Abstract

The objectives of the present manuscript were to review the literature on stigma toward survivors of intimate partner violence (IPV) and to identify the most widely used assessment techniques to investigate this issue. The PRISMA guidelines were followed, and the systematic review was registered in PROSPERO, registration number: CRD42022327410. PsycINFO, Scopus, Web of Science, and PubMed were searched. Two authors selected and extracted data from eligible studies. In total, 4220 hits were returned from the database search, and of them, 24 articles met the inclusion criteria. The articles included in the review confirm the presence of stigma toward IPV survivors, which can be divided into public stigma and self-stigma. Specifically, 17 studies were related only to public stigma, 1 study focused only on self-stigma, and 6 articles investigated aspects related to both public and self-stigma. Both qualitative and quantitative studies have been conducted on this topic. The considerations on the methodologies and assessment measures used in the included studies will be discussed in the results section. Based on the research included, it was possible to develop a contribution to the definition of stigma, which will be discussed in the article.

1. Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) corresponds to any behavior and conduct a person exerts against the partner that inflicts physical, psychological, or sexual harm [1]. Globally, around 30% of women are physically or sexually abused by a partner [2,3]. Considering IPV’s global diffusion, cultural factors must be taken into account when addressing this phenomenon. In fact, culture can play a key role in increasing or decreasing the risk of IPV and its associated outcomes, for example, by legitimizing violence in intimate relationships and by attributing a passive role to women [4,5,6].

Experiencing IPV contributes to the development of PTSD, depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and suicide attempts [7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. In addition, IPV survivors can experience another kind of victimization: Stigma [14]. Stigma is “a multileveled term alternately representing the cues or marks that signal stereotypes and prejudice, and the rubric representing the overall stereotypical and prejudicial process” [15] (p. 51). Consequently, it can be considered an umbrella term that includes stereotypes, prejudices, and discriminatory behaviors against a group of individuals [16,17,18]. Stereotypes have been defined as negative beliefs about a group of people [19], while the term prejudice refers to the emotional response that results from the acceptance of a stereotype [15,19,20]. Lastly, the behavioral implication of prejudice corresponds to discrimination [15,19,20]. Most research in the field has focused on stigma toward mental health, e.g., [21,22]. However, stigma affects different social groups, including IPV survivors [14,23,24].

Previous research has distinguished between public and self-stigma [15,19,20]. On the one hand, public stigma “comprises reactions of the general public towards a group based on stigma about that group” [25] (p. 530). Public stigma leads to the experience of everyday discrimination, ostracism, and professional inaction [26]. Regarding IPV survivors, they can experience victim-blaming attitudes—when the survivor is blamed for the violence she has been subjected to [27]—and secondary victimization—which corresponds to victim-blaming conducts and attitudes acted out by community service providers that cause additional trauma for survivors [28]. Consequently, public stigma can affect the help-seeking process of IPV survivors [14]. In addition to this, same-sex couples may face a wide range of specific prejudices, stereotypes, and negative feelings toward homosexuality—homophobia [29,30,31,32].

On the other hand, self-stigma is described as “the reactions of individuals who belong to a stigmatized group and turn the stigmatizing attitudes against themselves” [25] (p. 531). Experiencing this type of stigma results in feelings of shame and blame [25,33,34]. These feelings can affect the help-seeking process [25] and people’s self-esteem and self-efficacy [25,35].

The present systematic review aims to investigate stigma toward female IPV survivors based on the conceptualization of stigma mentioned above. Specifically, the research questions are the following: What is the state-of-the-art stigma against IPV survivors and its effects on them? What are the most widely used measures and assessment techniques implemented in the literature to address this issue?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

This review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA statement) guidelines [36]. The PRISMA checklists [37] for this review are provided in the Supplementary Material. The systematic review is registered in the PROSPERO database of systematic reviews (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/ (accessed on 15 February 2023); registration number: CRD42022327410. The search strategy has been conducted in the following electronic databases: Web of Science (WOS), Scopus, PubMed, and PsycINFO. The keywords included are the following: (intimate partner violen* OR domestic violen* OR domestic abus* OR Spous* abus* OR spous* violen*) AND (stigm* OR public stigm* OR self-stigm* OR discrimin* OR prejud* OR victim blam* OR second* victim* OR blam* OR stereotyp*).

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Manuscripts were included when they: (a) Were published in a peer-reviewed journal between January 2011 and December 2021, (b) were written in English or Italian, (c) concerned research conducted in an English or Italian speaking western country, (d) concerned the phenomenon of stigma toward female victims of intimate partner violence by a male partner in adulthood (>18 years old) both from a general population perspective and a survivor perspective.

Manuscripts were excluded when: (a) They were unpublished manuscripts and thesis, reviews, commentaries, editorials, conference proceedings, conference paper, meeting abstract, book chapter or opinion pieces, case reports, randomized controlled trial, (b) they did not include participants (i.e., general population, victims of violence) therefore, manuscripts concerning analysis of newspapers, posts/comments, etc., on social media, of archival data, of trial transcripts were excluded, (c) they were written in languages other than English and Italian, (d) articles that did not explicitly investigate the stigma or one of the following aspects of this phenomenon—which are stigm*, public stigm*, self-stigm*, discrimin*, prejud*, victim blam*, second* victim*, stereotyp*—in the objectives/hypotheses of the research have been excluded, (e) articles in which the constructs and the investigated phenomenon were not defined, (f) articles that did not focus only on intimate partner violence, but also investigated other typologies of violence.

