Self-Monitoring Intervention for Adolescents and Adults with Autism: A Research Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Research Questions

- Thus, the purpose of this research review was to fill a gap in the current literature base by summarizing studies on technology-based self-monitoring interventions for adolescents and adults with autism.

- The research questions were as follows:

- What are the participant characteristics in the included studies?

- What are the characteristics of the technology-based self-monitoring interventions (i.e., delivery formats and types of technology) in the included studies?

- What are the primary dependent variables in the included studies?

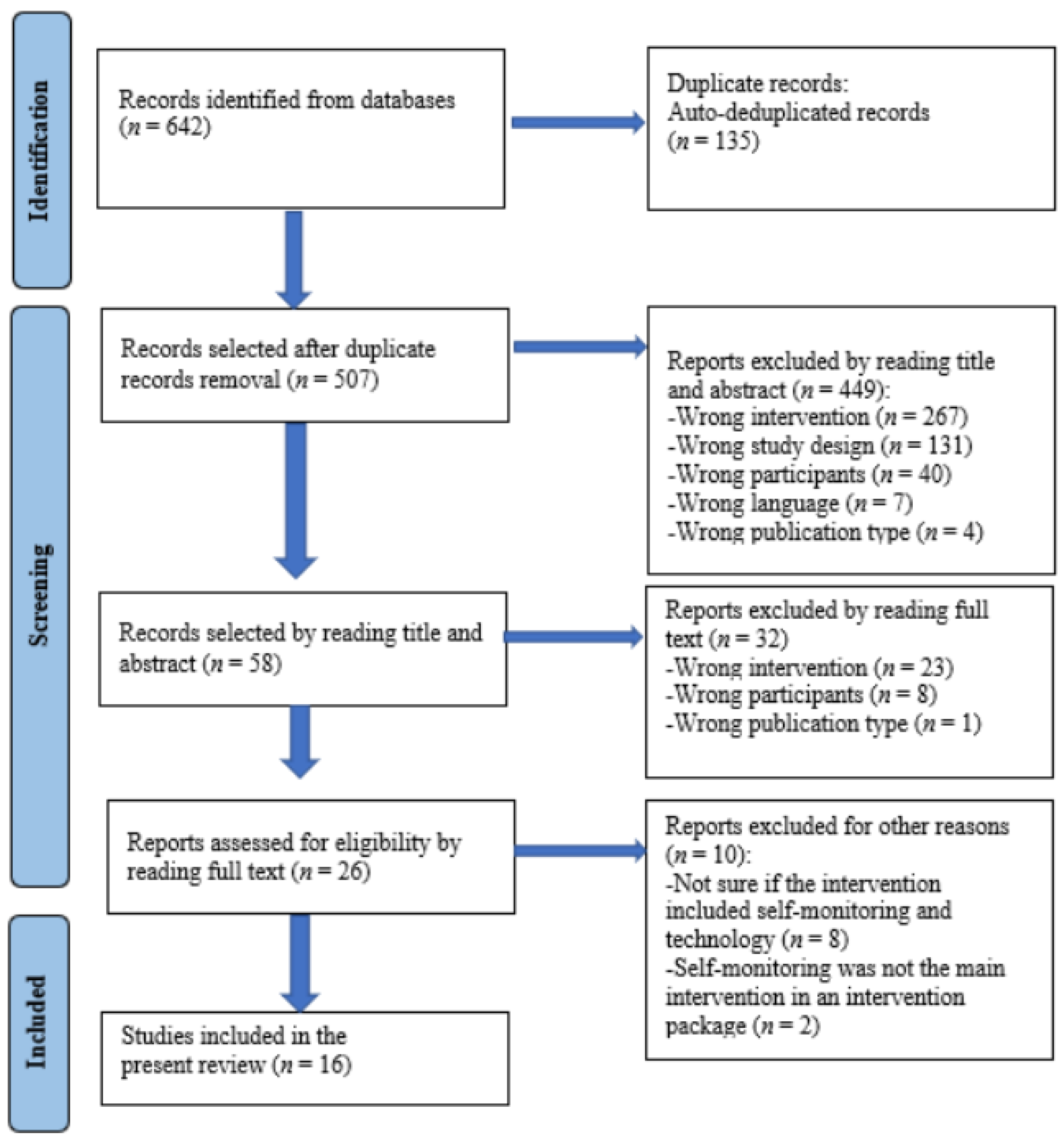

2. Method

2.1. Article Identification

2.2. Coding

2.3. Interrater Reliability

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Intervention Characteristics

