Who Is Afraid of Monkeypox? Analysis of Psychosocial Factors Associated with the First Reactions of Fear of Monkeypox in the Italian Population

Abstract

1. Introduction

Aims

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedures

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Ad Hoc Quality of Life COVID-19-Related Measure Used for the Study with Factor Loadings

| ITEMS | Current Perceived QoL | Worsening QoL Attributed to the COVID-19 Pandemic |

| 1. How do you evaluate your current physical health? | 0.569 | 0.010 |

| 2. How do you evaluate your current state of psychological well-being? | 0.676 | −0.164 |

| 3. How do you evaluate your current social life? | 0.759 | −0.127 |

| 4. How do you evaluate your current emotional life? | 0.835 | −0.113 |

| 5. How do you evaluate your current sex life? | 0.770 | −0.121 |

| 6. How much do you think the COVID-19 pandemic and its social effects (such as lockdowns and other restrictions) have NEGATIVELY INFLUENCED your current physical health? | −0.022 | 0.691 |

| 7. How much do you think the COVID-19 pandemic and its social effects (such as lockdowns and other restrictions) have NEGATIVELY INFLUENCED your current state of psychological well-being? | 0.022 | 0.765 |

| 8. How much do you think the COVID-19 pandemic and its social effects (such as lockdowns and other restrictions) have NEGATIVELY INFLUENCED your current social life? | −0.087 | 0.815 |

| 9. How much do you think the COVID-19 pandemic and its social effects (such as lockdowns and other restrictions) have NEGATIVELY INFLUENCED your current emotional life? | −0.253 | 0.805 |

| 10. How much do you think the COVID-19 pandemic and its social effects (such as lockdowns and other restrictions) have NEGATIVELY INFLUENCED your current sex life? | −0.257 | 0.698 |

