Abstract

According to the epidemiological paradox, less acculturated Latina/o youth display fewer sexual risk behaviors. A systematic review was performed on psychosocial and cultural mechanisms potentially underlying the epidemiological paradox in sexual risk behaviors of U.S. Latina/o youth across acculturation measures (between January 2000 to October 2022). Thirty-five publications (n = 35) with forty-eight analyses of underlying mechanisms met the inclusion criteria. Thirty-one results from twenty-three publications found supporting evidence that one of the five factors was an underlying mechanism in the epidemiological paradox (n = 13 parenting practices, n = 4 peer influences, n = 4 familismo values, n = 4 religiosity, n = 6 traditional gender norms) as, generally protective, mediators or moderators in the link between acculturation and sexual risk behaviors. Studies varied in the sexual risk behavior examined and measurement of acculturation, but primarily employed cross-sectional designs and recruited samples through schools. Mechanisms that enhance close ties and unity of the family, such as those of familismo values and positive parenting, reduce the likelihood of sexual risk behaviors as Latina/o youth become more acculturated. Future directions are discussed which may provide guidance for risk prevention and intervention.

1. Introduction

The United States (U.S.) is seeing unprecedented changes in the diversity of its population, particularly in national origin, ethnicity, and language use of its youth. As the largest non-White ethnic group in the U.S. [1], Latina/os comprise the largest and fastest growing minority group of children in the U.S. with an exponential growth in the last two decades across the country [2]. Disease and disability among such a large population can have major public health consequences such that issues affecting the healthy development of Latina/o children should be of national importance [3]. To support healthy development and outcomes among this population, we must understand both distinct cultural and common social influences on health, both to understand etiological processes and identify where interventions should be targeted.

1.1. Sexual Risk Behaviors among Latina/o Youth

Because Latina/o adolescents’ birth rates are the highest of any major racial/ethnic group in the U.S. [4] and their sexually transmitted infection (STI) prevalence is more than twice that of Whites [5,6,7], their sexual risk behaviors have been deemed a major public health concern [8]. Preventing or delaying the initiation of sexual risk behaviors in adolescence, therefore, can have significant public health implications. Research is needed to identify processes that influence the initiation of health risk behaviors in this developmental period, particularly among vulnerable groups, to inform efforts at preventing or changing them. Given disparities and potentially distinct influences on health risk behaviors in racial/ethnic groups, it should be valuable to focus such efforts at least in part on specific groups. Here, we focus on Latina/o adolescents’ sexual risk behaviors. We defined sexual risk behaviors as sexual behavior(s) among adolescents that place them at an increased risk for the contraction of STIs, HIV/AIDS, or unintended pregnancy, which can include, but are not limited to, age of sexual initiation, lack of condom use, and multiple partners.

1.1.1. Acculturation

Migration plays an important role in the experience of many Latino families. Processes associated with migration, such as acculturation, are important concepts for understanding Latina/o health and health risk behaviors [9,10]. Acculturation is typically associated with when an individual or a family arrived in the U.S. and occurs as a process of change in cultural patterns that results from continuous firsthand contact between people from different cultures [11,12]. As of 2013, more than half of Latina/o youth have at least one parent who was born outside the U.S. [7]. The acculturation process may contribute to challenges Latino families face including language barriers, depleted social resources, experiences of discrimination, and cultural conflicts.

Various approaches have been used to operationalize acculturation, which is a complex psychological and sociological process. One approach has been to apply psychometric scales to measure the degree of acculturation, often in multiple dimensions [13,14]. Another common approach in health research has been the use of proxy variables including English language proficiency or use, ethnic identity, cultural orientation, and generational status [15,16,17,18]. Whereas ethnic identity refers to the degree to which a person views oneself as a member of a particular ethnic group, cultural orientation refers to a person’s feelings toward and levels of engagement in a culture [19]. Generational status, a categorization term used by the U.S. Census Bureau, refers to an individual or his or her parents’ place of birth. The first-generation refers to those who are foreign born. The second-generation refers to those born in the U.S. but with at least one foreign-born parent. The third- or higher generation includes those born here with two U.S. native parents [20,21].

1.1.2. Epidemiological Paradox

Notably, acculturation to the U.S. has been deemed influential to paradoxical health outcomes among Latina/os [22]. In particular, Latina/os have been found to experience health outcomes equal to, or better, than non-Hispanic Whites despite manifesting a lower socioeconomic status that is usually associated with poorer health [23]. This paradoxical finding is especially salient among less acculturated generations of Latina/os, such as those who have recently migrated to the U.S. As migrant individuals and families acculturate to the U.S. over time and generations, their developmental and health outcomes appear to become less favorable, a phenomenon termed the Hispanic epidemiological paradox, or alternatively the immigrant health paradox [20].

1.1.3. Epidemiological Paradox in Sexual Risk Behaviors

Evidence from epidemiological paradox research has demonstrated that acculturation processes are associated with paradoxical health outcomes and behaviors [24]. In fact, first-generation Latina/o youth have been found less likely to engage in sexual risk behaviors; that is, they report a later age of first intercourse and higher condom use than their later generation peers [25]. Additionally, those with low English-speaking proficiency have reported higher condom use and fewer sexual partners [26,27]. Alternatively, higher English language use has been associated with higher incidence of STIs and unplanned pregnancies [28,29]. Research has begun to explore explanations of this paradox. In fact, early work exploring the immigrant paradox primarily focused on the biophysiological effects of the phenomenon, largely ignoring the psychosocial factors. In line with the biopsychosocial model of health and wellness [30], we propose that understanding the epidemiological paradox in sexual risk behaviors for Latina/o youth can be aided through a focus on intrapersonal and interpersonal-level psychosocial and cultural processes that have been found to change as acculturation occurs.

1.1.4. Proposed Underlying Mechanisms of the Epidemiological Paradox

Psychosocial and cultural factors may help us understand why we find paradoxical outcomes for health risk behaviors, including sexual risk behaviors. For example, social and cultural characteristics have been found to mediate these associations [31]. Moreover, influences on adolescent health risk behaviors can range from intrapersonal, to interpersonal, to broader contextual factors according to the socioecological model of human development [32]. In fact, according to studies guided by the theory of planned behaviors [33], which emphasizes the role of attitudes, subjective peer norms, and perceived behavioral control in predicting an individual’s intentions to engage in a behavior, psychosocial and cultural factors such as parenting practices and peer associations are important influences on decision-making processes which predict health behaviors [34,35]. We propose a focus on intrapersonal and interpersonal social and cultural features, which are the most proximal level of influences on behaviors and have also been examined in the majority of studies on this topic.

Social processes. A large body of work has emphasized the influence of psychosocial processes on health risk behaviors that are found across cultures and contexts. Two domains of psychosocial influences on adolescent health risk behaviors including parenting features (i.e., monitoring, involvement, and communication) and peer influences (i.e., peer norms and modeling). These parental and peer factors may underlie paradoxical findings among Latina/os by both influencing sexual risk behaviors as well as change across acculturation.

Parental influences. Parental influence encompasses a wide range of attitudes or actions (e.g., monitoring, communication) that somehow shapes or molds the child’s attitudes or behaviors. Many parenting practices may serve as protective influences against engaging in risk behaviors among youth. When adolescents perceive low levels of key parental behaviors, such as monitoring, they are more likely to engage in various health risk behaviors [36,37,38]. Additionally, parenting practices can also vary with acculturation. In fact, parenting practices, such as permissiveness, change among Latinos with each successive generation in the U.S. with an increase in proportion of permissive parents [39]. Subsequently, parenting influences may explain differences in sexual risk behaviors associated with acculturation.

Peer influences. Similarly, to parental influences, peer factors vary according to acculturation and, in turn, influence sexual risk behaviors. Peer influences appear to exert the ability to influence individual behavior among members of a group based on group norms. Specifically, peer norms, or perceiving that peers are engaging in a risk behavior, have been associated with the initiation and engagement of various health risk behaviors [40,41,42]. Moreover, Latina/o adolescents whose families were more recent migrants to the U.S. have been found to be more resistant to peer pressure than those of later generations [43]. Although important, these typical social processes of parental and peer influences do not account for the unique cultural context of Latina/o youth that may contribute to the epidemiological paradox.