3.3. Primary Dependent Variables

4. Discussion

Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hume, K.; Boyd, B.A.; Hamm, J.V.; Kucharczyk, S. Supporting Independence in Adolescents on the Autism Spectrum. Grantee Submiss. 2014, 35, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, N.; Bobzien, J. Using Two Formats of a Social Story to Increase the Verbal Initiations and On-Topic Responses of Two Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2022, 52, 4138–4149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, E.B.; Sterrett, K.; Lord, C. Work and well-being: Vocational activity trajectories in young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2021, 14, 2613–2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.R. Using a strengths-based approach to improve employment opportunities for individuals with autism spectrum disorder. New Horiz. Adult Educ. Hum. Resour. Dev. 2022, 34, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Wehman, P.; Schall, C.; Carr, S.; Targett, P.; West, M.; Cifu, G. Transition from school to adulthood for youth with autism spectrum disorder: What we know and what we need to know. J. Disabil. Policy Stud. 2014, 25, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hume, K.; Loftin, R.; Lantz, J. Increasing Independence in Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Review of Three Focused Interventions. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2009, 39, 1329–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kose, L.K.; Fox, L.; Storch, E.A. Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders and Comorbid Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Review of the Research. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2017, 30, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, T.A.; Machalicek, W. Systematic review of intervention research with adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2013, 7, 1439–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehmeyer, M.L.; Field, S. Self-Determination: Instructional and Assessment Strategies; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gilberts, G.H.; Agran, M.; Hughes, C.; Wehmeyer, M. The Effects of Peer Delivered Self-Monitoring Strategies on the Participation of Students with Severe Disabilities in General Education Classrooms. J. Assoc. Pers. Sev. Handicap. 2001, 26, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heward, W.L.; Alber, S.R.; Konrad, M. Exceptional Children: An Introduction to Special Education, Eleventh Edition; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ganz, J.B.; Sigafoos, J. Self-Monitoring: Are Young Adults with MR and Autism Able to Utilize Cognitive Strategies Independently? Educ. Train. Dev. Disabil. 2005, 40, 24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.-F.; Chen, H.; Zhang, D.; Gilson, C.B. Effects of a self-monitoring strategy to increase classroom task completion for high school students with moderate intellectual disability. Educ. Train. Autism Dev. Disabil. 2019, 54, 263–273. [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo-Montes, C.d.P.; Caurcel Cara, M.J.; Rodríguez Fuentes, A. Technologies in the education of children and teenagers with autism: Evaluation and classification of apps by work areas. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 4087–4115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbloom, R.; Wills, H.P.; Mason, R.; Huffman, J.M.; Mason, B.A. The Effects of a Technology-Based Self-monitoring Intervention on On-Task, Disruptive, and Task-Completion Behaviors for Adolescents with Autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2019, 49, 5047–5062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cañete, R.; Peralta, M.E. ASDesign: A User-Centered Method for the Design of Assistive Technology That Helps Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders Be More Independent in Their Daily Routines. Sustainability 2022, 14, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandgreen, H.; Frederiksen, L.H.; Bilenberg, N. Digital interventions for autism spectrum disorder: A meta-analysis. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2021, 51, 3138–3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odom, S.L.; Thompson, J.L.; Hedges, S.; Boyd, B.A.; Dykstra, J.R.; Duda, M.A.; Szidon, K.L.; Smith, L.E.; Bord, A. Technology-Aided Interventions and Instruction for Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Grantee Submiss. 2015, 45, 3805–3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mize, M.; Park, Y.; Carter, A. Technology-based self-monitoring system for on-task behavior of students with disabilities: A quantitative meta-analysis of single-subject research. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2022, 38, 668–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, A.; Papaioannou, D.; Sutton, A. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review; Sage: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Adolescent Health. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/adolescent-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckman, A.; Mason, B.A.; Wills, H.P.; Garrison-Kane, L.; Huffman, J. Improving Behavioral and Academic Outcomes for Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Testing an App-based Self-monitoring Intervention. Educ. Treat. Child. 2019, 42, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouck, E.C.; Savage, M.; Meyer, N.K.; Taber-Doughty, T.; Hunley, M. High-Tech or Low-Tech? Comparing Self-Monitoring Systems to Increase Task Independence for Students with Autism. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabil. 2014, 29, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cihak, D.F.; Wright, R.; Ayres, K.M. Use of Self-Modeling Static-Picture Prompts via a Handheld Computer to Facilitate Self-Monitoring in the General Education Classroom. Educ. Train. Autism Dev. Disabil. 2010, 45, 136–149. [Google Scholar]