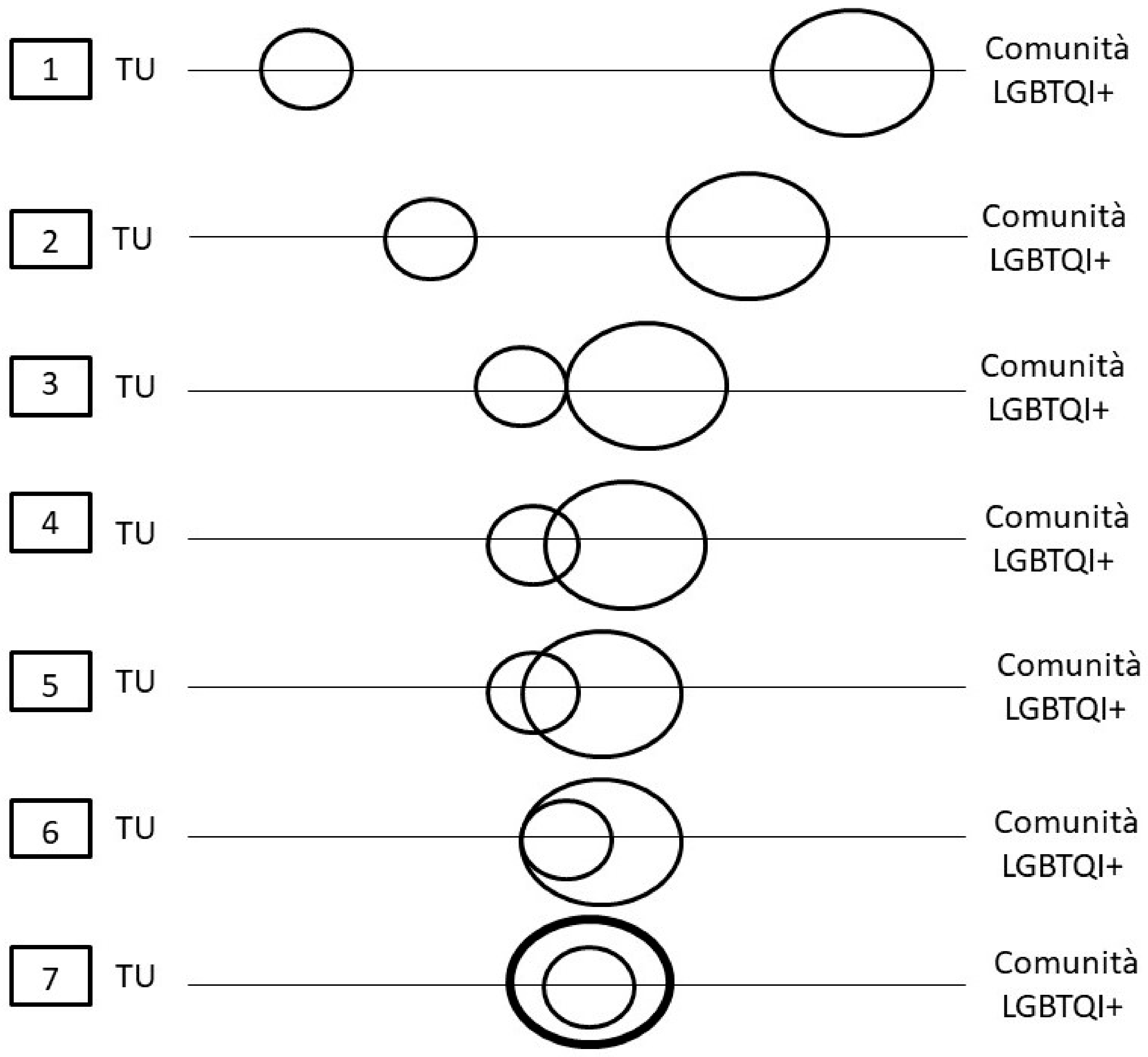

Appendix B. Visual Item on Different Distances between the Respondent and the LGBTQI+ Community Used to Evaluate the Perceived Closeness between the Person and the LGBTQI+ Community

References

- Von Magnus, P.; Andersen, E.K.; Petersen, K.B.; Birch-Andersen, A. A pox-like disease in cynomolgus monkeys. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Scand. 1959, 46, 156–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunge, E.M.; Hoet, B.; Chen, L.; Lienert, F.; Weidenthaler, H.; Baer, L.R.; Steffen, R. The changing epidemiology of human monkeypox—A potential threat? A systematic review. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ECDC-European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Navigating Monkeypox: Considerations for Gay and Bisexual Men and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men. Published the 10th of June 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/navigating-monkeypox-considerations-gay-and-bisexual-men-and-msm (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- ECDC-European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Rapid Risk Assessment. Monkeypox Multi-Country Outbreak. Published the 23rd of May 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/risk-assessment-monkeypox-multi-country-outbreak (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Bragazzi, N.L.; Kong, J.D.; Mahroum, N.; Tsigalou, C.; Khamisy-Farah, R.; Converti, M.; Wu, J. Epidemiological trends and clinical features of the ongoing monkeypox epidemic: A preliminary pooled data analysis and literature review. J. Med. Virol. 2022, 95, e27931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt-Sane, M.; Abbas, S.; Karam, S.; Palmer, J. RCCE Strategies for Monkeypox Response; Social Science in Humanitarian Action (SSHAP): London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO–World Health Organization. Multi-Country Monkeypox Outbreak: Situation Update (as of June 8). (n.d.). Retrieved 12 June 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2022-DON392 (accessed on 4 July 2022).

