Cultural Distance, Classroom Silence and Culturally Responsive and Inclusive Education: Evidences from Migrant College Students in Shanghai

Abstract

1. Introduction

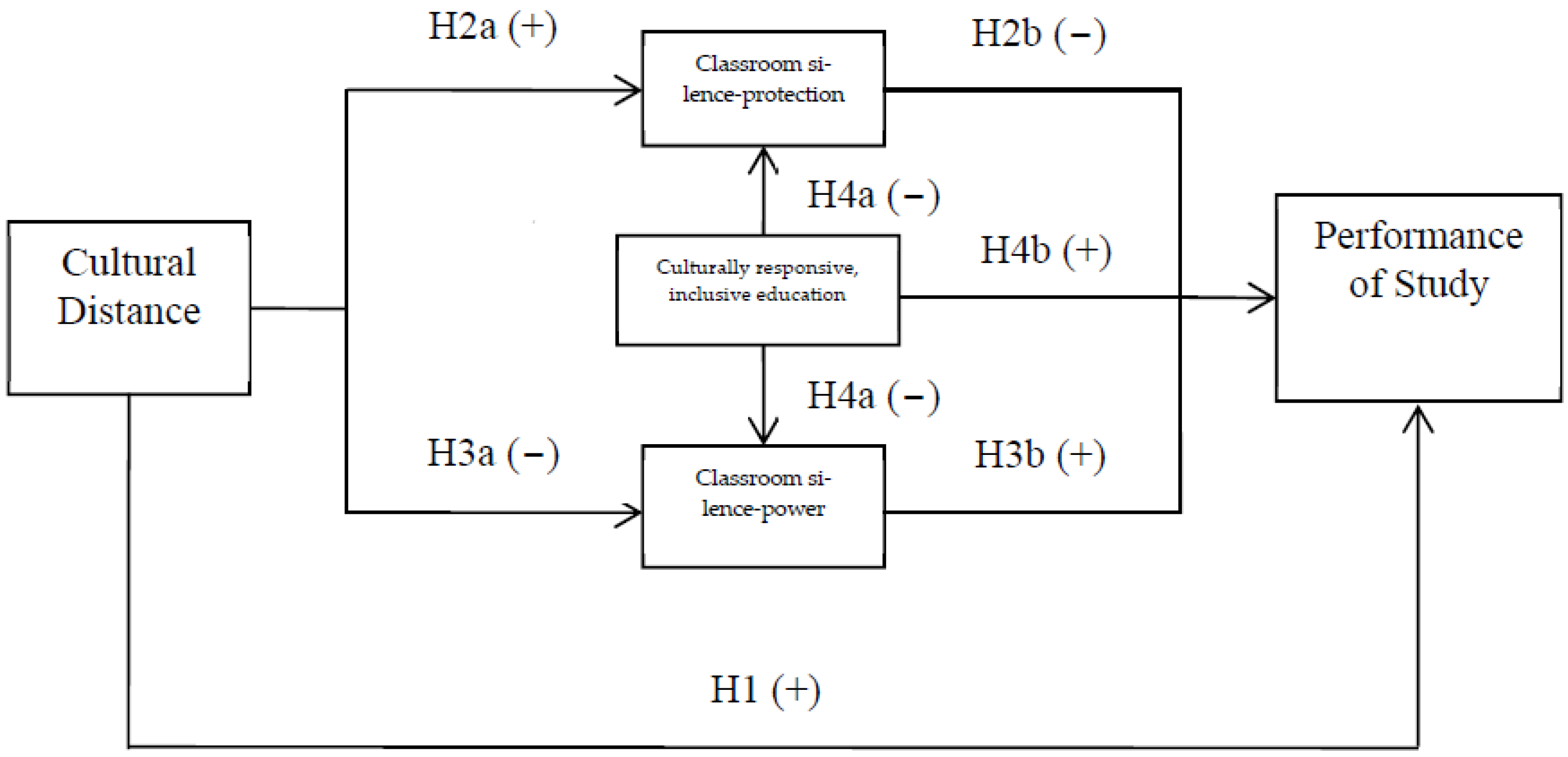

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Culture Distance and Migrant Students