- Clemons, L.L.; Mason, B.A.; Garrison-Kane, L.; Wills, H.P. Self-Monitoring for High School Students with Disabilities: A Cross-Categorical Investigation of I-Connect. J. Posit. Behav. Interv. 2016, 18, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crutchfield, S.; Mason, R.; Chambers, A.; Wills, H.; Mason, B. Use of a Self-monitoring Application to Reduce Stereotypic Behavior in Adolescents with Autism: A Preliminary Investigation of I-Connect. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2015, 45, 1146–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganz, J.B.; Heath, A.K.; Davis, J.L.; Vannest, K.J. Effects of a self-monitoring device on socially relevant behaviors in adolescents with Asperger disorder: A pilot study. Assist. Technol. 2013, 25, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gushanas, C.M.; Thompson, J.L. Effect of Self-Monitoring on Personal Hygiene among Individuals with Developmental Disabilities Attending Postsecondary Education. Career Dev. Transit. Except. Individ. 2019, 42, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, J.M.; Bross, L.A.; Watson, E.K.; Wills, H.P.; Mason, R.A. Preliminary investigation of a self-monitoring application for a postsecondary student with autism. Adv. Neurodev. Disord. 2019, 3, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolbenschlag, C.M.; Wunderlich, K.L. The Effects of Self-monitoring on On-task Behaviors in Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders. J. Behav. Educ. 2021, 30, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legge, D.B.; DeBar, R.M.; Alber-Morgan, S.R. The effects of self-monitoring with a MotivAider® on the on-task behavior of fifth and sixth graders with autism and other disabilities. J. Behav. Assess. Interv. Child. 2010, 1, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romans, S.K.; Wills, H.P.; Huffman, J.M.; Garrison-Kane, L. The effect of web-based self-monitoring to increase on-task behavior and academic accuracy of high school students with autism. Prev. Sch. Fail. 2020, 64, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State, T.; Kern, L. A Comparison of Video Feedback and In Vivo Self-Monitoring on the Social Interactions of an Adolescent with Asperger Syndrome. J. Behav. Educ. 2012, 21, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills, H.P.; Mason, R.; Huffman, J.M.; Heitzman-Powell, L. Implementing self-monitoring to reduce inappropriate vocalizations of an adult with autism in the workplace. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2019, 58, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, J.; Sheppard, M.; Brown, M. Brief Report: Using iPads for Self-Monitoring of Students with Autism; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 1559–1567. [Google Scholar]

- Yakubova, G.; Taber-Doughty, T. Brief Report: Learning Via the Electronic Interactive Whiteboard for Two Students with Autism and a Student with Moderate Intellectual Disability. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2013, 43, 1465–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szwedo, D.E.; Hessel, E.T.; Loeb, E.L.; Hafen, C.A.; Allen, J.P. Adolescent support seeking as a path to adult functional independence. Dev. Psychol. 2017, 53, 949–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bross, L.A.; Travers, J.C.; Munandar, V.D.; Morningstar, M. Video Modeling to Improve Customer Service Skills of an Employed Young Adult With Autism. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabil. 2019, 34, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bross, L.A.; Travers, J.C.; Wills, H.P.; Huffman, J.M.; Watson, E.K.; Morningstar, M.E.; Boyd, B.A. Effects of Video Modeling for Young Adults With Autism in Community Employment Settings. Career Dev. Transit. Except. Individ. 2020, 43, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restorff, D.E.; Abery, B.H. Observations of Academic Instruction for Students With Significant Intellectual Disability: Three States, Thirty-Nine Classrooms, One View. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2013, 34, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| First Author (Year) | Participant Gender/Age/ Disability or Medical Diagnosis (Other Than Autism) | Primary Dependent Variable | Primary Intervention | Study Design | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beckman [24] | Participant A: Male/11 years/ Fragile X syndrome. Participant B: Male/10 years. | On-task behaviors. | Self-monitoring with the I-Connect application by responding to the visual prompt at a specific time. | Single-subject ABAB withdrawal. | 1. Each student was videotaped from baseline to rate their behavior as on- or off-task for training. 2. Reinforcers were provided. |