- Hedge, B.; Devan, K.; Catalan, J.; Cheshire, A.; Ridge, D. HIV-related stigma in the UK then and now: To what extent are we on track to eliminate stigma? A qualitative investigation. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starks, T.J.; Rendina, H.J.; Breslow, A.S.; Parsons, J.T.; Golub, S.A. The Psychological Cost of Anticipating HIV Stigma for HIV-Negative Gay and Bisexual Men. AIDS Behav. 2013, 17, 2732–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, C.T.; Canteras, N.S. The many paths to fear. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 13, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwin, C. The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. J. Anthr. Inst. Great Br. Irel. 1873, 2, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.; Walker, D.L.; Miles, L.; Grillon, C. Phasic vs Sustained Fear in Rats and Humans: Role of the Extended Amygdala in Fear vs Anxiety. Neuropsychopharmacology 2010, 35, 105–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobbs, D.; Yu, R.; Rowe, J.B.; Eich, H.; FeldmanHall, O.; Dalgleish, T. Neural activity associated with monitoring the oscillating threat value of a tarantula. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 20582–20586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adolphs, R. The biology of fear. Curr. Biol. 2013, 23, R79–R93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Sattar, U. Conceptualizing COVID-19 and Public Panic with the Moderating Role of Media Use and Uncertainty in China: An Empirical Framework. Healthcare 2020, 8, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerhold, L. COVID-19: Risk Perception and Coping Strategies; PsyArXiv: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, K.M.; Harris, C.; Drawve, G. Fear of COVID-19 and the mental health consequences in America. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2020, 12 (Suppl. S1), S17–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovanardi, G.; Bincoletto, A.F.; Baiocco, R.; Ferrari, M.; Gentile, D.; Siri, M.; Tanzilli, A.; Lingiardi, V. Lockdown dreams: Dream content and emotions during the COVID-19 pandemic in an italian sample. Psychoanal. Psychol. 2022, 39, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakpour, A.H.; Griffiths, M.D. The fear of COVID-19 and its role in preventive behaviors. J. Concurr. Disord. 2020, 2, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.; Gheshlagh, R.G.; Dalvand, S.; Saedmoucheshi, S.; Li, Q. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Fear of COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 661078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, C.M.; Suttiwan, P.; Arato, N.; Zsido, A.N. On the Nature of Fear and Anxiety Triggered by COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 581314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonagy, P.; Allison, E. The role of mentalizing and epistemic trust in the therapeutic relationship. Psychotherapy 2014, 51, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurist, E.L. Mentalized affectivity. Psychoanal. Psychol. 2005, 22, 426–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonagy, P. An attachment theory approach to treatment of the difficult patient. Bull. Menn. Clin. 1998, 62, 147. [Google Scholar]

- Nimbi, F.M.; Giovanardi, G.; Baiocco, R.; Tanzilli, A.; Lingiardi, V. Monkeypox: New epidemic or fake news? Study of psychological and social factors associated with fake news attitudes of monkeypox in Italy. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatti, A.; Riva, N. Anguish and fears about attitude towards COVID-19 vaccines: Contrasts between yes and no vax. Discov. Psychol. 2022, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.; Tanzer, M.; Saunders, R.; Booker, T.; Allison, E.; Li, E.; O’Dowda, C.; Luyten, P.; Fonagy, P. Development and validation of a self-report measure of epistemic trust. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liotti, M.; Milesi, A.; Spitoni, G.F.; Tanzilli, A.; Speranza, A.M.; Parolin, L.; Campbell, C.; Fonagy, P.; Lingiardi, V.; Giovanardi, G. Unpacking trust: The Italian validation of the Epistemic Trust, Mistrust, and Credulity Questionnaire (ETMCQ). PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0280328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roets, A.; Van Hiel, A. Item selection and validation of a brief, 15-item version of the Need for Closure Scale. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2011, 50, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, D.M.; Kruglanski, A.W. Individual differences in need for cognitive closure. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 67, 1049–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roets, A.; Van Hiel, A. Separating Ability from Need: Clarifying the Dimensional Structure of the Need for Closure Scale. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 33, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derogatis, L.R. Brief symptom inventory 18. In Mental Measurements Yearbook; Johns Hopkins University: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2001; Volume 15. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, D.M.; Rudenstine, S.; Alaluf, R.; Jurist, E.L. Development and validation of the Brief-Mentalized Affectivity Scale: Evidence from cross-sectional online data and an urban community-based mental health clinic. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 77, 2638–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liotti, M.; Spitoni, G.F.; Lingiardi, V.; Marchetti, A.; Speranza, A.M.; Valle, A.; Jurist, E.; Giovanardi, G. Mentalized affectivity in a nutshell: Validation of the Italian version of the Brief-Mentalized Affectivity Scale (B-MAS). PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herek, G.M. Heterosexuals’ attitudes toward bisexual men and women in the United States. J. Sex Res. 2002, 39, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimbi, F.M. Development and Validation of the Sex-Positive Attitudes Scale; Department of Dynamic and Clinical Psychology and Health Studies, Sapienza University of Rome: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, D.G.; Fick, C. Measuring Social Desirability: Short Forms of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1993, 53, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrocelli, J.V. Hierarchical Multiple Regression in Counseling Research: Common Problems and Possible Remedies. Meas. Evaluation Couns. Dev. 2003, 36, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M. Stepwise versus Hierarchical Regression: Pros and Cons. Online Submission. 2007. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED534385 (accessed on 4 July 2022).