2.2. Classroom Silence

2.3. Culturally Responsive and Inclusive Education

2.4. Methodology

3. Empirical Model and Data

3.1. Empirical Model

3.2. Data Description

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

3.2.2. Main Explanatory Variables

3.2.3. Control Variables

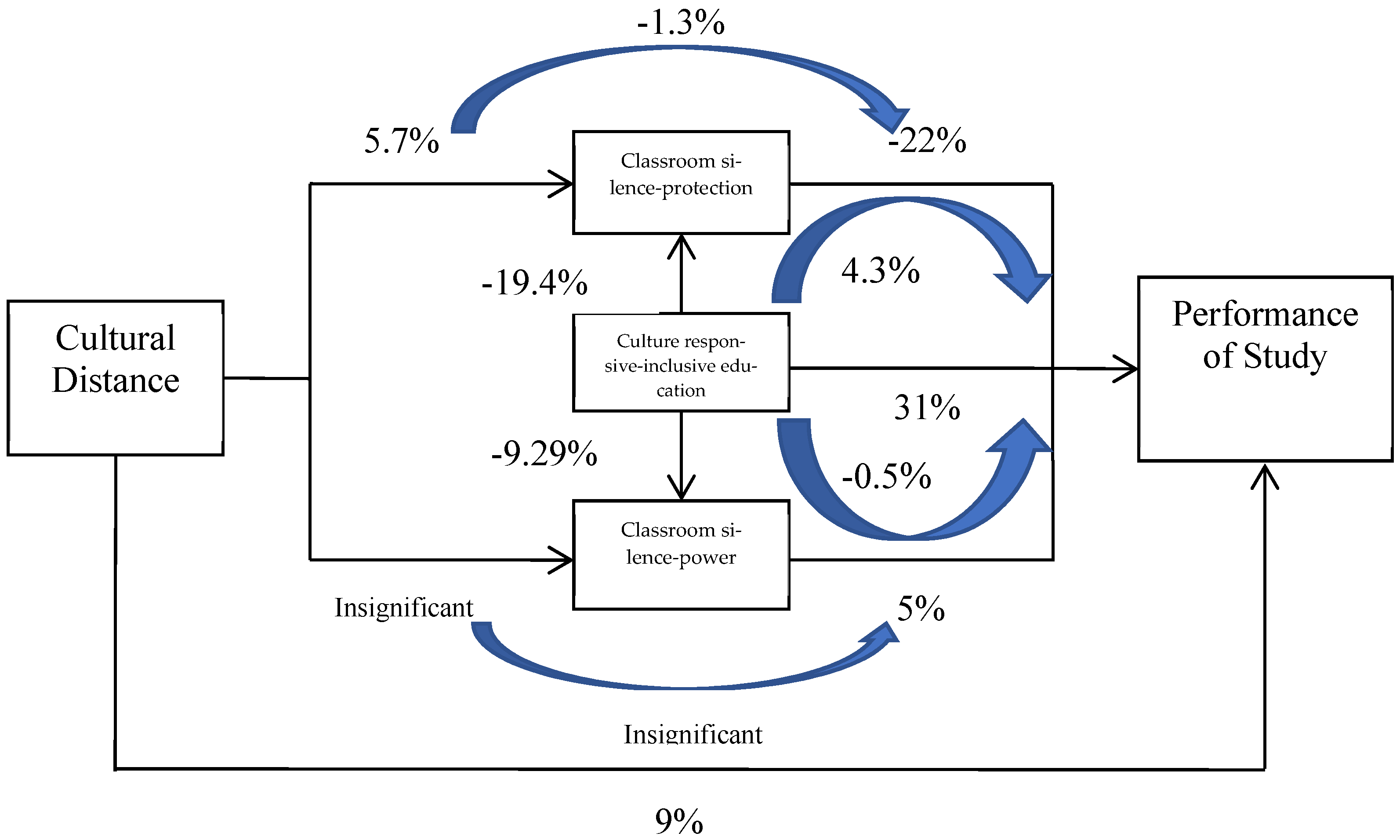

4. Empirical Results and Discussion

4.1. Study Performance

4.2. Classroom Silence

5. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gilmore, P. Silence and sulking: Emotional displays in the classroom. In Perspectives on Silence; Tannen, D., Saville-Troike, M., Eds.; Ablex: Norwood, NJ, USA, 1985; pp. 139–162. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, K. Listening: A Framework for Teaching across Difference; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, K. Interrogating students’ silences. In Everyday Antiracism: Concrete Ways to Successfully Navigate the Relevance of Race in School; Pollock, M., Ed.; New Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 217–221. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, K. Rethinking Classroom Silence: Listening to Silent Voices; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, K. After the Blackbird Whistles: Listening to Silence in Classrooms. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2010, 112, 2833–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.L. Rethinking silencing silences. In Democratic Dialogue in Education: Troubling Speech, Disturbing Silence; Boler, M., Ed.; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 69–86. [Google Scholar]