Cultural processes. One hypothesis posited to explain the epidemiological paradox includes the erosion of protective cultural processes as acculturation occurs. Research suggests that certain features of the Latino culture may enhance resilience, such as familism and religiousness [44]. Specifically, the retention of some traditional cultural values appears to protect adolescents from engaging in health risk behaviors [45]. However, some cultural factors such as traditional gender norms, particularly among males, increase engagement in health risk behaviors such as violence and sexual risk behaviors [46]. It is therefore important that cultural factors from intrapersonal to interpersonal levels of influence be examined as possible underlying mechanisms of the paradox. Familism, religiosity, and traditional gender norms have been the most highly examined cultural factors in this context.

Familismo. Strong family traditions anchor the upbringing of many Latina/o children. Furthermore, the cultural value of familismo, which places focus on family as a collective unit while emphasizing family bonding, dependence, obligation, and support [47], reduces the likelihood of sexual risk behavior among Latina/o youth [10,48,49]. However, more acculturated families are less likely to hold onto values and characteristics associated with familismo [14,27,47,50]. In fact, first-generation Latinos have the highest levels of family cohesion [51].

Religiosity. Within the Latino culture, religiosity is a pervasive force, guiding attitudes, behaviors, and even social interactions for many [52,53,54,55]. Religiosity, referring to the quality or state of religious beliefs or practices, may encompass the endorsement of moral values that guide an individual’s behaviors. In fact, religiosity has a protective association with various sexual risk behaviors including delayed sexual debut and fewer sexual partners [56]. Moreover, less acculturated Latina/os use religious coping strategies more frequently than those with higher levels of acculturation [57]. This deterioration of protective religious dimensions among more acculturated Latina/os may account for the epidemiological paradox in sexual risk outcomes observed among Latina/o youth.

Traditional gender norms. Traditional gender norms among Latina/o males and females are often attached to sexual values including notions of female virginity, sexual desire, and sexual communication, as well as affect sexual behaviors [58,59]. Specifically, machismo, whereby males are expected to adhere to a heightened masculine role and have little control over sexual impulses, has been associated with unprotected sex and more sexual partners among Latino adult males [60]. On the other hand, ascribing to marianismo, a traditional aspect of the female gender role that emphasizes virtues such as purity and moral strength, has been associated with reduced sexual activity among females [61]. However, inconsistent condom use has been associated with both of these gender norms among Latina/o youth [58]. Moreover, as acculturation levels increase, Latina/o individuals replace their traditional view and practice of gender roles with those of the mainstream U.S. culture [50,62]. Overall, the influence of cultural factors on sexual behaviors across acculturation processes is complex but may help us better unravel the epidemiological paradox.

1.2. Aims

Thus far, no review has examined the influence of both social processes that cross cultural bounds and Latino cultural factors as underlying mechanisms of the epidemiological paradox for sexual risk behaviors observed among U.S. Latina/o youth. Although there is research supporting that psychosocial and cultural factors operate as underlying mechanisms of the paradox, no theories or implications have been reached to illuminate why such factors explain paradoxical findings in this area which could aid in prevention strategies. Additionally, method strategies employed in such studies including the measurements used to examine the epidemiological paradox, such as generational status, language proficiency, and ethnic identification, have not been critically reviewed in this body of research. Moreover, consensus has not been established whether some cultural factors, such as traditional gender norms, lend to resiliency or risk for sexual risk behaviors among Latina/o youth.

Thus, this systematic review will (1) synthesize findings of intrapersonal and interpersonal social (i.e., parental and peer influences) and cultural (i.e., familismo, religiosity, and traditional gender norms) factors that have been found to moderate and/or mediate the epidemiological paradox for sexual risk behaviors among U.S. Latina/o youth in that the measure of acculturation will interact significantly with the sociocultural variables to increase or decrease sexual risk outcomes; (2) critique this body of research; (3) propose future directions; and (4) draw implications from this research.

2. Method

2.1. Search Strategy

The search strategy employed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines. A search of Google Scholar, PubMed, PsychINFO, EBSCO, and reference lists of eligible papers was conducted using the following key terms: Latino adolescent sexual risk behaviors, parental influence, peer influence, generation status, acculturation, (English) language use/preference, epidemiological paradox, familismo, gender norms, marianismo, machismo, and religiosity. A sequential process of examining the title, abstract, and main text content of each article was undertaken, with exclusion of articles occurring at each stage.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Studies were selected for inclusion according to the following criteria: (1) quantitative empirical publications from peer-reviewed journals published between January 2000–October 2022 in English or Spanish; (2) at least one intrapersonal or interpersonal social (i.e., parental and peer influences) and/or cultural factor (i.e., familismo, religiosity, and traditional gender norms) was included in the analysis; (3) a measurement of the epidemiological paradox through indicators of acculturation were included in the analysis; and (4) outcomes examined were sexual risk behaviors among U.S. Latino/Hispanic youth. Interrater reliability of Cohen’s Kappa was used to assess agreement for the inclusion of studies among two coders.

3. Synthesis of Review

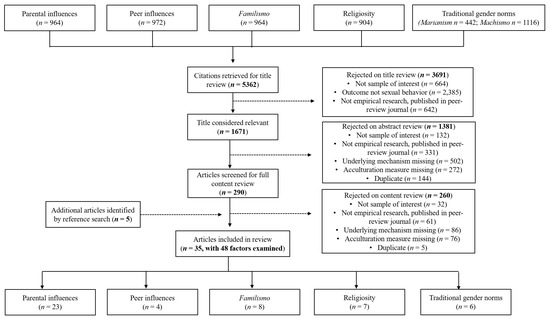

Figure 1 delineates the systematic search process. A total of 5362 citations were identified. An additional five studies were identified through reference lists. After screening of the title, abstract, and content for relevance, 5327 were excluded. Of the remaining 35 studies, which included 48 analyses of possible underlying mechanisms, 27 analyses examined social processes (n = 23 parental influences; n = 4 peer influences) and 21 examined cultural factors (n = 8 familismo; n = 7 religiosity; n = 6 traditional gender norms) as moderators or mediators of the epidemiological paradox in sexual risk outcomes among Latina/o youth. All included studies were published in English. Interrater reliability across the factors was high (κ = 0.81–0.97). Identification and coding of included studies was based on two raters for each factor. Each coder extracted information, included in Table 1, and calculated their agreement based on Cohen’s Kappa for extracted study information. About one-fourth of the included studies examined more than one factor (n = 13). The majority of the included studies (n = 30, over 85%) found significant mediating or moderating effects of sociocultural factors in sexual risk behaviors among Latina/o adolescents. Moreover, most studies that found significant effects examined two types of sexual risk behaviors: (1) use of barrier methods, and (2) initiation of sexual intercourse including intentions. Table 1 details the key characteristics and results of the included publications for each factor. Descriptions regarding the measures of acculturation used within this set of studies are provided in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Study selection flow chart. Note: Individual studies that examined multiple factors are counted as separate studies for each factor examined.

Table 1.

Summary of studies examining underlying mechanisms of epidemiological paradox findings for sexual risk behaviors among Latino youth.

Table 2.

Summary of acculturation scales used in included studies.

