Building Work Engagement in Organizations: A Longitudinal Study Combining Social Exchange and Social Identity Theories

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Relationship between Social Support and Work Engagement

2.2. The Relationship between Organizational Identification and Work Engagement

2.3. The Interaction between Social Support and Organizational Identification

3. Research Hypotheses

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Participants and Procedure

4.2. Measures

4.3. Data Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

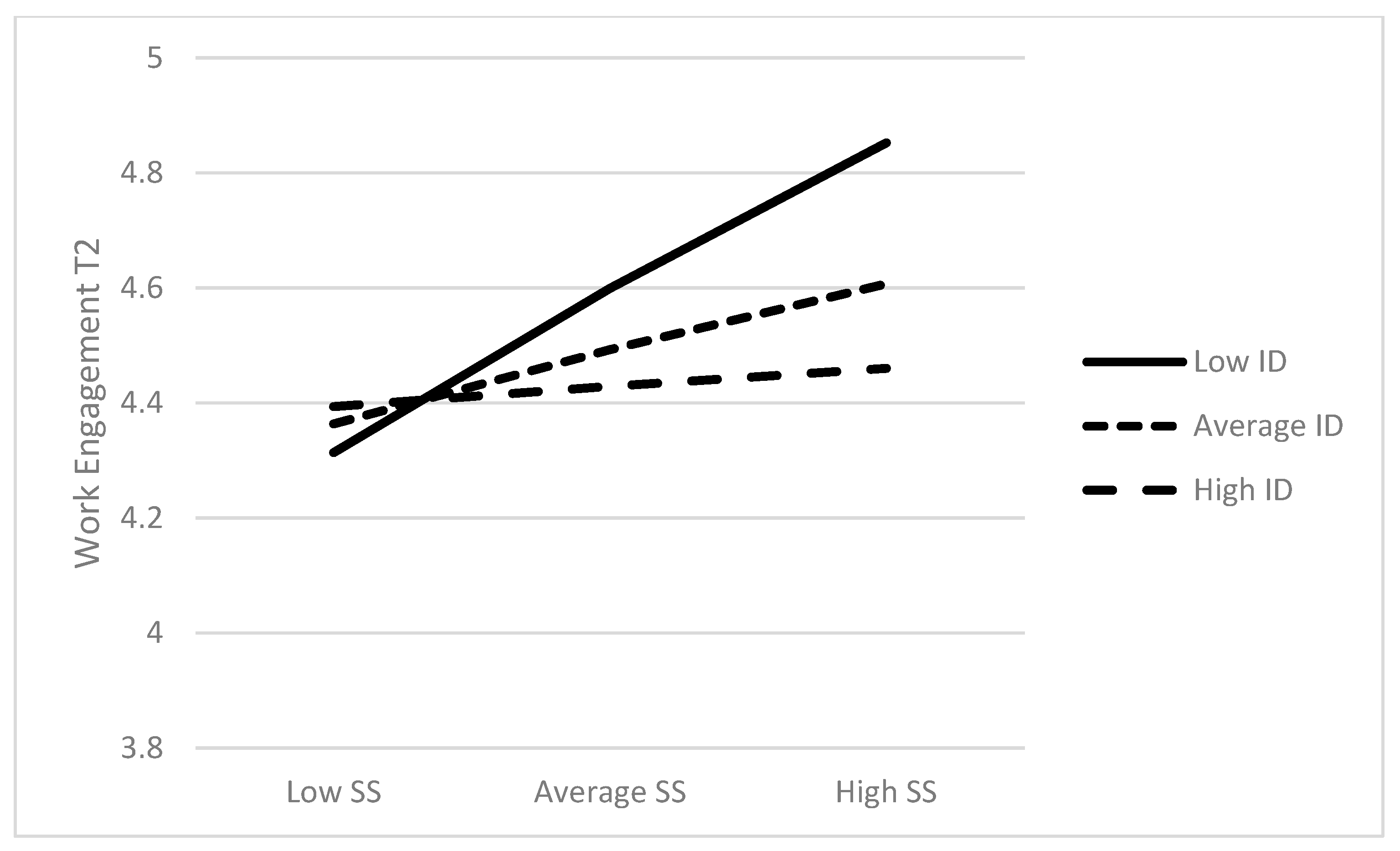

5.2. Hypothesis Testing

6. Discussion

6.1. Practical Implication

6.2. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bakker, A.B. The Peak Performing Organization; Burke, R.J., Cooper, C.L., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2008; ISBN 9780429242151. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M.E.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Positive Psychology. An Introduction. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Defining and Measuring Work Engagement: Bringing Clarity to the Concept. In Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research; Bakker, A.B., Leiter, M., Eds.; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2011; pp. 10–24. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzetti, G.; Robledo, E.; Vignoli, M.; Topa, G.; Guglielmi, D.; Schaufeli, W.B. Work Engagement: A Meta-Analysis Using the Job Demands-Resources Model. Psychol. Rep. 2021, 0, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxwell, S.E.; Cole, D.A. Bias in Cross-Sectional Analyses of Longitudinal Mediation. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-Resources Model: State of the Art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoreva, V.; van Zalk, M. Antecedents of Work Engagement among High Potential Employees. Career Dev. Int. 2016, 21, 459–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monje Amor, A.; Xanthopoulou, D.; Calvo, N.; Abeal Vázquez, J.P. Structural Empowerment, Psychological Empowerment, and Work Engagement: A Cross-Country Study. Eur. Manag. J. 2021, 39, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babcock-Roberson, M.E.; Strickland, O.J. The Relationship Between Charismatic Leadership, Work Engagement, and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors. J. Psychol. 2010, 144, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simbula, S.; Guglielmi, D.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Depolo, M. An Italian Validation of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale: Characterization of Engaged Groups in a Sample of Schoolteachers. Boll. Di Psicol. Appl. 2013, 268, 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job Demands–Resources Theory: Taking Stock and Looking Forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P.; Maslach, C. Burnout: 35 Years of Research and Practice. Career Dev. Int. 2009, 14, 204–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; van Rhenen, W. How Changes in Job Demands and Resources Predict Burnout, Work Engagement, and Sickness Absenteeism. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 893–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesener, T.; Gusy, B.; Wolter, C. The Job Demands-Resources Model: A Meta-Analytic Review of Longitudinal Studies. Work Stress 2019, 33, 76–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesener, T.; Gusy, B.; Jochmann, A.; Wolter, C. The Drivers of Work Engagement: A Meta-Analytic Review of Longitudinal Evidence. Work Stress 2020, 34, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolly, P.M.; Kong, D.T.; Kim, K.Y. Social Support at Work: An Integrative Review. J. Organ. Behav. 2021, 42, 229–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín Arribas, M.C.C. Estrés Relacionado Con El Trabajo (Modelo de Demanda-Controlapoyo Social) y Alteraciones En La Salud: Una Revisión de La Evidencia Existente. Enferm. Intensiva 2007, 18, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simbula, S.; Guglielmi, D.; Schaufeli, W.B. A Three-Wave Study of Job Resources, Self-Efficacy, and Work Engagement among Italian Schoolteachers. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2011, 20, 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisler, M.; Berthelsen, H.; Muhonen, T. Retaining Social Workers: The Role of Quality of Work and Psychosocial Safety Climate for Work Engagement, Job Satisfaction, and Organizational Commitment. Hum. Serv. Organ. Manag. Leadersh. Gov. 2019, 43, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarenhas, C.; Galvão, A.R.; Marques, C.S. How Perceived Organizational Support, Identification with Organization and Work Engagement Influence Job Satisfaction: A Gender-Based Perspective. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, K.H.; Lee, C.Y.; Peng, N.L. Burnout and Work Engagement among Dispatch Workers in Courier Service Organizations. Asia-Pac. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2021, 21, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood, N.R. Leveraging Employee Engagement for Competitive Advantage: HR’s Strategic Role. HR Mag. 2007, 52, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger, R.; Huntington, R.; Hutchison, S.; Sowa, D. Perceived Organizational Support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; ISBN 9780203792643. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, R.M. Social Exchange Theory. Annu. Rev. Sociol 1976, 2, 335–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homans, G.C. Social Behavior as Exchange. Am. J. Sociol. 1958, 63, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladebo, O.J. Perceived Supervisory Support and Organisational Citizenship Behaviours: Is Job Satisfaction a Mediator? S. Afr. J. Psychol. 2008, 38, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Min, Q.; Zhai, Q.; Smyth, R. Self-Disclosure in Chinese Micro-Blogging: A Social Exchange Theory Perspective. Inf. Manag. 2016, 53, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, R.M. Power-Dependence Relations. Sociol. Rev. 1962, 27, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, K.S.; Cheshire, C.; Rice, E.R.W.; Nakagawa, S. Social Exchange Theory. In Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 61–88. [Google Scholar]