- Zembylas, M.; Michaelides, P. The sound of silence in pedagogy. Educ. Theory 2004, 54, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosacki, S.L. The Culture of Classroom Silence; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Granger, C.A. Silence in Second Language Learning: A Psychoanalytic Reading; Multilingual Matters: Clevedon, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Solberg, V.S.H.; Lillis, J.; Zhang, W.; Martin, J.L. Career Development Policy Strategies for Supporting Transition of Students with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities. In Careers for Students with Special Educational Needs; Yuen, M., Beamish, W., Solberg, V., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Philips, S.U. The Invisible Culture: Communication in Classroom and Community on the Warm Springs Indian Reservation; Longman: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, J. Approaches to multicultural curriculum reform. Trotter Rev. 1989, 3, 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, M. Framing Dropouts: Notes on the Politics of an Urban High School; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Cerna, L.; Brussino, O.; Mezzanotte, C. The Resilience of Students with an Immigrant Background: An Update with PISA 2021; OECD Education Working Papers No. 261; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amsler, S.; Kerr, J.; Andreotti, V. Interculturality in teacher education in times of unprecedented global challenges. Educ. Soc. 2020, 38, 13–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H. Educating culturally responsive Han teachers: Case study of a teacher education program in China. Int. J. Multicult. Educ. 2018, 20, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Sude Wang, T.; Zhang, W.; Chen, N.; Simpson, A.; Dervin, F. Chinese Minzu education in higher education: An inspiration for ‘Western’ diversity education? Br. J. Educ. Stud. 2020, 68, 461–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dervin, F.; Yuan, M. Revitalizing Interculturality in Education: Chinese Minzu as a Companion; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Çolak, F.Z.; Agirdag, O. Characteristics, issues, and future directions in Chinese multicultural education: A review of selected research 2000–2018. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2020, 21, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harumi, S. Classroom silence: Voices from Japanese EFL learners. ELT J. 2010, 65, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saylag, R. An exploration on the silence in the classroom within a diagnostic perspective: Whose silence is this? Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 114, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, D. Understanding Silence and Reticence: Ways of Participating in Second Language Acquisition; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Shanghai Municipal Statistics Bureau. Shanghai Statistical Yearbook 2021. 2021. Available online: https://tjj.sh.gov.cn/tjnj/tjnj2021.htm (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Chen, Y.; Fengy, S. The education of migrant children in China’s urban public elementary schools: Evidence from Shanghai. China Econ. Rev. 2019, 54, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, S.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, X.; Hou, L. Do peer effects influence the academic performance of rural students at private migrant schools in China? China Econ. Rev. 2019, 54, 418–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Tong, Y.; Sun, S.B. The effects of peer parental education on student achievement in urban China: The disparities between migrants and locals. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2021, 58, 675–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.M.; Kraus, A.D.; Dai, Y.; Fantry, C.; Block, T.; Kelder, B.; Howard, K.A.S.; Solberg, V.S.H. Empowering Women in Finance through Developing Girls’ Financial Literacy Skills in the United States. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juma, O.; Husiyin, M.; Akhat, A.; Habibulla, I. Students’ Classroom Silence and Hopelessness: The Impact of Teachers’ Immediacy on Mainstream Education. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 819821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, G. Preparing for Culturally Responsive Teaching. J. Teach. Educ. 2002, 53, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, G. Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Samuels, A.J. Exploring Culturally Responsive Pedagogy: Teachers’ Perspectives on Fostering Equitable and Inclusive Classrooms. SRATE J. 2018, 27, 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Orozco, C.; Strom, A.; Larios, R.A. A Culturally Responsive Guide to Fostering the Inclusion of Immigrant-Origin Students. 2018. Available online: https://reimaginingmigration.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Final_Inclusive_CS0-Curriculum_V7_8_9_2018-4.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Hu, J. Toward the Role of EFL/ESL Students’ Silence as a Facilitative Element in Their Success. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 737123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, D.H. Agricultural Development in China, 1368–1968; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, UK; Aldine Publishing Company: Chicago, IL, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Talhelm, T.; Zhang, X.; Oishi, S.; Shimin, C.; Duan, D.; Lan, X.; Kitayama, S. Large-Scale Psychological Differences within China Explained by Rice versus Wheat Agriculture. Science 2014, 344, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talhelm, T.; Zhang, X.; Oishi, S. Moving chairs in Starbucks: Observational studies find rice-wheat cultural differences in daily life in China. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaap8469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talhelm, T. Emerging evidence of cultural differences linked to rice versus wheat agriculture. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 32, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Anwar, S.; Peng, F. Cultural heterogeneity, acquisition experience and the performance of Chinese cross-border acquisitions. J. Asia Pac. Econ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, P.; Gu, Q.; Yu, X. Collectivist cultures and the emergence of family firms. J. Law Econ. 2022, 65, S293–S325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Johnson, S. Unbundling Institutions. J. Political Econ. 2005, 113, 949–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabellini, G. Culture and Institutions: Economic Development in the Regions of Europe. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2010, 8, 677–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, K.H.; Mason, J.M. Social organizational factors in learning of read: The balance of rights hypothesis. Read. Res. Q. 1981, 17, 115–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, F.; Mohatt, G. Cultural organization of participation structures in two classrooms of Indian students. In Doing the Ethnography of Schooling; Spindler, G., Ed.; Holt, Rinehart and Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1982; pp. 132–174. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama, F. Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Guiso, L.; Sapienza, P.; Zingales, L. Does culture affect economic outcomes? J. Econ. Perspect. 2006, 20, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, S.J.; Kang, T.; Yoo, Y.K. National Culture and International Differences in the Cost of Equity Capital. Manag. Int. Rev. 2013, 53, 899–916. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, D.; Kudoh, T.; Takeuchi, S. Changing Patterns of Individualism and Collectivism in the United States and Japan. Cult. Psychol. 1996, 2, 77–107. [Google Scholar]