3.1. Parenting Influences

Summary. Twenty-three (n = 23) studies were retrieved that examined parenting practices and/or behaviors within the epidemiological paradox of Latina/o adolescent sexual risk behaviors (see Table 1). Twelve (n = 12) of the studies employed cross-sectional designs [66,68,69,70,71,72,74,75,77,78,79,85] and the other eleven employed longitudinal designs [75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85]. Sexual risk behaviors of interest varied, with four studies examining intentions to have sexual intercourse [64,68,74,75], seventeen focused on sexual activity and condom use [63,65,66,67,69,70,71,72,73,78,79,80,81,82,83,84], one on sexual partners’ risk characteristics [76], and one on knowledge about condom use [77]. Measures of acculturation were also wide-ranging, including generational and nativity status [63,64,67,70,71,72,73,74,76,82,83], acculturation discrepancies between parents and adolescents [65,79,80], language use/proficiency [63,67,69,71,73,77,78,84], and various psychometric scales of acculturation [66,68,74,75,79,80,81].

Results. Eleven studies did not support parenting practices or behaviors as an underlying mechanism between associations with acculturation and sexual risk behaviors among Latina/o youth [63,64,65,69,71,73,76,78,82,83,84,85] in that associations between acculturation, parental influences, and sexual risk behaviors were low and non-significant or parental influences were not found to be significant mediators. However, ten studies found that parenting practices had low to moderate associations with acculturation and sexual behaviors and also partially mediated associations between acculturation and specific sexual outcomes [64,66,67,68,70,71,75,79,80,81]. Additionally, two studies found that acculturation moderated associations between parenting practices and sexual behaviors [72,77].

Specifically, positive parenting practices, such as monitoring and communication, were protective against risky sexual activity in that adolescents with lower acculturation and greater positive parenting practices were approximately half as likely as those of higher acculturation and lower positive parenting behaviors to engage in sexual risk behaviors. In fact, parental acculturation also predicted adolescent sexual risk behaviors and was partially mediated by parenting practices [79]. Moreover, parental influences had an indirect effect on adolescent sexual risk behaviors through dating behaviors, such that greater acculturation among females was associated with a perceived lower maternal approval of dating which was associated with a lower likelihood of being in a relationship, which, in turn, predicted lower intentions to engage in sex in the future [68].

3.2. Peer Influences

Summary. Four studies examined peer influences as underlying mechanisms of the epidemiological paradox in Latina/o adolescent sexual risk behaviors. One employed a longitudinal design [64] and all others employed cross-sectional designs [69,75,79]. Outcomes examined included sexual behaviors by three studies [64,69,79] and sexual intentions by one study [70]. One study used language as a proxy of acculturation [69], two used nativity and/or generational status [64,75], and one used psychometric scales to measure acculturation discrepancies between parent and child [79]. Peer influences examined within the selected studies included peer pressure [69], deviant peer affiliations [75], and perceived peer sexual behavior [64,79].

Results. Three of the studies found that peer influences partially mediated associations between acculturation and sexual risk behaviors [64,75,79]. Specifically, perceived peer sexual behavior had a negative and low association to sexual risk behaviors by way of an acculturation gap between parents and adolescent children [79]. Moreover, deviant peer affiliations were a secondary mediation pathway between acculturation and sexual risk behaviors by way of parental influences. In fact, among greater acculturated Latina/o youth, lower paternal acceptance and disclosure to mothers were related to greater deviant peer affiliations, and greater deviant peer affiliations were moderately linked to greater intentions for sex [75].

3.3. Familismo

Summary. Eight studies examined values of familismo [65,66,68,76,86,87,88]. The studies were evenly split in employing cross-sectional designs [59,60,75,82] and longitudinal designs [65,76,86,88]. Sexual risk behaviors examined varied from intentions to have sexual intercourse [68], sexual activity, condom use and attitudes toward condom use [65,66,86,87,88], to sexual partners’ risk characteristics (i.e., had concurrent partners, used alcohol and/or marijuana at least weekly, and belonged to a gang or was incarcerated during their sexual relationship) [76]. Measures of acculturation were also wide-ranging, including length of time in the U.S. [88], generational and nativity status [76,86], acculturation discrepancies between parents and adolescents [65], language use [86], and various scales of acculturation [66,68,85,87].

Results. Three of the studies did not support familismo as an underlying mechanism between associations of acculturation and sexual risk behaviors among Latina/o youth [65,76,85,87] in that associations between acculturation and/or familismo or sexual outcomes were not significant. However, four studies found that familismo partially mediated associations between acculturation and some sexual behaviors by its own moderate associations with each variable [66,68,86,88]. In fact, familismo values were protective against risky sexual activity so that adolescents with higher acculturation and less familismo values were almost twice as likely as those of lower acculturation to engage in sexual risk behaviors. Moreover, familismo had an indirect effect on sexual risk behaviors through parental and peer influences, such that greater acculturation among males was associated with a lower preference of a romantic partner’s embracement of familismo, which, in turn, was associated with greater intentions to engage in sex in the future [68].

3.4. Religiosity

Summary. Seven studies examined religiosity as an explanatory mechanism [77,89,90,91,92,93,94], six of which were cross-sectional and one longitudinal [92]. Whereas five of the studies examined sexual activity and condom use [89,90,91,92,94], one examined knowledge about condom use [77], and one examined both voluntary and involuntary sexual activity as an outcome [93]. Two of the studies included religious affiliation along with a measurement of religiosity [77,92] and one examined positive religious coping [91]. Six of the studies examined some form of linguistic acculturation, one additionally included a measure of nativity [89], one included a validated measure of acculturation [91], and two included the length of time in the U.S. [91,92].

Results. Four of the studies found religiosity to be a significant and moderate mediator between acculturation and sexual risk behaviors [89,90,93,94]. Specifically, religiosity appears to fully mediate this association as a protective factor [93] in which less acculturated adolescents with higher religiosity were less likely to engage in various sexual risk behaviors [90]. However, the type of religiosity is associated with whether it is protective or risk-enhancing, such that intrinsic religiosity is protective while extrinsic increases the likelihood of engaging in risk behaviors [94].

3.5. Traditional Gender Norms

Summary. Six studies were retrieved that examined traditional gender norm values of marianismo and/or machismo [58,61,85,86,91,95]. Five were cross-sectional studies [58,61,85,91,95] and one was a retrospective longitudinal study [86]. Five of the studies examined either sexual behaviors and/or condom use, and one study examined attitudes toward condom use and intentions to use condoms in the future [85]. Two studies used validated scales of acculturation [85,91], all other studies used a measure of linguistic acculturation, and one study additionally included measurement of nativity status [86]. Various values of marianismo and machismo were examined including importance of female virginity or chastity [58,86,91,95], family pillar [91], importance of satisfying sexual needs [58], considering sexual talk disrespectful [95], and gender role orientation [61,85].

Results. All studies demonstrated support for partial mediation by gender role norms of the link between acculturation and sexual risk behaviors. Marianismo and machismo values were found to have moderate to low associations with acculturation and delayed engagement in sexual behaviors, particularly among females who regard female virginity as important [58,86,91,95]. Specifically, the lower the acculturation level and the more traditional the gender role orientation, the greater a delay in initiating sexual intercourse [61].

4. Discussion

A total of 35 publications, with 48 analyses, evaluated 1 or more of the social or cultural factors that were hypothesized to explain the epidemiological paradox in sexual risk behaviors among Latina/o youth. Thirteen of these studies examined more than one of the underlying factors of interest. Longitudinal designs were employed in 17 studies. Twenty-seven results from the thirty-five studies supported one or more of the social and cultural factors as underlying mechanisms of the epidemiological paradox, with low to moderate associations between acculturation measures, underlying mechanisms, and sexual risk behavior outcomes. The underlying mechanisms examined within these studies were generally found to be protective against engaging in sexual risk behaviors, with the exception of negative peer influences.

Yet, 18 analyses from 13 studies reported non-significant findings. Discrepant findings are likely due to the large variation in how acculturation has been measured and under-representation of several factors of interest within empirical studies, particularly of peer influences and traditional gender norms. Consequently, no firm conclusions should yet be drawn about whether some of the hypothesized underlying mechanisms explain the epidemiological paradox in Latina/o youths’ sexual risk behaviors. However, some interpretations and recommendations for future studies can be made from the current literature.