2.3. Data Extraction

Study selection was a two-stage process: First, studies were selected on the basis of their titles and abstracts. Then, the two authors independently evaluated the full text of the potentially eligible studies. A standardized Excel form was used to extract data from eligible studies to assess their quality and evidence synthesis. This form includes authors, year of publication, aim/hypothesis, any secondary aims, type of stigma investigated, study design, measures, sample size, study population characteristics, comparison group (if present), sample size, methodology, measures, methodology and statistical analyses, results, conclusions, limitations of the study, limitations of the methodology, study risk of bias, strengths of the study, strengths of the measures, key words used, electronic database, date, notes, study included after screening, reason for exclusion during screening. Any disagreement between the reviewers was resolved by consensus.

2.4. Identified Studies

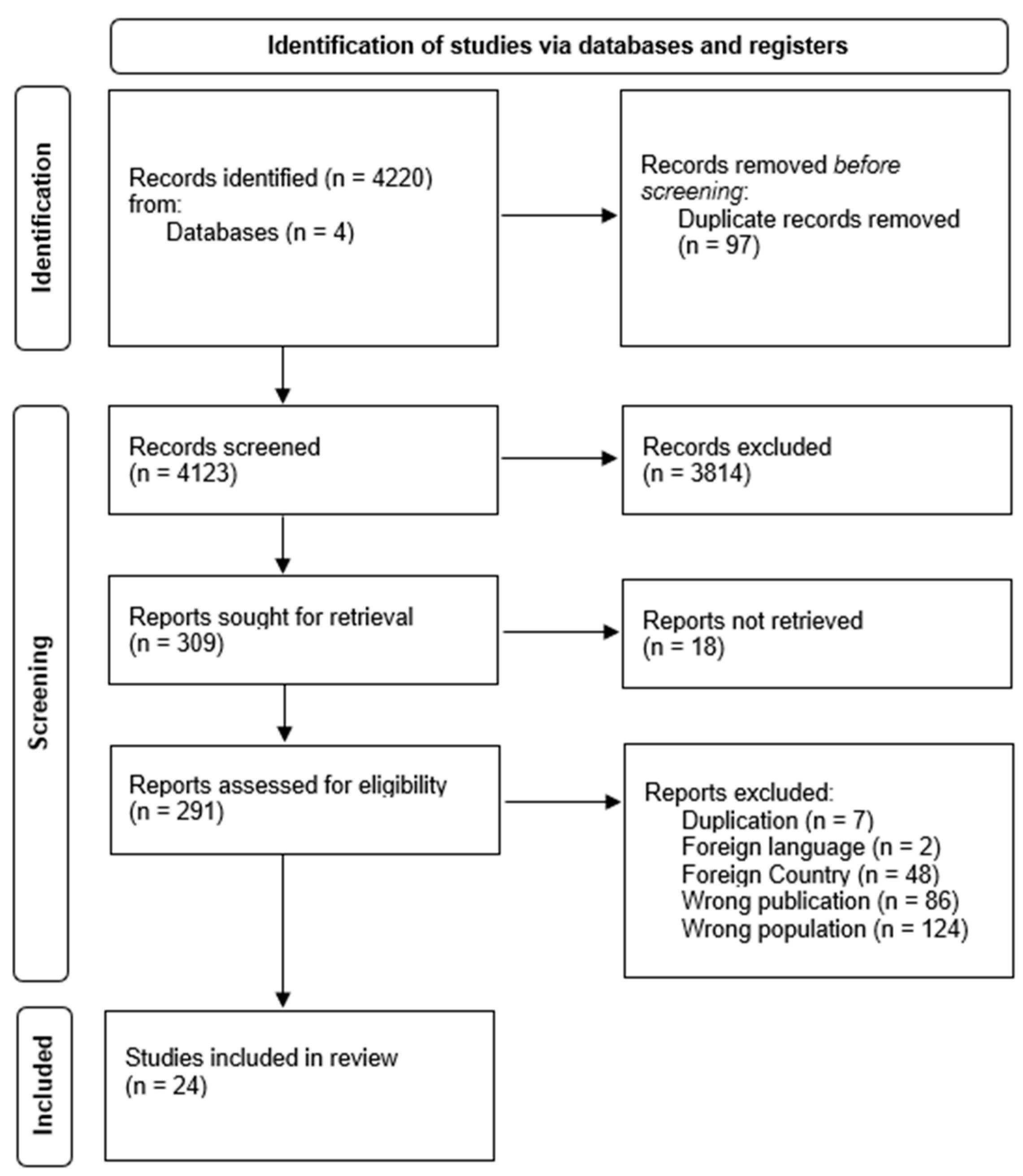

In total, 4220 hits were returned from the database search (see Figure 1). Then, all duplicates were removed (n = 97), which resulted in a sample of 4123 publications. The titles and abstracts of these publications were independently screened by two reviewers, FT and SM, and resulted in a sample of 309 articles ready for full text screening. However, 18 articles were not retrieved since it was not possible to access their full report. Consequently, the resulting number of articles assessed for eligibility was 291. However, 267 of them were excluded because they were duplicates or did not meet the inclusion criteria. The resulting sample of included articles is 24, that all met the quality assessment criteria (see Figure 1 and Table 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram.

Table 1.

Study characteristics.

3. Results

3.1. Defining Stigma toward IPV Survivors

This systematic review confirms that IPV survivors experience stigma in their daily lives. However, the 24 articles included in this review (see Table 1) show that a shared definition of stigma toward IPV survivors is missing.

By summarizing all the results of the studies included in the present review and applying previous theories on stigma referred to mental illness [15,19,20,66], it is possible to assume that even with this population, the definition of stigma as a phenomenon that includes marks and stereotypes that lead stigmatized individuals to experience prejudice and discrimination against them appears to be confirmed [15,16,19,20,66].