- Stroope, S. Education and religion: Individual, congregational, and cross-level interaction effects on biblical literalism. Soc. Sci. Res. 2011, 40, 1478–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, I.; Trommsdorff, G. The Role of Culture in Social Development Over the Lifespan: An Interpersonal Relations Approach. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2014, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W. Modern Notions of Civilization and Culture in China; Palgrave MacMillan: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Birkeland, Å. Cross cultural comparative education—Fortifying preconceptions or transformation of knowledge? Policy Futures Educ. 2016, 14, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Dervin, F. Conclusion: Comparing Chinese and Nordic education systems—Some advice. In Nordic-Chinese Intersections within Education; Liu, H., Dervin, F., Du, X., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 293–300. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, V. The Year 1000: When Globalization Began; Scribner: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, A.; Krahn, H. Living Through our Children: Exploring the Education and Career ‘Choices’ of Racialized Immigrant Youth in Canada. J. Youth Stud. 2013, 16, 1000–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Müller, L. Resources, norms, and dropout intentions of migrant students in Germany: The role of social networks and social capital. Stud. High. Educ. 2022, v47, 1666–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clothey, R.; Hu, D.Y. The impact of a national goal driven higher education policy on an ethnic minority serving institution in China. High. Educ. Policy 2014, 28, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zeng, Y.; Shenkar, O. Agricultural Roots and Subnational Cultural Heterogeneity in Domestic Acquisitions. Strategy Sci. 2021, 6, 141–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, H.T. Rural China; Shanghai People’s Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, J.C.H.; Liu, T.J. The Growth and Decline of Chinese Family Clans. J. Interdiscip. Hist. 1982, 12, 375–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.D. Basic Economic Zones in Chinese History; The Commercial Press: Shanghai, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann, J. Reflections on Place and Place-Making in the Cities of China. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2007, 31, 257–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greif, A.; Tabellini, G. Cultural and institutional bifurcation: China and Europe compared. Am. Econ. Rev. 2010, 100, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J. Study on agricultural labor market in the North China Plain area in modern times. Res. Chin. Econ. Hist. 1998, 4, 76–83. [Google Scholar]

- Greif, A. Commitment, Coercion, and Markets: The Nature and Dynamics of Institutions Supporting Exchange. In Handbook of New Institutional Economics; Menard, C., Shirley, M.M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 727–786. [Google Scholar]

- Greif, A. Institutions and the Path to the Modern Economy: Lessons from Medieval Trade; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mantiri, O. The Influence of Culture on Learning Styles. Asia-Pacific International University. Saraburi. 2013. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2566117 (accessed on 8 November 2021).