- Ancarani, A.; di Mauro, C.; Giammanco, M.D.; Giammanco, G. Work Engagement in Public Hospitals: A Social Exchange Approach. Int. Rev. Public Adm. 2018, 23, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J. An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Austin, W.G., Worchel, S., Eds.; Brooks/Cole: Monterey, CA, USA, 1979; pp. 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Harrison, S.H.; Corley, K.G. Identification in Organizations: An Examination of Four Fundamental Questions. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 325–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social Identity Theory and the Organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avanzi, L.; Fraccaroli, F.; Castelli, L.; Marcionetti, J.; Crescentini, A.; Balducci, C.; van Dick, R. How to Mobilize Social Support against Workload and Burnout: The Role of Organizational Identification. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2018, 69, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriş, A.; Kökalan, Ö. The Moderating Effect of Organizational Identification on the Relationship Between Organizational Role Stress and Job Satisfaction. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valencia, M.N.; Regina, M.; de Gracia, L. The Moderating Role of Organizational Identification in the Relationship Between Job Demands and Burnout. J. Stress Trauma Anxiety Resil. 2022, 1, 28–39. [Google Scholar]

- van Dick, R.; Haslam, A.S. Stress and Well-Being in the Workplace: Support for Key Propositions from the Social Identity Approach. In The Social Cure: Identity, Health and Well-Being; Jetten, J., Haslam, C., Haslam, S.A., Eds.; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2012; pp. 175–194. [Google Scholar]

- Ötken, A.B.; Erben, G.S. Investigating the Relationship Between Organizational Identification and Work Engagement and the Role of Supervisor Support. Gazi Üniversitesi İktisadi Ve İdari Bilim. Fakültesi Derg. 2010, 12, 93–118. [Google Scholar]