- Italian Ministry of Health. Vaiolo delle Scimmie. Situazione in Italia–Bollettino del 1 Luglio 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/portale/malattieInfettive/dettaglioSchedeMalattieInfettive.jsp?archivio=20220701&cerca=&lingua=italiano&id=254&area=Malattie+infettive&menu=indiceAZ&tab=8 (accessed on 4 July 2022).

- Mileto, D.; Riva, A.; Cutrera, M.; Moschese, D.; Mancon, A.; Meroni, L.; Giacomelli, A.; Bestetti, G.; Rizzardini, G.; Gismondo, M.R.; et al. New challenges in human monkeypox outside Africa: A review and case report from Italy. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 49, 102386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nimbi, F.M.; Galizia, R.; Rossi, R.; Limoncin, E.; Ciocca, G.; Fontanesi, L.; Jannini, E.A.; Simonelli, C.; Tambelli, R. The Biopsychosocial Model and the Sex-Positive Approach: An Integrative Perspective for Sexology and General Health Care. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2021, 19, 894–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimbi, F.M.; Rosati, F.; Esposito, R.M.; Stuart, D.; Simonelli, C.; Tambelli, R. Chemsex in Italy: Experiences of Men Who Have Sex with Men Consuming Illicit Drugs to Enhance and Prolong Their Sexual Activity. J. Sex. Med. 2020, 17, 1875–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimbi, F.M.; Rosati, F.; Esposito, R.M.; Stuart, D.; Simonelli, C.; Tambelli, R. Sex in Chemsex: Sexual Response, Motivations, and Sober Sex in a Group of Italian Men Who Have Sex with Men With Sexualized Drug Use. J. Sex. Med. 2021, 18, 1955–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Morales, A.J.; Lopardo, G. Monkeypox: Another Sexually Transmitted Infection? Pathogens 2022, 11, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, G.P.W.; Ramsay, J.E. Salvation with fear and trembling? Scrupulous fears inconsistently mediate the relationship between religion and well-being. Ment. Heal. Relig. Cult. 2019, 22, 844–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Uddin, Z.; Banik, P.C.; Hegazy, F.A.; Zaman, S.; Ambia, A.S.M.; Bin Siddique, K.; Islam, R.; Khanam, F.; Bahalul, S.M.; et al. Knowledge, Attitude, Practice, and Fear of COVID-19: An Online-Based Cross-cultural Study. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisal, H.; Sutar, S.; Sastry, J.; Kapadia-Kundu, N.; Joshi, A.; Joshi, M.; Leslie, J.; Scotti, L.; Bharucha, K.; Suryavanshi, N.; et al. Nurses’ Health Education Program in India Increases HIV Knowledge and Reduces Fear. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 2007, 18, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Crosta, A.; Palumbo, R.; Marchetti, D.; Ceccato, I.; La Malva, P.; Maiella, R.; Cipi, M.; Roma, P.; Mammarella, N.; Verrocchio, M.C.; et al. Individual Differences, Economic Stability, and Fear of Contagion as Risk Factors for PTSD Symptoms in the COVID-19 Emergency. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 567367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orme, W.; Bowersox, L.; Vanwoerden, S.; Fonagy, P.; Sharp, C. The relation between epistemic trust and borderline pathology in an adolescent inpatient sample. Borderline Pers. Disord. Emot. Dysregulation 2019, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonagy, P.; Luyten, P.; Allison, E. Epistemic Petrification and the Restoration of Epistemic Trust: A New Conceptualization of Borderline Personality Disorder and Its Psychosocial Treatment. J. Pers. Disord. 2015, 29, 575–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, J.L.; Bos, W.V.D.; Roeber, B.J.; Rudolph, K.D.; Davidson, R.J.; Pollak, S.D. Early adversity and learning: Implications for typical and atypical behavioral development. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2017, 58, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagli, R.J. Fear and anxiety-coping strategies during COVID-19 pandemic in lockdown. J. Int. Oral Health 2020, 12, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şimşir, Z.; Koç, H.; Seki, T.; Griffiths, M.D. The relationship between fear of COVID-19 and mental health problems: A meta-analysis. Death Stud. 2022, 46, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huremović, D. (Ed.) Psychiatry of Pandemics: A Mental Health Response to Infection Outbreak; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddig, D.; Maskileyson, D.; Davidov, E.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. Correlates of COVID-19 vaccination intentions: Attitudes, institutional trust, fear, conspiracy beliefs, and vaccine skepticism. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 302, 114981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurist, E. Minding Emotions: Cultivating Mentalization in Psychotherapy; Guilford Publications: Guilford, NC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Safiye, T.; Gutić, M.; Milidrag, A.; Zlatanović, M.; Radmanović, B. The Impact of COVID-19 on Mental Health: The Protective Role of Resilience and Capacity for Mentalizing. In Mental Health-Preventive Strategies [Working Title]; Marques, A., de Matos, M.G., Sarmento, H., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Participants (n = 333) | |