- Kao, G.; Tienda, M. Optimism and Achievement: The Educational Performance of Immigrant Youth. Soc. Sci. Q. 1995, 76, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaut, R.G. Assimilation and Its Discontents: Between Rhetoric and Reality. Int. Migr. Rev. 1997, 31, 923–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yosso, T.J. Whose Culture has Capital? A Critical Race Theory Discussion of Community Cultural Wealth. Race Ethn. Educ. 2005, 8, 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gofen, A. Family Capital: How First Generation Higher Education Students Break the Intergenerational. Cycle. Fam. Relat. 2009, 58, 104–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, M. Assimilation in American Life; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton-Salazar, R.D.; Dornbusch, S.M. Social Capital and the Reproduction of Inequality: Information Networks among Mexican-Origin High School Students. Sociol. Educ. 1995, 68, 116–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M. Segmented Assimilation: Issues, Controversies and Recent Research on the New Second Generation. Int. Migr. Rev. 1997, 31, 975–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristen, C.; Granato, N. The Educational Attainment of the Second Generation in Germany. Ethnicities 2007, 7, 343–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. The Resilience of Students with an Immigrant Background: Factors that Shape Well-being. In OECD Reviews of Migrant Education; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonsdale, C. Risk transfer and the UK private finance initiative: A theoretical analysis. Policy Politics 2005, 33, 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O. The Economic Institutions of Capitalism; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons, R. Four formal(izable) theories of the firm? J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2005, 58, 200–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harumi, S. Approaches to Interacting with Classroom Silence: The Role of Teacher Talk” in East Asian Perspectives on Silence in English Language Education; King, J., Harumi, S., Eds.; Multilingual Matter: Bristol, UK, 2020; pp. 37–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hanh, N.T. Silence is gold?: A study on students’ silence in EFL classrooms. Int. J. High. Educ. 2020, 9, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, X. The plural-unity structure of the Chinese nation (Zhonghua Minzu de duoyuan yiti geju). J. Peking Univ. Beijing Daxue Xuebao 1988, 4, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, X.; Su, H. Multicultural society and multicultural unity education. J. Res. Educ. Ethn. Minor. 1997, 8, 18–30. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, X. Multicultural integrated education” and curriculum reform of basic education]. J. Chin. Soc. Educ. 2010, 11, 51–52. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, X. Cultural diversity and integrated multicultural education. Front. Educ. China 2012, 7, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Chen, L. Creating a multicultural curriculum in Han-dominant schools. Comp. Educ. 2014, 50, 400–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, M. Colormute: Race Dilemmas in an American School; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pollock, M. Everyday Antiracism: Concrete Ways to Successfully Navigate the Relevance of Race in School; New Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, J. The effect of mobile applications’ initial loading pages on users’ mental state and behavior. Displays 2021, 68, 102007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Tong, Y.; Bai, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Quan, W.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J.; Song, Y.; Tian, J.; Dong, W. Prevalence and correlates of depression and anxiety among Chinese international students in US colleges during the Covid-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandel, T.L. Dialects. In The International Encyclopedia of Language and Social Interaction; Tracy, K., Sandel, T.L., Ilie, C., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Boston, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 351–364. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, C.; van Heuven, V.J. Mutual intelligibility and similarity of Chinese dialects: Predicting judgments from objective measures. Linguist. Neth. 2007, 24, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Croucher, S.M. An exploration of organization dissent and workplace freedom of speech among young professional intra-urban migrants in Shanghai. J. Int. Intercult. Commun. 2017, 10, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaganti, R.; Sambharya, R. Strategic orientation and characteristics of upper management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1987, 8, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, H.A.; Miller, A.; Judge, W.Q. Diversification and top management team complementarity. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stata Corp. Statistical Software: Release 17; Stata Corp LP: College Station, TX, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Maher, K.; King, J. Observing anxiety in the foreign language classroom: Student silence and nonverbal cues. J. Psychol. Lang. Learn. 2020, 2, 116–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Description | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | |||||

| SP | My learning gains (knowledge, ability, accomplishment, etc.) are rich | 2.23 | 0.77 | 1 | 5 |

| CSP1 | Factor, higher value = high classroom silence (protection) | 0.00 | 2.00 | −4.84 | 4.76 |

| snervous | I feel nervous and anxious to speak in class | 2.72 | 1.31 | 1 | 5 |

| scorner | I tend to sit in the back row or in the corner during class, not wanting to speak | 3.10 | 1.34 | 1 | 5 |

| sshy | Speaking in public makes me feel embarrassed in class | 2.86 | 1.28 | 1 | 5 |

| sstupid | I would give up asking questions because I was worried that I was stupid | 2.89 | 1.32 | 1 | 5 |

| CSP2 | Factor, higher value = high classroom silence (power) | 0.00 | 2.00 | −6.32 | 6.07 |

| stshame | If I question the teacher’s point of view, it will affect the teacher’s authority | 3.58 | 1.12 | 1 | 5 |

| sostentious | If I speak a lot, it makes people think that I am a pushy person | 3.15 | 1.31 | 1 | 5 |

| ssshame | In class, questioning classmates’ perspectives can make classmates embarrassed | 3.14 | 1.18 | 1 | 5 |

| ssilence | In class, I believe that “silence is golden” | 3.46 | 1.17 | 1 | 5 |

| Main explanatory variables | |||||

| CD | Cultural distance = |rice%student − rice%Shanghai (79%)| | 0.30 | 0.27 | 0.00 | 0.79 |

| CRIE | Factor, higher value = more culturally responsive, inclusive teaching | 0.00 | 2.00 | −3.47 | 6.28 |