IPV survivors seem to be stigmatized when they do not have the following characteristics of ‘ideal victims’: (1) Weak, (2) they were doing something respectable when the violent episode occurred, (3) they cannot be held responsible for the circumstances in which the violence took place, (4) they faced bigger offenders, (5) they faced unknown perpetrators [56,67].

Furthermore, stereotypes about IPV survivors appear to correspond to domestic violence/IPV myths, which are “misconceptions and false beliefs about intimate partner violence, victims, and abusers” [33] (p. 330). The most common among these are the following: The survivor is held responsible for the abuse, the violence that occurs is trivialized, the perpetrator is somehow justified, the IPV is assumed exclusively to be in the form of physical abuse [33,42,46,65].

Prejudices against IPV survivors appear to be related to feelings of blame, shame, and fear. In fact, the general population seems to blame IPV survivors for the violence they experienced. IPV survivors can internalize this blame and begin to consider themselves responsible for the abuse received while simultaneously being ashamed of it [27,28,33,53]. For example, Meyer [53] showed that 64.3% of their sample of IPV survivors reported previous experiences with victim blame attitudes and the need to demonstrate to both formal and informal supporters that they were not responsible for their own victimization. In addition, these women feared blame and discriminatory behaviors [52,68].

Discrimination against IPV survivors appears to correspond to secondary victimization that women can experience in their interpersonal interactions [49]. Secondary victimization corresponds to “the victim-blaming attitudes, behaviors, and practices engaged in by community service providers, which result in the additional trauma for rape survivors” [69] (p. 56). An example of this is the difficulty faced by survivors when trying to speak in the courtroom [28,49,69]. Rivera and colleagues [28] showed that 63% of the participants reported previous experiences of secondary victimization characterized by feelings of blame, of being disbelieved or dismissed, and consequently, 67% of these women did not want to return to court because they did not feel safe, believed, and respected.

3.2. Public Stigma

Twenty-three studies investigated public stigma in IPV survivors (see Table 1). Most of these studies have shown the presence of stigmatizing attitudes toward IPV survivors, which contributed to the development of mental health problems, such as depression and PTSD symptoms [14,39,48,64]. In this sense, examples of negative public reactions are victim blame, shame, and discrediting attitudes [14].

Yamawaki and colleagues [65] showed the presence of victim-blaming attitudes in undergraduate students, and these results have been confirmed in other studies [33,42]. In contrast, Eigenberg and Policastro [27] showed that most of their participants were unwilling to blame survivors of abuse.

Stigmatizing attitudes appeared in formal and informal supporters as well: Gutowski and Goodman [49] showed that most of the women in their study reported experiencing harsh behaviors and judgments from court professionals. In this regard, Nikolova and colleagues [56] confirmed these results with respect to advocates. Despite this, hand therapists have shown low levels of victim-blaming attitudes [60]. This result is encouraging, considering the high possibility that survivors of physical or sexual abuse attend hand therapy clinics [60].

A factor that appears to play a key role in public stigma is gender: Men endorsed victim-blaming attitudes more often, compared to women [26,27,33,38,42,45,58,65]. Furthermore, Yamawaki and colleagues [65] have shown that male undergraduate students tended to trivialize IPV episodes more often than females.

Another factor that appears to affect public stigma is the type of relationship the woman has with the offender. Yamawaki and colleagues [65] showed that participants tended to blame the survivor more when she was dating the abuser compared to when she was married to him. Furthermore, the decision to stay or return to the abusive partner led to increased levels of victim blame [50,58,65].

Another factor that seems to play a key role in public stigma is the adhesion to sexist, patriarchal, or conservative values [26,51,58,65]. For example, Riley and Yamawaki [58] showed that people with higher values of benevolent sexism (BS) reported that they would not have provided any support to women who do not leave the abuser.

In conclusion, few studies showed no public stigma toward female IPV survivors [39,48,60]. For example, Dardis and colleagues [39] reported that women who revealed their IPV experience received more positive than negative social reactions.

3.3. Self-Stigma

Six studies showed the presence of self-stigma in IPV survivors (see Table 1). With regard to this, self-stigma seems to have connotations of guilt and shame. Flicker and colleagues [48] showed the presence of a self-blame coping strategy along with denial and disengagement in women seeking a protection order against an abusive partner. Furthermore, self-stigma appeared to contribute to the development of depressive and post-traumatic symptoms [48,54,63]. Additionally, the experience of judgmental responses from figures who should be supportive instead (e.g., lawyers, police officers, etc.) negatively affected the psychological well-being of survivors: Srinivas and DePrince [63] showed that unmet police expectations significantly predicted the severity of PTSD symptoms. Furthermore, IPV survivors who experienced stigmatizing attitudes from courtroom professionals reported feeling ashamed, worthless, or powerless [49]. In contrast, the supportive social network acted as a protective factor against the development of psychological disorders [48,63].

Furthermore, interiorizing public blame for their experience of violence and a related feeling of shame can hinder the help-seeking process [68] and the choice to interrupt the relationship with the perpetrator [68]. Furthermore, the internalization of patriarchal gender roles could also play a role in this matter [52]: Women who have internalized gender stereotypes can struggle to act against them and break their abusive relationships [51].

3.4. Researching Stigma toward Survivors of IPV

Both qualitative and quantitative studies have investigated stigma toward IPV survivors.

The qualitative studies included in the present review implemented semi-structured [28,53,54,63,64] and in-depth interviews [51]. Some of the methodologies and approaches used for the interviews were: The phenomenological approach [51], the life history approach [54], the analytic method [49]. Two studies have also included a focus group [51,54]. Qualitative research allows one to investigate the first-person experience, which results in a deep understanding of human behavior [70]. In this field, to the best of our knowledge, only interviews and focus groups have been conducted.