4.1. Protective Parental and Familial Explanatory Mechanisms

Of all the underlying mechanisms reviewed here, parental influences and familismo values were most often examined. Moreover, twelve studies supported parental influences and four supported familismo as underlying mechanisms of the epidemiological paradox within Latina/o youths’ sexual risk behaviors. Their protective roles in preventing sexual risk engagement may emphasize the importance of parents and families among Latina/o adolescents’ everyday life as they acculturate to U.S. norms. For example, Latina/o children are more likely than children in other racial/ethnic groups to eat dinner with their families six or seven nights a week [7]. However, Latino families are often faced with challenges including economic hardship, discrimination, and neighborhood context often characterized by high crime rates and unstable housing. These challenging contextual features along with parent–child acculturation discrepancies can also influence the parenting practices employed by Latino parents and family cohesion [103,104]. Thus, strengthening positive parenting practices and family cohesion may result in positive outcomes among Latina/o adolescents.

Mechanisms that reflect close familial ties are the most clearly supported in the literature to reduce the likelihood of sexual risk behaviors. For example, familismo values are expected to reduce the risk for negative behaviors by cementing strong bonds of attachment to the family, ensuring that the family remains a strong source of influence, and fostering conventional ties that discourage Latina/o youth from engaging in a variety of problem behaviors [62,105,106]. Moreover, family support can mitigate environmental influences such as poor neighborhood quality on health risk behaviors [107] by improving adolescent social-emotional competencies [108]. Moreover, familismo values may enhance and provide a context for parents to engage in a broader range of positive parenting practices such as monitoring, involvement, and communication. Some studies in this review examined constructs of both parental and familismo influences [65,66] within a single latent variable, possibly reflecting the overlapping role that parental and familismo mechanisms share. In fact, familismo values may ensure that parents continue to play an important role in their child’s behavior well into adolescence.

4.2. Growing Support for Additional Underlying Mechanisms

Although research on peer influences, religiosity, and traditional gender norms as underlying mechanisms is relatively small at this point, some preliminary interpretations can be made based on the limited number of studies available. Whereas there is evidence suggesting that they influence the association between acculturation and sexual risk behaviors among Latina/o adolescents, for some of these factors, it is unclear whether they are strictly protective or risk-enhancing.

Cultural factors, aside from familismo, that appear to reduce the likelihood of sexual risk behavior engagement include, among others, religiosity. When controlling for education and socioeconomic status, Latinos use religious coping mechanisms more frequently than their non-Latino White counterparts [109]. Given its prominent role in Latino culture overall, it appears probable that religiosity may be influential during difficult life transitions, such as during the immigration process [110]. Studies examining religious affiliation suggest that Latina/o adolescents who identify with Christian denominations feel that religion impacts family relationships; yet adolescents who come from families in which both parents are not present express that religion exerts a negative influence [111]. Religious values are important within traditional Latino culture and, when maintained, are likely to increase conformity, diminish involvement with delinquent peers, and inhibit participation in deviant activities [112,113]. Moreover, religiosity may enhance the protective influence of parents and family cohesion such that parents may use religion to teach values and exert social control within the family context [114]. In fact, recent research suggests that parental monitoring may mediate the relationship between family religiosity and some sexual risk behavior [115].

Alternative to parental influences and familismo values, peers can exert an influence in greater odds of an adolescent engaging in health risk behaviors including sexual behaviors [42,64,116,117]. This is particularly important during adolescence as peers increase in importance and become as or more influential than parents [118,119]. Specifically, adolescents in general are influenced by perceptions of their friends’ engagement in sexual behaviors and are more likely to engage in these behaviors to feel like they fit in [120]. Yet, adolescents who have conservative sexual attitudes engage less frequently in sexual behaviors, even if they perceive their peers to be engaging in risky sexual behaviors [121,122]. The same patterns of peer and friend impact apply to Latina/o adolescents, but with one noted difference. Latina teens are particularly influenced by cultural norms, which tend to be more conservative regarding sexuality [123]. Therefore, it can be posited that Latina early adolescents are likely to be more conservative and place greater weight on familial ties over friendship, which suggests that for these girls, peer behavior may not be as influential in their decisions to engage in sexual activities [123]. In fact, studies included in this review demonstrated that, when acculturation is taken into consideration, the weight of peer influences, although still significant, is reduced. Together, strong ties and a shared culture that opposes negative behaviors can lead to reduced negative outcomes among immigrants [31].

Gender role socialization within a Latino family context is influenced by the cultural concepts of marianismo for females and machismo for males [50]. Additionally, some facets of traditional gender norm values such as the importance of female virginity and satisfaction of sexual needs were associated with a sexual risk behavior in a protective or risk-enhancing way depending on the specific sexual behavior examined [58]. However, acculturation sways the influence of traditional gender roles on sexual risk behaviors. Specifically, among less acculturated females, values of marianismo may lend to a less assertive role within romantic relationships, which may raise concern about Latinas’ ability to communicate regarding sexuality such as condom use [95,124].

5. Methodological Critique and Limitations

This research field is relatively new and challenging. Serious methodological problems were identified in various studies. First, we found an over-representation of cross-sectional designs. Twenty-seven of the selected studies employed cross-sectional designs. However, psychosocial and cultural factors can have early and long-lasting influence on an individual’s behavior prior to the initiation of most risky behaviors [37]. Longitudinal designs should aid our understanding of early social and cultural factors that influence subsequent risk behaviors. Moreover, examining protective and risk-enhancing factors before children enter adolescence can better inform about critical periods in which interventions can be introduced prior to the initiation of most health risk behaviors.

Second, a broad variation of acculturation measurements has been used. Whereas some studies utilized language as an acculturation proxy, others have depended on nativity or generation status, and yet others relied on validated acculturation scales. However, non-uniform use of acculturation measures raises the question about whether different studies are capturing similar aspects of acculturation. Because of their reliance on unidimensional conceptions of acculturation, most studies are limited in that it is not clear whether the epidemiological paradox is due to immigrants’ acquisition of receiving-culture practices, loss of heritage–culture practices, or both [22]. In fact, some researchers argue that language use or preference measures share only small amounts of variance with more comprehensive measures and may actually capture different aspects of acculturation [125]. Alternatively, there is strong empirical evidence that supports the use of multidimensional models of acculturation over unidimensional approaches [126,127]. Some have even suggested that examining the epidemiological paradox through multidimensional constructs of acculturation may help researchers better understand underlying mechanisms of the epidemiological paradox [22]. Moreover, multidimensional constructs of acculturation should be used to examine whether biculturalism (reflecting the adoption of the receiving culture while retaining the heritage culture) [128] is the most adaptive approach to acculturation as it has been linked to better outcomes, especially among young immigrants [129,130].

Third, sample recruitment procedures evidence several limitations. Specifically, most studies relied on recruitment from educational institutions. However, due to the higher high-school drop-out rates of Latina/o in comparison to African American and White youth [131], school-based samples may not be representative of Latina/o youth across the U.S, including those at highest risk for sexual risk behaviors. Additionally, a lack of information among many studies regarding the country of origin for each study sample was notable. This is an important part of the context for understanding the results. However, the majority of studies described their sample with general terms of Hispanic or Latina/o as these populations are often treated as homogeneous. Moreover, among those that included country of origin information for their sample, most were predominantly made up of Latina/os from Mexican origins. Yet, studies have produced different results in adult samples when considering the epidemiological paradox in various health outcomes dependent on the country of origin (e.g., Puerto Rico, Mexico, Cuban) [132]. This may be due to differences in perceived discrimination, reasons for migrating, and context of reception, referring to immigrants’ opportunities in the U.S. For example, Mexicans and Puerto Ricans are more likely to be marginalized, whereas Cubans generally fare better [133]. Unlike Mexicans, many of whom are undocumented and seek “under-the-table” positions [134], and Puerto Ricans, many of whom migrate to the northeast and south to escape poverty [135], many Cubans arrive in the U.S. as political refugees (although some do immigrate to escape poverty). The effects of these differences on health risk behaviors in adolescence is not well known. Multisite studies of acculturation and health outcomes are important because acculturation may take different forms depending on the context to which individuals are acculturating [136]. This approach can also aid in capturing greater diversity in Latino group samples, which should be examined as distinct country of origin groups to determine if underlying mechanisms differ by such groups.

