladder and bowel care and its impact on participation in PA, sports, and exercise. | Children and adolescents perceiving themselves as different from their peers, and that they do not fit in. | Dependence of child on caregivers and impact on routine (work, family, and time). |

| Emotions of anger, fear or sadness towards limited participation in school activities and social events. | Negative attitudes from others and lack of social acceptance. Experiencing ridicule and feeling ashamed. | |

| Need to adjust and accept spinal pain or disability and its influence on participation in sports, exercise, and PA. | Friends providing needed emotional support and role models. | |

| Youth dependent on parents for physical and emotional advice or support. | ||

| Lacking information or support from sports counsellors, local clubs or organisations regarding PA. | ||

| Desire to be active and increase environmental access. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tucker, S.; Heneghan, N.R.; Gardner, A.; Rushton, A.; Alamrani, S.; Soundy, A. Factors Influencing Participation in Physical Activity, Sports, and Exercise in Children and Adolescents with Spinal Pain or Spinal Conditions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Ethnography. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 486. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13060486

Tucker S, Heneghan NR, Gardner A, Rushton A, Alamrani S, Soundy A. Factors Influencing Participation in Physical Activity, Sports, and Exercise in Children and Adolescents with Spinal Pain or Spinal Conditions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Ethnography. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(6):486. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13060486

Chicago/Turabian StyleTucker, Susanna, Nicola R. Heneghan, Adrian Gardner, Alison Rushton, Samia Alamrani, and Andrew Soundy. 2023. "Factors Influencing Participation in Physical Activity, Sports, and Exercise in Children and Adolescents with Spinal Pain or Spinal Conditions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Ethnography" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 6: 486. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13060486

APA StyleTucker, S., Heneghan, N. R., Gardner, A., Rushton, A., Alamrani, S., & Soundy, A. (2023). Factors Influencing Participation in Physical Activity, Sports, and Exercise in Children and Adolescents with Spinal Pain or Spinal Conditions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Ethnography. Behavioral Sciences, 13(6), 486. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13060486