- Fallatah, F.; Laschinger, H.K.S.; Read, E.A. The Effects of Authentic Leadership, Organizational Identification, and Occupational Coping Self-Efficacy on New Graduate Nurses’ Job Turnover Intentions in Canada. Nurs. Outlook 2017, 65, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dick, R.; Christ, O.; Stellmacher, J.; Wagner, U.; Ahlswede, O.; Grubba, C.; Hauptmeier, M.; Hohfeld, C.; Moltzen, K.; Tissington, P.A. Should I Stay or Should I Go? Explaining Turnover Intentions with Organizational Identification and Job Satisfaction*. Br. J. Manag. 2004, 15, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, D.F.; Peach, J.M.; Messervey, D.L. The Combined Effect of Ethical Leadership, Moral Identity, and Organizational Identification on Workplace Behavior. J. Leadersh. Stud. 2019, 13, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanika-Murray, M.; Duncan, N.; Pontes, H.M.; Griffiths, M.D. Organizational Identification, Work Engagement, and Job Satisfaction. J. Manag. Psychol. 2015, 30, 1019–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccoli, B.; Callea, A.; Urbini, F.; Chirumbolo, A.; Ingusci, E.; de Witte, H. Job Insecurity and Performance: The Mediating Role of Organizational Identification. Pers. Rev. 2017, 46, 1508–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avanzi, L.; Perinelli, E.; Bressan, M.; Balducci, C.; Lombardi, L.; Fraccaroli, F.; van Dick, R. The Mediational Effect of Social Support between Organizational Identification and Employees’ Health: A Three-Wave Study on the Social Cure Model. Anxiety Stress Coping 2021, 34, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.-S.S.; Park, T.-Y.Y.; Koo, B. Identifying Organizational Identification as a Basis for Attitudes and Behaviors: A Meta-Analytic Review. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 1049–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riketta, M. Organizational Identification: A Meta-Analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 2005, 66, 358–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffens, N.K.; Haslam, S.A.; Schuh, S.C.; Jetten, J.; van Dick, R. A Meta-Analytic Review of Social Identification and Health in Organizational Contexts. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 21, 303–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dick, R.; Grojean, M.W.; Christ, O.; Wieseke, J. Identity and the Extra Mile: Relationships between Organizational Identification and Organizational Citizenship Behaviour. Br. J. Manag. 2006, 17, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Knippenberg, D.; van Dick, R.; Tavares, S. Social Identity and Social Exchange: Identification, Support, and Withdrawal From the Job. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 37, 457–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesen, M. Linking Organizational Identification with Individual Creativity: Organizational Citizenship Behavior as a Mediator. J. Yaşar Univ. 2016, 11, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Brown, A.D. Organizational Identity and Organizational Identification: A Review of the Literature and Suggestions for Future Research. Group Organ. Manag. 2013, 38, 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanjanakan, P.; Zhu, D.; Doan, T.; Kim, P.B. Taking Stock: A Meta-Analysis of Work Engagement in the Hospitality and Tourism Context. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avanzi, L.; Fraccaroli, F.; Sarchielli, G.; Ullrich, J.; van Dick, R. Staying or Leaving: A Combined Social Identity and Social Exchange Approach to Predicting Employee Turnover Intentions. Int. J. Product. Perform. Management 2014, 63, 272–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, L.; Niccols, A.; Paglia, A.; Coolbear, J.; Parker, K.C.H.; Poulton, L.; Guger, S.; Sitarenios, G. A Meta-Analysis of Time between Maternal Sensitivity and Attachment Assessments: Implications for Internal Working Models in Infancy/Toddlerhood. J. Soc. Pers. Relationsh. 2016, 17, 791–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riketta, M. The Causal Relation Between Job Attitudes and Performance: A Meta-Analysis of Panel Studies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mael, F.; Ashforth, B.E. Alumni and Their Alma Mater: A Partial Test of the Reformulated Model of Organizational Identification. J. Organ. Behav. 1992, 13, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergami, M.; Bagozzi, R.P. Self-Categorization, Affective Commitment and Group Self-Esteem as Distinct Aspects of Social Identity in the Organization. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 39, 555–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Salanova, M. The Measurement of Work Engagement With a Short Questionnaire. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.A.; Webster, S.; van Laar, D.; Easton, S. Psychometric Analysis of the UK Health and Safety Executive’s Management Standards Work-Related Stress Indicator Tool. Work Stress 2008, 22, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toderi, S.; Balducci, C.; Edwards, J.A.; Sarchielli, G.; Broccoli, M.; Mancini, G. Psychometric Properties of the UK and Italian Versions of the HSE Stress Indicator Tool. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2013, 29, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, T.W.H.; Feldman, D.C. The Relationships of Age with Job Attitudes: A Meta-Analysis. Pers. Psychol. 