Finally, a lack of emphasis on gender differences was evident among some reviewed studies. Despite well-documented gender differences in sexual risk behaviors as well as possible differences in social and cultural processes, some studies did not provide separate analysis of these associations for males and females or lacked consideration for one gender (i.e., exclusive female sample). For example, girls are often more highly monitored by parents and family members than boys [137,138]. Such differences in underlying mechanisms of the epidemiological paradox may further explain differences in significant findings between gender [68,74,75,88]. Analysis of underlying mechanisms between gender would help us better understand whether there are gender differences in their influence as a protective or risk factor and therefore develop better interventions specific to each gender.

6. Future Directions

This review suggests several important future directions in this research field. First, additional studies are required to clarify the role of each social and cultural mechanism within the epidemiological paradox of Latina/o adolescent sexual risk behaviors. Specifically, much of the current literature has focused on adult populations or other health risk behaviors among adolescents, particularly substance use. Future studies should streamline the use of acculturation measures, with a preference for multidimensional constructs of acculturation measured by psychometric scales. Subsequently, with improved methodological use of acculturation measurements and further uniformity on the operationalization of psychosocial and cultural factors, meta-analytic techniques should be employed to calculate the overall effect size of these associations.

Pubertal development plays a pivotal role in an adolescent’s sexual risk behavior engagement [139]. Moreover, how and when parents discuss puberty and development with their children may influence how adolescents subsequently handle decisions of sexual behavior [140]. Such discussions may be themselves influenced by acculturation. Moreover, whether parents even discuss puberty with both boys and girls is questionable [141]. In addition, parents’ timing (i.e., before the initiation of sexual behaviors) and the content of pubertal development discussions with their children are important aspects to sexual communication [140]. Therefore, a better understanding is needed of how acculturation can influence parents’ approach and timing to discussions of pubertal development and sexual behaviors with their children and whether this differs between genders.

Decision-making is also an important aspect of engaging in risky behaviors. For example, the theory of planned behavior [33] posits that sexual behaviors involve cognitive processes by which an individual takes a step in deciding whether or not to act on a behavior. In fact, an adolescent’s intentions have been found to be highly associated with whether they will engage in a behavior or not [142,143]. Moreover, psychosocial and cultural factors appear to exert influence on the decision-making process of adolescents’ sexual behaviors across acculturation status [68,74,75]. However, it is unclear why intentions may differ across acculturation levels and how this may be influenced by social and cultural factors. Future studies should expand our understanding of social-cultural mechanisms within cognitive processes of sexual decision-making. Although some of the studies included in this review examined intentions to engage in sex as an outcome, this should be further expanded to examine the factors that influence differences in these intentions across acculturation.

For many Latino families, migration may be a fluid, unexpected, and even temporary experience. The length and timing of migration for Latinos can differ greatly. It is also important to note that in today’s political climate, deportation back to the country of origin can become a reality for both parents and children. Despite being largely ignored within the forced migration literature, it has been argued that deportation is a form of forced migration that warrants attention [144]. The stress of migration processes and fear of deportation may further influence risky behaviors, as seen among Latina/o adults’ drug use, HIV testing, and HIV prevalence in Mexico [145,146]. These stressors may also influence how parents approach their parenting strategies as well as family cohesion [108]. In fact, parenting practices partially mediated the relation between mothers’ age at arrival and young children’s social development, particularly in the case of mothers who arrived as adults [147]. Future studies should examine the role of, not just acculturation, but the migration process undertaken by Latino families when examining the epidemiological paradox. Because features of the migration are shared across groups migrating from different nations, these associations can possibly be examined among various migrant groups.

This field currently lacks a comprehensive model or theory which incorporates the role of acculturation as well as social and cultural factors to explain sexual behaviors of Latina/o youth. Some studies may use previously established models and theories to guide research examining the epidemiological paradox. However, this phenomenon is unique due to the nuanced influence of acculturation on health outcomes and its interaction with sociocultural processes, as well as its specific application to certain ethnic minority groups. Moreover, it is difficult to understand whether and how each underlying mechanism may interact with one another. Although work in this field is still growing, current findings may help the development of a theoretical model that is aimed at explaining the epidemiological paradox in health risk behaviors. Future research should have, as one aim, to support the development of a comprehensive model that accounts for both social and cultural factors across various levels of contexts within an ecological framework. Such a model would piece together the role of each social and cultural factor as well as their interaction with one another within the epidemiological paradox. Moreover, a multilevel model that accounts for broader contexts may help us understand the role of other factors, from cognitive processes to neighborhood characteristics, within the epidemiological paradox.

7. Implications

This review points to several important considerations for interventions aimed at reducing sexual risk behaviors among adolescents as well as informs policymakers and health care providers. These findings imply that behavioral public health interventions to prevent engagement in sexual risk behaviors among both U.S.-born and foreign-born Latina/os may need to attend to multiple social-ecological processes, including family and peers, as well as cultural factors uniquely common within this community. Specifically, the integration of parent and family roles in interventions and an emphasis on their involvement in adolescents’ development and maintenance of cultural values may decrease differences in sexual risk behaviors across acculturation, particularly those at increased risk from high acculturation backgrounds. Such integration of typical cross-cultural parenting practices with Latino culturally specific values may also help adolescents develop strategies to resist peer pressure and negative neighborhood influences to which Latino families are often exposed.

Moreover, awareness of the role of acculturation and sociocultural mechanisms within Latino health and health behaviors may provide a culturally sensitive guideline for health care providers. For example, acknowledging that differences in parenting practices and cultural values differ based on acculturation, as indicated by language use, nativity, or generational status, can enhance patient–provider interpersonal interactions and better address cultural-specific beliefs that may influence health outcomes. A clearer understanding of the epidemiological paradox and the underlying sociocultural mechanisms may also provide awareness among policymakers. Policies focused on sex education in public schools may need to address cultural values prominent in different groups.

8. Conclusions

This systematic review is the first, to our knowledge, that has examined the social and cultural underlying mechanisms of the epidemiological paradox in sexual risk behaviors among Latina/o youth. This systematic review, covering research published over 20 years (January 2000–October 2022), examined social and cultural mechanisms that were moderators and/or mediators of the epidemiological paradox of Latina/o adolescents’ sexual risk behaviors. The Latino community comprises complex social and cultural factors at the individual, family, community, and societal levels that are critical when addressing adolescent sexual health needs. Latina/o adolescent sexual health is a growing field of research with multiple challenges that need to be addressed. This emerging research field provides contradictory evidence that does not yet clarify the explanatory mechanisms of the epidemiological paradox. Yet, the growing evidence suggests that social and cultural factors that vary by acculturation levels are nuanced predictors of sexual behaviors among Latina/o youth. As more evidence is accumulated, such findings may provide culturally sensitive and relevant intervention guidelines for reducing the high rates of sexual risk behaviors among this population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, coding, data extraction, writing—original draft preparation, review and editing, P.C.; Literature search, data curation and data coding, writing–editing, M.C. (Miya Chinn), J.M., M.C. (Miari Costarelli), E.R., E.H., L.S. (Lily Steck), A.J.K.W., Y.B.L., S.F., G.F., L.G., L.S. (Lucia Sato), Y.P. and D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- U.S. Census Bureau. QuickFacts: 2020 Population Estimates; 2020. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/RHI725221 (accessed on 13 June 2021).