Concerning the quantitative studies included in the present review, four of them used the vignette methodology to investigate public perceptions of IPV survivors [38,50,52,65]. Furthermore, the following self-reports were used in the research included in the present review: The Social Reactions Questionnaire (SRQ; Ullman [40]), which focused on social responses to the disclosure of survivors of violence. Survivors had to report how often they received 48 different reactions from other people to their disclosure. The instrument had good validity and reliability [40].

The Domestic Violence Myth Acceptance Scale [DVMAS; Peters [45]], which is an 18-item questionnaire that measures the endorsement of domestic violence myths by participants. The reliability of the questionnaire is excellent and presents good validity in terms of face and content. However, divergent validity was only partially supported in the study by Peters [46].

The Supportive Attitudes Toward Victim Scale (SAVS) is a 15-item questionnaire developed by Riley and Yamawaki [58] to assess the degree to which a person has supportive attitudes toward a survivor of violence. A principal component analysis reported the presence of four subscales: Insisting Victim to Leave subscale (α = 0.76), Imposing Judgment subscale (α = 0.75), Traditional Value for Intimate Relationships subscale (α = 0.69), and Work Out Relationship (α = 0.60).

The Domestic Violence Blame Scale (DVBS) [55] is a 23-item scale that aims to assess the amount of blame an individual attributes to survivors of domestic violence. According to Bryant and Spencer [55], it presents adequate reliability and validity.

The Victim Blame Attribution Scale (VBA) [59] investigates victim-blame attitudes. VBA has five items, and Cronbach’s alpha was 0.73 for an American population.

The Perceived Seriousness of Violence measure is a 5-item questionnaire aimed at assessing the degree to which individuals perceive the severity of IPV episodes [59]. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.84.

The Excuse Perpetrator Measure [56] is a 4-item questionnaire that evaluates the excusing of the batterer of the respondents. The Cronbach alpha was 0.58.

The Physician Readiness to Manage Intimate Partner Violence Survey (PREMIS) is a questionnaire designed to assess the self-perceived readiness of physicians [71] or students [61] to handle patients with a history of violence. The questionnaire is reliable and valid, and it allows one to discriminate between trained from non-trained physicians.

A questionnaire was designed to evaluate the attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors of health care providers about IPV recognition and handling [61]. The questionnaire consists of 39 items with good internal reliability (α = 0.88).

The Attitudes Toward Crime Victims index assesses law personnel’s beliefs about survivors of violent crimes’ attitudes and behaviors [45,47]. The questionnaire showed high internal reliability (α = 0.822).

To the authors’ knowledge, four other questionnaires have been developed to investigate aspects of public stigma toward IPV survivors. Articles related to the validation of these questionnaires did not meet the inclusion criteria of the present review, however, they may be useful to those conducting research in this field. The questionnaires are the following: Victim-Blaming—Intimate Partner Violence Against Women Scale [72], Acceptability of Intimate Partner Violence Against Women-8 Scale [73], Willingness to Intervene in Cases of Intimate Partner Violence Scale [74]. Moreover, another questionnaire has been developed to investigate self-stigma: The intimate partner violence stigma scale [75].

4. Discussion

The current study aimed to assess stigma toward female IPV survivors using a systematic review. Twenty-four studies were included in the review and confirmed the feasibility of the definition of stigma as a phenomenon that includes stereotypes that lead the stigmatized group to experience prejudice and discrimination [15,16,19,20,66]. In the case of IPV, stereotypes appear to refer to myths of domestic violence/IPV that are shared by the general population and consist of blaming survivors, minimizing violence, justifying the perpetrator, and considering IPV as corresponding only to physical abuse [28,33,42,46]. Additionally, prejudices appear to correspond to feelings of blame, shame, and fear in IPV survivors, perpetrators, and the general population. In fact, the general population seems to blame IPV survivors for the violence they experienced, and survivors can internalize this blame—self-stigma [27,28,33,53]. Lastly, the discrimination faced by survivors of violence in the course of their interpersonal interactions appears to correspond to secondary victimization [28,49].