|---|---|---|

| M ± ds (min-max) | ||

| Age | 31.71 ± 11.14 (18-71) Q3–Q1: 22–40 | |

| n (%) | ||

| Sex assign at birth | Female | 217 (65.17) |

| Male | 116 (34.83) | |

| Gender | Female | 212 (63.66) |

| Male | 110 (33.03) | |

| Transgender | 1 (0.3) | |

| Non-binary spectrum | 4 (1.2) | |

| Currently exploring gender identity | 6 (1.8) | |

| Sexual Orientation | Heterosexual | 237 (71.17) |

| Bisexual | 31 (9.31) | |

| Homosexual | 50 (15.02) | |

| Pansexual | 11 (3.3) | |

| Asexual | 4 (1.2) | |

| Marital Status | Unmarried | 269 (80.78) |

| Married | 53 (15.92) | |

| Separated | 10 (3) | |

| Widowed | 1 (0.3) | |

| Relational Status | Single | 162 (48.65) |

| Couple | 160 (48.05) | |

| Polyamory | 11 (3.3) | |

| Education Level | Middle School | 16 (4.8) |

| High School | 140 (42.04) | |

| University | 131 (39.34) | |

| PhD and Postgrads courses | 46 (13.81) | |

| Work Status | Unemployed | 32 (9.61) |

| Employed | 179 (53.75) | |

| Student | 120 (36.04) | |

| Retired | 2 (0.6) |

| Variables | Participants (n = 333) | |

|---|---|---|

| M ± ds (min-max) | ||

| Monkeypox knowledge | 3.04 ± 1.1 (0–5) Q3–Q1: 2–4 | |

| Fear about Monkeypox (Total Score) | 3.54 ± 2.42 (0–15) Q3–Q1: 2–5 | |

| n (%) | ||

| Where did you mainly acquire your knowledge about monkeypox? | From the news and newspapers | 109 (32.73) |

| From social media | 80 (24.02) | |

| From friends, relatives, and colleagues | 18 (5.41) | |

| I have searched info on internet | 86 (25.83) | |

| Books and other scientific fonts | 20 (6.01) | |

| I have not received any information about monkeypox | 20 (6.01) | |

| How scared do you feel about monkeypox? | Not at all | 82 (24.62) |

| Little | 141 (42.34) | |

| Moderately | 75 (22.52) | |

| Quite | 25 (7.51) | |

| Very | 6 (1.8) | |

| Very much | 4 (1.2) | |

| How much do you feel at risk of contracting monkeypox? | Not at all | 92 (27.63) |

| Little | 164 (49.25) | |

| Moderately | 61 (18.31) | |

| Quite | 9 (2.7) | |

| Very | 3 (0.9) | |

| Very much | 4 (1.2) | |

| How far do you think monkeypox could spread so far as to become a pandemic (as happened with COVID-19)? | Not at all | 70 (21.02) |