2010, 63, 677–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Ropponen, A.; Schaufeli, W.B.; de Witte, H. Who Is Engaged at Work? J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2019, 61, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, T.E. Potential Problems in the Statistical Control of Variables in Organizational Research: A Qualitative Analysis With Recommendations. Organ. Res. Methods 2005, 8, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, F.A. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F.; Cai, L. Using Heteroskedasticity-Consistent Standard Error Estimators in OLS Regression: An Introduction and Software Implementation. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.S.; Ervin, L.H. Using Heteroscedasticity Consistent Standard Errors in the Linear Regression Model. Am. Stat. 2000, 54, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C.D.; Tomek, S.; Schumacker, R.E. Tests of Moderation Effects: Difference in Simple Slopes versus the Interaction Term. Mult. Linear Regres. Viewp. 2013, 39, 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier, P.A.; Tix, A.P.; Barron, K.E. Testing Moderator and Mediator Effects in Counseling Psychology Research. J. Couns. Psychol. 2004, 51, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toothaker, L.E.; Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 1994, 45, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roelen, C.A.M.; van Hoffen, M.F.A.; Groothoff, J.W.; de Bruin, J.; Schaufeli, W.B.; van Rhenen, W. Can the Maslach Burnout Inventory and Utrecht Work Engagement Scale Be Used to Screen for Risk of Long-Term Sickness Absence? Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2015, 88, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alessandri, G.; Borgogni, L.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Caprara, G.V.; Consiglio, C. From Positive Orientation to Job Performance: The Role of Work Engagement and Self-Efficacy Beliefs. J. Happiness Stud. 2015, 16, 767–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Albrecht, S. Work Engagement: Current Trends. Career Dev. Int. 2018, 23, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Chen, L. Relationships among Social Support, Empathy, Resilience and Work Engagement in Haemodialysis Nurses. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2019, 66, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avanzi, L.; van Dick, R.; Fraccaroli, F.; Sarchielli, G. The Downside of Organizational Identification: Relations between Identification, Workaholism and Well-Being. Work Stress 2012, 26, 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizumic, B.; Reynolds, K.J.; Turner, J.C.; Bromhead, D.; Subasic, E. The Role of the Group in Individual Functioning: School Identification and the Psychological Well-Being of Staff and Students. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 58, 171–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avanzi, L.; Savadori, L.; Fraccaroli, F.; Ciampa, V.; van Dick, R. Too-Much-of-a-Good-Thing? The Curvilinear Relation between Identification, Overcommitment, and Employee Well-Being. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 1256–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, N.M.; Nowell, B. Sense of Community, Sense of Community Responsibility, Organizational Commitment and Identification, and Public Service Motivation: A Simultaneous Test of Affective States on Employee Well-Being and Engagement in a Public Service Work Context. Public Manag. Rev. 2020, 22, 1024–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, C.; Patterson, M.; Dawson, J. Building Work Engagement: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Investigating the Effectiveness of Work Engagement Interventions. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 792–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, K. Review Article: How Can We Make Organizational Interventions Work? Employees and Line Managers as Actively Crafting Interventions. Hum. Relat. 2013, 66, 1029–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffens, N.K.; LaRue, C.J.; Haslam, C.; Walter, Z.C.; Cruwys, T.; Munt, K.A.; Haslam, S.A.; Jetten, J.; Tarrant, M. Social Identification-Building Interventions to Improve Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 2019, 15, 85–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bracht, E.M.; Monzani, L.; Boer, D.; Haslam, S.A.; Kerschreiter, R.; Lemoine, J.E.; Steffens, N.K.; Akfirat, S.A.; Avanzi, L.; Barghi, B.; et al. Innovation across Cultures: Connecting Leadership, Identification, and Creative Behavior in Organizations. Appl. Psychol. 2022, 72, 348–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dick, R.; Hirst, G.; Grojean, M.W.; Wieseke, J. Relationships between Leader and Follower Organizational Identification and Implications for Follower Attitudes and Behaviour. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2007, 80, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dick, R.; Cordes, B.L.; Lemoine, J.E.; Steffens, N.K.; Haslam, S.A.; Akfirat, S.A.; Ballada, C.J.A.; Bazarov, T.; Aruta, J.J.B.R.; Avanzi, L.; et al. Identity Leadership, Employee Burnout and the Mediating Role of Team Identification: Evidence from the Global Identity Leadership Development Project. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, M.T.; Tetrick, L.E. Relations among Occupational Hazards, Attitudes, and Safety Performance. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender (1 = female) | 0.68 | 0.47 | (-) | |||||||