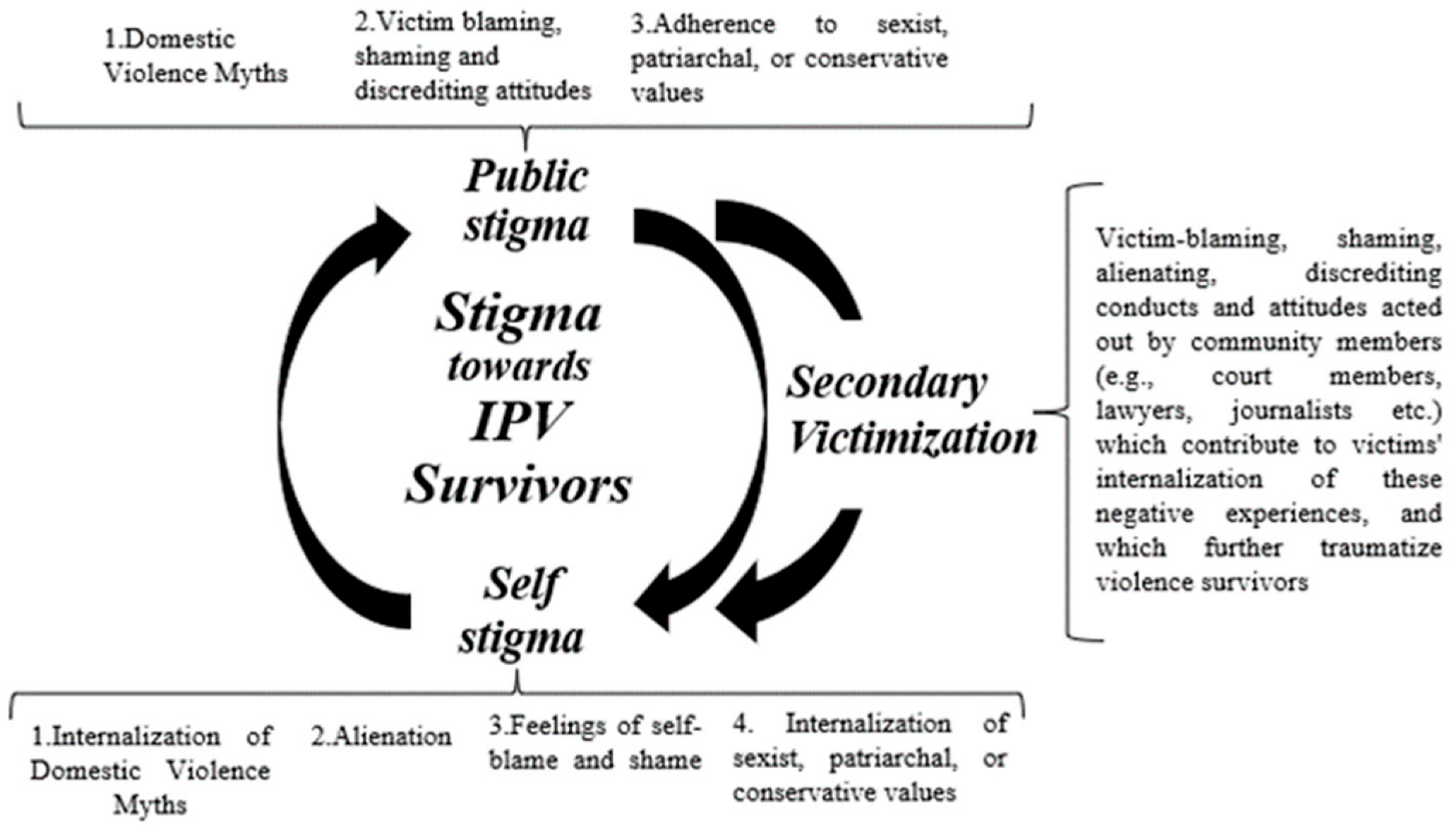

The results show that women experience both public and self-stigma and that the two are intertwined for this population. Specifically, the experience of public stigmatizing attitudes contributes to the internalization of these negative experiences—self-stigma—which can also reinforce public stigma, resulting in a vicious circle that can be difficult to break (see Figure 2). In this cycle, secondary victimization also seems to play an important role. In fact, secondary victimization seems to contribute to the development of self-stigma in IPV survivors, as it constitutes a further form of public victimization and traumatization. It seems that through the discriminatory conducts typical of secondary victimization, a survivor could internalize the public stigma suffered and start adhering to such stigmatizing attitudes, and self-stigma.

Figure 2.

Definition of stigma towards IPV survivors.

Both public and self-stigma appear to have negative implications for the psychological well-being of survivors. IPV survivors reported depression and post-traumatic symptoms related to the stigma suffered [39,41,48,64]. Furthermore, stigma appears to affect the survivors’ help-seeking process and the support offered by formal and informal supporters as well. In fact, only a few studies showed that participants experienced more positive than negative social reactions to their disclosure [39,48,60].

Research in this field has been carried out through qualitative and quantitative studies. In this regard, several previously mentioned self-reports can allow researchers to investigate important components of stigma toward IPV survivors, e.g., [55,59]. However, to our knowledge, a questionnaire that addresses all aspects of public stigma toward IPV survivors is lacking. In addition, only one questionnaire investigates self-stigma [75].

Implications for Practice, Intervention, and Policy

This systematic review presents important implications for intervention. Regarding self-stigma, women stressed their desire to overcome this barrier [53]. Consequently, psychological and social support for IPV survivors should focus on this issue [53]. Previous literature shows the benefits of targeting internalized stigma in the clinical setting [76,77,78]. In fact, psychological interventions focused specifically on this aspect appear to improve patients’ levels of empowerment, self-esteem, self-efficacy, and functioning in post hoc analyses [76,77,78,79]. Consequently, psychological and social support for IPV survivors should also focus on this issue [53].

Furthermore, anti-stigma prevention campaigns that aim to promote a non-stigmatizing culture must be developed to target public stigma [51]. In this regard, Keller and Honea [51] presented six tips that could be used when designing this kind of intervention: (1) Avoidance of stereotypical gender messages, (2) IPV should not be minimized, (3) survivors should not be blamed, (4) personal and social support for both batterers and survivors should be addressed, (5) access to IPV resources for the general population should be promoted, (6) a community-based approach should be used.

Additionally, formal supporters (such as police force, lawyers, etc.) should be trained on how to properly manage IPV cases. In this regard, Fleming and Franklin [45] showed that IPV training resulted in higher levels of preparedness and self-confidence in responding to family violence cases in members of the police force.

This review presents some limitations. First, the present review focused only on intimate partner violence. However, the literature also shows the presence of stigma against survivors of other types of violence (such as rape), e.g., [80,81]. Second, the present research aimed to investigate male-perpetrated violence against a female partner. However, the literature has shown the presence of partner abuse acted against male partners and in LGBT couples [82,83]. The stigmas these survivors face can take on different aspects that need to be explored in future studies. Third, the focus of the present review was on studies from 2011 onwards. This year was chosen due to its historical relevance for women’s rights with the Istanbul Convention [84], an international convention that defined a framework to protect women from all forms of violence. However, articles before that date are not included in this review. Fourth, the objective of the present review was to develop a comprehensive picture of the stigma against female IPV survivors in the western world. However, articles related to other countries were not included and therefore, should be addressed in future studies. Lastly, most studies investigated the phenomenon of public stigma. Consequently, more research on self-stigma should also be done to better understand this phenomenon. Furthermore, other qualitative methodological approaches, such as participatory action research, could be implemented in this regard, and psychological interventions targeted specifically at the self-stigma experienced by IPV survivors should be developed.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review stresses the relevance of the stigma phenomenon against IPV survivors, which affects their psychological well-being, their safety, and hinders their help-seeking process.