| tinter | Teachers use interactive teaching methods to encourage students to express their views | 2.25 | 1.05 | 1 | 5 |

| tcommu | Teachers actively communicate with students, understanding students’ opinions and providing feedback | 2.47 | 1.10 | 1 | 5 |

| tencou | Teachers show tolerance and provide encouragement if students fail to answer | 1.96 | 0.95 | 1 | 5 |

| theur | Teachers are heuristic and can make it attractive for students to participate in an interaction | 2.48 | 1.07 | 1 | 5 |

| stcharm | Teachers are knowledgeable, charming, and willing to participate in class discussion | 1.82 | 1.01 | 1 | 5 |

| Control dummy variables | |||||

| Gender | 1 = female; 0 = male | 0.68 | 0.47 | 0 | 1 |

| g1 | Freshman | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0 | 1 |

| g2 | Sophomore | 0.27 | 0.44 | 0 | 1 |

| g3 | Junior | 0.32 | 0.47 | 0 | 1 |

| g4 | Senior | 0.36 | 0.48 | 0 | 1 |

| s1 | Economics | 0.17 | 0.38 | 0 | 1 |

| s2 | Management | 0.22 | 0.41 | 0 | 1 |

| s3 | Law | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0 | 1 |

| s4 | Literature | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0 | 1 |

| s5 | Science and mathematics | 0.11 | 0.31 | 0 | 1 |

| s6 | Technology and engineering | 0.19 | 0.39 | 0 | 1 |

| s7 | Medical science | 0.07 | 0.26 | 0 | 1 |

| s8 | Art | 0.05 | 0.21 | 0 | 1 |

| s9 | Others (philosophy, education, history, agriculture, military science) | 0.07 | 0.25 | 0 | 1 |

| Dependent Variable: Study Performance (SP) | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural distance | 0.248 *** | 0.210 ** | 0.246 *** | 0.245 *** | 0.162 ** |