| 2. Job tenure | 11.91 | 10.06 | −0.00 | (-) | ||||||

| 3. Organization 2 (bank) | 0.18 | 0.39 | 0.05 | 0.71 ** | (-) | |||||

| 4. Organization 3 (social cooperative) | 0.35 | 0.48 | 0.44 ** | −0.23 ** | −0.34 ** | (-) | ||||

| 5. Social support T1 | 3.28 | 0.57 | 0.05 | −0.21 * | −0.03 | 0.18 * | (0.87) | |||

| 6. Identification T1 | 3.64 | 0.81 | 0.22 ** | −0.09 | −0.07 | 0.28 ** | 0.32 ** | (0.69) | ||

| 7. Work engagement T1 | 4.44 | 1.30 | 0.22 ** | −0.25 ** | −0.22 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.50 ** | 0.47 ** | (0.94) | |

| 8. Work engagement T2 | 4.45 | 1.25 | 0.08 | −0.20 * | −0.20 * | 0.27 ** | 0.51 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.81 ** | (0.95) |

| Dependent Variable Work Engagement T2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor Variables | Coefficient | SE | p | LLCI | ULCI |

| Social support (SS) T1 | 0.27 | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.0056 | 0.5423 |

| Organizational identification (ID) T1 | −0.09 | 0.10 | 0.38 | −0.2921 | 0.1110 |

| SSxID | −0.28 | 0.10 | 0.01 | −0.4852 | −0.0770 |

| Control variables | |||||

| Gender (1 = female) | −0.22 | 0.17 | 0.19 | −0.561 | 0.1144 |

| Job tenure | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.95 | −0.0183 | 0.0194 |

| Organization 2 (bank) | −0.14 | 0.28 | 0.61 | −0.6987 | 0.4105 |

| Organization 3 (social cooperative) | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.26 | −0.1483 | 0.5484 |

| Work engagement T1 | 0.68 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.5368 | 0.8254 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Simbula, S.; Margheritti, S.; Avanzi, L. Building Work Engagement in Organizations: A Longitudinal Study Combining Social Exchange and Social Identity Theories. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13020083

Simbula S, Margheritti S, Avanzi L. Building Work Engagement in Organizations: A Longitudinal Study Combining Social Exchange and Social Identity Theories. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(2):83. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13020083

Chicago/Turabian StyleSimbula, Silvia, Simona Margheritti, and Lorenzo Avanzi. 2023. "Building Work Engagement in Organizations: A Longitudinal Study Combining Social Exchange and Social Identity Theories" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 2: 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13020083

APA StyleSimbula, S., Margheritti, S., & Avanzi, L. (2023). Building Work Engagement in Organizations: A Longitudinal Study Combining Social Exchange and Social Identity Theories. Behavioral Sciences, 13(2), 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13020083