Therefore, it is important to develop psychological interventions with IPV survivors that aim to overcome the negative implications of stigma. Moreover, there seems to be a need for the development of anti-stigma campaigns aimed at promoting a non-stigmatizing culture.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/bs13030194/s1, PRISMA checklist; PRISMA_2020_abstract_checklist.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M. and F.T.; methodology, S.M. and F.T.; investigation, S.M. and F.T.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M. and F.T.; writing—review and editing, S.M. and F.T.; supervision, S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- WHO; PAHO. Understanding and Addressing Violence Against Women: Intimate Partner Violence; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Canto, J.M.; Vallejo-Martín, M.; Perles, F.; San Martín, J. The Influence of Ideological Variables in the Denial of Violence Against Women: The Role of Sexism and Social Dominance Orientation in the Spanish Context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Global and Regional Estimates of Violence Against Women. Prevalence and Health Effects of Intimate Partner Violence and Non-Partner Sexual Violence; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- White, M.E.; Satyen, L. Cross-cultural differences in intimate partner violence and depression: A systematic review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2015, 24, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, A.; Silverman, J. Violence Against Immigrant Women:The Roles of Culture, Context, and Legal Immigrant Status on Intimate Partner Violence. Violence Against Women 2002, 8, 367–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latta, R.; Goodman, L. Considering the Interplay of Cultural Context and Service Provision in Intimate Partner Violence: The Case of Haitian Immigrant Women. Violence Against Women 2005, 11, 1441–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracewell, K.; Jones, C.; Haines-Delmont, A.; Craig, E.; Duxbury, J.; Chantler, K. Beyond intimate partner relationships: Utilising domestic homicide reviews to prevent adult family domestic homicide. J. Gend. Based Violence 2022, 6, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, J.; Levell, J.; Cole, T. An intersectional analysis of domestic abuse perpetrator service adaptation during COVID-19: Findings from the UK, Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Romania. J. Gend. Based Violence 2022, 6, 348–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hester, M. Special issue on the COVID-19 pandemic and gender-based violence. J. Gend. Based Violence 2022, 6, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannarini, S.; Taccini, F.; Rossi, A.A. Women and violence: Alexithymia, relational competence and styles, and satisfaction with life: A comparative profile analysis. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taccini, F.; Rossi, A.A.; Mannarini, S. The Women’s EmotionS, Trauma, and EmpowErMent (W-ES.T.EEM) study protocol: A psycho-educational support intervention for victims of domestic violence—A randomized controlled trial. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e060672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taccini, F.; Rossi, A.A.; Mannarini, S. Intergenerational Transmission of Relational Styles: Current Considerations. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 672961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevillion, K.; Oram, S.; Feder, G.; Howard, L.M. Experiences of Domestic Violence and Mental Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e51740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overstreet, N.M.; Willie, T.C.; Sullivan, T.P. Stigmatizing Reactions Versus General Negative Reactions to Partner Violence Disclosure as Predictors of Avoidance Coping and Depression. J. Interpers. Violence 2019, 34, 1734–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P.W.; Larson, J.E.; Kuwabara, S.A. Social psychology of stigma for mental illness: Public stigma and self-stigma. In Social Psychological Foundations of Clinical Psychology; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mannarini, S.; Rossi, A.; Munari, C. How do education and experience with mental illness interact with causal beliefs, eligible treatments and stigmatising attitudes towards schizophrenia? A comparison between mental health professionals, psychology students, relatives and patients. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, S.; Jackson, V.W.; Chong, J.; Choe, K.; Tay, C.; Wong, J.; Yang, L.H. Systematic Review of Cultural Aspects of Stigma and Mental Illness among Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups in the United States: Implications for Interventions. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2021, 68, 486–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Driscoll, C.; Heary, C.; Hennessy, E.; McKeague, L. Explicit and implicit stigma towards peers with mental health problems in childhood and adolescence. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2012, 53, 1054–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P.W. Target-specific stigma change: A strategy for impacting mental illness stigma. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2004, 28, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P.W.; Shapiro, J.R. Measuring the impact of programs that challenge the public stigma of mental illness. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 907–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannarini, S.; Boffo, M.; Rossi, A.; Balottin, L. Etiological beliefs, treatments, stigmatizing attitudes toward schizophrenia. What do Italians and Israelis think? Front. Psychol. 2018, 8, 2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannarini, S.; Reikher, A.; Shani, S.; Shani-Zinovich, I. The role of secure attachment, empathic self-efficacy, and stress perception in causal beliefs related to mental illness—A cross-cultural study: Italy versus Israel. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2017, 10, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, C.; Davies, P.; Ewin, R. ‘He hits me and that’s just how it is here’: Responding to domestic abuse in rural communities. J. Gend. Based Violence 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavemann, B.; Helfferich, C.; Kindler, H.; Nagel, B. Sexual re-victimisation of adolescent girls in institutional care with a history of sexual violence in childhood: Empirical results and conclusions for prevention. J. Gend. Based Violence 2018, 2, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüsch, N.; Angermeyer, M.C.; Corrigan, P.W. Mental illness stigma: Concepts, consequences, and initiatives to reduce stigma. Eur. Psychiatry J. Assoc. Eur. Psychiatr. 