- Murphey, D.; Guzman, L.; Torres, A. America’s Hispanic Children: Gaining Ground, Looking Forward (Technical Report 2014-38). Publication# 2014-38; Child Trends: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED561392 (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Iannotta, J.G. (Ed.) Emerging Issues in Hispanic Health: Summary of a Workshop; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J.A.; Hamilton, B.E.; Osterman, M.J.K.; Curtin, S.C.; Mathews, T.J. Births: Final data for 2013. Natl. Vital Stat. Rep. 2015, 64, 1–65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance ̶ United States, 2013. MMWR 2014, 63, 1–168. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2014; Department of Health and Human Services: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moilanen, K.L.; Leary, J.M.; Watson, S.M.; Ottley, J. Predicting age of sexual initiation: Family-level antecedents in three ethnic groups. J. Early Adolesc. 2018, 38, 28–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, M.A.; Brindis, C.D.; Ralph, L.; Santelli, J. The sexual and reproductive health of young Latino males living in the United States. In Health Issues in Latino Males; Aguirre-Molina, M., Borrell, L.N., Vega, W., Eds.; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 83–98. [Google Scholar]

- Afable-Munsuz, A.; Brindis, C.D. Acculturation and the sexual and reproductive health of Latino youth in the United States: A literature review. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2006, 38, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, D.; Thing, J.P.; Baezconde Garbanati, L.; Schwartz, S.J.; Soto, D.W.; Unger, J.B. Cultural measures associated with sexual risk behaviors among Latino youth in Southern California: A longitudinal study. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2014, 46, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redfield, R.; Linton, R.; Herskovits, M.J. Memorandum for the study of acculturation. Am. Anthropol. 1936, 38, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J.W. Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 46, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, G.; Gamba, R.J. A new measurement of acculturation for Hispanics: The Bidimensional Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (BAS). Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 1996, 18, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuéllar, I.; Arnold, B.; Maldonado, R. Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans–II: A revision of the original ARSMA scale. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 1995, 17, 275–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraido-Lanza, A.F.; Chao, M.T.; Florez, K.R. Do healthy behaviors decline with greater acculturation? Implications for the Latino mortality paradox. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 61, 1243–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L.; Hofsess, L. Acculturation. In Handbook of Immigrant Health; Loue, S., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 37–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, L.M.; Schneider, S.; Comer, B. Should “acculturation” be a variable in health research? A critical review of research on US Hispanics. Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 59, 973–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salant, T.; Lauderdale, D.S. Measuring culture: A critical review of acculturation and health in Asian immigrant populations. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 57, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.L.; Chentsova-Dutton, Y.; Wong, Y. Why and how researchers should study ethnic identity, acculturation, and cultural orientation. In Asian American Psychology: The Science of Lives in Context; Nagayama Hall, G.C., Okazaki, S., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; pp. 41–65. [Google Scholar]

- Coll, C.G.E.; Marks, A.K.E. The Immigrant Paradox in Children and Adolescents: Is Becoming American a Developmental Risk? American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Foreign Born. 2013. Available online: https://www.census.gov/topics/population/foreign-born/about.html (accessed on 3 February 2016).

- Schwartz, S.J.; Unger, J.B.; Zamboanga, B.L.; Szapocznik, J. Rethinking the concept of acculturation: Implications for theory and research. Am. Psychol. 2010, 65, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzini, L.; Ribble, J.C.; Keddie, A.M. Understanding the Hispanic paradox. Ethn. Dis. 2001, 11, 496–518. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Weiss, U.K.; Tillman, K.H. Risky sexual behaviors among Hispanic young adults in South Florida: Nativity, age at immigration and gender differences. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2009, 41, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarini, T.E.; Marks, A.K.; Patton, F.; Coll, C.G. The immigrant paradox in sexual risk behavior among Latino adolescents: Impact of immigrant generation and gender. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2011, 15, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarracin, J.; Plambeck, C.R. Demographic factors and sexist beliefs as predictors of condom use among Latinos in the USA. AIDS Care 2010, 22, 1021–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marín, G. Influence of acculturation on familialism and self-identification among Hispanics. In Ethnic Identity: Formation and Transmission among Hispanics and Other Minorities; Bernal, M.E., Knight, G.P., Eds.; State University of New York Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 181–196. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, K.; Norris, A.E. Urban Hispanic adolescents and young adults: Relationship of acculturation to sexual behaviors. J. Sex Res. 1993, 30, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gindi, R.M.; Erbelding, E.J.; Page, K.R. Sexually transmitted infection prevalence and behavioral risk factors among Latino and non-Latino patients attending the Baltimore City STD clinics. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2010, 37, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, G.L. The biopsychosocial model and the education of health professionals. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 1979, 1, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, E.M.; Benson, M.L. Immigration and intimate partner violence: Exploring the immigrant paradox. Soc. Probl. 2010, 57, 480–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beadnell, B.; Wilsdon, A.; Wells, E.A.; Morison, D.M.; Gillmore, M.R.; Hoppe, M. Intrapersonal and Interpersonal Factors Influencing Adolescent’’ Decisions About Having Sex: A Test of Sufficiency of the Theory of Planned Behavior 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 37, 2840–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katherine Hutchinson, M.; Wood, E.B. Reconceptualizing adolescent sexual risk in a parent-based expansion of the theory of planned behavior. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2007, 39, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adolph, C.; Ramos, D.E.; Linton, K.L.; Grimes, D.A. Pregnanc among Hispanic teenagers: Is good parental communication a deterrent? Contraception 1995, 51, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roche, K.M.; Ahmed, S.; Blum, R.W. Enduring consequences of parenting for risk behaviors from adolescence into early adulthood. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 66, 2023–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieverding, J.A.; Adler, N.; Witt, S.; Ellen, J. The influence of parental monitoring on adolescent sexual initiation. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2005, 159, 724–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, A.K.; Russell, S.T.; Crockett, L.J. Parenting styles and youth well-being across immigrant generations. J. Fam. Issues 2007, 29, 185–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinstein, M.J.; Boergers, J.; Spirito, A. Adolescents’ and their friends’ health-risk behavior: Factors that alter or add to peer influence. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2001, 26, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, A.A.; Stanton, B.; Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Galbraith, J.; Cottrell, L.; Burns, J. Relative influences of perceived parental monitoring and perceived peer involvement on adolescent risk behaviors: An analysis of six cross-sectional data sets. J. Adolesc. Health 2003, 33, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieving, R.E.; Eisenberg, M.E.; Pettingell, S.; Skay, C. Friend’’ influence on adolescent’’ first sexual intercourse. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2006, 38, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umaña-Taylor, A.J.; Bámaca-Gómez, M.Y. Generational differences in resistance to peer pressure among Mexican-origin adolescents. Youth Soc. 2003, 35, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, G.; Marin, B.V. Research with Hispanic Populations; Sage Publications, Inc.: Southend Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Dillon, F.R.; De La Rosa, M.; Sastre, F.; Ibañez, G. Alcohol misuse among recent Latino immigrants: The protective role of preimmigration familismo. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2013, 27, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, B.V.; Gómez, C.A.; Tschann, J.M.; Gregorich, S.E. Condom use in unmarried Latino men: A test of cultural constructs. Health Psychol. 1997, 16, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabogal, F.; Marín, G.; Otero-Sabogal, R.; Marín, B.V.; Perez-Stable, E.J. Hispani? Familism and acculturation: What changes and what does’’t? Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 1987, 9, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lescano, C.M.; Brown, L.K.; Raffaelli, M.; Lima, L.A. Cultural factors and family-based HIV prevention intervention for Latino youth. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2009, 34, 1041–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velez-Pastrana, M.C.; Gonzalez-Rodriguez, R.A.; Borges-Hernández, A. Family functioning and early onset of sexual intercourse in Latino adolescents. Adolescence 2005, 40, 777. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, L. Derecho u Obligación? Parent’’ and youth’’ understanding of parental legitimacy in a Mexican origin familial context. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2007, 29, 192–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Natsuaki, M.N.; Chen, C.N. The importance of family factors and generation status: Mental health service use among Latino and Asian Americans. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2013, 19, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraido-Lanza, A.F.; Vasquez, E.; Echeverria, S.E. En las Manos de Dios [in God’s Hands]: Religious and other forms of coping among Latinos with arthritis. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2004, 72, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitchett, G.; Murphy, P.E.; Kravitz, H.M.; Everson-Rose, S.A.; Krause, N.M.; Powell, L.H. Racial/ethnic differences in religious involvement in a multi-ethnic cohort of midlife women. J. Sci. Study Relig. 2007, 46, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaña, A.; Clark, N.M. Examining a paradox: Does religiosity contribute to positive birth outcomes in Mexican American populations. Health Educ. Behav. 1995, 22, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plante, T.G.; Maunel, G.; Menendez, A.; Marcotte, D. Coping with stress among Salvadoran immigrants. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 1995, 17, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, L.M.; Haglund, K.; Fehring, R.J.; Pruszynski, J. Religiosity and sexual risk behaviors among Latina adolescents: Trends from 1995 to 2008. J. Women’s Health 2011, 20, 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mausbach, B.T.; Coon, D.W.; Cardenas, V.; Thompson, L.W. Religious coping among Caucasian and Latina dementia caregivers. J. Ment. Health Aging 2003, 9, 97–100. [Google Scholar]