| Bouck [25] | Participant A: Male/15 years/ functioning at the severe level of ID. Participant B: Female/15 years/ functioning at the mild level of ID. Participant C: Female/15 years/functioning at the mild level of ID. | Skill acquisition. | A comparison of high-tech and low-tech self-monitoring: 1. High-tech: An Apple iPad 2 was used to present ingredients, receipts, and the checklist. 2. Low-tech: paper/pencil-based recipes with a self-monitoring checklist. | Single-subject alternating treatment. | The intervention on iPad was more effective than the paper/pencil-based intervention. |

| Cihak [26] | Participant A: Male/11 years. Participant B: Male/11 years. Participant C: Male/13 years. | On-task behaviors. | Self-monitoring with self-modeling static-picture prompting: 1. Photos of participants self-modeling task engagement were taken. 2. Participants watched the self-modeling photo and monitored their task engagement by marking “Yes” or “No.” | Single-subject ABAB with multiple probes across settings. | All phases occurred in general education settings. Three settings (courses) were targeted for each participant. |

| Clemons [27] | Participant A: Male/17 years. | On-task behaviors. | Self-monitoring with the I-Connect application by responding to the visual prompt at a specific time. | Single-subject ABAB withdrawal. | 1. Videos were used from baseline sessions to provide training. 2. Reinforcers were provided if participants correctly recorded their behaviors. |

| Crutchfield [28] | Participant A: Male/14 years/Down syndrome/ADHD. Participant B: Male/14 years/ADHD. | Problem behaviors (stereotypic behavior). | Self-monitoring with the I-Connect application by responding to the visual prompt at a specific time. | Single-subject ABAB reversal with multiple baselines across participants. | No additional reinforcers were provided. |

| Ganz [29] | Participant A: Male/12 years/ speech–language disorder. Participant B: Male/13 years. | Socially relevant behaviors. | Three-phase self-monitoring with a MotivAider device: Phase 1: Participants used the MotivAider only, Phase 2: Participants used the MotivAider and global rating form, and Phase 3: Participants used the MotivAider and tally form to monitor their behaviors. | Not clearly reported. | Reinforcers were provided if participants met the criteria set on the form. |

| Gushanas [30] | Participant A: Male/22 years. | Distracting body odor. | Hygiene self-monitoring system: 1. Participants were instructed to use SurveyMonkey to track their daily hygiene. 2. Before participants left their dormitories, participants self-monitored their hygiene by answering a list of hygiene questions on SurveyMonkey once per day. | Single-subject multiple baselines across participants. | The researcher recruited observers to observe and collect data for each participant’s level of distracting body odor 7 days a week. |

| Huffman [31] | Participant A: Male/19 years. | On-task behaviors. | Self-monitoring with the I-Connect application by responding to the visual prompt at a specific time. |

Single-subject alternating treatment with

two phases of treatment and no treatment. | 1. A 20-min self-monitoring module was used to provide training. 2. At the beginning of the training, the participant set an academic goal of achieving an “A” in the course. |

| Kolbenschlag [32] | Participant A: Male/11 years. Participant B: Male/11 years. Both participants had IQs in the low-average range. | On-task behaviors. | Self-monitoring with a single in-ear headphone connected to an iPod: 1. The in-ear headphone and iPod were used to cue participants to record their behaviors with a sound. 2. Participants used a recording page to record their on-task and off-task behaviors. | Single-subject multiple-baseline across participants. | 1. One 20-min session was conducted to train participants to use the self-monitoring procedure. 2. Reinforcers were provided if participants correctly recorded their behaviors. 3. In the maintenance phases, participants could receive a reinforcer for a high level of on-task behaviors. |