2005, 20, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollero, C.; De Piccoli, N. Myths about Intimate Partner Violence and Moral Disengagement: An Analysis of Sociocultural Dimensions Sustaining Violence against Women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eigenberg, H.; Policastro, C. Blaming Victims in Cases of Interpersonal Violence: Attitudes Associated With Assigning Blame to Female Victims. Women Crim. Justice 2016, 26, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, E.A.; Sullivan, C.M.; Zeoli, A.M. Secondary Victimization of Abused Mothers by Family Court Mediators. Fem. Criminol. 2012, 7, 234–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eric, S.; Reyes, M.; Camille, M.; Alday, A.; Jay, J.; Aurellano, A.; Raven, R.; Escala, S.; Ermelo, V.; Hernandez, P.; et al. Minority Stressors and Attitudes Toward Intimate Partner Violence Among Lesbian and Gay Individuals. Sex. Cult. 2022, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedele, E.; Juster, R.P.; Guay, S. Stigma and Mental Health of Sexual Minority Women Former Victims of Intimate Partner Violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, Np22732–Np22758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, E.K.; Helfrich, C.A. Lesbian Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence. J. Gay Lesbian Soc. Serv. 2005, 18, 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J. How homophobic propaganda produces vernacular prejudice in authoritarian states. Sexualities 2023, 13634607221144624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Policastro, C.; Payne, B.K. The Blameworthy Victim: Domestic Violence Myths and the Criminalization of Victimhood. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 2013, 22, 329–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.C.L.; Chio, F.H.N.; Mak, W.W.S.; Corrigan, P.W.; Chan, K.K.Y. Internalization process of stigma of people with mental illness across cultures: A meta-analytic structural equation modeling approach. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 87, 102029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yechezkel, R.; Ayalon, L. Social Workers’ Attitudes towards Intimate Partner Abuse in Younger vs. Older Women. J. Fam. Violence 2013, 28, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bothamley, S.; Tully, R. Understanding revenge pornography: Public perceptions of revenge pornography and victim blaming. J. Aggress. Confl. Peace Res. 2017, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dardis, C.M.; Davin, K.R.; Lietzau, S.B.; Gidycz, C.A. Disclosing Unwanted Pursuit Victimization: Indirect Effects of Negative Reactions on PTSD Symptomatology Among Undergraduate Women. J. Interpers. Violence 2019, 36, 10431–10453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullman, S.E. Psychometric Characteristics of the Social Reactions Questionnaire: A Measure of Reactions to Sexual Assault Victims. Psychol. Women Q. 2000, 24, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePrince, A.P.; Welton-Mitchell, C.; Srinivas, T. Longitudinal Predictors of Women's Experiences of Social Reactions Following Intimate Partner Abuse. J. Interpers. Violence 2014, 29, 2509–2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, F.; Hutchinson, M. Student nurses’ knowledge and attitudes towards domestic violence: Results of survey highlight need for continued attention to undergraduate curriculum. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 26, 2286–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, P.; Fiske, S.T. The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 70, 491–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, C.; Di Napoli, I.; Esposito, C.; Carnevale, S.; Arcidiacono, C. Violence Against Women: A Not in My Back Yard (NIMBY) Phenomenon. Violence Gend. 2020, 7, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, J.C.; Franklin, C.A. Predicting Police Endorsement of Myths Surrounding Intimate Partner Violence. J. Fam. Violence 2021, 36, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, J. Measuring Myths about Domestic Violence: Development and Initial Validation of the Domestic Violence Myth Acceptance Scale. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2008, 16, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ask, K. A survey of police officers' and prosecutors’ beliefs about crime victim behaviors. J. Interpers. Violence 2010, 25, 1132–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flicker, S.M.; Cerulli, C.; Swogger, M.T.; Talbot, N.L. Depressive and posttraumatic symptoms among women seeking protection orders against intimate partners: Relations to coping strategies and perceived responses to abuse disclosure. Violence Against Women 2012, 18, 420–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutowski, E.; Goodman, L. “Like I’m Invisible”: IPV Survivor-Mothers’ Perceptions of Seeking Child Custody through the Family Court System. J. Fam. Violence 2020, 35, 441–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halket, M.; Gormley, K.; Mello, N.; Rosenthal, L.; Mirkin, M. Stay With or Leave the Abuser? The Effects of Domestic Violence Victim’s Decision on Attributions Made by Young Adults. J. Fam. Violence 2014, 29, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, S.N.; Honea, J.C. Navigating the gender minefield: An IPV prevention campaign sheds light on the gender gap. Glob. Public Health 2016, 11, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Hogge, I. Intimate Partner Violence among Asian Indian Women in the United States: Recognition of Abuse and Help-Seeking Attitudes. Int. J. Ment. Health 2015, 44, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S. Still blaming the victim of intimate partner violence? Women’s narratives of victim desistance and redemption when seeking support. Theor. Criminol. 2015, 20, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinley, C.E.; Lilly, J.M.; Knipp, H.; Liddell, J.L. “A Dad Can Get the Money and the Mom Stays at Home”: Patriarchal Gender Role Attitudes, Intimate Partner Violence, Historical Oppression, and Resilience Among Indigenous Peoples. Sex Roles 2021, 85, 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, S.A.; Spencer, G.A. University Students’ Attitudes About Attributing Blame in Domestic Violence. J. Fam. Violence 2003, 18, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolova, K.; Steiner, J.J.; Postmus, J.L.; Hetling, A.; Johnson, L. Administering the U.S. Family Violence Option: The role of stigma in waiver recommendations. Health Soc. Care Community 2021, 29, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, J.; Johnson, L.; Hetling, A.; Lin, H.