- Deardorff, J.; Tschann, J.M.; Flores, E.; Ozer, E.J. Sexual values and risky sexual behaviors among Latino youths. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2010, 42, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarruel, A.M. Cultural influences on the sexual attitudes, beliefs, and norms of young Latina adolescents. J. Soc. Pediatr. Nurses 1998, 3, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolezal, C.; Carballo-Diéguez, A.; Nieves-Rosa, L.; Díaz, F. Substance use and sexual risk behavior: Understanding their association among four ethnic groups of Latino men who have sex with men. J. Subst. Abus. 2000, 11, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, C.P.; Erickson, P.I.; Juarez-Reyes, M. Acculturation, gender role orientation, and reproductive risk-taking behavior among Latina adolescent family planning clients. J. Adolesc. Res. 2002, 17, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keefe, S.; Padilla, A.; Carlos, M. The Mexican-American extended family as an emotional support system. Hum. Organ. 1979, 38, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bámaca-Colbert, M.Y.; Greene, K.M.; Killoren, S.E.; Noah, A.J. Contextual and developmental predictors of sexual initiation timing among Mexican-origin girls. Dev. Psychol. 2014, 50, 23–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, P.; Wallander, J.L.; Song, A.V.; Elliott, M.N.; Tortolero, S.R.; Reisner, S.L.; Schuster, M.A. Generational status and social factors predicting initiation of partnered sexual activity among Latino/a youth. Health Psychol. 2017, 36, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, M.Á.; Schwartz, S.J.; Castillo, L.G.; Unger, J.B.; Huang, S.; Zamboanga, B.L.; Szapocznik, J. Health risk behaviors and depressive symptoms among Hispanic adolescents: Examining acculturation discrepancies and family functioning. J. Fam. Psychol. 2016, 30, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordova, D.; Huang, S.; Lally, M.; Estrada, Y.; Prado, G. Do parent–adolescent discrepancies in family functioning increase the risk of Hispanic adolescent HIV risk behaviors? Fam. Process 2014, 53, 348–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deutsch, A.R.; Crockett, L.J. Gender, generational status, and parent-adolescent sexual communication: Implications for Latino/a adolescent sexual behavior. J. Res. Adolesc. 2016, 26, 300–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilamo-Ramos, V.; Bouris, A.; Jaccard, J.; Lesesne, C.A.; Gonzalez, B.; Kalogerogiannis, K. Family mediators of acculturation and adolescent sexual behavior among Latino youth. J. Prim. Prev. 2009, 30, 395–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, B.L.; Stritto, M.E.D. The role of socio-psychological determinants in the sexual behaviors of Latina early adolescents. Sex Roles 2012, 66, 776–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussey, J.M.; Hallfors, D.D.; Waller, M.W.; Iritani, B.J.; Halpern, C.T.; Bauer, D.J. Sexual behavior and drug use among Asian and Latino adolescents: Association with immigrant status. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2007, 9, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, J.; Potts, M.K.; Jimenez, D.R. Reproductive attitudes and behavior among Latina adolescents. J. Ethn. Cult. Divers. Soc. Work 2002, 11, 221–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karoly, H.C.; Callahan, T.; Schmiege, S.J.; Ewing, S.W.F. Evaluating the Hispanic Paradox in the context of adolescent risky sexual behavior: The role of parent monitoring. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2015, 41, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killoren, S.E.; Deutsch, A.R. A longitudinal examination of parenting processes and Latino youth’s risky sexual behaviors. J. Youth Adolesc. 2014, 43, 1982–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killoren, S.E.; Updegraff, K.A.; Christopher, F.S. Family and cultural correlates of Mexican-origin youths’ sexual intentions. J. Youth Adolesc. 2011, 40, 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killoren, S.E.; Updegraff, K.A.; Christopher, F.S.; Umaña-Taylor, A.J. Mothers, fathers, peers, and Mexican-Origin adolescents’ sexual intentions. J. Marriage Fam. 2011, 73, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minnis, A.M.; Doherty, I.; Cheng, H.; Otero-Sabogal, R.; Padian, N.S. Immigration and sexual partner risk among Latino adolescents in San Francisco. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2010, 12, 900–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, E.; Romo, L.F.; Sigman, M. Knowledge about condoms among low-income pregnant Latina adolescents in relation to explicit maternal discussion of contraceptives. J. Adolesc. Health 2006, 39, 119.e9–119.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasch, L.A.; Deardorff, J.; Tschann, J.M.; Flores, E.; Penilla, C.; Pantoja, P. Acculturation, parent-adolescent conflict, and adolescent adjustment in Mexican American families. Fam. Process 2006, 45, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prado, G.; Huang, S.; Maldonado-Molina, M.; Bandiera, F.; Schwartz, S.J.; de la Vega, P.; Pantin, H. An empirical test of ecodevelopmental theory in predicting HIV risk behaviors among Hispanic youth. Health Educ. Behav. 2010, 37, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.J.; Unger, J.B.; Des Rosiers, S.E.; Huang, S.; Baezconde-Garbanati, L.; Lorenzo-Blanco, E.I.; Szapocznik, J. Substance use and sexual behavior among recent Hispanic immigrant adolescents: Effects of parent–adolescent differential acculturation and communication. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012, 125, S26–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.J.; Des Rosiers, S.; Huang, S.; Zamboanga, B.L.; Unger, J.B.; Knight, G.P.; Szapocznik, J. Developmental trajectories of acculturation in Hispanic adolescents: Associations with family functioning and adolescent risk behavior. Child Dev. 2013, 84, 1355–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trejos-Castillo, E.; Vazsonyi, A.T. Risky sexual behaviors in first and second generation Hispanic immigrant youth. J. Youth Adolesc. 2009, 38, 719–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschann, J.M.; Flores, E.; Marin, B.V.; Pasch, L.A.; Baisch, E.M.; Wibbelsman, C.J. Interparental conflict and risk behaviors among Mexican American adolescents: A cognitive-emotional model. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2002, 30, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upchurch, D.M.; Aneshensel, C.S.; Mudgal, J.; McNeely, C.S. Sociocultural contexts of time to first sex among Hispanic adolescents. J. Marriage Fam. 2001, 63, 1158–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velazquez, E.; Corona, R.; Easter, R.; Barinas, J.; Elshaer, L.; Halfond, R.W. Cultural values, mother–adolescent discussions about sex, and Latina/o adolescents’ condom use attitudes and intentions. J. Lat. Psychol. 2017, 5, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Hernández, G.; Bamaca-Colbert, M.Y.; Vasilenko, S.A.; Mirzoeff, C.A. Timing of sexual behaviors among female adolescents of Mexican-origin: The role of cultural variables. Child Stud. Asia-Pac. Context. 2013, 3, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Guilamo-Ramos, V.; Bouris, A.; Jaccard, J.; Lesesne, C.; Ballan, M. Familial and cultural influences on sexual risk behaviors among Mexican, Puerto Rican, and Dominican youth. AIDS Educ. Prev. 2009, 21 (Suppl. B), 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, S.J.; Unger, J.B.; Des Rosiers, S.E.; Lorenzo-Blanco, E.I.; Zamboanga, B.L.; Huang, S.; Szapocznik, J. Domains of acculturation and their effects on substance use and sexual behavior in recent Hispanic immigrant adolescents. Prev. Sci. 2014, 15, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, M.B.; McGuire, J.K.; Walsh, M.; Basta, J.; LeCroy, C. Acculturation as a predictor of the onset of sexual intercourse among Hispanic and White teens. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2005, 159, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, L.M.; Fehring, R.J.; Jarrett, K.M.; Haglund, K.A. The influence of religiosity, gender, and language preference acculturation on sexual activity among Latino/a adolescents. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2008, 30, 447–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertl, M.M.; Dillon, F.R.; Cabrera Tineo, Y.A.; Verile, M.; Jurkowski, J.M.; De La Rosa, M. Sexual risk during initial months in US among Latina young adults. AIDS Care 2018, 30, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilamo-Ramos, V.; Jaccard, J.; Pena, J.; Goldberg, V. Acculturation-related variables, sexual initiation, and subsequent sexual behavior among Puerto Rican, Mexican, and Cuban youth. Health Psychol. 