| (0.087) | (0.088) | (0.086) | (0.086) | (0.082) | |

| CSP1 | −0.084 *** | −0.085 *** | −0.062 *** | ||

| (0.012) | (0.012) | (0.011) | |||

| CSP2 | 0.019 * | 0.030 *** | |||

| (0.012) | (0.011) | ||||

| CRIE | 0.119 *** | ||||

| (0.011) | |||||

| Female | −0.026 | −0.067 | −0.075 | −0.057 | |

| (0.053) | (0.052) | (0.052) | (0.049) | ||

| Sophomore | 0.232 ** | 0.225 ** | 0.236 ** | 0.184 * | |

| (0.106) | (0.104) | (0.104) | (0.099) | ||

| Junior | 0.008 | 0.024 | 0.033 | 0.000 | |

| (0.105) | (0.102) | (0.102) | (0.097) | ||

| Senior | 0.051 | 0.019 | 0.026 | −0.054 | |

| (0.104) | (0.102) | (0.102) | (0.097) | ||

| Management | 0.107 | 0.118 | 0.117 | 0.095 | |

| (0.077) | (0.075) | (0.075) | (0.072) | ||

| Law | 0.116 | 0.102 | 0.094 | 0.073 | |

| (0.141) | (0.137) | (0.137) | (0.131) | ||

| Literature | 0.269 *** | 0.251 *** | 0.251 *** | 0.282 *** | |

| (0.095) | (0.093) | (0.093) | (0.088) | ||

| Science and mathematics | 0.108 | 0.079 | 0.077 | 0.063 | |

| (0.093) | (0.091) | (0.091) | (0.086) | ||

| Technology and engineering | 0.118 | 0.084 | 0.080 | 0.048 | |

| (0.080) | (0.079) | (0.079) | (0.075) | ||

| Medical science | −0.017 | −0.022 | −0.026 | −0.025 | |

| (0.106) | (0.103) | (0.103) | (0.098) | ||

| Art | 0.166 | 0.151 | 0.151 | 0.150 | |

| (0.123) | (0.120) | (0.120) | (0.114) | ||

| Others | 0.160 | 0.118 | 0.123 | 0.095 | |

| (0.107) | (0.104) | (0.104) | (0.099) | ||

| R-squared | 0.008 | 0.032 | 0.078 | 0.080 | 0.168 |

| N | 1051 | 1051 | 1051 | 1051 | 1051 |

| Dependent Variable: Classroom Silence (CS) | CSP1 | CSP2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Cultural distance | 0.425 * | 0.423 * | 0.540 ** | 0.071 | 0.070 | 0.126 |

| (0.227) | (0.227) | (0.224) | (0.227) | (0.230) | (0.230) | |

| Culturally responsive | −0.194 *** | −0.092 *** | ||||

| (0.030) | (0.031) | |||||

| Female | −0.481 *** | −0.500 *** | 0.430 *** | 0.422 *** | ||

| (0.136) | (0.134) | (0.138) | (0.137) | |||

| Sophomore | −0.089 | 0.009 | −0.572 ** | −0.526 * | ||

| (0.274) | (0.270) | (0.278) | (0.277) | |||

| Junior | 0.186 | 0.241 | −0.466 * | −0.440 | ||

| (0.270) | (0.265) | (0.273) | (0.272) | |||

| Senior | −0.371 | −0.220 | −0.336 | −0.264 | ||

| (0.269) | (0.265) | (0.272) | (0.272) | |||

| Management | 0.134 | 0.162 | 0.081 | 0.095 | ||

| (0.200) | (0.196) | (0.202) | (0.201) | |||

| Law | −0.175 | −0.140 | 0.381 | 0.398 | ||

| (0.363) | (0.357) | (0.368) | (0.366) | |||

| Literature | −0.212 | −0.254 | 0.007 | -0.014 | ||

| (0.246) | (0.241) | (0.249) | (0.248) | |||

| Science and mathematics | -0.344 | -0.309 | 0.082 | 0.099 | ||

| (0.240) | (0.236) | (0.243) | (0.242) | |||

| Technology and engineering | -0.406 * | -0.341 * | 0.186 | 0.217 | ||

| (0.207) | (0.204) | (0.210) | (0.209) | |||

| Medical science | −0.056 | −0.057 | 0.190 | 0.189 | ||

| (0.273) | (0.268) | (0.276) | (0.275) | |||

| Art | −0.180 | −0.172 | −0.013 | −0.009 | ||

| (0.318) | (0.312) | (0.322) | (0.321) | |||

| Others | −0.499 * | −0.429 | −0.258 | −0.225 | ||

| (0.276) | (0.271) | (0.279) | (0.278) | |||

| R-squared | 0.003 | 0.039 | 0.076 | 0.000 | 0.017 | 0.026 |

| N | 1051 | 1051 | 1051 | 1051 | 1051 | 1051 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peng, F.; Kang, L.; Shi, J.; Liu, M. Cultural Distance, Classroom Silence and Culturally Responsive and Inclusive Education: Evidences from Migrant College Students in Shanghai. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13030193

Peng F, Kang L, Shi J, Liu M. Cultural Distance, Classroom Silence and Culturally Responsive and Inclusive Education: Evidences from Migrant College Students in Shanghai. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(3):193. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13030193

Chicago/Turabian StylePeng, Fei, Lili Kang, Jinhai Shi, and Ming Liu. 2023. "Cultural Distance, Classroom Silence and Culturally Responsive and Inclusive Education: Evidences from Migrant College Students in Shanghai" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 3: 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13030193

APA StylePeng, F., Kang, L., Shi, J., & Liu, M. (2023). Cultural Distance, Classroom Silence and Culturally Responsive and Inclusive Education: Evidences from Migrant College Students in Shanghai. Behavioral Sciences, 13(3), 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13030193