-F.; Postmus, J. Creating a Tool for Assessing Domestic Violence Risk and Impact Among TANF Clients. Adv. Soc. Work 2019, 19, 157–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, C.E.; Yamawaki, N. Who Is Helpful? Examining the Relationship Between Ambivalent Sexism, Right-Wing Authoritarianism, and Intentions to Help Domestic Violence Victims. SAGE Open 2018, 8, 2158244018781899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamawaki, N.; Ostenson, J.; Brown, C.R. The Functions of Gender Role Traditionality, Ambivalent Sexism, Injury, and Frequency of Assault on Domestic Violence Perception: A Study Between Japanese and American College Students. Violence Against Women 2009, 15, 1126–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivagurunathan, M.; Packham, T.; Dimopoulos, L.; Murray, R.; Madden, K.; MacDermid, J.C. Hand therapists’ attitudes, environmental supports, and self-efficacy regarding intimate partner violence in their practice. J. Hand Ther. Off. J. Am. Soc. Hand Ther. 2019, 32, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiuro, R.D.; Vitaliano, P.P.; Sugg, N.K.; Thompson, D.C.; Rivara, F.P.; Thompson, R.S. Development of a health care provider survey for domestic violence: Psychometric properties. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2000, 19, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, P.D.; Nouer, S.S.; Mackey, S.T.; Tipton, N.G.; Lloyd, A.K. Psychometric properties of an intimate partner violence tool for health care students. J. Interpers. Violence 2011, 26, 1012–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, T.; DePrince, A.P. Links between the police response and women’s psychological outcomes following intimate partner violence. Violence Vict. 2015, 30, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woerner, J.; Wyatt, J.; Sullivan, T.P. If You Can't Say Something Nice: A Latent Profile Analysis of Social Reactions to Intimate Partner Violence Disclosure and Associations With Mental Health Symptoms. Violence Against Women 2019, 25, 1243–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamawaki, N.; Ochoa-Shipp, M.; Pulsipher, C.; Harlos, A.; Swindler, S. Perceptions of domestic violence: The effects of domestic violence myths, victim's relationship with her abuser, and the decision to return to her abuser. J. Interpers. Violence 2012, 27, 3195–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrigan, P. How stigma interferes with mental health care. Am. Psychol. 2004, 59, 614–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christie, N. The ideal victim. In From Crime Policy to Victim Policy; Fattah, E., Ed.; MacMillan: Basingstoke, UK, 1986; pp. 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Scheffer Lindgren, M.; Renck, B. ‘It is still so deep-seated, the fear’: Psychological stress reactions as consequences of intimate partner violence. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2008, 15, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, R. What really happened? A validation study of rape survivors’ help-seeking experiences with the legal and medical systems. Violence Vict. 2005, 20, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chandler, R.; Anstey, E.; Ross, H. Listening to Voices and Visualizing Data in Qualitative Research: Hypermodal Dissemination Possibilities. SAGE Open 2015, 5, 2158244015592166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, L.M.; Alpert, E.; Harris, J.M., Jr.; Surprenant, Z.J. A tool for measuring physician readiness to manage intimate partner violence. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2006, 30, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Fernandez, M.; Gracia, E.; Lila, M. Assessing Victim-Blaming Attitudes in Cases of Intimate Partner Violence against Women: Development and Validation of the VB-IPVAW Scale. Psychosoc. Interv. 2018, 27, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Fernández, M.; Gracia, E.; Lila, M. A Short Measure of Acceptability of Intimate Partner Violence Against Women: Development and Validation of the A-IPVAW-8 Scale. Assessment 2022, 29, 896–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gracia, E.; Martín-Fernández, M.; Marco, M.; Santirso, F.A.; Vargas, V.; Lila, M. The Willingness to Intervene in Cases of Intimate Partner Violence Against Women (WI-IPVAW) Scale: Development and Validation of the Long and Short Versions. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, A.; Overstreet, N.M.; Murray, C.E. The Intimate Partner Violence Stigma Scale: Initial Development and Validation. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, 7456–7479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T.-Y.; Chang, S.-C.; Chu, H.; Yang, C.-Y.; Ou, K.-L.; Chung, M.-H.; Chou, K.-R. The effects of assertiveness training in patients with schizophrenia: A randomized, single-blind, controlled study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2013, 69, 2549–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Li, Y.; Yang, B.X.; Chen, J.; Zhao, P. Psychological interventions for personal stigma of patients with schizophrenia: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 148, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, L.; Byrne, R.; Varese, F.; Morrison, A.P. Psychosocial interventions for internalised stigma in people with a schizophrenia-spectrum diagnosis: A systematic narrative synthesis and meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 2016, 176, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shih, C.-A.; Huang, J.-H.; Yang, M.-H. Anti-stigma psychosocial intervention effects on reducing mental illness self-stigma and increasing self-esteem among patients with schizophrenia in Taiwan: A quasi-experiment. Asian J. Psychiatry 2022, 73, 103171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welfare-Wilson, A.; J, B. “Were you wearing underwear?” Stigma and fears around sexual violence: A narrative of stranger rape and considerations for mental health nurses when working with survivors. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.; Canales, E.; Amacker, A.; Backstrom, T.; Gidycz, C. Stigma-Threat Motivated Nondisclosure of Sexual Assault and Sexual Revictimization A Prospective Analysis. Psychol. Women Q. 2011, 35, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ard, K.L.; Makadon, H.J. Addressing Intimate Partner Violence in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Patients. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2011, 26, 930–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskey, P.; Bates, E.A.; Taylor, J.C. A systematic literature review of intimate partner violence victimisation: An inclusive review across gender and sexuality. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2019, 47, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence [Istanbul Convention]. 2011. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/istanbul-convention/home? (accessed on 15 February 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).