2005, 24, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffaelli, M.; Zamboanga, B.L.; Carlo, G. Acculturation status and sexuality among female Cuban American college students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2005, 54, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.J. Risky sexual behavior among young adult Latinas: Are acculturation and religiosity protective? J. Sex Res. 2015, 52, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deardorff, J.; Tschann, J.M.; Flores, E.; de Groat, C.L.; Steinberg, J.R.; Ozer, E.J. Latino youths’ sexual values and condom negotiation strategies. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2013, 45, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Suarez-Morales, L.; Schwartz, S.J.; Szapocznik, J. Some evidence for multidimensional biculturalism: Confirmatory factor analysis and measurement invariance analysis on the Bicultural Involvement Questionnaire-Short Version. Psychol. Assess. 2009, 21, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birman, D. Biculturalism and perceived competence of Latino immigrant adolescents. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1998, 26, 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marin, G.; Sabogal, F.; Marin, B.V.; Otero-Sabogal, R.; Perez-Stable, E.J. Development of a short acculturation scale for Hispanics. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 1987, 9, 183–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barona, A.; Miller, J.A. Short acculturation scale for Hispanic youth (SASH-Y): A preliminary report. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 1994, 16, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szapocznik, J.; Kurtines, W.M.; Fernandez, T. Bicultural involvement and adjustment in Hispanic-American youths. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 1980, 4, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phinney, J.S. The multigroup ethnic identity measure a new scale for use with diverse groups. J. Adolesc. Res. 1992, 7, 156–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, M. Development and validation of the Stephenson Multigroup Acculturation Scale (SMAS). Psychol. Assess. 2000, 12, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayón, C.; Williams, L.R.; Marsiglia, F.F.; Ayers, S.; Kiehne, E. A latent profile analysis of Latino parenting: The infusion of cultural values on family conflict. Fam. Soc. J. Contemp. Soc. Serv. 2015, 96, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varela, R.E.; Vernberg, E.M.; Sanchez-Sosa, J.J.; Riveros, A.; Mitchell, M.; Mashunkashey, J. Parenting style of Mexican, Mexican American, and Caucasian-non-Hispanic families: Social context and cultural influences. J. Fam. Psychol. 2004, 18, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, A.J.; Stuewig, J.; LeCroy, C.W. A family based model of Hispanic adolescent substance use. J. Drug Educ. 1998, 28, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, N.A.; Germán, M.; Kim, S.Y.; George, P.; Fabrett, F.C.; Millsap, R.; Dumka, L.E. Mexican American adolescents’ cultural orientation, externalizing behavior and academic engagement: The role of traditional cultural values. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 41, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, T.J.; Conger, R.D.; Conger, K.J.; Martin, M.J.; Brody, G.; Simons, R.; Cutrona, C. Neighborhood disorder and children’s antisocial behavior: The protective effect of family support among Mexican American and African American families. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2012, 50, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leidy, M.S.; Guerra, N.G.; Toro, R.I. Positive parenting, family cohesion, and child social competence among immigrant Latino families. J. Fam. Psychol. 2010, 24, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, R. Culture-fair behavioral symptom differential assessment and intervention in dementing illness. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 1994, 8 (Suppl. 3), 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, M. Influence of Religious Coping on the Substance Use and HIV Risk Behaviors of Recent Latino Immigrants. Ph.D. Thesis, Florida International University, Miami, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veliz, E. Rising souls: Religion and family relationships among Latino adolescents. In Soul of Society: A Focus on the Lives of Children Youth; Warehime, M.N., Ed.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bentley, UK, 2014; pp. 151–172. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano, R.F.; Hawkins, J.D. The social development model: A theory of antisocial behavior. In Delinquency and Crime: Current Theories; Hawkings, J.D., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; pp. 149–196. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, B.R.; De Li, S.; Larson, D.B.; McCullough, M. A systematic review of the religiosity and delinquency literature A research note. J. Contemp. Crim. Justice 2000, 16, 32–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landor, A.; Simons, L.G.; Simons, R.L.; Brody, G.H.; Gibbons, F.X. The role of religiosity in the relationship between parents, peers, and adolescent risky sexual behavior. J. Youth Adolesc. 2011, 40, 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, D.A.; Lewin, A. Family religiosity, parental monitoring, and emerging adults’ sexual behavior. Religions 2019, 10, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaccard, J.; Blanton, H.; Dodge, T. Peer influences on risk behavior: An analysis of the effect of a close friend. Dev. Psychol. 2005, 41, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinsman, S.B.; Romer, D.; Furstenberg, F.F.; Schwarz, D.F. Early sexual initiation: The role of peer norms. Pediatrics 1998, 102, 1185–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandhorst, S.R.; Ferguson, B.; Sebby, R.A.; Weeks, R. The influence of peer sexual activity upon college students’ sexual behavior. N. Am. J. Psychol. 2012, 14, 111–122. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion, T.J.; McMahon, R.J. Parental monitoring and the prevention of child and adolescent problem behavior: A conceptual and empirical formulation. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 1998, 1, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, K.A. Friends: The role of peer influence across adolescent risk behaviors. J. Youth Adolesc. 2002, 31, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gaston, J.; Weed, S.; Jensen, L. Understanding gender differences in adolescent sexuality. Adolescence 1996, 31, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Driscoll, A.K.; Biggs, M.A.; Brindis, C.D.; Yankah, E. Adolescent Latino reproductive health: A review of the literature. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2001, 23, 255–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denner, J.; Coyle, K. Condom use among sexually active Latina girls in alternative high schools. In Urban Girls Revisited: Building Strengths; Leadbeater, B.J.R., Way, N., Eds.; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 281–300. [Google Scholar]

- Marín, B.V. HIV prevention in the Hispanic community: Sex, culture, and empowerment. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2003, 14, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, J.B.; Ritt-Olson, A.; Wagner, K.; Soto, D.; Baezconde-Garbanati, L. A comparison of acculturation measures among Hispanic/Latino adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 2007, 36, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phinney, J.S. Ethnic identity and acculturation. In Acculturation: Advances in Theory, Measurement, and Applied Research; Chun, K.M., Organista, P.B., Marín, G., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; pp. 63–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ryder, A.G.; Alden, L.E.; Paulhus, D.L. Is acculturation unidimensional or bidimensional? A head-to-head comparison in the prediction of personality, self-identity, and adjustment. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 79, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benet-Martínez, V.; Haritatos, J. Bicultural identity integration (BII): Components and psychosocial antecedents. J. Personal. 2005, 73, 1015–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]