| Little | 151 (45.35) | |

| Moderately | 80 (24.02) | |

| Quite | 20 (6.01) | |

| Very | 7 (2.1) | |

| Very much | 5 (1.5) | |

| How much do you think monkeypox is a hoax or fake news? | Not at all | 206 (61.86) |

| Little | 75 (22.52) | |

| Moderately | 23 (6.91) | |

| Quite | 10 (3) | |

| Very | 7 (2.1) | |

| Very much | 12 (3.6) | |

| How much do you think the media are amplifying or exaggerating the danger of monkeypox? | Not at all | 39 (11.71) |

| Little | 68 (20.42) | |

| Moderately | 91 (27.33) | |

| Quite | 72 (21.62) | |

| Very | 28 (8.4) | |

| Very much | 35 (10.51) | |

| Number of times COVID-19 has been contracted | Never | 151 (45.34) |

| Once | 158 (47.45) | |

| Twice | 24 (7.21) | |

| Number of doses of anti-COVID-19 vaccine administered | Zero | 34 (10.21) |

| One | 2 (0.6) | |

| Two | 46 (13.81) | |

| Three | 247 (74.17) | |

| Four | 4 (1.2) | |

| How much do you feel in agreement with the NO-VAX positions expressed during the COVID-19 pandemic? | Totally agree | 53 (15.92) |

| Partially agree | 36 (10.81) | |

| Neither in agreement nor disagreement | 25 (7.51) | |

| Partially disagree | 30 (9.01) | |

| Totally disagree | 189 (56.76) |

| 1.1 Demographics such as age, gender, sexual orientation, and relationship status (R2 = 0.045; F = 2.973; p = 0.012) | |||

| B | SE | β | |

| Age | −0.016 | 0.013 | −0.073 |

| Gender (Female = 0/Male = 1) | −0.269 | 0.328 | −0.052 |

| Sexual orientation (Heterosexual = 0/LGB+ = 1) | 0.772 | 0.326 | 0.141 * |

| Being in a relationship (No = 0/Yes = 1) | −0.628 | 0.243 | −0.144 ** |

| 1.2 Socioeconomic variables (R2 = 0.022; F = 1.825; p = 0.124) | |||

| B | SE | β | |

| Education level | −0.367 | 0.175 | −0.120 * |

| Socioeconomic status | −0.137 | 0.161 | −0.048 |

| Residence area (From metropolis to rural area) | −0.160 | 0.112 | −0.081 |

| 1.3 Political and religious orientation (R2 = 0.069; F = 4.522; p = 0.002) | |||