| Legge [33] | Participant A: Male/13 years. Participant B: Male/11 years. | On-task behaviors. | Self-monitoring with a MotivAider device: 1. Participants wore the MotivAider device. The device emitted a prompt to remind participants to record their on-task behaviors. 2. During the intervention phase, the device vibrated at a fixed schedule (every 2 min). 3. During the fading phase, the device vibrated at a variable schedule (every 4–6 min). | Single-case multiple baselines across participants. | Reinforcers were provided if participants correctly presented all on-task behaviors. |

| Romans [34] | Participant A: Male/17 years/ ADHD/Mild ID. Participant B: Male/15 years/ ADHD. | On-task behaviors. | Self-monitoring with the I-Connect application by responding to the visual prompt at a specific time. | Single-subject ABAB withdrawal. | 1. Videos were used from baseline sessions to provide training. 2. Reinforcers were provided if participants correctly recorded their behaviors. |

| Rosenbloom [16] | Participant A: Male/17 years. Participant B: Male/10 years. Participant C: Male/13 years. Participant D: Male/11 years. | On-task behaviors. | Self-monitoring with the I-Connect application by responding to the visual prompt at a specific time. | Single-subject ABAB withdrawal. | 1. A 20-min self-monitoring module and behavioral skills training approaches were used to conduct training. 2. No additional reinforcers were provided. |

| State [35] | Participant A: Male/14 years. | Socially relevant behaviors. | A comparison of video feedback and in vivo self-monitoring: 1. Video feedback: The participant was asked to watch his behaviors on videotape and respond to the statement “I had appropriate interactions” with a “Yes” or a “No.” 2. In vivo feedback: The participant checked the recording sheet when the prompt on a watch vibrated during the activity session. | Single-subject reversal (ABCBC) across game partners with multiple baselines. | 1. Reinforcers were provided if the participant correctly recorded their behaviors. 2. Different partners (teachers and peers) were invited to interact with the participant in the intervention sessions. 3. In vivo self-monitoring is more effective. |

| Wills [36] | Participant A: Female/30 years. | Problem behaviors (inappropriate vocalizations). | Self-monitoring with the I-Connect application by responding to the visual prompt at a specific time. | Single-subject ABAB withdrawal. | 1. The study setting was in the participant’s workplace. 2. Videos were used from baseline sessions to provide training. 3. Goal setting was used. |

| Xin [37] | Participant A: Female/11 years. Participant B: Female/10 years. Participant C: Female/10 years. Participant D: Male/12 years. | On-task behaviors. | Self-monitoring with the Choiceworks app on an iPad: 1. Choiceworks was used to help participants complete daily routines with images or photos. 2. Participants’ behaviors and voices were videotaped and saved in Choiceworks. 3. Participants watched their self-image of on-task behaviors and listened to their recorded voices to monitor their behaviors. | Single-subject ABAB reversal. | Reinforcers were provided if participants correctly presented all on-task behaviors. |

| Yakubova [38] | Participant A: Male/16 years. Participant B: Male/19 years. | Skill acquisition and interaction with an electronic interactive Whiteboard. | Self-monitoring with an electronic interactive whiteboard: Participants were asked to self-operate on an electronic interactive whiteboard, watch video clips for each task, and monitor their performance by using an electronic checklist. | Single-subject multiple probes across participants. | 1. The daily living skills were cleaning a mirror, sink, and floor. 2. Data were collected through all three tasks in five sessions. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Y.-F.; Byrne, S.; Yan, W.; Ewoldt, K.B. Self-Monitoring Intervention for Adolescents and Adults with Autism: A Research Review. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13020138

Li Y-F, Byrne S, Yan W, Ewoldt KB. Self-Monitoring Intervention for Adolescents and Adults with Autism: A Research Review. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(2):138. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13020138

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yi-Fan, Suzanne Byrne, Wei Yan, and Kathy B. Ewoldt. 2023. "Self-Monitoring Intervention for Adolescents and Adults with Autism: A Research Review" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 2: 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13020138

APA StyleLi, Y.-F., Byrne, S., Yan, W., & Ewoldt, K. B. (2023). Self-Monitoring Intervention for Adolescents and Adults with Autism: A Research Review. Behavioral Sciences, 13(2), 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13020138