| B | SE | β | |

| Political Conservativisms (Right winged) | −0.192 | 0.146 | −0.085 |

| Religious Education | 0.134 | 0.142 | 0.060 |

| Religiousness | 0.507 | 0.135 | 0.247 *** |

| 2.1 Monkeypox attitudes (R2 = 0.044; F = 3.773; p = 0.005) | |||

| B | SE | β | |

| Monkeypox knowledge | 0.013 | 0.122 | 0.006 |

| Fake news | 0.065 | 0.135 | 0.033 |

| Media amplification | −0.371 | 0.108 | −0.223 *** |

| 2.2 COVID-19 QoL and attitudes (R2 = 0.109; F = 6.011; p = 0.000) | |||

| B | SE | β | |

| Current perceived QoL | −0.093 | 0.036 | −0.154 ** |

| Worsening QoL attributed to COVID-19 pandemic | 0.067 | 0.029 | 0.134 * |

| Had COVID-19 (no/yes) | 0.100 | 0.219 | 0.026 |

| Number of COVID-19 vaccine doses made | 0.571 | 0.150 | 0.236 *** |

| Agreement with No-Vax positions | 0.076 | 0.092 | 0.051 |

| 3.1 Epistemic trust (R2 = 0.105; F = 9.661; p = 0.000) | |||

| B | SE | β | |

| Trust | 0.039 | 0.025 | 0.091 |

| Mistrust | 0.019 | 0.021 | 0.054 |

| Credulity | 0.163 | 0.040 | 0.257 *** |

| 3.2 Need for closure (R2 = 0.041; F = 2.327; p = 0.033) | |||

| B | SE | β | |

| Order | 0.064 | 0.122 | 0.036 |

| Predictability | −0.143 | 0.152 | −0.075 |

| Decisiveness | 0.089 | 0.144 | 0.044 |

| Ambiguity | −0.134 | 0.172 | −0.064 |

| Close-mindedness | 0.518 | 0.159 | 0.225 *** |

| 3.3 Psychopathology (R2 = 0.112; F = 10.299; p = 0.000) | |||

| B | SE | β | |

| Somatization | 0.120 | 0.249 | 0.034 |

| Depression | 0.164 | 0.206 | 0.056 |

| Anxiety | 0.824 | 0.225 | 0.282 *** |

| 3.4 Mentalized Affectivity (R2 = 0.039; F = 3.367; p = 0.010) | |||

| B | SE | β | |

| Identifying | 0.010 | 0.027 | 0.021 |

| Processing | −0.087 | 0.028 | −0.183 ** |

| Expressing | 0.052 | 0.023 | 0.132 * |

| 4.1 LGBTQI+ attitudes (R2 = 0.043; F = 3.646; p = 0.006) | |||

| B | SE | β | |

| Closeness to LGBTQI+ community | 0.265 | 0.076 | 0.196 *** |

| Negative attitudes towards Gay Men | 0.082 | 0.079 | 0.121 |

| Negative attitudes towards Lesbians | 0.001 | 0.085 | 0.001 |

| 4.2 Sexual attitudes (R2 = 0.009; F = 1.527; p = 0.219) | |||

| B | SE | β | |

| Moralism | 0.025 | 0.015 | 0.09 |

| Final regression Best predictors (R2 = 0.324; F = 10.130; p = 0.000) | |||

| B | SE | β | |

| Step 1 | |||

| Social Desirability | −0.034 | 0.055 | −0.034 |

| Step 2 | |||

| Social Desirability (covariate) | 0.107 | 0.051 | 0.106 * |

| Sexual orientation (Heterosexual = 0/LGB+ = 1) | 0.362 | 0.278 | 0.068 |

| Being in a relationship (No = 0/Yes = 1) | −0.296 | 0.217 | −0.069 |

| Education level | −0.136 | 0.151 | −0.044 |

| Religiousness | 0.441 | 0.111 | 0.195 *** |

| Media amplifications | −0.315 | 0.082 | −0.190 *** |

| Current perceived QoL | −0.061 | 0.034 | −0.100 |

| Worsening QoL attributed to COVID-19 pandemic | 0.042 | 0.027 | 0.081 |

| Number of COVID-19 vaccine doses made | 0.306 | 0.130 | 0.120 * |

| Credulity | 0.126 | 0.034 | 0.198 *** |

| Close-mindedness | 0.204 | 0.112 | 0.089 |

| Anxiety | 0.572 | 0.166 | 0.196 *** |

| Processing | 0.018 | 0.028 | 0.039 |

| Expressing | 0.044 | 0.020 | 0.113 * |

| Closeness to LGBTQI+ community | 0.090 | 0.071 | 0.066 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nimbi, F.M.; Baiocco, R.; Giovanardi, G.; Tanzilli, A.; Lingiardi, V. Who Is Afraid of Monkeypox? Analysis of Psychosocial Factors Associated with the First Reactions of Fear of Monkeypox in the Italian Population. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 235. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13030235

Nimbi FM, Baiocco R, Giovanardi G, Tanzilli A, Lingiardi V. Who Is Afraid of Monkeypox? Analysis of Psychosocial Factors Associated with the First Reactions of Fear of Monkeypox in the Italian Population. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(3):235. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13030235

Chicago/Turabian StyleNimbi, Filippo Maria, Roberto Baiocco, Guido Giovanardi, Annalisa Tanzilli, and Vittorio Lingiardi. 2023. "Who Is Afraid of Monkeypox? Analysis of Psychosocial Factors Associated with the First Reactions of Fear of Monkeypox in the Italian Population" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 3: 235. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13030235

APA StyleNimbi, F. M., Baiocco, R., Giovanardi, G., Tanzilli, A., & Lingiardi, V. (2023). Who Is Afraid of Monkeypox? Analysis of Psychosocial Factors Associated with the First Reactions of Fear of Monkeypox in the Italian Population. Behavioral Sciences, 13(3), 235. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13030235